Coping with isolation: Ernest Shackleton & the Cambridge University Press publication of the Encyclopaedia Britannica

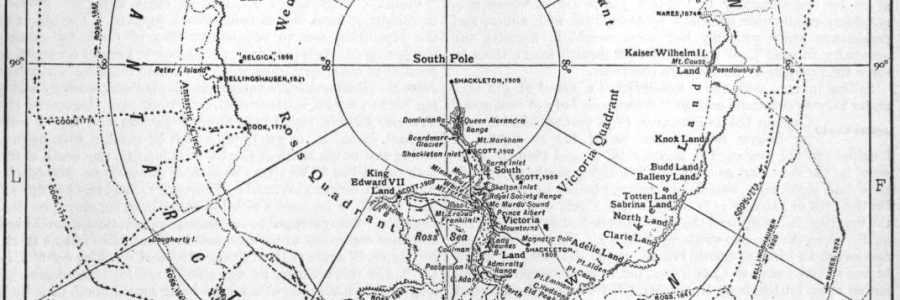

Given permission to depart in a telegram from the Admiralty with the single word ‘Proceed’, the Endurance sailed from Plymouth on 8 August 1914 to begin Ernest Shackleton’s attempt to walk from one side of the Antarctic continent to the other. The North and South Poles had been reached so this was the last great Antarctic prize. On his cabin shelves he stored a complete set of the 11th edition Encyclopaedia Britannica published by Cambridge University Press. There are many parallels from this remarkable story to our current days of isolation. Often funny, frequently moving, always inspiring, here are lessons we might draw from history …

Thwarted travel plans

Many of us will have booked tickets and accommodation for adventures far from home, but few can have spent over a year sweet-talking bankers, philanthropists and wealthy heiresses into funding our expeditions. When the Endurance became trapped in sea ice in January 1915 the crew of 28 sailors and explorers spent 9 months drifting away from their destination with the prevailing north-westerly currents of the Weddell Sea. They had been so close – in sight of land on 19 January – but on 27 October the Endurance was abandoned, crushed beyond repair by the unforgiving ice. This was the end of Shackleton’s dream. However great his personal disappointment, he showed resolve to his team. Alexander Macklin wrote ‘he shewed it neither in word or manner … without emotion, melodrama or excitement [he] said “Ship and stores have gone – so now we’ll go home.”’

Monotony of diet and food shortages

If you are finding out-of-date food stocks surprisingly edible and are managing to eat frequent variations of the same dish, spare a thought for the men living on ‘a sheet of ice floating on unfathomed seas.’ With supplies rescued from the sinking Endurance and catching the resident Antarctic fauna, ‘our supply of food was a cause of perpetual anxiety … our meals had to consist mainly of seal and penguin.’ Ever ingenious, Shackleton ‘continually rearranged the weekly menu’ believing that anticipation and surprise gave ‘a sort of mental speculation.’ The expedition cook, Charles Green was a trained baker and pastry chef. When onboard, he had cooked 4 meals and 12 loaves of bread a day, and he managed to celebrate New Year’s Day with ‘Dinner of pancake made from flour and water fried in seal blubber. Supper stewed seal meat and cocoa.’ Showing great resourcefulness, he turned his hand to making stew called ‘hoosh’ from seal, penguin, limpets and seaweed. One striking similarity is the eventual shortage of flour, expressed with eloquence and understatement by Shackleton ‘We were, of course, very short of the farinaceous element in our diet.’

