M. R. James and the ghosts of the old University Library

‘Wisdom will not expect the men of my generation or of several later ones to leave without a sore pang of regret the old home … ’ (M. R. James on the opening of the new University Library)

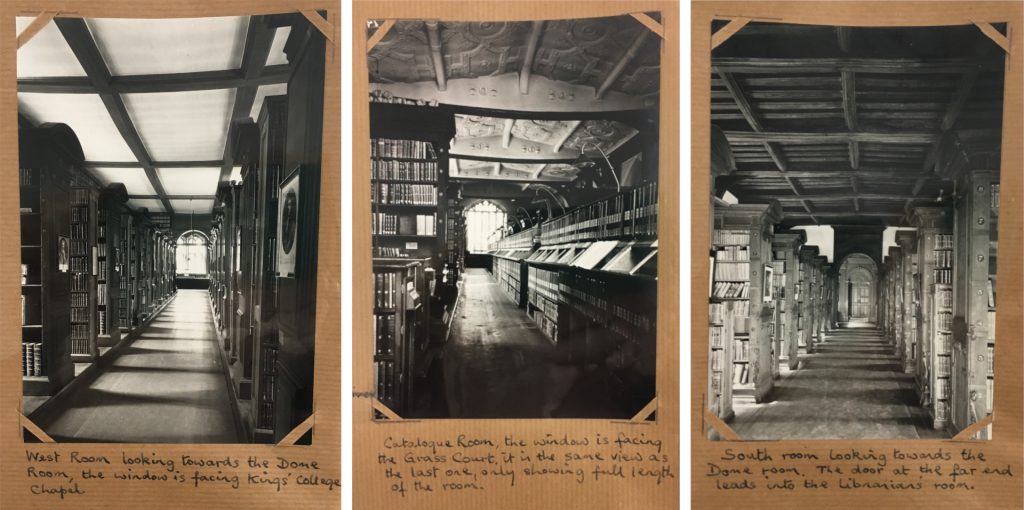

On 22 October 1934, eighty-five years ago today, the new University Library was officially opened by George V to rapturous celebrations and a day of flag-waving throughout the streets of Cambridge. The old library had closed to readers for the last time on 31 May that year, and over the next eight weeks some one-and-a-half million books moved to the new building west of the river. It had been a long goodbye. The old library in the ‘Schools’ buildings next to King’s College was a chaotic but atmospheric medley of disparate rooms, uneven floors and dark places for which readers could borrow lamps to light their way. It had overflowed with books for decades. The decision to abandon a site continuously occupied as the University’s library for over 500 years had finally been taken in 1921, but the foundations of the new library were not laid until 1931, following a decade of fundraising. It was business as usual at the old place, while a giant skeleton of steel and stone rose slowly from the ground less than half a mile away across the Backs. Contemporary accounts of the move pitch progress and modernity against medievalism, sentimentalism and nostalgia. Fondness for the old place is tempered by a commonsense acceptance of the necessity of the move. As the fundraising brochure of 1925 argued, ‘It is good to have a reverence for the past and to take a pride in historical continuity, but one can pay too high a price for clinging to mediaeval arrangements and to outworn traditions that hamper efforts and retard progress.’ [1]

