The Polonsky Foundation Greek Manuscripts Project: The conservators’ challenge – Part 2

Since conservation’s last post we have been very busy. We have continued to work on the Cambridge University Library material, have completed work on Christ’s, Pembroke and Sidney Sussex Colleges’ manuscripts and started work on St. John’s College manuscripts. As well as all of this we have been focussing on the in-depth conservation projects that we introduced in The conservators’ challenge – Part 1 – in this post we will update you on their treatment progress.

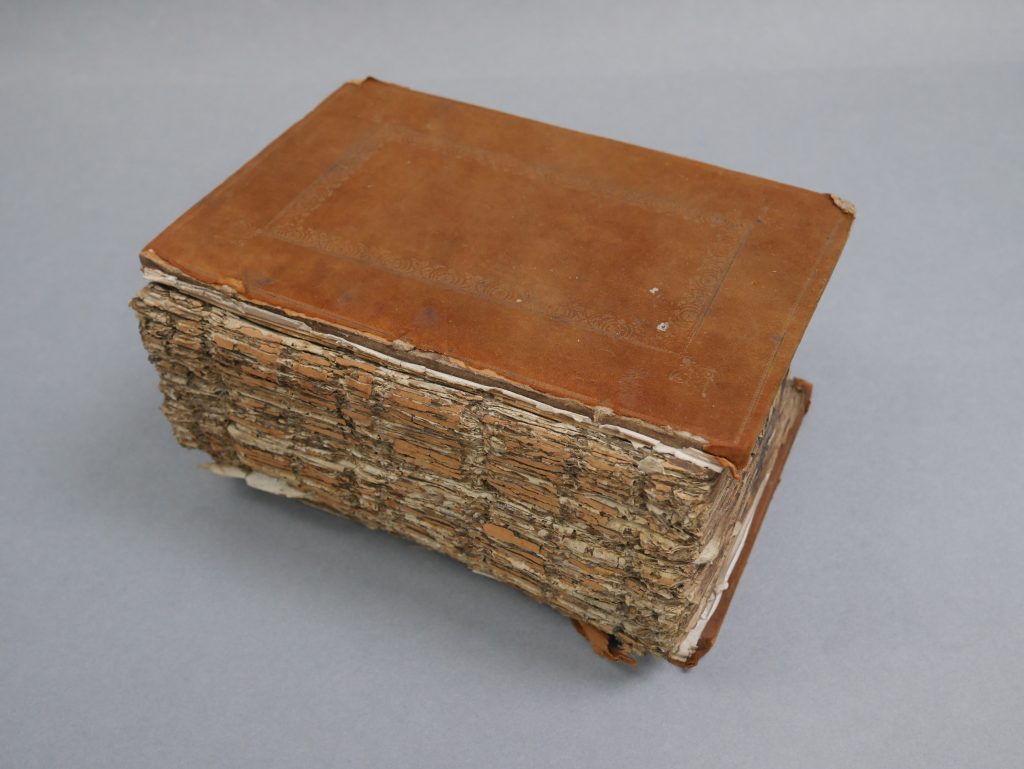

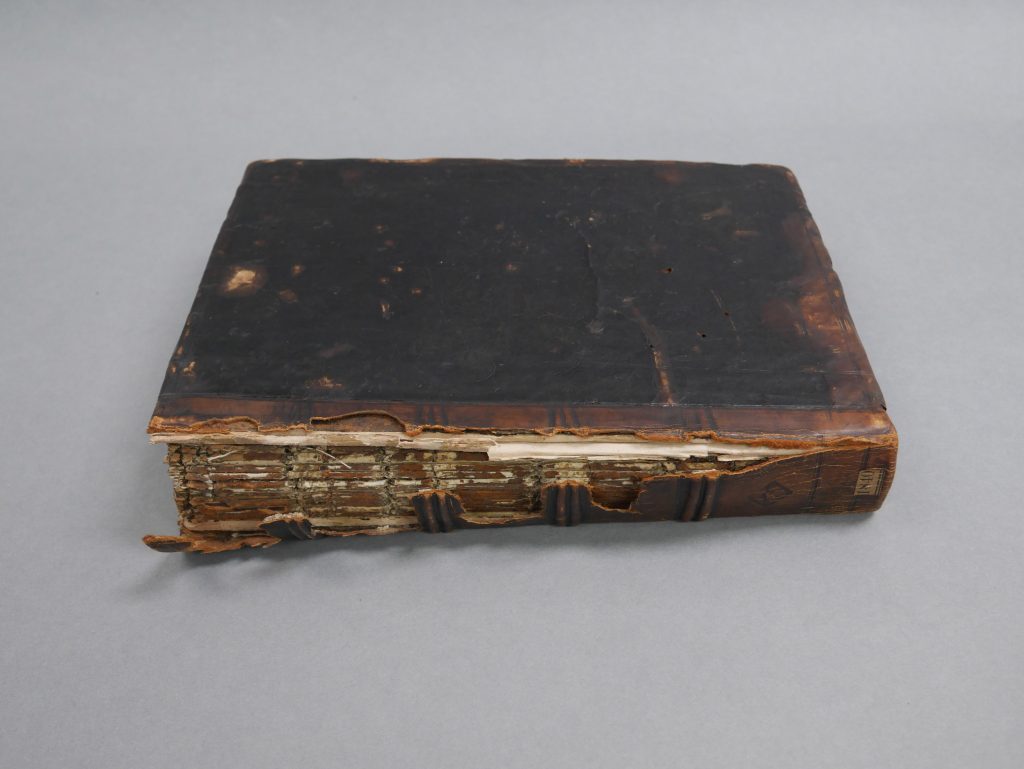

First, we will discuss the initial treatment of CUL Dd.4.39. As you may remember CUL MS Dd.4.39 is an 11th-century psalter which includes canticles and prayers. On arrival at the conservation studio the manuscript was in a post-medieval Northern European binding covered in brown reversed tanned skin. The manuscript consists of 364 parchment folios. Various elements of the original text are missing, though some have been replaced with folios from a later manuscript. No sewing structure remained, other than helical sewn spine-fold repairs. The parchment textblock has suffered heavily from cockling, abrasion, tears and losses. This left a lot of work for the conservators to do to make this manuscript stable once more.

