An earthen pot full of bones: true crime in Sutton

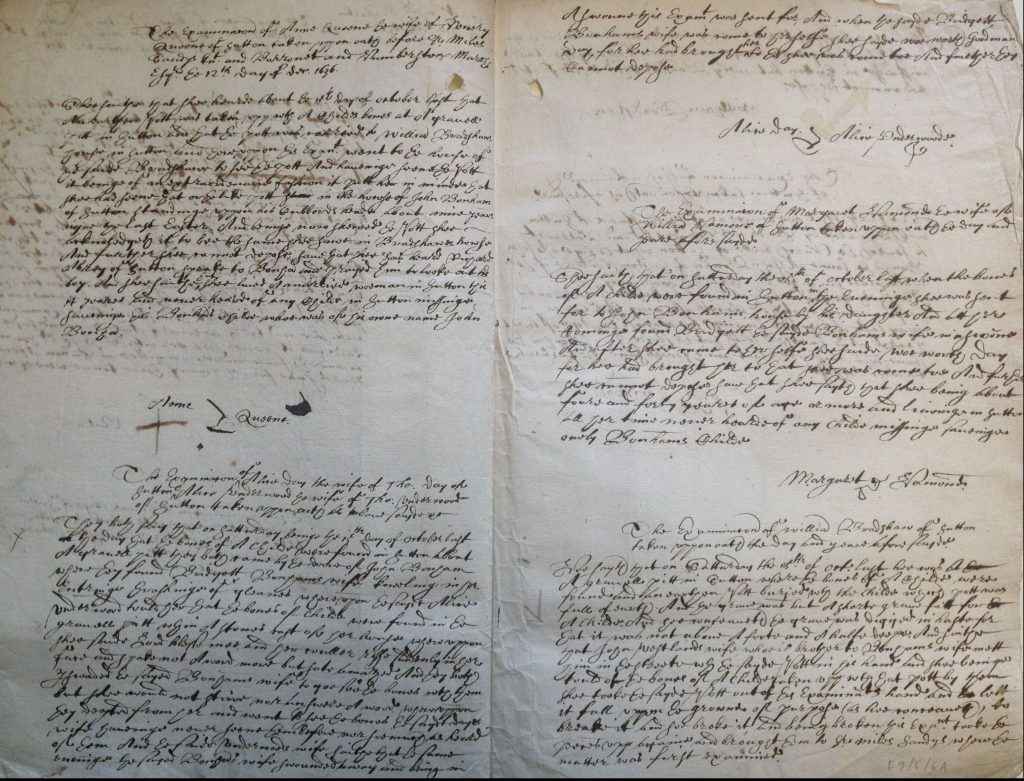

An extraordinary set of sworn testimonies in the assize files for the Isle of Ely shed light on the curious case of a missing child. Following the discovery of an earthen pot full of bones in a gravel pit in the village of Sutton in Cambridgeshire in 1636, suspicion of foul play soon fell on a local couple, John and Bridget Bonham, whose son was known to be missing. Sir Miles Sandys, Justice of the Peace, undertook a detailed investigation of the events, and heard 18 sworn testimonies or depositions.

‘ … never heard of any Childe in Sutton missinge saveinge this Bonhams Childe …’

On reading the depositions through, the evidence appears to mount up conclusively against the Bonhams. Multiple witnesses conclude their statements to Sandys by insisting that the only child they knew to be missing in Sutton was John Bonham junior. Added to this, several witnesses insinuate that John Bonham was cruel to his first wife, Grace, and that several of their children had run away. John married his second wife, Bridget, just seven weeks after the death of his first wife in 1620. Aside from testimony on the dynamics of the Bonham family, the deponents detail a litany of other suspicions from the immediate reaction of the Bonhams to the news of the discovery to speculation on the possible ownership of the pot, speculation on the size of the bones and on the state of the grave. The level of detail is extraordinary.

