Henry Bradshaw – his quaker connection

Post by Emily Perdue

In my previous blog entry, I described a group of letters associated with William Allen, and other Quaker reformers, in the possession of Henry Bradshaw, University Librarian from 1867 to 1886. The two men were very different. Allen died when Bradshaw was only twelve years old, held different religious beliefs, practised different professions, and moved in very different social circles. Bradshaw never married, while Allen did, and Allen drew a lot of public attention while Bradshaw was known primarily within the university. However, it would appear that Henry was interested enough to hold on to some few records of William Allen’s life and motivations. How and why did they end up among Henry Bradshaw’s papers?

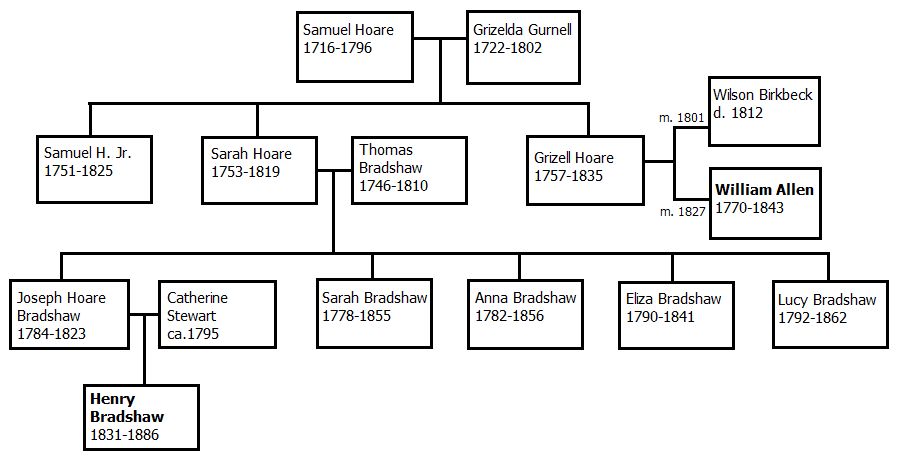

Given the inclusion of letters addressed to Joseph Hoare Bradshaw, Henry’s father, and letters to and from William Allen, I initially looked into possible connections between the two men. Both Joseph and William worked or resided on Lombard Street in London in the early 1800s and a “J. Bradshaw” appears on the subscription list for the British and Foreign School Society of which William Allen was treasurer. A less pleasant connection between the two men was a court case in 1835 to contest the validity of the will of Grizell Hoare (1757-1835), Joseph’s aunt and William’s wife. Grizell had written a new will in the presence of two witnesses, which would have left all of her money to her husband William. Joseph contested the will in court and eventually won the suit. Looking into the biographies of both Henry Bradshaw and William Allen however, a more subtle connection began to appear. Grizell Hoare’s nieces, were the relatives that maintained links with Henry Bradshaw and William Allen.

Henry Bradshaw’s grandfather Thomas was an Irish Quaker, and his grandmother, Sarah Hoare, was the daughter of a London merchant, Samuel Hoare. They had nine children, all raised in the Society of Friends. However Joseph later “conformed” to the Church of England after his marriage to Catherine Stewart. William Allen married another of Samuel Hoare’s daughters, Grizell, in 1827 becoming uncle to Joseph and the other Bradshaw children.