As the textblock was completely detached, the binding was simply removed which meant cleaning and repair of the parchment textblock could start immediately. The first stage involved cleaning the leaves with a soft brush and smoke sponge. The second stage involved removing the hard and brittle animal glue and leather remnants from the spine-folds. In the current structure, the animal glue formed the attachment to the binding along with the endleaves. The glue was removed either mechanically or by using a wheat starch paste poultice which softened the glue so that it could be removed carefully using a spatula.

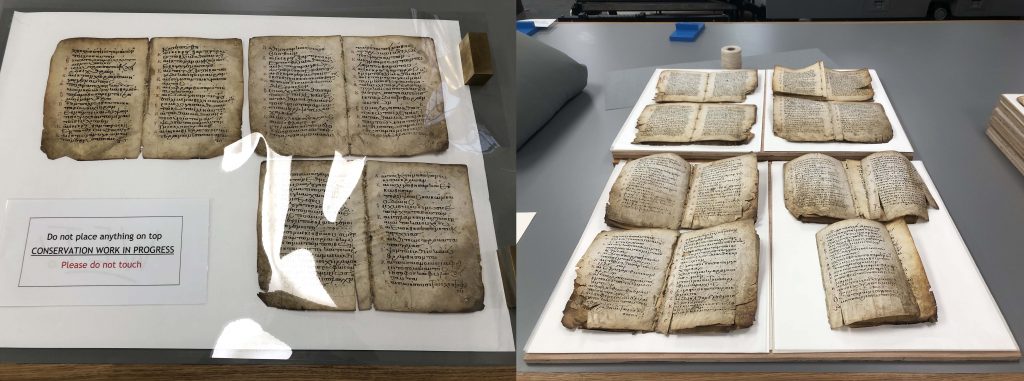

After cleaning, the conservators could humidify and relax the stiff and cockled parchment. Introducing moisture to the parchment in the form of vapour allowed the parchment to relax and the cockling in the parchment could be removed by drying the leaves under light weights. This resulted in a less brittle, softer parchment with fewer undulations, allowing the conservators to repair the parchment more effectively.

