Erotica comes to Cambridge

When one thinks of the great collections which Cambridge University Library has built up over its six centuries, erotic literature is probably not very near the top of the list. Illuminated manuscripts, Isaac Newton’s papers and the Cairo genizah: yes. Obscene illustrated smut: probably not. But the Library is full of surprises and our shelves contain all sorts of things you might not expect to find (by choice or by chance), just as our recent Tall Tales exhibition about the contents of the Tower showed. Since the late nineteenth century a special collection known as Arc (for arcana) has been maintained for books which have, by various generations of Library staff, been thought worthy of being kept separate from the rest of our stock. This collection (of which a browsable PDF is available online) has been enriched over the years not only by the copyright act, but also by private donations, notably from Stephen Gaselee (d. 1943), librarian successively of the Pepys Library and the Foreign Office, and the estate of the Cambridge classicist A. E. Housman.

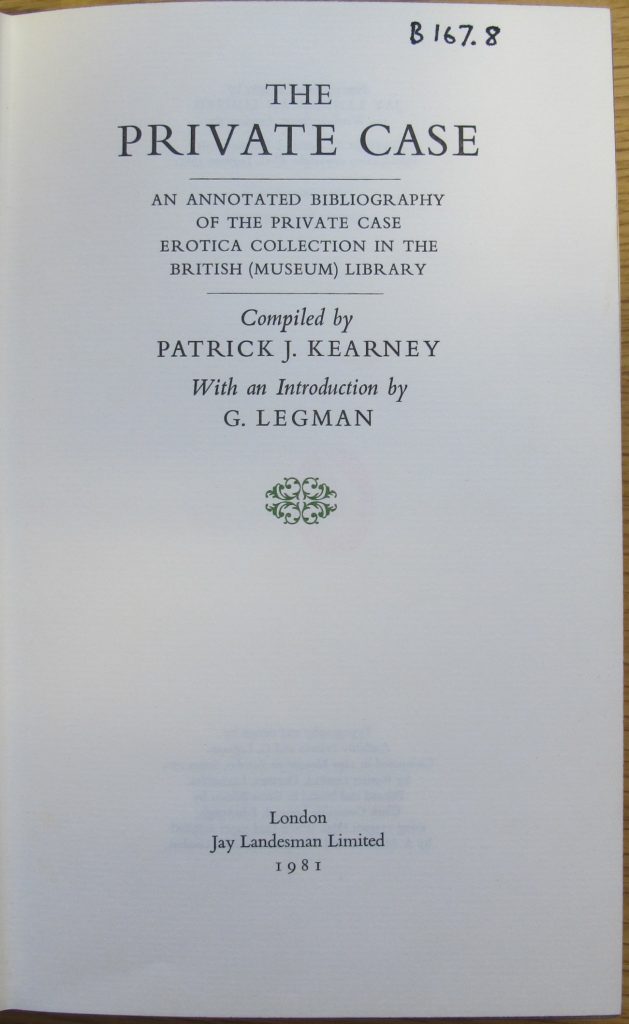

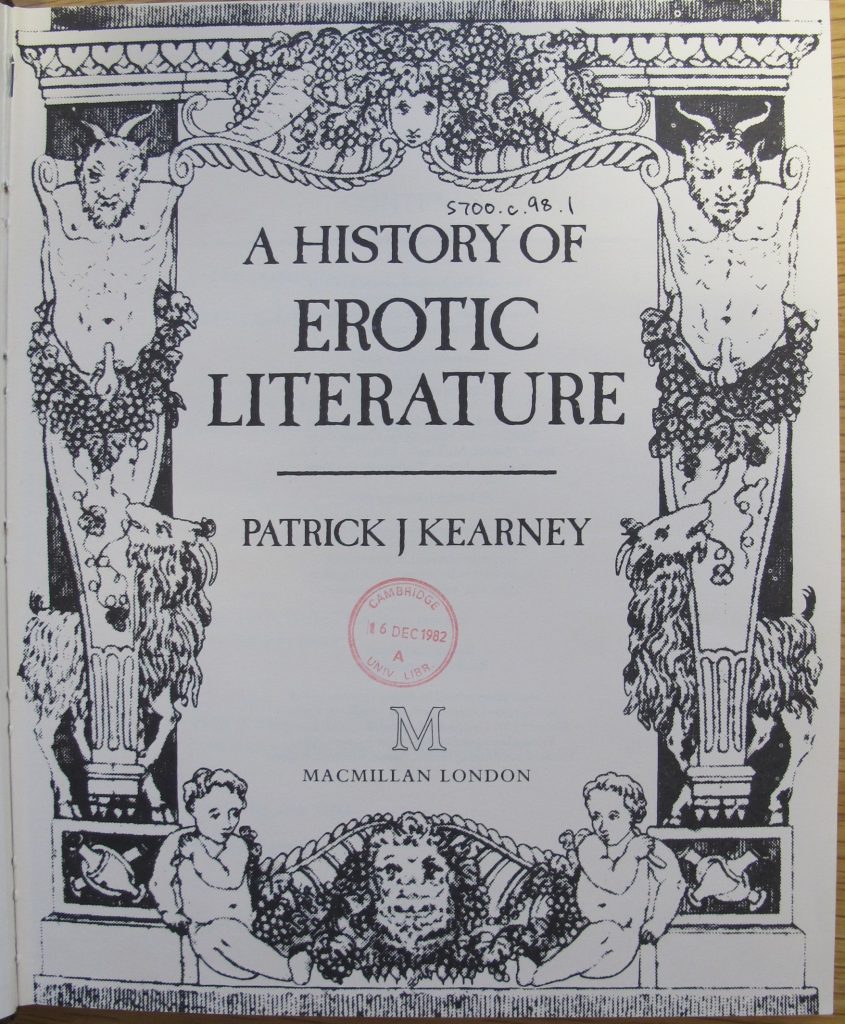

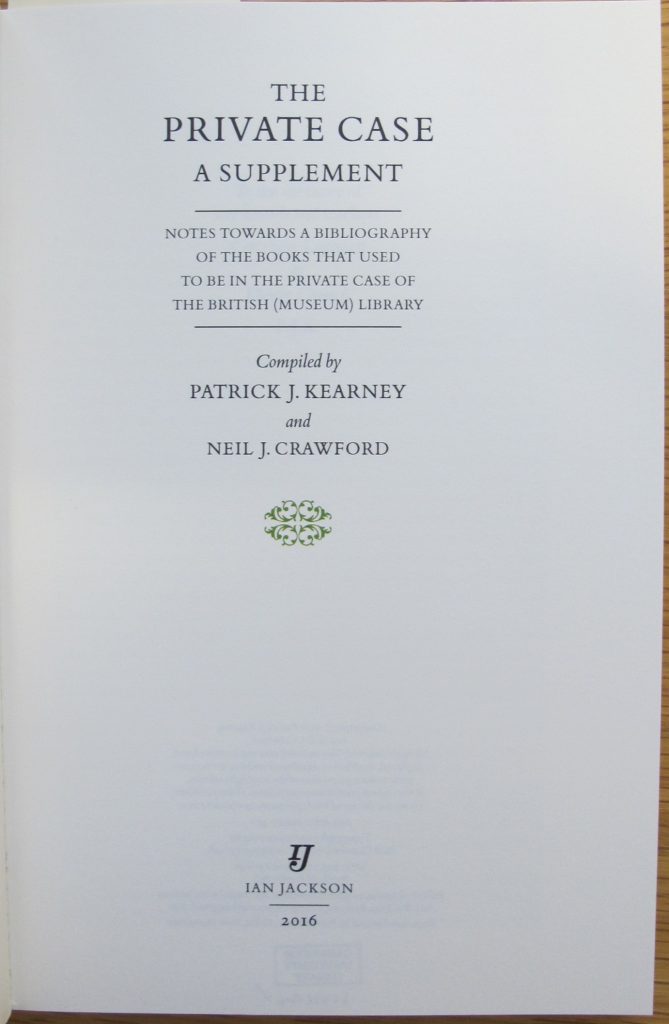

In 2017 the Library’s holdings of erotica were greatly enriched by a further generous donation, which this blog introduces, by the historian of erotic literature, Patrick J. Kearney. Born in London in 1943 Kearney now lives in California, and over the last forty years has written several major studies in his primary field of interest. Chief among these are his 1981 bibliography of the contents of the British Museum’s Private Case (its equivalent of Arc), a collection rich in private donations (notably the books of Henry Spencer Ashbee in 1900) whose contents were until relatively recently not very easy for readers to see. A general introduction to four centuries of erotic literature followed with Macmillan in 1982 (and involved a trip to the University Library, where a previously unknown copy of an exceedingly rare late eighteenth-century French work by Restif de la Bretonne was found), and in 1987 he published a study of the Olympia Press (founded in 1950s Paris by Maurice Girodias), which counted Nabokov’s Lolita (1955) among its more well-known titles, bound in distinctive green paper wrappers.

The collection (of which a PDF shelflist is available online) contains around 250 volumes, primarily from the first half of the twentieth century but with some items from the earlier or later periods, and is shelved with a number of other distinct author or subject collections at the class CCA-E.74. The clandestine nature of the publishing of erotic books over the years means that many editions in this donation will be rare in the UK; a quick calculation suggests over half were not hitherto represented in UK research libraries, with about a quarter being found in just one copy in this country (often the British Library). Since much literature of this nature was produced for discerning collectors, production values are often high, with fine papers used (often the same edition would have been available on a range of papers, as colophons often state), editions limited to small runs, and extra sets of illustrations sometimes slipped in.

