A surprising find among a librarian’s letters

Post by Emily Perdue.

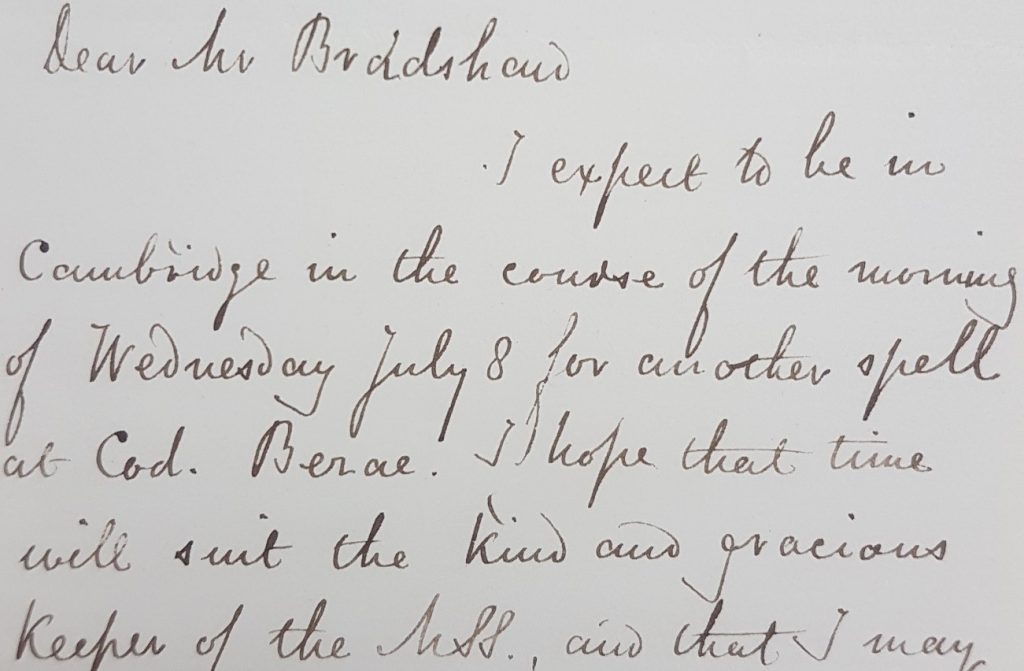

While working in the Manuscripts department, I have had the opportunity to document a significant portion of Henry Bradshaw’s letters. Henry Bradshaw (b. 1831) was University Librarian from 1867 until his death in 1886 and a well-regarded expert in manuscript studies. He was known by many to have an encyclopedic knowledge of medieval manuscripts, and he inherited a large collection of Irish books from his father, Joseph Hoare Bradshaw. He collected many manuscripts himself, purchasing volumes with his own money which he would go on to donate to the Library. After his death, his letters were also left to the library.

As a former Keeper of Manuscripts A.E.B. Owen notes, the immediate treatment of Bradshaw’s papers was “surprisingly casual” due to a lack of interest in personal papers. Batches of the papers were catalogued under different class marks throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries with the remainder of Bradshaw’s correspondence, MS Add.8916, being finally sorted and numbered by A.E.B. Owen himself in the 1990s. I set about the task of transcribing this information into a plain text form better suited for future publication and use. (https://specialcollections-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/?p=18329)

Much of Bradshaw’s correspondence in the collection deals with the daily management of the reading room, readers requesting certain items, book buying for the library, and the politics of King’s College and the University at large. There are also letters of a more personal nature, such as Bradshaw’s correspondence with his lifelong friend F.J. Furnivall, with whom he discusses the activities of the Chaucer Society. A common theme among correspondents is their chiding of Bradshaw for not writing to them more often or more swiftly. Henry was notorious for not responding to many of his letters and leaving disorganized stacks of letters around his office, occasionally burning up piles that he could no longer deal with!