The repairs were carried out using toned Japanese paper adhered with wheat starch paste. This method was chosen due to the amount of repair that was required. Japanese paper can be very fine and very strong; using strong thin paper allowed the conservators to reduce the ‘bulk’ that may appear if many repairs were conducted in the same area of the textblock. Excessive bulk would affect the mechanics of the book once bound. Other benefits of using Japanese paper for repair is that it can be easily toned to match the parchment’s tone and repairs are quick to do!

Many of the repairs to the textblock of CUL MS Dd.4.39 were conducted along the spine-folds and the fore-edge bottom corner of the leaves. The spine-folds had been damaged through various rebindings and the application of hot animal glue. The fore-edge bottom corner had suffered most from losses, this damage was probably the result of the effects of water damage at some point in the manuscript’s life. The repaired manuscript is now ready for sewing.

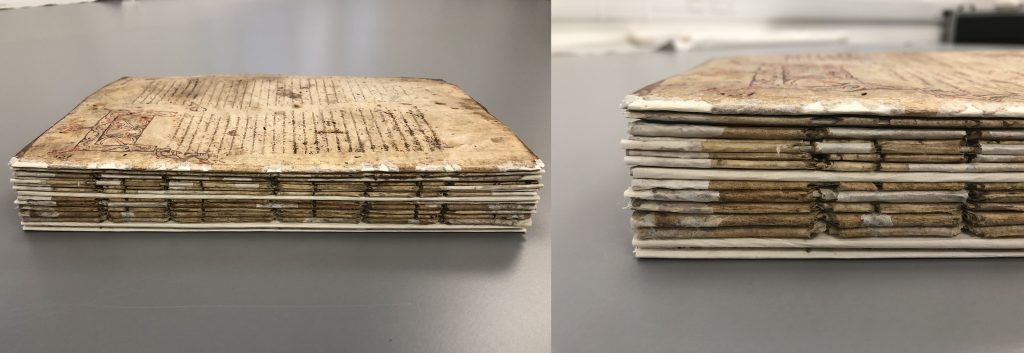

Our next manuscript, CUL MS Add.1840 has been through the same stages of treatment as CUL MS Dd.4.39 but with some differences, though the textblock was in much better condition.

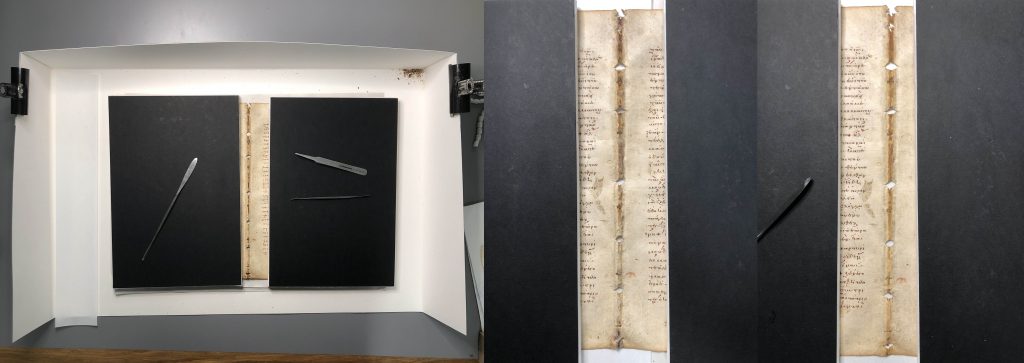

CUL MS Add.1840 is a 12th/13th century Evangelion (gospel book). The manuscript consists of 112 parchment folios that are completely detached from the binding. No sewing structure remains, though both V-cut and sawn-in sewing preparations from previous structures can be identified. The textblock has suffered from abrasion, insect damage, tears, losses and splits along the spine-folds.

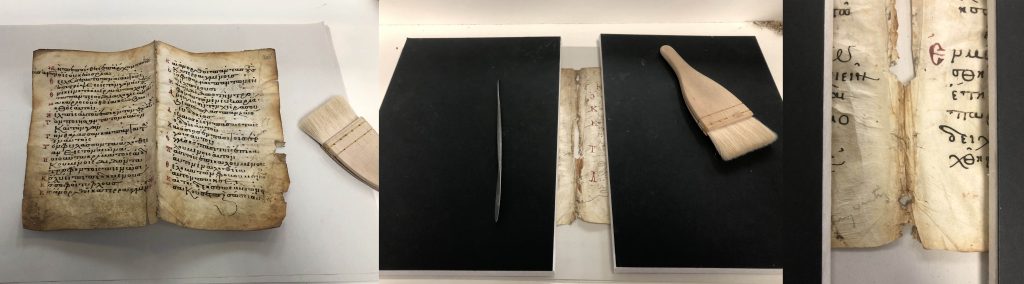

The textblock was simply removed from the detached binding, then the leaves were cleaned using a soft brush and smoke sponge. The dry and brittle animal glue was either removed mechanically or softened using a wheat starch paste poultice and removed carefully with a small spatula.