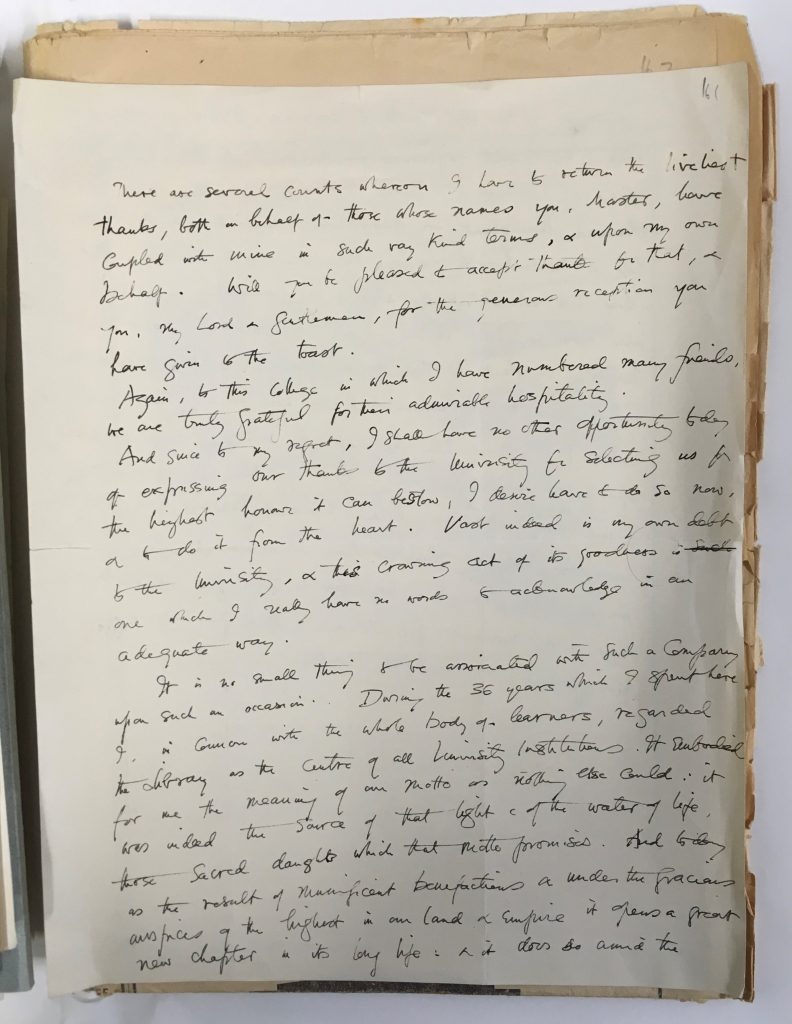

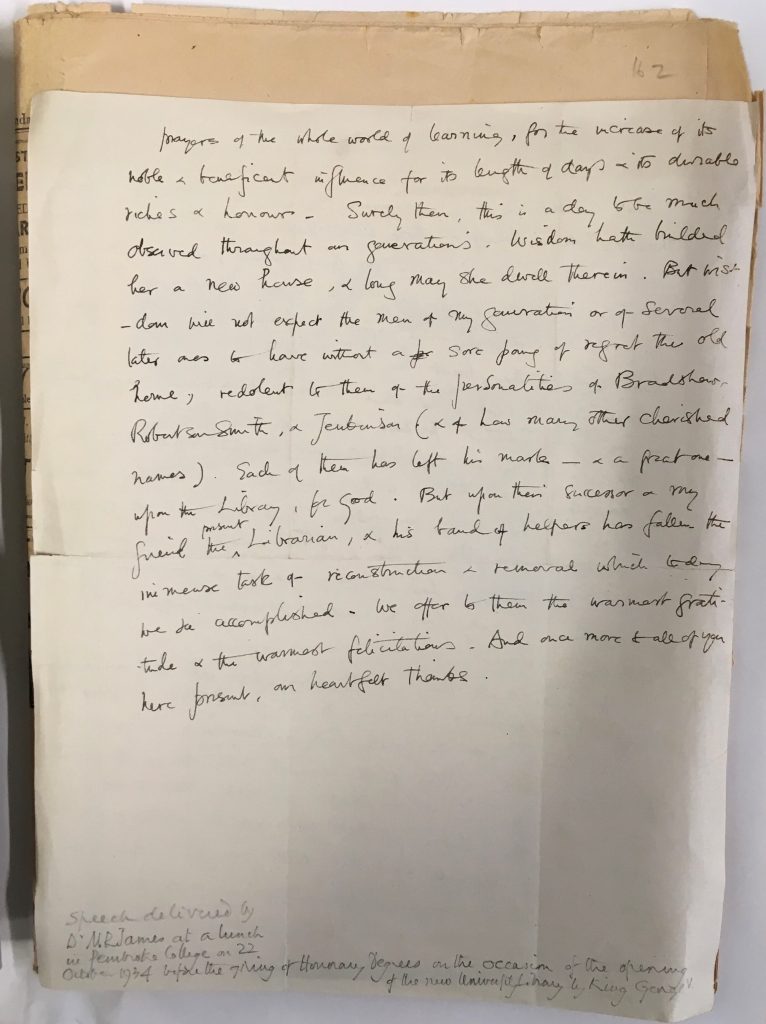

Amidst the noise and jubilation of 22 October, though, a different voice was heard. Tucked at the back of a folder of press clippings held in the University Archives, I recently came across a copy of the speech given by the scholar, Provost of Eton, and celebrated writer of ghost stories M. R. James on the day the new library opened.[2] James was one of several eminent figures to be awarded an honorary degree to mark the occasion (others included the American ambassador and the bibliographer A. W. Pollard), and on behalf of his fellow graduands he warmly thanks the University for ‘this crowning act of its goodness’, given on such a momentous day for the ‘whole world of learning’. Yet, in spite of his recognition of the significance of the occasion and the scale of achievement, his speech shifts and strikes a wistful note:

‘Surely then, this is a day to be much observed throughout our generations. Wisdom hath builded her a new house, & long may she dwell therein. But wisdom will not expect the men of my generation or of several later ones to leave without a sore pang of regret the old home, redolent to them of the personalities of Bradshaw, Robertson Smith, & Jenkinson (& of how many other cherished names). Each of them has left his mark – & a great one – upon the Library, for good.’