While working with the collection, I came across an extra folder of letters that did not fit inside the rest of the boxes of Bradshaw’s notes and ephemera and had not been sorted or labelled. Perhaps the letters had been selected for cataloguing by a library employee in the 19th century? Maybe Owen found them after he had sorted through the rest of the letters? Whatever the case, I started to catalogue and identify this remaining group of letters. Much of it was easily identifiable and lined up with the same sort of correspondence catalogued by Owen. However, a smaller group of letters began to emerge that did not fit in with the rest. These letters stuck out visually at first, the paper being generally darker, thicker, and brittle. The other obvious difference was that a few of these letters were dated from before Henry’s birth. This batch of letters was isolated and given the separate class mark of Add.8916/1/K to represent a distinct grouping of correspondence. Two of the eight letters were addressed quite clearly to Joseph Hoare Bradshaw (1784-1845), Henry’s father. One of the letters is from William Boone, who, together with his brother Thomas, was a bookseller. Both of whom were also later correspondents of Henry. Most of the letters however were related to Joseph Lancaster (1778-1838), the educational reformer, or William Allen (1770-1843), a well-known Quaker philanthropist and abolitionist, who married into the Bradshaw family later in his life.

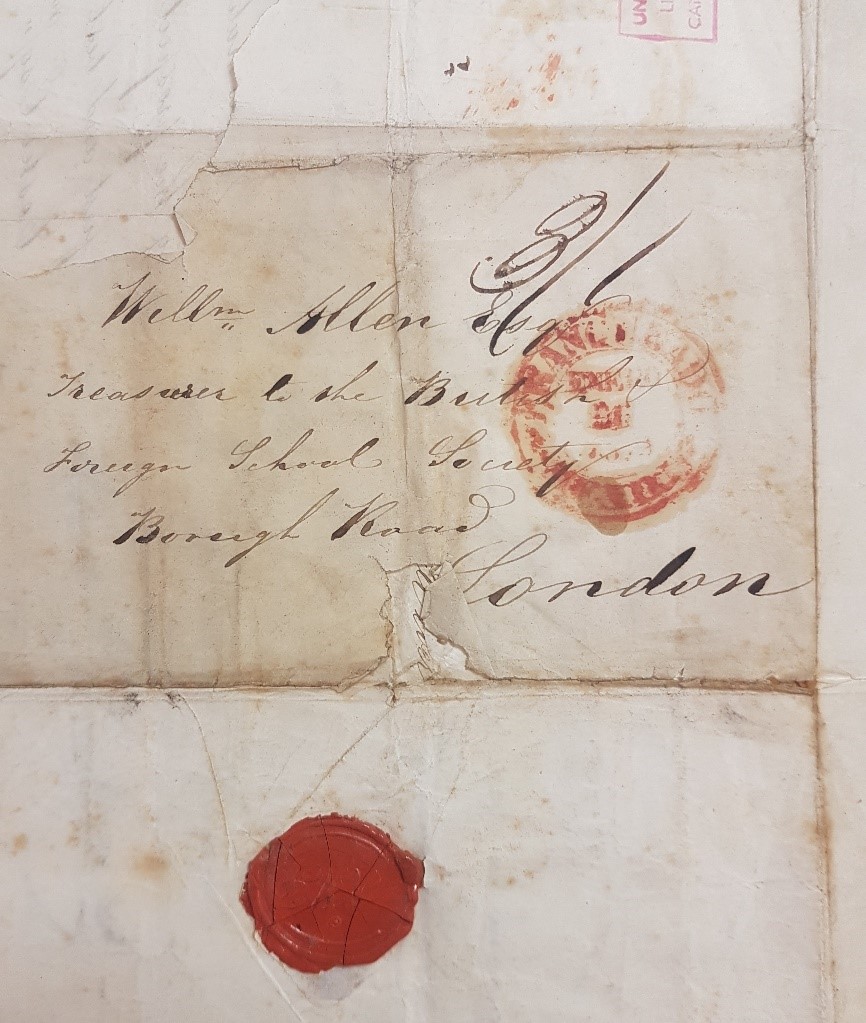

Letter addressed to William Allen, treasure of the British and Foreign Bible Society. MS Add.8916/1/K/