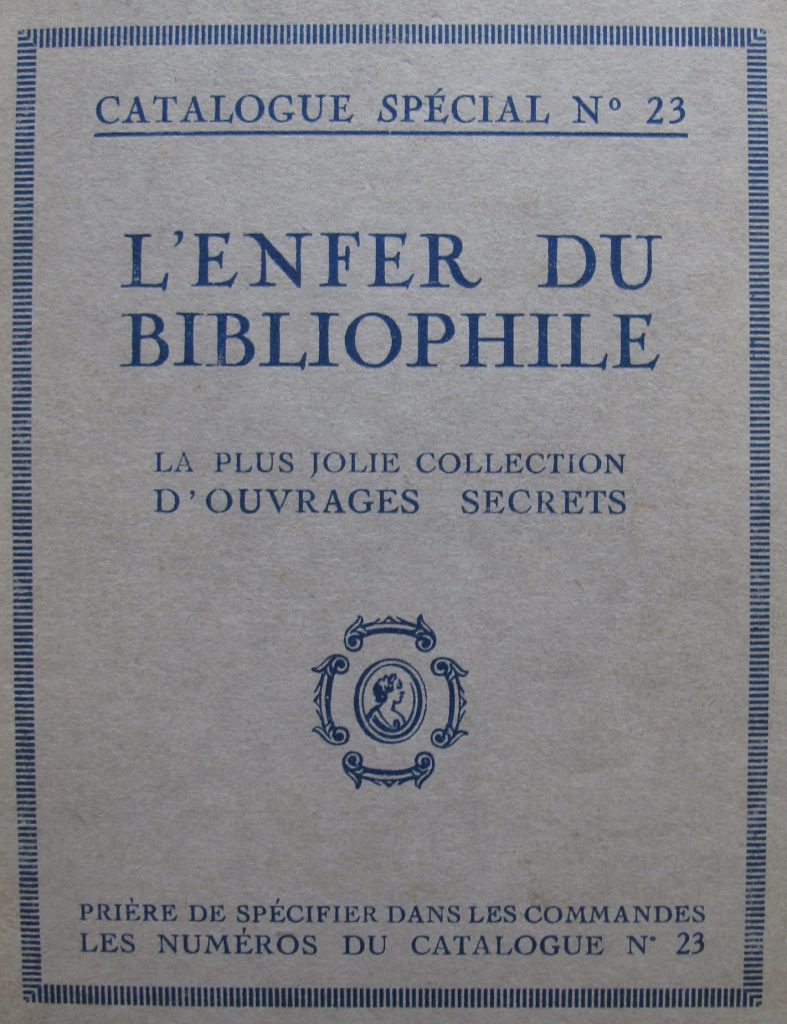

Other parts of the collection are more ephemeral, including (as above) booksellers’ catalogues from the early twentieth century, a 1973 guide to the International Museum of Erotic Art (unsurprisingly located in San Francisco), and the programme for a 1963 National Conference on Pornography, sponsored by the Public Morality Council of which the Archbishop of Canterbury was the Patron (then the Cambridge-educated Michael Ramsey). The books are primarily in French (a great centre of erotic book production) and many are illustrated. Some of the authors represented are well known, including the French poet Pierre Louÿs (1870-1925), friend of André Gide and the dedicatee in 1891 of the original French edition of Oscar Wilde‘s Salome. Some twenty-five editions of his work are to be found in the Kearney collection, complementing those to be found in the University Library’s Arc collection. Other authors are less well known, and others (like the places and dates of publication on the title pages) are entirely fictional, another feature of this clandestine world of underground publishing which provides headaches for the cataloguer.

One such example is the anonymously published Recueil de pièces choisies, rassemblées par les soins du cosmopolite, an 1860s reprint of a 1735 collection of erotic poetry. The original edition was printed on the private press of the French aristocrat the Duc d’Aguillon (possibly in as few as twelve copies), who had collected most of the contents from the manuscripts of the French lawyer and (oddly enough in this context) author of carols Bernard de la Monnoye. Many of the poems are thought to have been written for a group of noblemen and women who met on the Duc’s estate, under his protection, to engage in orgies, a tale which speaks of the aristocratic origins of much French erotica of the eighteenth century (for the full story see Legman’s Horn book, pp. 87-90). The Kearney copy of the 1860s reprint is one of only two copies in the UK, the other being at the British Library (presented by Eric Dingwall, former member of UL staff).