James had left Cambridge sixteen years previously to return to his old school Eton as Provost, having served as Provost at King’s for thirteen years (1905–1918), with two years as the University’s Vice Chancellor (1913–1915). His extraordinary Cambridge career also saw him serve on the Library Syndicate and produce catalogues of the colleges’ collections of medieval manuscripts, as well as those of the Fitzwilliam Museum, where he was Director from 1893 to 1908. After his return to Eton, his Cambridge connections endured. From 1926 to 1930, at the invitation of his friend the University Librarian A. F. Scholfield, James worked on a catalogue of the medieval manuscripts at the University Library, though this was never published.

James memorably brought the old library to life in ‘The Tractate Middoth’ (published in More ghost stories of an antiquary, 1911), evoking the strange atmosphere of a place that was hard to navigate, especially in the fading light, a place disturbingly and memorably haunted by a becloaked reader with cobweb covered eyes and ‘an unnaturally strong smell of dust’.[3] This long vanished world in which assistants could be summoned to fetch books from the gloomy depths reveals James’s intimate knowledge of a place he loved. In his stories James, perhaps more than any writer, conveys the strange potency of the material world, of how places and things are imbued with the latent power to channel the immaterial. James’s sense of regret stems not from a sentimental attachment to ‘spiral stairs and narrow galleries’.[4] For James, the old library was somewhere ‘redolent’ of his departed friends, where the past tipped into the present through the deep connection of people and place. By invoking the shades of Bradshaw, Robertson Smith and Jenkinson, James – by then seventy-two years old – speaks an elegy for long-missed companions.