Exercise and learning

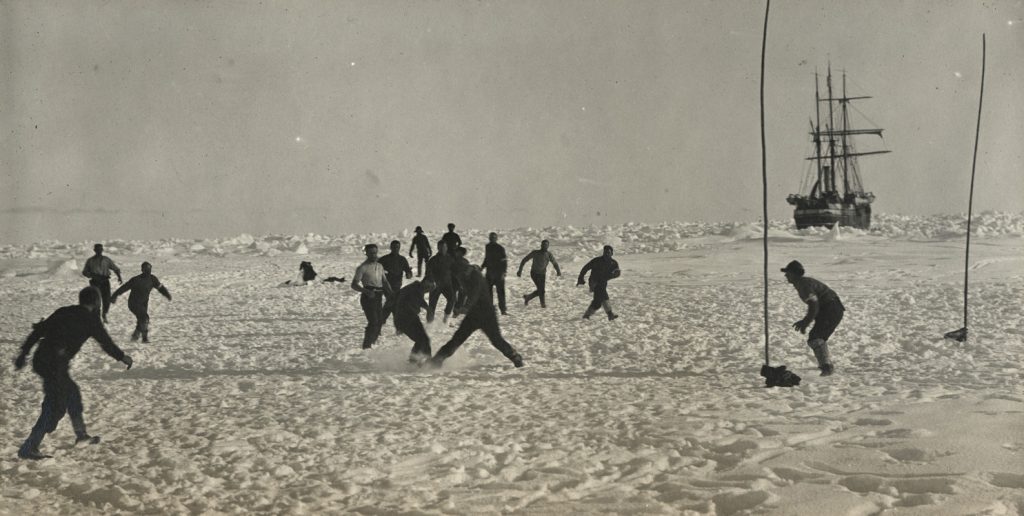

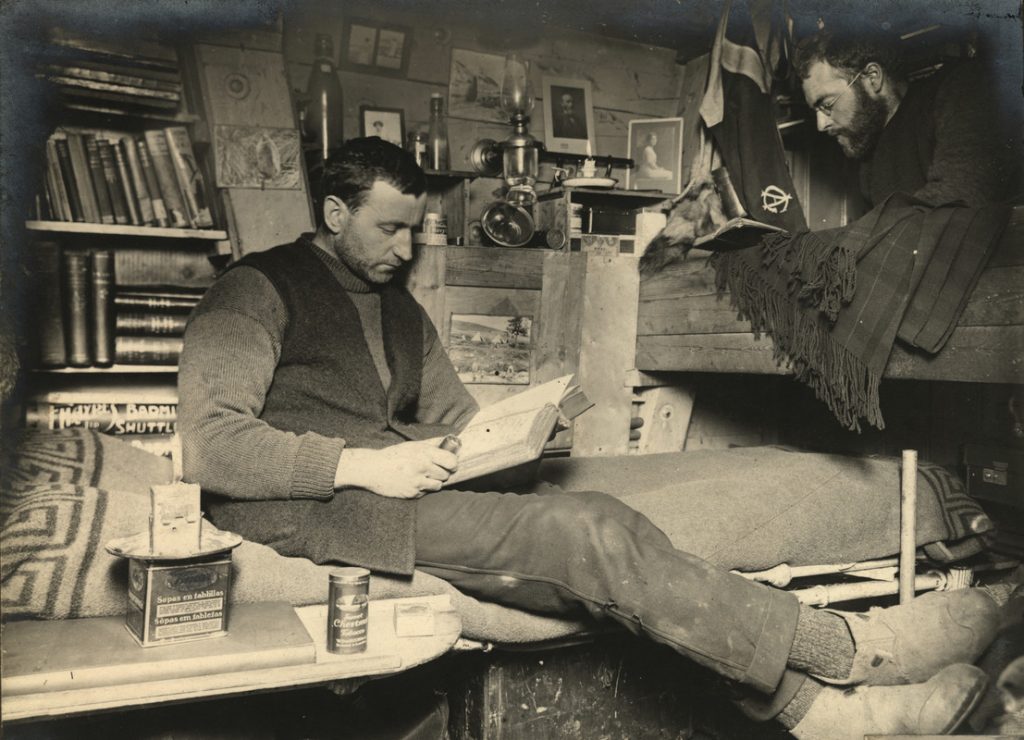

Joe Wicks realised quickly the importance of physical exercise in times of stress and isolation. The many galleries, theatres, publishers including the Press, which responded to the emergency by making content available online, recognised the value of mental stimulation. So too did Ernest Shackleton. He had taken the 11th edition Encyclopaedia Britannica published by Cambridge University Press in 1910-11 on board the Endurance, on the ice, and on the boats to Elephant Island to keep the academic minds engaged, to provide a course of education for sailors who had left school at a young age, and to ‘settle our many arguments.’ Regular games of football and hockey on the ice kept men fit and warm in sub-zero temperatures.