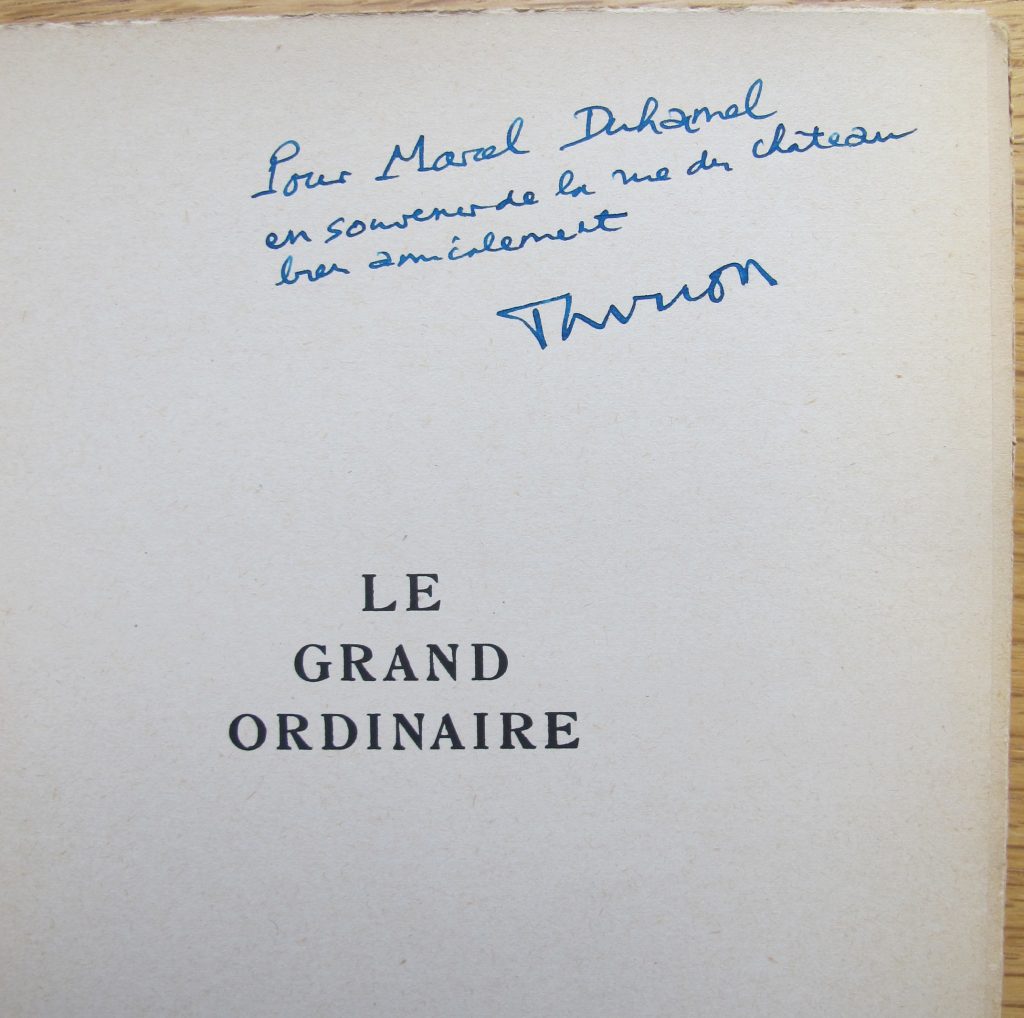

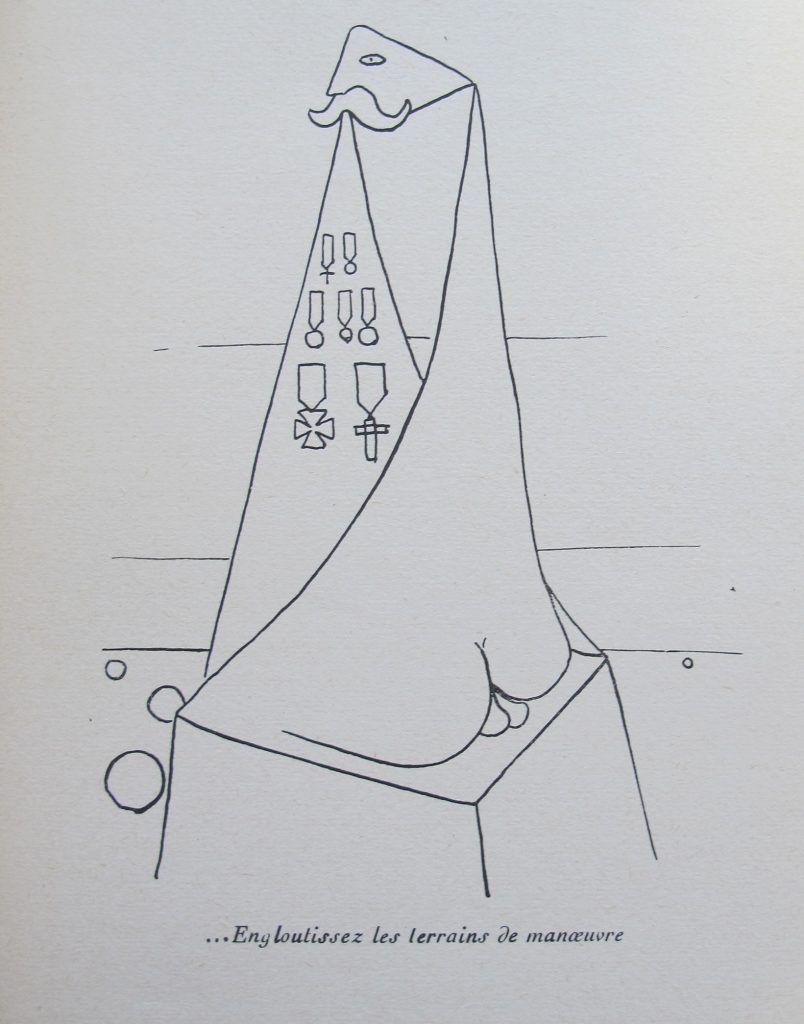

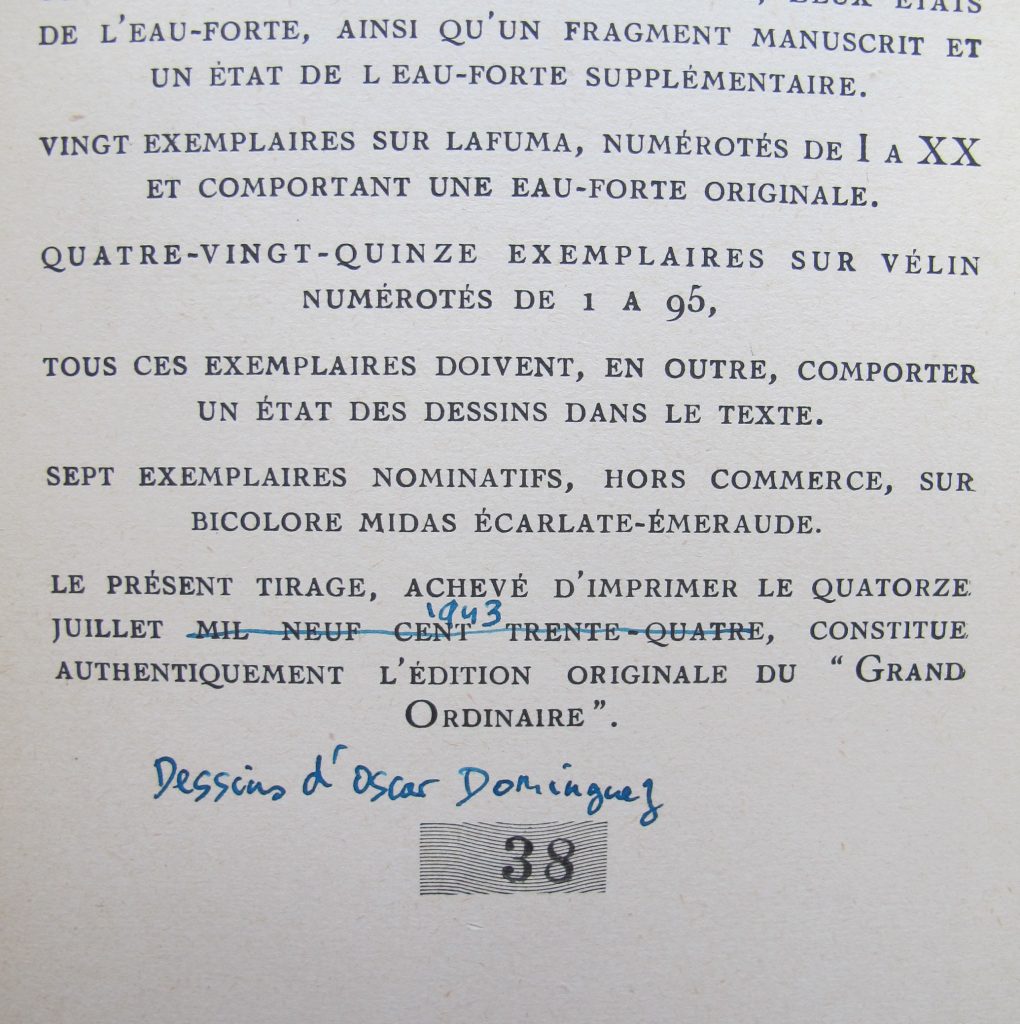

Of great interest within the collection are copy-specific features; annotations which speak of the networks of collectors through whose hands these books have passed, and which often reveal valuable information about the production of these books. The three images above come from one of the highlights: André Thirion‘s Le grand ordinaire (the only copy in the UK). A political activist and surrealist, Thirion wrote several erotic novels, alongside theatrical works and short stories, and contributed to the surrealist 1930s Parisian magazine Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution. The Kearney copy is interesting for a number of reasons. It is inscribed by Thirion on the half-title to the screenwriter and actor Marcel Duhamel, but most interestingly Thirion has annotated the colophon correcting the date of publication from 1934 to 1943, and giving the identity of the otherwise anonymous artist who provided its seven striking illustrations: Oscar Dominguez. A Spanish surrealist painter, Dominguez was – as the illustration above shows – heavily influenced by Picasso, and his pictures are now much valued by collectors.