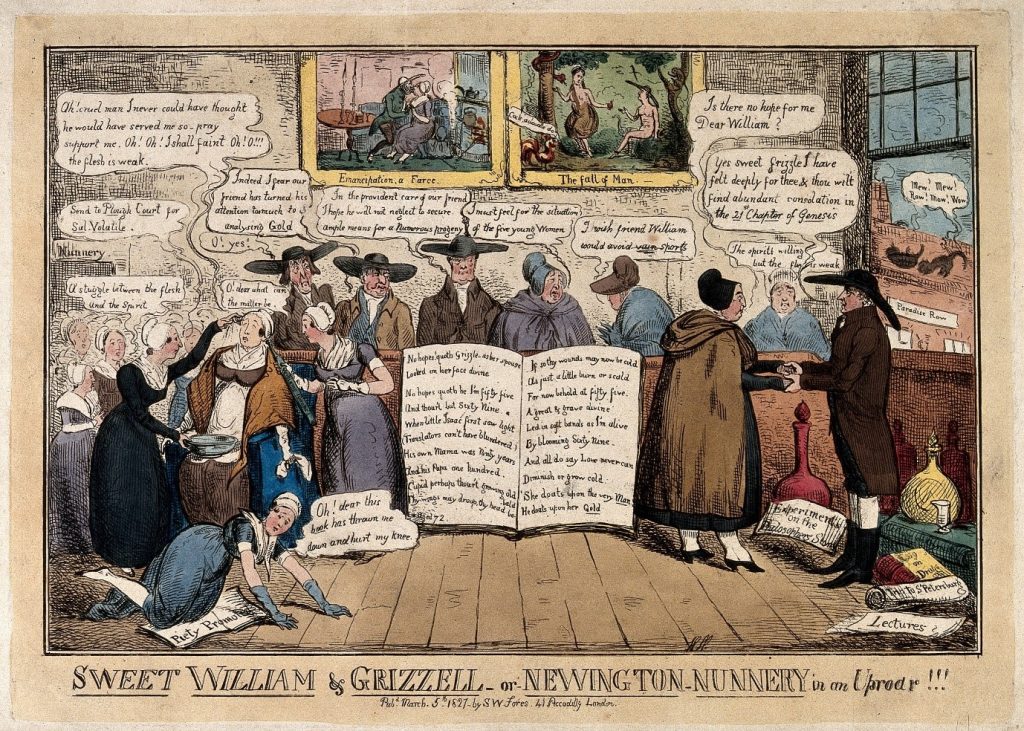

The marriage of Grizell Hoare and William Allen caused some controversy in the Friends community and drew the attention of the larger public. Grizell had been married previously to Wilson Birkbeck, another well to-do Quaker and had been widowed for fifteen years before remarrying at 69 years of age. The friendship between William and Grizell prior to their courtship was well known. It was however frowned upon for the two to marry for a third and second time respectively with little prospect of the union producing children. Friends of both wrote to the couple to discourage what they saw as a foolish late-in-life marriage. Contemporary caricaturists, such as Robert Cruikshank and Thomas Howell Jones produced mocking cartoons depicting Grizell as a wizened crone and Allen as a man in pursuit of funds to support his peculiar causes (such as abolition and education for the poor). In one of the cartoons, young Quaker women cry and grieve in the background, supposedly mourning the loss of a potential marital prospect in William Allen for themselves, or perhaps a possible dissolution of the Newington Academy for Girls, founded by Grizell in 1824 and run by Susanna Corder. Descriptions of these cartoons often specify that these young women are Grizell’s nieces, either Sarah, Anna, Eliza, or Lucy (Henry Bradshaw’s aunts) who were supposed to be jealous or upset.

Whatever hard feelings may have existed among these younger women, the written record after the marriage shows that the couple and their nieces were close. They all shared an interest in promoting educational reforms and charitable work. Grizell had no children of her own and was a doting aunt to her many nieces, possibly taking over the role of a maternal figure after the death of Sarah Hoare in 1819. During their marriage, Grizell and William were often accompanied by two of her nieces. Which two is not entirely clear and, indeed, the identity of Grizell’s unmarried nieces is often unstated. Eliza and Lucy Bradshaw both lived with Allen after the death of their aunt Grizell; Lucy, in particular, helping him manage charitable works and reading to him in his later years. In a memoir of William Allen by James Sherman, a short chapter near the end of Allen’s life is devoted to the sudden death in 1841 of his “precious E,” (Eliza Bradshaw) and records that she was buried besides his own mother’s grave in Stoke Newington.

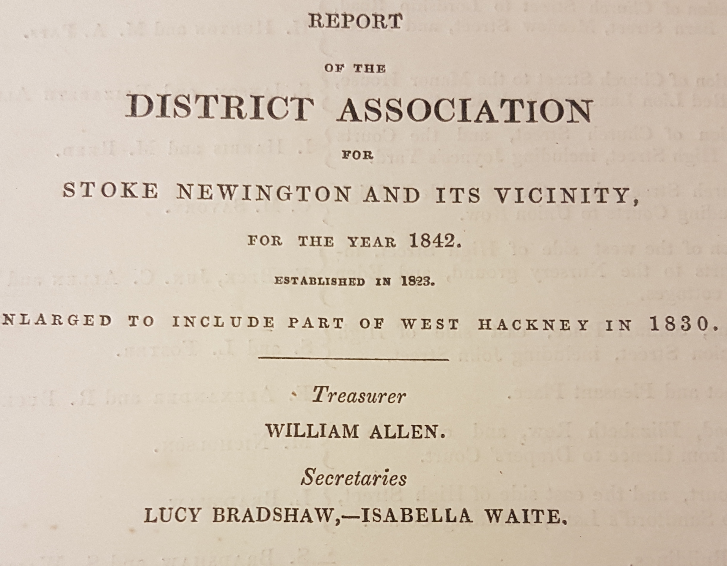

There are other records of a connection between several of Henry’s aunts and William Allen. Lucy Bradshaw and Allen were both officers of the Stoke Newington District Association in 1842, Lucy serving as secretary, and William as treasurer. Eliza, Sarah, Lucy are all listed as contributors or subscribers to the various charities that William Allen was heavily involved in, such as the Stoke Newington Soup Society and the Committee on African Instruction. In his will, William Allen left his manuscripts to Lucy Bradshaw and Susanna Corder, leaving instructions to destroy whatever was not “profitable to society.” How the two women decided which documents should survive on those merits is not recorded, but it seems that this was the most likely source of Henry Bradshaw’s small collection.