Joseph Lancaster was very good at starting schools but absolutely terrible at keeping accounts and planning expenditures, so much so that he was put in jail for debt in 1807. William Allen was critical in forming the British and Foreign School Society, the organization that took over management of much of Lancaster’s activities. The two had a close relationship though tension often arose between them over money and the fact that Allen and others were constantly monitoring Lancaster’s habits. Two of the letters, from an unidentified sender written in 1807, discuss Joseph Lancaster’s approach to education and religious training, which went hand in hand at the time. A much later letter, MS Add.8916/1/K/7, speaks to the close relationship between Allen and Lancaster. Richard M. Jones, Lancaster’s son-in-law, writes to William Allen in 1838 to find out where his father-in-law has gone, stating that when he last saw him, he was planning to go to England to see William Allen (possibly to discuss accounts). Unbeknownst to both men, Lancaster was actually in New York at the time where he subsequently died from injuries sustained from a runaway horse and carriage.

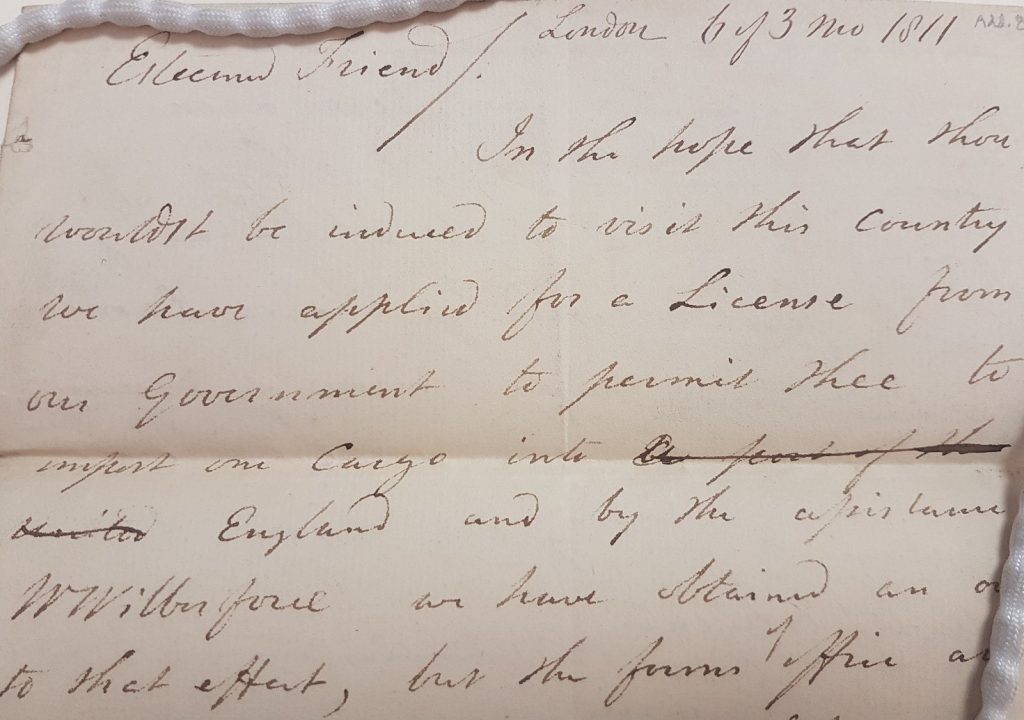

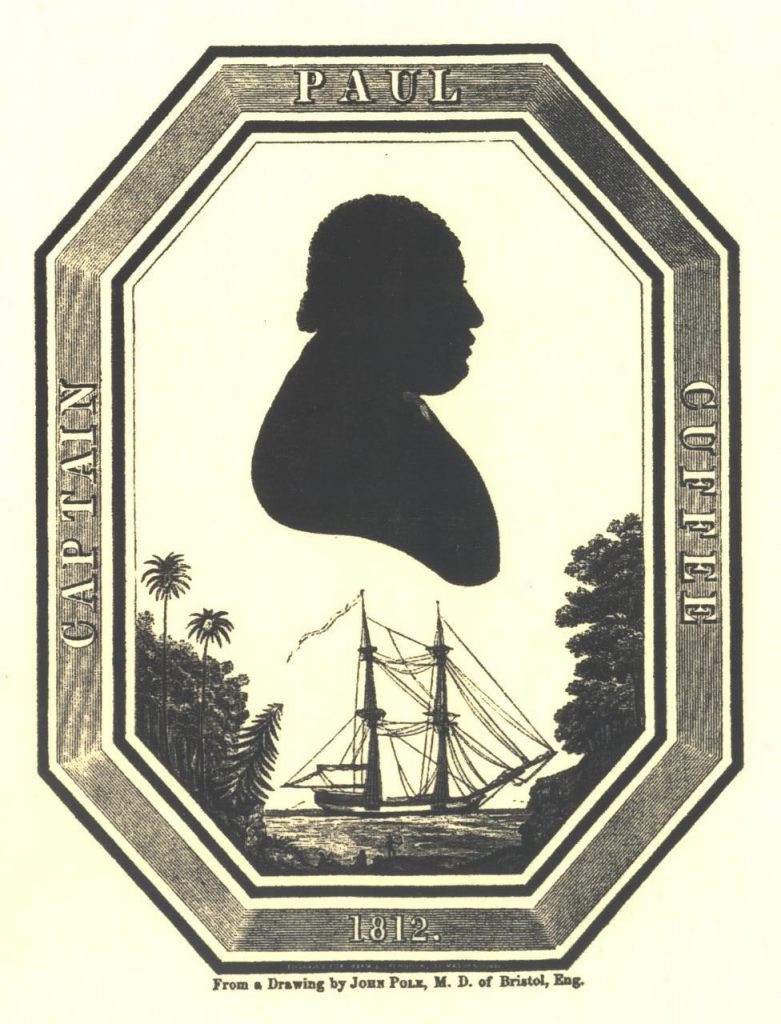

Another fascinating item in this collection is a letter from William Allen to Paul Cuffe, a free black American ship-owner and merchant, MS Add.8916/1/K/3. Cuffe travelled between Massachusetts, Sierra Leone, and Britain advocating for the settlement of free African Americans in Africa and was the first free black man to have a private meeting with a sitting US president. In the letter Allen lets Cuffe know that he has sought permission for him to