Henry Compton’s Prayer Book, and John Wright’s Bible

Including as it does the library of the British and Foreign Bible Society as well as the collection of Arthur William Young, the University Library is well-supplied with Bibles in many languages, and only slightly less well-supplied with copies of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer. We rarely feel the need to acquire further examples of either. Recently, however, we have acquired copies of both, which are of interest not as examples of widely-held texts, but for how they were used and distributed.

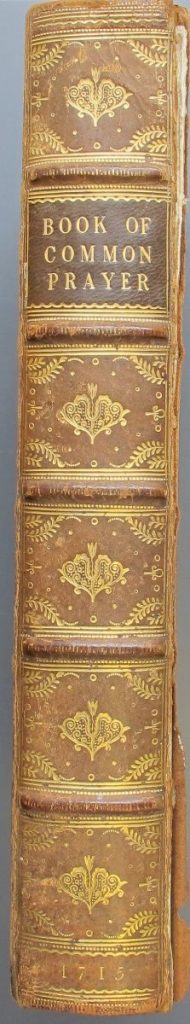

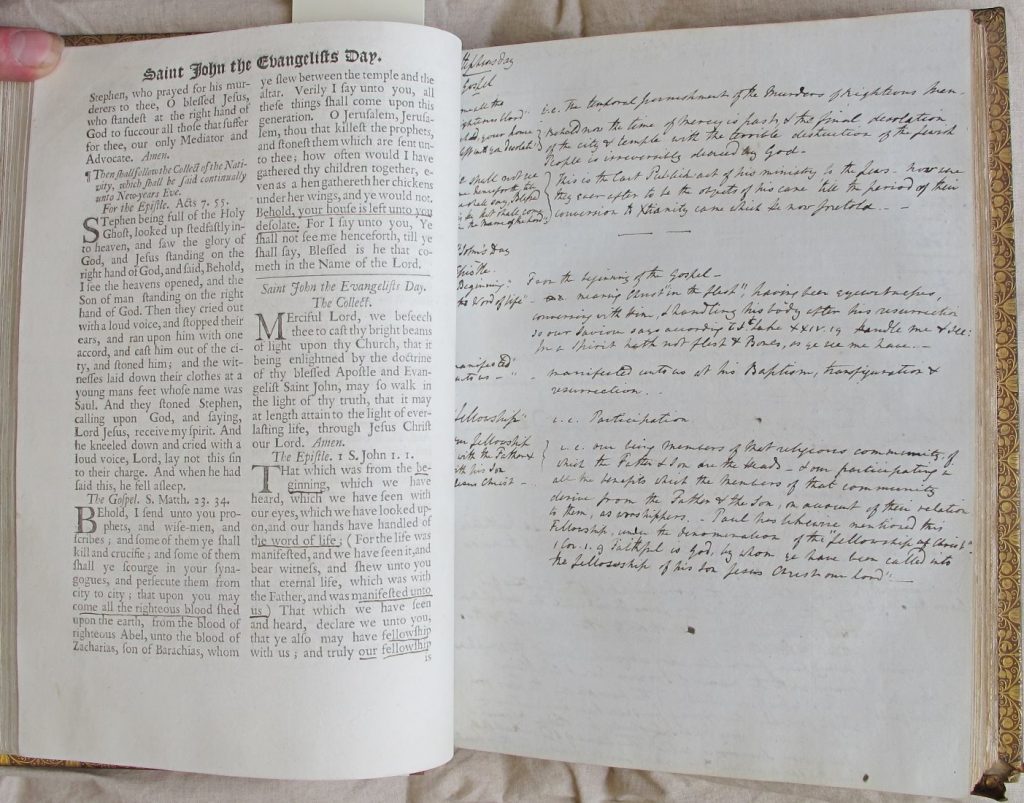

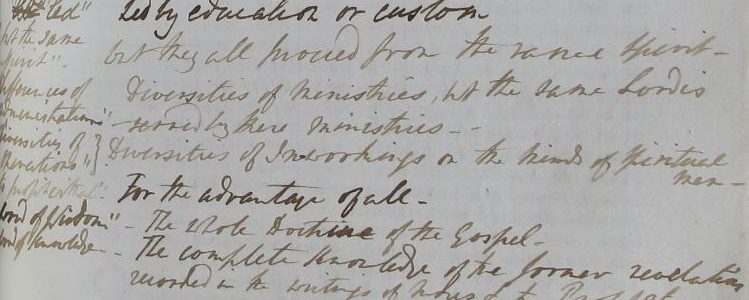

The more substantial item is a quarto prayer-book of 1715, rebound in the nineteenth century when its pages were interleaved with blank sheets of paper. The blank sheets have a watermark dated 1826 of Clarke and Horsington of Bleadney near Wells, Somerset. They bear extensive notes in ink, in a hand of the first half of the nineteenth century. The notes chiefly give detailed commentary on the Biblical texts set as readings for the various Sundays, and were perhaps intended as source material for sermons. At least some are taken from published exegetical works. For example, a note on the Gospel reading for the feast of St Stephen is taken from Joseph Benson’s critical edition of the Bible, published in 1810, and a later note on the Epistle for the feast of St John comes from James Macknight’s A New Literal Translation of All the Apostolical Epistles, first published in 1795.

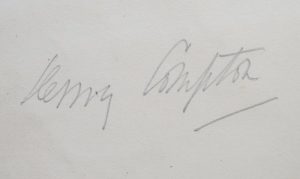

A second, apparently later, hand, writing in pencil, has also left a few notes in the early part of the book. The list of contents has six items marked with an X, and the legend “Marked with a cross to be omitted”, suggesting the book, or part of it, was used as copy for another edition. This annotator is probably the “Henry [or possibly Kerry] Compton” who signed the front free end paper.

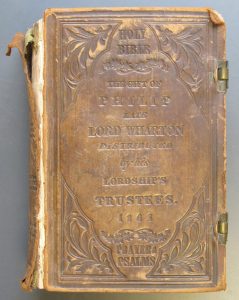

