Giovanni Belzoni and his ‘Book of breathings’

In Ancient Egyptian culture, matters relating to death and the afterlife were of great significance, as both the body and the soul were believed to survive after death. The body was embalmed to ensure its survival by chemical means. The soul was helped on its way through the underworld by specially written funerary texts called Books of the Dead, generally written on papyrus and illustrated with figures of gods, humans and animals taking part in funerary ceremonies. These date from around 1550 BCE until about 50 CE and contain prayers and magic spells intended to assist a dead person’s underworld journey. They were to be found in the coffin or tomb of the deceased.

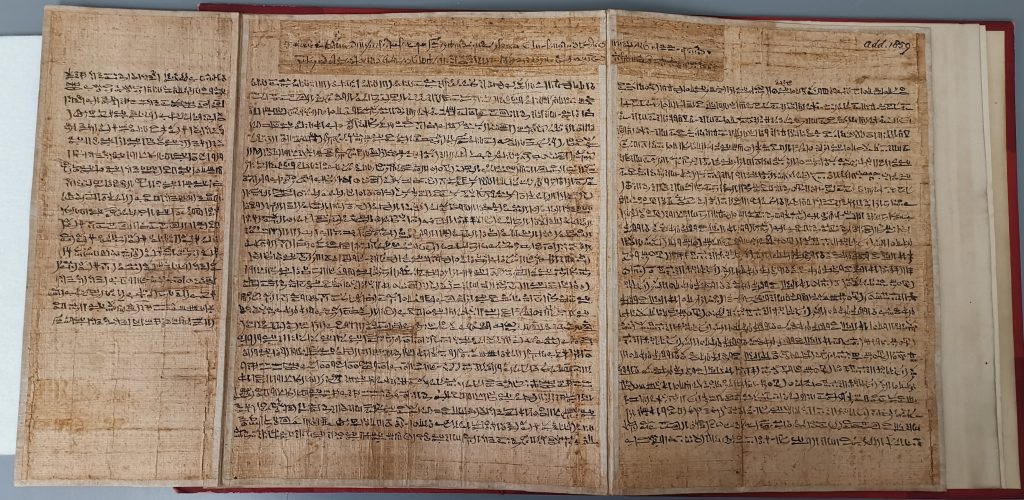

There was no single text of the Book of the Dead and surviving copies contain a variety of religious and magical texts. They were usually written in Hieroglyphic script which subsequently developed into the cursive form of writing, called Hieratic, around 3200–3000 BCE. Hieratic, which is read from right to left, continued its use as a writing system into the into the Hellenistic Period but around 660 BCE, a more cursive script called Demotic arose in northern Egypt and usually replaced Hieratic for everyday texts. Texts entitled Books of Breathings are also examples of a briefer form of funerary text. The earliest known copy dates to about 350 BCE but later copies date from the Ptolemaic Kingdom (323 BCE – 30 BC) and the period of Roman rule as late as the 2nd century CE. The word “breathings” is used as a metaphor for all the aspects of life that the deceased hoped to experience once again in the afterlife.

The Library possesses a copy of The Book of Breathings written on a single large sheet of papyrus folded into three sections and mounted on a canvas backing. It is folded neatly into a rigid binding with a red leather spine which must have been added to protect the papyrus at the time it entered the Library. The main text is written in Hieratic with two lines of Demotic across the top containing the title, but probably written around the same date. It most likely dates from the Ptolemaic period but sitting among other volumes of manuscripts on the Library shelves, this slim item gives little away as to its origins many centuries earlier than neighboring volumes.

MS Add.1859

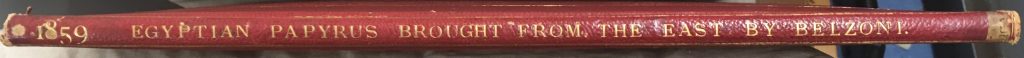

How did this volume come to be in the Library’s collections? The lettering on the spine is the only clue we have about how it arrived here. In gold lettering it states clearly ‘EGYPTIAN PAPYRUS BROUGHT FROM THE EAST BY BELZONI’. How Belzoni acquired the papyrus is uncertain; perhaps it was taken from a tomb or perhaps purchased on the antiquities market. Piecing together the background to this puzzle brings to light a fascinating story.

