Rank rogues and errant thieves: slander and defamation in the Isle of Ely

… ‘base beggarly rogue’, ‘false perjurer’, ‘knave and rascal’, ‘errant thief’, ‘pick-pocket, cheating whore and cut-purse’, ‘forsworn man’, ‘witch’, ‘night-walker’, ‘rank rogue’ …

At first glance the insults listed above may have been lifted directly from one of Shakespeare’s plays. They are instead some of the very real words which are recorded in slander and defamation cases in the Isle of Ely assize courts.

Slander, particularly that of a sexual or moral nature, was typically the chief business of the church courts in England. However, from the sixteenth century on, secular courts such as the assizes dealt with an increasing number of cases of slander and defamation of character. The reason for this was largely an economic one. While the words listed above appear, at least to the modern ear, to be archaic and relatively harmless, there was increased concern with the use of opprobrious, vexatious and disparaging words to cause injury to an individual’s reputation or livelihood. English common law was concerned less with the nature of the insults themselves as with the perceived financial damage caused. If an individual was able to demonstrate solid financial loss – for example, the loss of trade or customers – he or she could be compensated. Unlike the church courts which could only really offer penance as a form of recompense, the secular courts could award cash damages in cases of slander and defamation.

In his seminal work on church courts, Martin Ingram examined the cases of slander and defamation in the Isle of Ely assizes between 1571 and 1639.i His analysis showed that most cases were concerned with secular crimes, particularly accusations of theft, fraud and perjury. Comparatively few cases in this period relate to sexual or moral behaviour, such as accusations of bastardy, fornication, rape or witchcraft. Here are some typical examples:

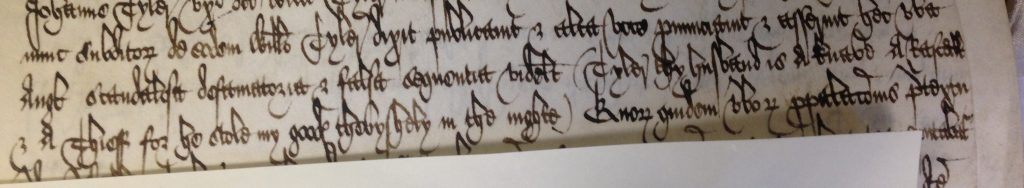

‘Tyler, your husband, is a knave, a rascal and a thief for he stole my goods thievishly in the night’: John Webbe of Thetford to Joan Tyler, 1580.

‘You are a thief and you get your living with thieving and stealing’: Richard Greene of Elm to William Mann, 1623.

‘John Jefferson is a forsworn and perjured knave and did forswear himself in laying out the Moe Fen [Mow Fen] ditch in Littleport and in saying my ditch was ditched’: David Smith of Littleport to John Jefferson, 1636.

‘[Richard and Margaret] are thieves and stole my ducks and made pies of them and sent them into the field to your workfolks’: Elizabeth Parker of Whittlesey to Richard and Margaret Cole, 1668.

In all these examples, the law was concerned with the loss of reputation or standing suffered by an individual rather than the actual words spoken.