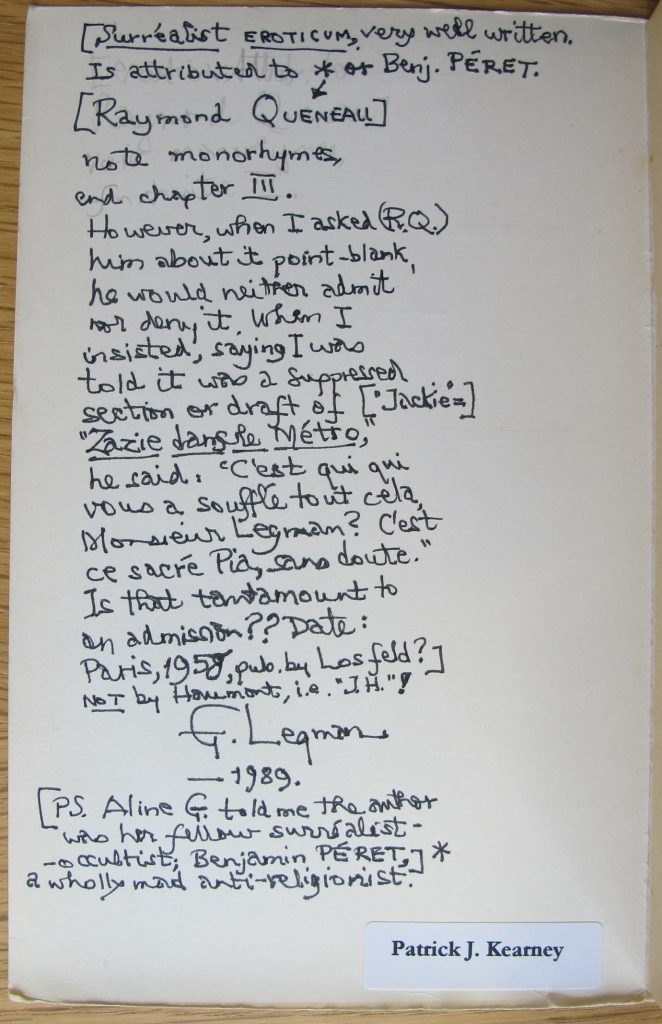

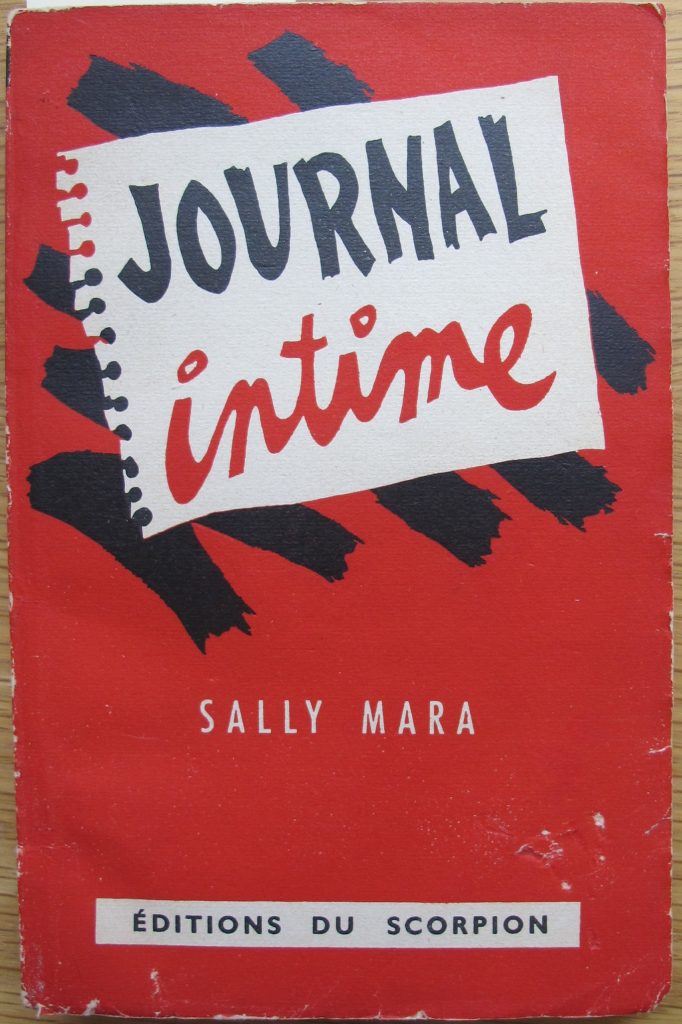

Another highlight is the anonymously authored La vie d’une sainte, again the only copy in the UK of this surrealist eroticum, and another book with rich copy-specific information which help us to understand its clandestine production. It came to Kearney from fellow erotica collector, Gershon Legman (who introduced his 1981 catalogue of the British Museum’s Private Case), who has helpfully recorded on the inside covers conversations with a number of individuals about its history. On the rear inside cover he notes that the ‘J.H.’ mentioned on the cover probably refers to Jacques Haumont (1899-1974), the French editor and printer, but that he ‘did not print or publish this’, adding that the publisher was likely Eric Losfeld in 1958 (the following year he published the novel Emmanuelle, later made into a film). Much more detail is found on the inside front cover, where his notes first suggest Raymond Queneau to have been the author, though Queneau himself when questioned would not deny or confirm his authorship. Finally Legman notes