The second item is a nineteenth-century volume containing the English Bible, the Book of Common Prayer and the metrical psalms in the version of Tate and Brady all bound together. Such an arrangement was commonplace from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries. Before the advent of the Victorian hymn book, translations of the psalms into English verse were the main outlet for congregational singing in the Church of England, and a Bible, Prayer Book and psalm book bound in one would form a complete manual of Anglican worship. The interest of this particular copy lies in the binding, now very worn, which is stamped with the legend “The gift of Philip late Lord Wharton, distributed by his Lordship’s Trustees. 1863”.

Lord Wharton’s Charity, which is still in existence, was founded by the will of Philip, 4th Baron Wharton (d. 1696). Initially confined to Wharton’s home county of Yorkshire, it provided for the yearly distribution of Bibles to poor children able to recite certain Psalms from memory. Wharton was a lifelong Nonconformist, and his charity also provided copies of the Shorter Catechism drawn up by the Puritan Westminster Assembly in 1646-7. By the nineteenth century the charity appears to have moved to a more mainstream religious position, and the Book of Common Prayer was substituted for the Catechism. A Wharton Bible bound in the same fashion as ours survives at Haworth parsonage, with notes by Patrick Brontë suggesting it was presented to one of his children (see Craig, Lydia “The Devastating Impact of Lord Wharton’s Bible Charity in Wuthering Heights” Victorians no. 134, (Winter 2018), pp. 234-249).

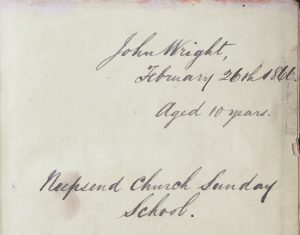

Our copy appears to have been presented to a John Wright, then aged 10, of Neepsend, near Sheffield, in February 1866. In addition to the clasped calf binding, specified in Wharton’s will, the volume has a specially printed title page listing the contents and again giving the name of the charity. There are no marks in the text to tell us how assiduously Master Wright read his new Bible, but the dilapidated state of the binding suggests that it was much used over the next century or so.