Walking the dogs

Anyone who has a dog, or wishes they had adopted a puppy earlier in the year, will appreciate the opportunities they offer for entertainment and exercise. 69 Canadian sledge dogs had joined the Endurance in Buenos Aires, living in kennels running the length of the ship, and later in ‘dogloos’ on the ice. Their original purpose had been to pull supplies during the march across the continent, and they became vital to the retrieval of equipment and food from Dump Camp to the longer-term Ocean Camp. To while away the monotonous days, sledging races became highly competitive and a daily routine of exercise for the dogs provided the men with much-needed diversion. ‘Runs with the dogs and vigorous games of hockey and football on the rough, snow-covered floe kept all hands in good condition,’ wrote Ernest Shackleton proudly.

New communication technology

Microsoft Teams, Zoom, Google Meet … to some of us these are new communication technologies, learned rapidly and reaping rewards in bridging the information and friendship gaps. The Endurance carried a wireless receiver but Shackleton had insufficient funds for a transmitting plant so the crew listened eagerly for wireless signals for contact with the outside world. It had been arranged that the wireless station on the Falkland Islands would send signals every month, but it was 1000 miles away and the distance was too great for any message to be received. During 22 months of monotony interspersed with extreme danger, some men did not hear voices other than those always within a few metres of themselves.

Coping with isolation

Frank Worsley, captain of the Endurance and outstanding navigator, wrote ‘I have experienced a good many strange things in my time, but this situation of detachment from the living world was one of the most memorable.’ Shackleton was keenly aware of the wellbeing of his team, showing special concern for the shy and less-vocal men. Alexander Macklin wrote that Shackleton, nicknamed the Boss, ‘had a nice way of, every now and then, when he came across you by yourself, getting into conversation and talking to you.’ Green, the cook under great pressure to provide nutritious meals, told Shackleton’s early biographer James Fisher that one day ‘I was crying my eyes out. I was absolutely done … The Boss turned up, asking how I was getting on. “Oh, all right,” I said. He said, “What are you going to do with all the money when you get home?”

Medics and their textbooks

The Press released textbooks to medical students early in the pandemic, a gesture which was both practical and morale-boosting. Two surgeons on the expedition, Alexander Macklin and James McIlroy, took constant care of the medical and dental health of the crew, relying on the Encyclopaedia Britannica for the latest information about scurvy. When frostbite on the toes of the young stowaway Perce Blackborow required amputation, the surgeons relied on the ‘Mortification’ section of the Encyclopaedia for guidance on where to operate.

Differences of opinion

Extended confinement with strong-willed individuals brings a range of unforeseen challenges. One of these may be a shift in responsibilities for household duties. The author of the most acerbic and entertaining diary of the expedition was former Royal Marine, Captain Thomas Orde-Lees. Unaccustomed to Shackleton’s policy of equality, he wrote ‘I simply hate scrubbing. I am able to put aside pride of caste in most things but I must say that I think scrubbing floors is not fair work for people who have been brought up in refinement.’ He noted that although ‘most members are what one might term rather definite personalities […] there is no real need to have quarrels of any kind with one’s comrades,’ thereby rising above a recent incident in which a handful of lentils had been dropped into his open mouth whilst sleeping to stop his snoring. Isolated for months on desolate Elephant Island, however, tension broke out and Orde-Lees challenged Macklin to a duel at dawn on the beach with broken oars as weapons. Recalling the non-stop trek over South Georgia, the lack of sleep and the constant danger of falling into a crevasse, Frank Worsley made a comment that is worth bearing in mind during any domestic irritation: ‘We treated each other with a good deal more consideration than we should have done in normal circumstances. Never is etiquette and “good form” observed more carefully than by experienced travellers when they find themselves in a tight place.’