that the surrealist artist Aline Gagnaire confirmed Benjamin Péret to have been the author: a founder member and central figure of the surrealist movement, whose love of poetry had sprung from his discovery of Guillaume Apollinaire‘s work during World War One.

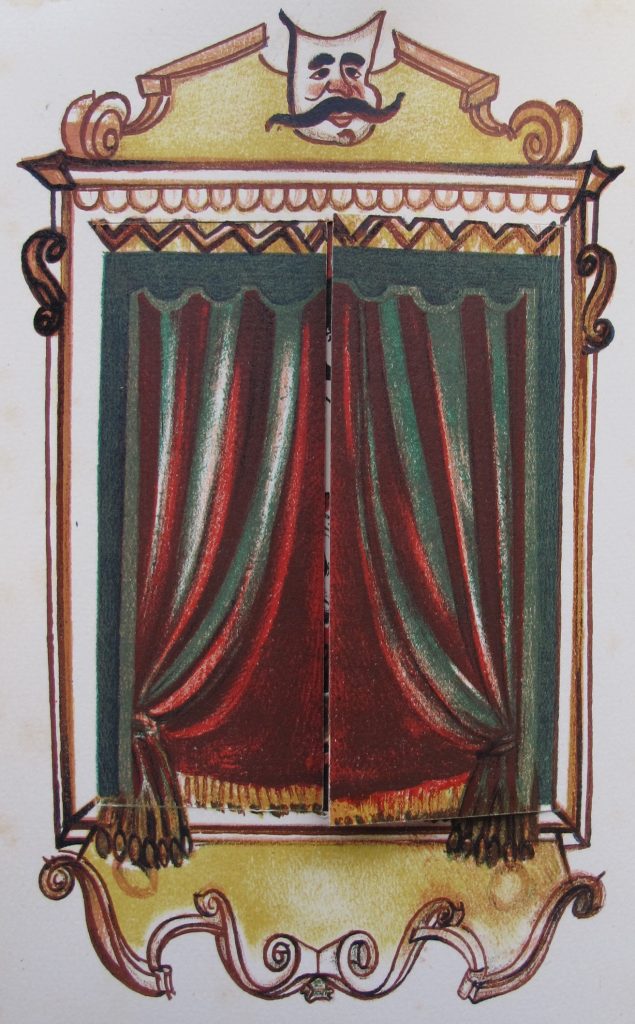

But whether valuable limited edition, or chance ephemeral survival, all parts of the collection come together to form a significant window onto literary and artistic erotica of the last century. The collection complements existing parts of the Library’s holdings, notably the Chadwyck-Healey collection on the liberation of Paris and the Martin Stone collection of French illustrated poetry, and its illustrated books are likely to be of interest to researchers in the field of twentieth-century (especially surrealist) art history (the folding window frontispiece to Guy de Maupassant’s A le feuille de rose above is certainly clever, hiding an interesting scene for the viewer to discover). The collection is now fully catalogued, with its contents findable in the Library’s iDiscover catalogue (and a list browsable here).