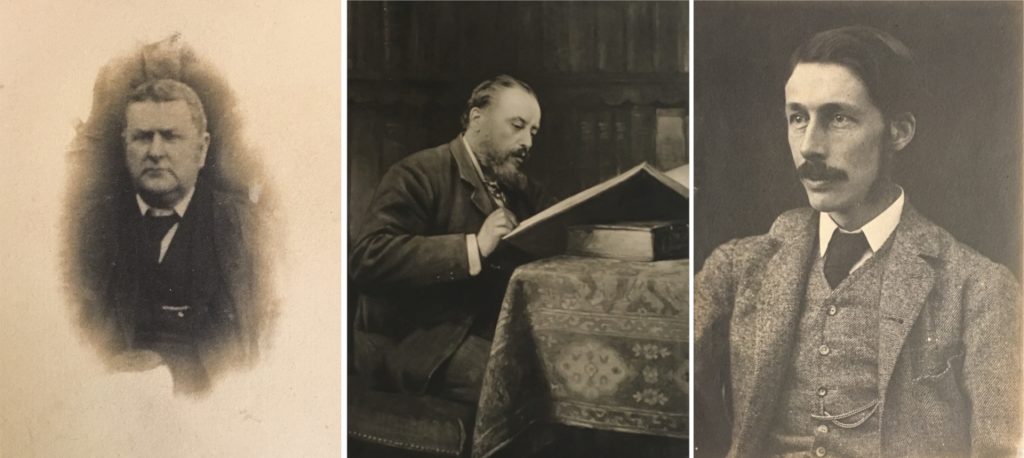

Bradshaw, Robertson Smith and Jenkinson – three successive University Librarians spanning over half a century, from Bradshaw’s appointment in 1867 to the death of Jenkinson in 1923. Henry Bradshaw (1831–1886), the master, who laid the foundations for modern bibliographical and codicological methods that James went on to make his own. James sought out his company at King’s as a student and recollects evenings spent in service, tickling the great man’s palms. Robertson Smith (1846–1894), theologian and Semitic scholar, and University Librarian from 1886 to 1889, when he gave up the post on his appointment as the Adams Professor of Arabic. For James, ‘Robertson Smith came much nearer to taking all knowledge for his province than anyone else I have met … Have I not heard him quoting Persian poetry (unless it was Arabic) by the yard, capping E. G. Browne?’ Francis Jenkinson (1853–1923), nine years James’s senior, appointed University Librarian in 1889, the same year in which James took up Directorship of the Fitzwilliam Museum, and whom James admiringly recollected ‘possessed in a marvellous degree’ ‘the sort of brain and eye … which carries in it the special form of the letter g (say) and can tell you with certainty that it does not occur after the year 850’.[5]

The loss of the old library was an irrevocable break with the past, marking out ‘men of [James’s] generation’ from those building the brave new Cambridge world. James, in his speech, seems deliberately to distance himself in this way – and while Wisdom has builded herself a new ‘house’, there is ‘a sore pang of regret’ for the old ‘home’. Staunchly conservative, ‘against modernity and progress’, we don’t know what James thought of the new place, but his sense of loss for the old one is keenly felt.[6]