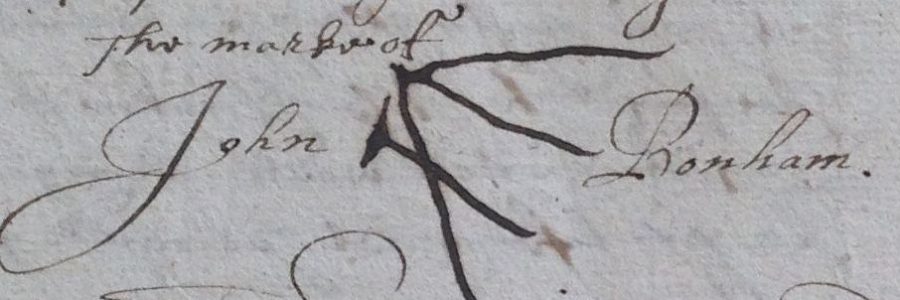

Sandys first concentrated on the behaviour of the Bonhams following the discovery of the earthen pot before widening his scope to consider the physical evidence. John and Bridget Bonham were examined by Sandys on 18 October 1636. Both denied any knowledge of the bones, with John stating he had last seen his son nine years ago but had been told of reported sightings of him at Cambridge and at nearby Longstanton. John Bonham was committed to gaol at Ely while Sandys investigated further.

The behaviour of Joan Westland, a sister of John Bonham, was soon deemed suspicious because she was reported to have broken the most damning piece of evidence, the earthen pot, when it was shown to her by a neighbour. In her deposition, Westland denied any malice by saying, ‘[the pot] slipped purposely out of her hand upon the ground to try what metal it was of and so broke the pot.’

Anne Queene testified that she recognised the earthen pot as the same one she had seen at John Bonham’s house about nine years earlier ‘standing upon his cupboard’s head’. The depositions also reveal that the pot in question was ‘duskish’ in colour with a seam about the middle and about the brim. Phebie Springe described it as a pot of ‘extraordinary fashion’ which she had not seen the like of anywhere else except in John Bonham’s house – ‘she said she dare not depose it to be the same pot for that one pot is like another though for her part she never see any other of that fashion’.

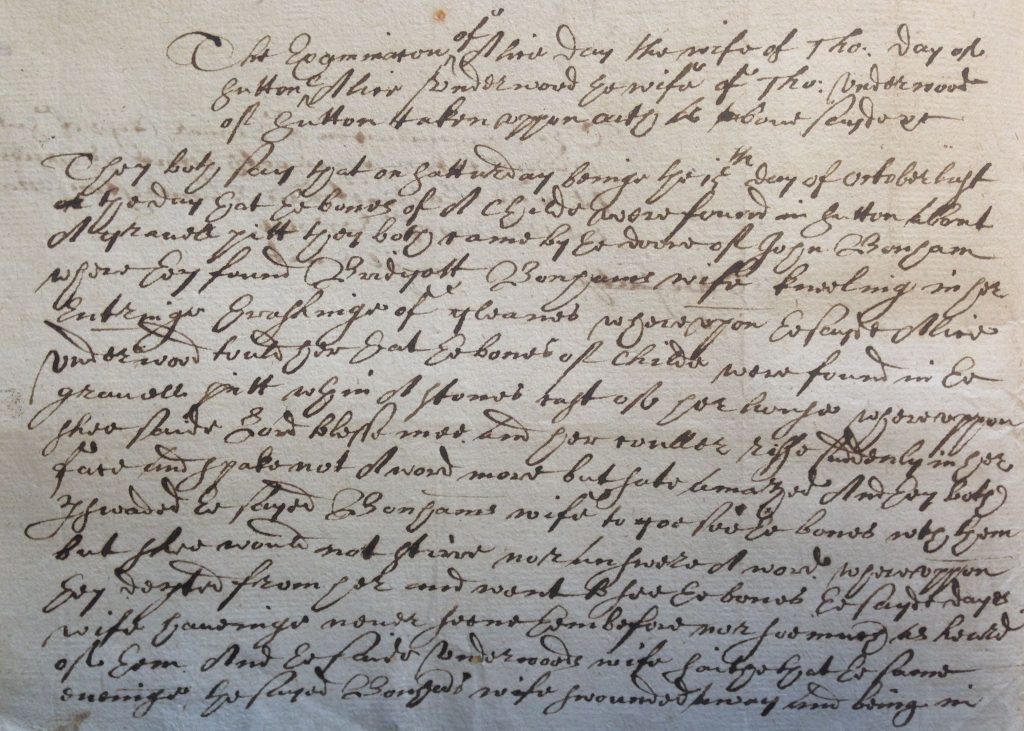

‘… her couller risse suddenly in her face and spake not a word more but sate amazed …’