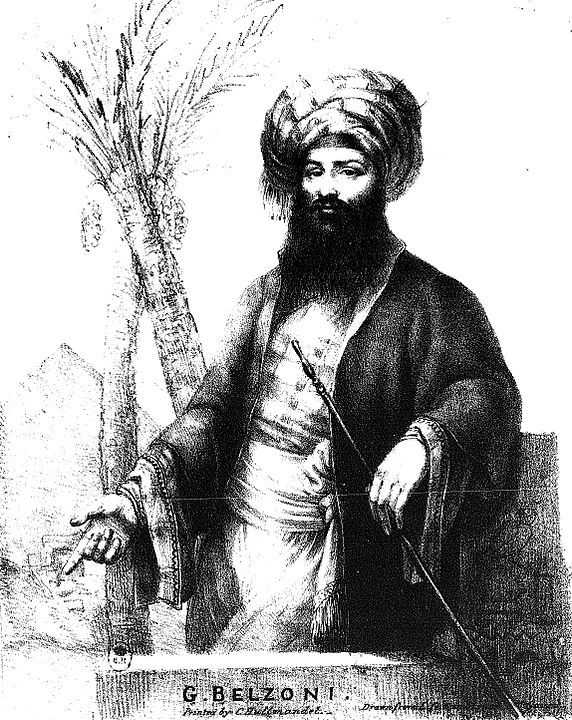

Giovanni Battista Belzoni (1778-1823) was an explorer and archaeologist of Egyptian antiquities. He was born in Padua, though later he went to work in Rome, to study hydraulics. He was a tall man, at 6 feet 7 inches tall, and with a muscular frame. In 1803 he fled to England and there he married an Englishwoman named Sarah Bane. Both he and his wife were able to subsist for a while as performing artists demonstrating feats of strength and agility.

In 1812 Belzoni left England and in Malta he met an emissary of the Egyptian Pasha, Muhammad Ali, who was carrying out a program of irrigation works in Egypt. Belzoni wanted to show the Pasha his own hydraulic machine designed to raise the waters of the Nile, and though the experiment with this engine was successful, the project did not meet with the Pasha’s approval.

But Belzoni resolved to continue his travels in Egypt where he met the traveler John Lewis Burckhardt and the British Consul in Egypt, Henry Salt. The three of them became friends and collaborators. They successfully planned and carried out the removal from Thebes of the bust of Ramesses II, shipping it to England, where it is still displayed in the British Museum. Weighing over 7 tons, it took Belzoni and his team 17 days and 130 men to tow it to the Nile to begin its journey to England.

In 1817, Belzoni discovered the tomb of Seti 1 and successfully cleared the sand from the entrance to the tombs at Abu Simbel, discovered by Burckhardt. In 1818, he found the entrance to the Pyramid of Khafre at Giza. In 1819, Belzoni returned to England and published an account of his travels and discoveries and during 1820-21 he exhibited facsimiles of the tomb of Seti I at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly in London. In 1823, Belzoni turned his attention to expeditions of discovery and setting out for West Africa, and intending to travel to Timbuktu via the Guinea Coast route, he caught dysentery at the village of Gwato in Benin and died there.

Belzoni was always saddened by the lack of recognition he received in Europe, especially in comparison to other contemporaries, for his contribution to the rediscovery of ancient Egyptian culture.

There is no evidence that Belzoni ever visited Cambridge, though he may have known of his friend Burckhardt’s fondness for the University where he had studied Arabic in 1808. But Belzoni had a friend in George Adam Browne (1774-1843), the Bursar and later Vice-Master of Trinity College to whom he trusted his financial affairs. So it was perhaps to Browne that Belzoni gave his copy of The Book of Breathings and Browne passed it on to the Library.

Belzoni is to be celebrated in his native city of Padua in its forthcoming exhibition Belzoni’s Egypt. A giant in the Land of the Pyramids; Padua, Cultural Center Altinate – San Gaetano; 25 October 2019 – 28 June 2020. The Library is to loan the papyrus and several of Burckhardt’s notebooks to the exhibition celebrating the achievements of the city’s famous son.

The Fitzwilliam Museum is also celebrating Belzoni’s life in its current exhibition The celebrated Mr Belzoni: a cultural gift to the Fitzwilliam which is centred on the Museum’s recent acquisition of Jan Adam Kruseman’s posthumous portrait of the explorer, painted in 1824. The exhibition also focuses on Belzoni’s remarkable life and his gift to the Fitzwilliam in 1823 of the lid of the sarcophagus of Ramesses III.

So perhaps at long last, Belzoni’s contributions to the rediscovery of Ancient Egypt are being realised, and he would surely have been very proud that his achievements are being recognised in this way at last.

References

Belzoni, G.B. Narrative of the operations and recent discoveries …in Egypt and Nubia. John Murray, London, 1821

Smith, M. Traversing eternity: texts for the afterlife from Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt. OUP, Oxford, 2009

Hayes, S. The great Belzoni. Putnam, London, 1970