Henry Bradshaw’s relationship with his aunts developed between 1854 and 1856 when he was appointed Assistant Master at Saint Columba’s College in Dublin. He did not enjoy the administrative work of running the school, but while there, he was able to spend some time with his relatives and to study Irish manuscripts. Some of Bradshaw’s aunts had relocated to Dublin by this time. Bradshaw refers to his “perpetual aunts and cousins” in his letters. Bradshaw biographer John Crone attributes the aunts’ move back to Ireland to the death of their father, Thomas Bradshaw. However he died in 1810 and the two women remained in Stoke Newington long after. It seems more likely that the return to Ireland was spurred by the death of William Allen in 1843.

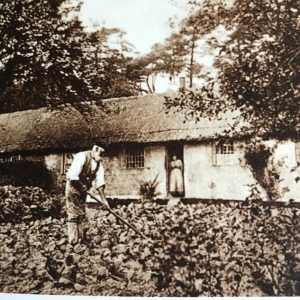

According to Henry’s biographers, he always held his Quaker relatives in high regard. Prothero quotes Bradshaw thus: “They live as simply as you could wish, and though I have no great fancy for Church principles carried to their full extent, yet there one lost sight of the forms in the solid reality of the undertaking. I never saw a place where they seemed used so purely as a means and not as the end of religion. When one knows the vast amount of good they did . . . it is a great comfort.” The author also describes a portrait of “the old Quaker William Allen,” hung in Bradshaw’s chambers and an edition of Horace’s Odes that came from the library of Allen to Bradshaw as a boy. Though Bradshaw did not hold on to all of his own letters, he did keep a few examples of the charitable, educational, and pharmaceutical newsletters bearing the signatures and inscriptions of his aunts and Allen himself. Aunt Lucy considered Henry her sole heir, and left her estate to him when she died. A significant part of that estate was a small property at William Allen’s planned agricultural community for the poor at Lindfield in Sussex. Biographers mention the colony as a note of interest, but do not state what Allen did with this property. The Lindfield cottages were eventually condemned and demolished in the 1930s and 40s after years of neglect. With more time and research, this family connection can be explored further, and we may learn what became of Henry’s own little Quaker cottage.

References

Nicolle, Margaret. William Allen: Quaker Friend of Lindfield 1770-1843. Lindfield: Margaret Nicolle, 2001.

Crone, John S., and Bibliographical Society of Ireland. Henry Bradshaw: His Life and Work. Dublin: Printed at the Sign of the Three Candles, 1931.

Prothero, G. W. A Memoir of Henry Bradshaw: Fellow of King’s College, Cambridge, and University Librarian. London: K. Paul, Trench, 1888.

Hello Emily, what interesting articles you’ve written – thank you.

I’m looking into the history of my great grandfather, Richard Bradshaw (1829-99), Henry’s older brother, who himself had a very varied and successful career in the navy ending up as a Vice Admiral, CB and receiving the thanks of Parliament for his part in the 1879 Zulu Wars.

My family also have a gloriously scrappy collection of Henry’s researches – lots of small, thin pieces of paper. I’d guess that it was these which were used to compile the 6′ x 4′ lacquered canvas family tree which is now in Australia – ” Genealogy – Bradshawes of Bradshaw, Haigh and Uplitherland – compiled from the original pedigree by Bells Lancaster Herald, from ancient records and other authentic evidences, and brought to the present date by J. Jules Petit, 1860″. It goes back to ‘Uchtred the Saxon Thane and includes William the Conqueror etc etc (about 250 names). The current owner is a direct descendant of Thomas 1824-84, Henry’s oldest brother but has given us permission to use a digital image which we’ve had printed out.

So much information, it’s hard for me to know what to do with it all….. Kind regards, Vivien

Hi there – this is fascinating. i have owned one of william allen’s cottages for 20 years – these were converted from the old workshops and dormitories of his school. I believe vice admiral richard bradshaw owned the cottages with hugh stewart (or stuart) bradshaw in or around 1850 – he may have bought them from william allen’s estate but having read your article and follow up comment, i am wondering if he was left them via Henry who in turn inherited them from lucy bradshaw? any light you can shed would be fabulous. Mary