trade freely, despite the tensions of the War of 1812. Allen was very interested in hearing what Cuffe had to say about the colonial project in Sierra Leone as he was a passionate abolitionist and also interested in the short-lived resettlement movement. Cuffe did eventually transport thirty-eight freed black Americans to Freetown, Sierra Leone, the first city in all of Africa founded by African Americans.

At the time, Paul Cuffe had only intended to sail to Sierra Leone. But a letter from William Allen, with an order in council, convinced him to visit England. Cuffe mentions in his journal that his visit was motivated in part to be able to see Joseph Lancaster’s school, which he wrote “was the greatest gratification that I met with.” Allen, for his part was able to learn more about the colonization project and left him, “in much nearness of spirit; he is certainly a very interesting man.”

How and why then did this important and remarkable letter end up in a collection of papers belonging to a medieval manuscript librarian? What interest did these letters hold for Henry Bradshaw? A future blog post will explore the connections between William Allen, a passionate and public political reformer, and Henry Bradshaw.

References

Doheny, John. “Bureaucracy and the Education of the Poor in Nineteenth Century Britain.” British Journal of Educational Studies, Vol. 39, No. 3

Owen, A.E.B. “Henry Bradshaw and his Correspondents.” Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society, Vol. 11, No. 4

Sherwood, Henry Noble. “In England.” The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 8, No. 2.

Fascinating blog post, and beautifully designed. I look forward to your next posting.