Another deponent, Alice Daye, provided a telling insight into the reaction of Bridget Bonham at the news of the discovery of the pot. Daye claimed Bridget’s ‘colour [rose] suddenly in her face and [she] spoke not a word more but sat amazed.’ Daye continued that shortly after this Bridget Bonham ‘swooned away’. The testimony of Margaret Hammond confirmed Alice Daye’s account as she too stated she had found Bridget Bonham in a swoon. In a macabre twist, some local women left a thigh bone outside the door of the Bonham’s house. Mary Paufryman reported that Bridget had protested that the bone in question was comparable in size to her own thigh bone and so could not be that of a child.

Several of the depositions comprise the kind of detail one might typically associate with modern investigative practice. William Bradshaw, for example, who discovered the pot in the gravel pit was able to describe the site as ‘a short grave fit for a child […] not above a foot and a half deep’ and speculated it was dug in haste. Richard Springe, the parish grave-digger, similarly speculated that the grave was not very old given the state of decay of the bones. John Linwood, a constable, was charged with examining the ‘church book’ [parish register] at Sutton and determined that John Bonham junior was baptised in 1616 and would have been 11 years old at the time of his disappearance. A number of the deponents speculated on the size of the bones and whether they could be that of a young boy.

‘ … sayd he were as good goe seek for a needle in a bottle of hay as goe seek for his childe now …’

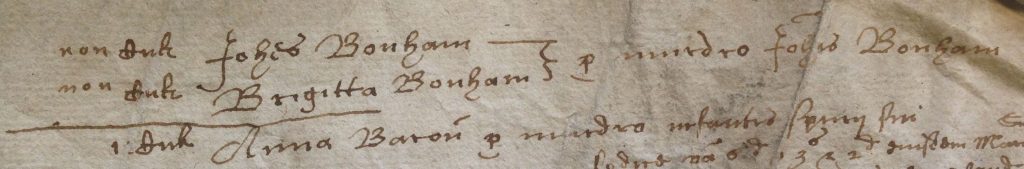

John and Bridget Bonham were tried for the murder of John Bonham junior. No full record exists of the court proceeding or of the verdict but it seems likely that the Bonhams were acquitted. The couple remained in Sutton and next appear in the assize records in 1647, accused of witchcraft, part of a wider witchcraft craze in East Anglia in the mid-1640s instigated by Matthew Hopkins, the self-proclaimed ‘Witchfinder-General’.

The 1636 depositions are a prime example of the research potential of the Isle of Ely assize records. The case of the Bonhams of Sutton, with its fulsome description and rich detail, is of interest to local and family historians as well as to those researching patterns of crime, criminal investigation and legal process in early-modern England. A project generously funded by the Cambridgeshire Family History Society is currently underway to catalogue the records of the Isle of Ely assizes. The project’s aim is to produce a full catalogue of these records for the first time and to highlight some of the most interesting cases.

Notes

With many thanks to Gill Shapland, stalwart volunteer and member of the Cambridgeshire Family History Society, for identifying this case, transcribing the depositions and providing background information on the Bonhams from the Sutton parish registers.

The Bonhams are referenced in several academic works, with a particular emphasis on the 1647 witchcraft accusation. See, in particular, Malcolm Gaskill, Crime and Mentalities in Early Modern England (Cambridge, 2000), pp. 259-60, and Malcom Gaskill, ‘Witchcraft and power in early modern England: the case of Margaret Moore’ in Women, Crime and the Courts, ed. J. Kermode and G. Walker (London, 1994), pp. 139-140.

I am writing about this very case, and I am wondering if Gill Shapland’s transcriptions have been published, and if not, how they might be accessed.

This sounds very interesting, Lucy. I have just sent you an email with contact details. We would be very interested to see your work when it’s published.