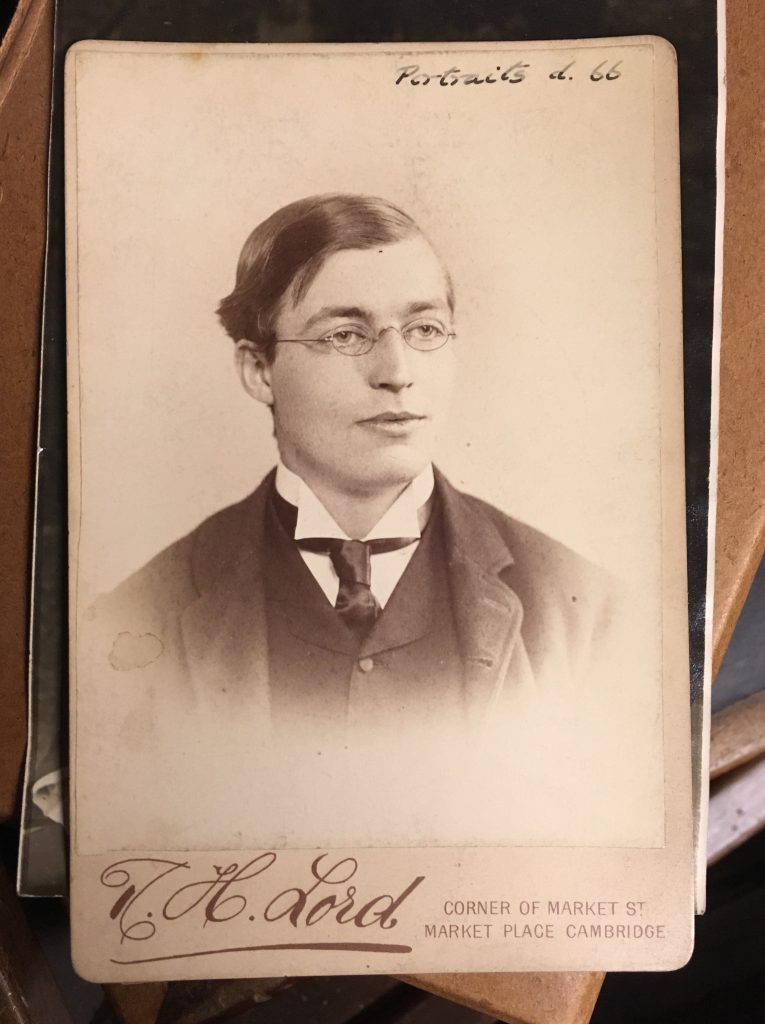

Less than two years later, James was dead, but his ghosts – Bradshaw, Robertson Smith, Jenkinson – and James himself are still with us. Those of us lucky enough to work today at the University Library still feel their presence, in their penciled notes on the old books and manuscripts, in the profound legacy of their collecting and scholarship. Not a haunting, though in quiet moments a visit to one of the darker corners of the Rare Books stacks to view their portraits can feel like such. Roberston Smith, Jenkinson in youth and age, the unsettling but beautiful photographs of the dead Henry Bradshaw. And M.R. James too, from young man half-smiling in his glasses, to the more somber portraits of his later years. Like the books they loved, somewhat displaced, but redolent still of the ‘old home’.

Notes

- Cambridge University Library: an appeal (Cambridge, 1925), p. 11.

- Cambridge, University Library, ULIB 9/4/18, Papers relating to the opening of the new Library by George V on 22 October 1934.

- M. R. James, More ghost stories of an antiquary (London, 1911).

- ‘Some criticisms are to be heard of [the new library], but they come generally from men who for sentimental reasons dislike leaving the spiral stairs and narrow galleries of the old library’, ‘King and Queen at Cambridge: new University Library opened’, Eastern Daily Press, 23 Oct 1934 (in Cambridge, University Library, Cam.bb.934.5, Cambridge University Library: 22 October 1934: press cuttings).

- M. R. James, Eton and King’s: recollections, mostly trivial, 1875–1925 (London, 1926), 111, 212, 199. Edward Granville Browne (1962–1926) was Professor of Arabic at Cambridge and Curator of Oriental Literature at the University Library in 1900, 1923 and 1924.

- A. C. Benson, quoted in Darryl Jones, ‘Introduction’, in M. R. James, Collected ghost stories (Oxford, 2001), xii.

Appendix

‘Speech delivered by Dr MR James at a lunch in Pembroke College on 22 October 1934 before the giving of Honorary Degrees on the occasion of the opening of the new University Library by King George V’ (transcribed from ULIB 9/4/18; reproduced with permission of Michelle Kass Associates)

There are several counts whereon I have to return the liveliest thanks, both on behalf of those whose names you, Master, have coupled with mine in such very kind terms, or upon my own behalf. Will you be pleased to accept thanks for that, & you, my Lord & gentlemen, for the generous reception you have given to the toast.

Again, to this College in which I have numbered many friends, we are truly grateful for their admirable hospitality.

And since to my regret, I shall have no other opportunity today of expressing our thanks to the University for selecting us for the highest honour it can bestow, I desire leave to do so now, and to do it from the heart. Vast indeed is my own debt to the University, & this crowning act of its goodness is such one which I really have no words to acknowledge in an adequate way.

It is no small thing to be associated with such a company upon such an occasion. During the 36 years which I spent here I, in common with the whole body of learners, regarded the Library as the centre of all University Institutions. It embodied for me the meaning of our motto as nothing else could: it was indeed the source of that light & of the water of life, those sacred delights which that motto promises. And today as the result of munificent benefactions & under the gracious auspices of the highest in our land & Empire it opens a great new chapter in its long life: & it does so amid the prayers of the whole world of learning, for the increase of its noble & beneficent influence for its length of days & its durable riches & honours. Surely then, this is a day to be much observed throughout our generations. Wisdom hath builded her a new house, & long may she dwell therein. But wisdom will not expect the men of my generation or of several later ones to leave without a sore pang of regret the old home, redolent to them of the personalities of Bradshaw, Robertson Smith, & Jenkinson (& of how many other cherished names). Each of them has left his mark – & a great one – upon the Library, for good. But upon their successor & my friend the present Librarian, & his band of helpers has fallen the immense task of reconstruction & removal which today we see accomplished & we offer to them the warmest gratitude & the warmest felicitations. And once more & all of you here present, our heartfelt thanks.