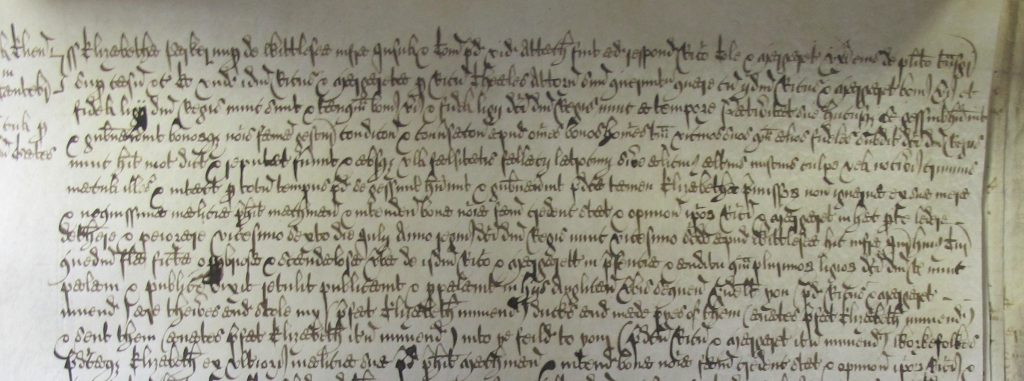

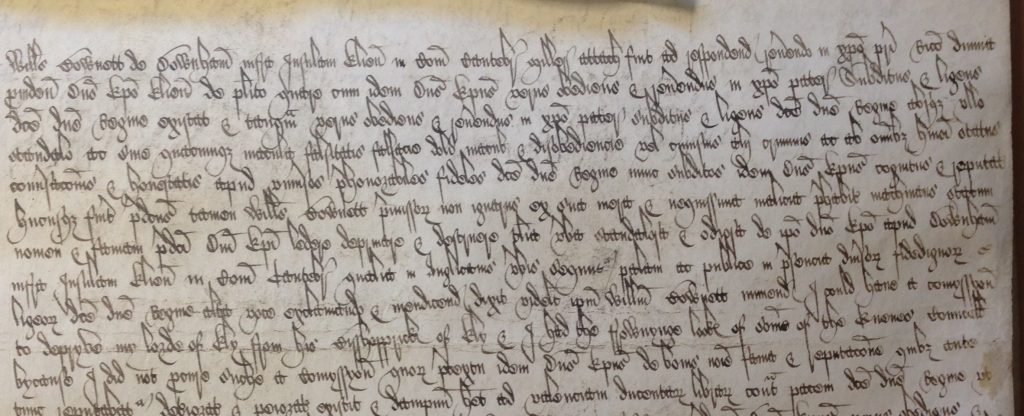

The preponderance of slander and defamation cases in the assizes also undoubtedly reflects long-standing grudges and tensions in local communities. There is evidence of one such feud between William Bownett, a miller of Downham, and Richard Cox, the Bishop of Ely, in the mid-1570s. Bownett appeared in defamation case in 1574 accused of threatening the Bishop. His recorded words were, ‘I could have a commission to deprive my Lord of Ely from his bishopric of Ely […]’. Later that year he appeared again accused of making false statements against the Bishop, the Duke of Norfolk and Queen Elizabeth. Further investigation reveals litigation between Richard Cox and Bownett (and others) relating to property in Cambridgeshire in the Court of Chancery and the Court of Star Chamber.

Here is a small selection of some of the more interesting cases in the Isle of Ely assizes:

‘You are a base beggarly rogue not worth a groat. You bid me to break fast and set poison before me to eat and would have poisoned me’: John Chambers to Edmund Homes, 1632.

‘You are a pick-pocket, a cheating whore and a cut-purse and keep a thievish house and a whore-house to entertain rogues and cut-purses, whores and thieves, and I will prove it’: Ellen Glendennell to Isabelle Wilson, 1645.

‘Catherine is a witch and has witched my cattle to death and if I had not looked out for it you would have witched me and all the ever I have’: William Boston to Catherine Middl[e]ton, 1607.

‘You are a false perjurer and deserve to have your ears nailed on the pillory’: John Robson to James Waldo, 1584.

‘There were certain geese stolen and eaten in your house and you were a partner in the stealing of them’: Adam Robbynson to Thomas Reyment, 1611.

‘[…] a thief, an errant thief and as errant a thief as any within the Isle’: Richard Crosley to Philip Axey, 1608.

It is difficult to draw a meaningful conclusion about the success or otherwise of slander cases in the assizes. Very few cases include a clear outcome; the entry is either incomplete or the case rolls over to the next session and then simply disappears from the records. The issue of compensation is similarly unclear. The sums claimed by plaintiffs appear extraordinary. Richard and Margaret Cole, for example, claimed £40 in damages while £200 was claimed in the case against William Bownett. As the entries, on the whole, do not state the final sum for damages, it is impossible to know if these figures reflect a true estimate of the financial injury incurred or if they were deliberately inflated. Whatever the case, the sheer volume and persistence of cases of slander and defamation in the assizes surely speaks volumes of the desire of ordinary people to use the court system to seek recompense.

A project funded by the Cambridgeshire Family History Society is currently underway to catalogue in detail the records of the Isle of Ely assizes. Further updates on the progress of the project will appear on this blog.

_________________________________________

i Martin Ingram, Church courts, sex and marriage in England, 1570-1640 (Cambridge, 1990), pp. 297-8.