Once the whole textblock was clean, the conservators could locally humidify areas of the textblock where it was required. This was conducted where pleats and folds obscured text or prevented repair. In many cases the spine-folds had become acute and hard; humidifying allowed conservators to relax the fold, in turn, this would allow for a better repair.

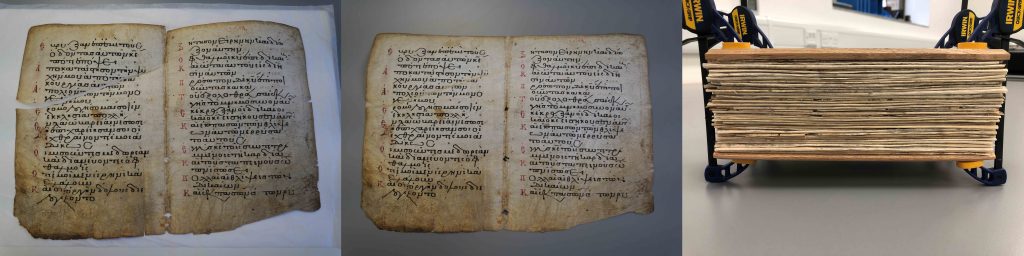

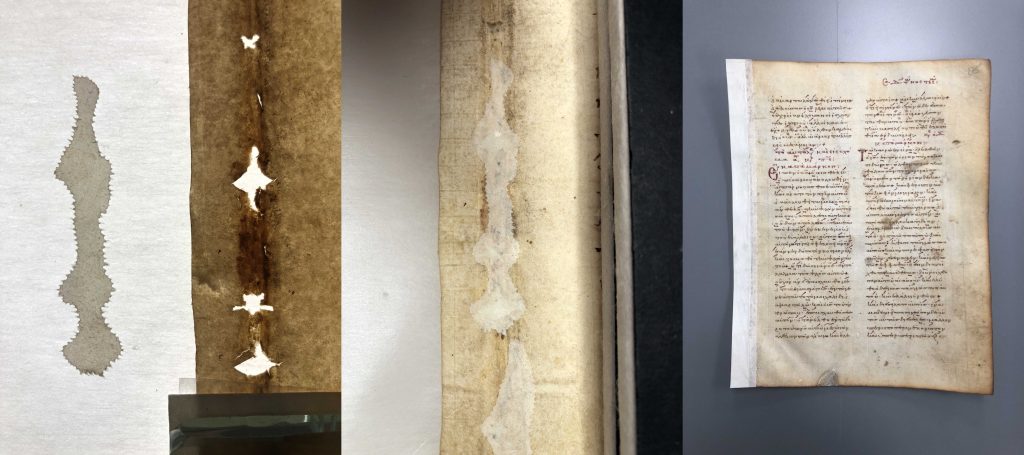

Repairs were carried out using caecum. Caecum is the dried lower intestine of a cow; it is a very fine material and comes in three thickness that can also be layered. Both caecum and parchment are animal products and so caecum is a sympathetic repair material; it will react in a similar way to parchment during changes of temperature and relative humidity. The adhesive used to adhere the repairs was a cold gelatine mousse.

The caecum is first cut to the correct shape, the edges are ‘feathered’ so that there are no hard, straight lines. Gelatine mousse is then applied to the caecum, the repair is put into place and then the repair is dried under a light weight.

Most of the repairs for CUL MS Add.1840 were conducted along the spine-folds. The damage had been caused by the previous rebindings and the hot glue that had been applied to the spine and at points penetrated the parchment. Now fully repaired the textblock is ready for resewing.

Our other in-depth project CUL MS Add.3048 is waiting to be started. As soon as we have any more progress to report, on any of the manuscripts, we will be sharing on Instagram, Twitter and of course here on the blog! Until next time!