Haircut problems

If anyone is considering, or has suffered, the discomfort of home haircuts, again Shackleton was there before us. To give the crew a laugh, he organised a team hair cut with Lewis Rickinson, the First Engineer, cutting Shackleton’s hair ‘till not a vestige of hair [was] left.’ Frank Hurley took a photograph when all the crew had joined in and looked ‘like convicts.’

Small gestures

Birthdays without parties, unable to offer a consoling hug to friends, Mother’s Day shared at a distance without an offering of flowers, the efforts we make to show compassion and caring are difficult in these days. Expecting to be alone on Elephant Island for 2 weeks whilst Shackleton crossed the southern Atlantic in the tiny James Caird lifeboat, then walked across the uncharted mountains of South Georgia for help, 22 men were left for 4 ½ months until they were rescued. In these months, the quiet Cambridge physicist Reginald James kept his mental balance by working on the geometry problems in the Encyclopaedia Britannica and writing his journal. One of the most touching gestures of this desperate situation was the gift of a pencil from the expedition photographer Frank Hurley to Reginald James. It was just one small pencil but it could open world of self-expression.

The toilet paper problem

Meredith Hooper wrote eloquently about the connection between the Press publication of the Encyclopaedia Britannica and the Endurance expedition as part of the centenary celebrations in 2014. She curated an exhibition in the Press Museum and recorded her recollections of purchasing her copy of the 11th edition Encyclopaedia, which she termed ‘the internet before the internet.’ Of all the fascinating discoveries made during research in archives across the world, the detail picked up in the international press was her sentence “On Endurance [the pages of the Encyclopaedia] were being ripped up because paper was good for lighting pipes and probably good for other things, although they don’t say it [in their diaries].’ This translated into a news flurry with a typical headline in The Australian newspaper dated 21 November 2014 ‘Ernest Shackleton used encyclopedias as toilet paper in Antarctic.’

Three cheers

It is incredible how emotional one can become when joining the British cheer at 8pm on Thursdays. As an expression of support for NHS staff and carers, it is a visible and audible expression of thanks. It is also an expression of community support with residents coming out of their houses to see neighbours from a distance, and a release of pent-up energy. On a few key moments during their ordeal, the expedition members gave similar cheers to voice their good spirits. When Shackleton left on the rescue mission in the James Caird the 22 men left behind on a bleak, snow-covered island ‘gave three hearty cheers.’ When, after several failed attempts trying to break through the ice surrounding Elephant Island, finally the small Chilean tug steamer the Yelcho arrived in view, Will Bakewell wrote ‘Then there was some real live cheers given.’

‘All well’

Sending messages to friends and family, perhaps not contacted for a while, and receiving a reply confirming that everyone is well, brings strong feelings of relief. The question ‘all well?’ has its echo in Shackleton’s return to Elephant Island on 30 August 1916 finding all men close to starvation but alive. So sparse an exchange, yet telling such a tale of isolation, bravery and endurance …

‘Are you all well?’

‘All safe, all well.’

By Dr Rosalind Grooms (Cambridge University Press Archivist)

References, further reading and viewing:

Anyone wishing to use images featured in this blog should first refer to the SPRI Picture Library.

The Endurance: Shackleton’s Legendary Antarctic Expedition by Caroline Alexander (Bloomsbury 1998)

South: The Story of Shackleton’s Last Expedition 1914-17 by Ernest Shackleton edited by Peter King (Pimlico 1999)

Shackleton’s Way: Leadership Lessons from the Great Antarctic Explorer by Margot Morrell and Stephanie Capparell (Nicholas Brealey Publishing 2011)

Cambridge University Press Museum https://www.cambridge.org/about-us/who-we-are/history/press-museum/greatest-treasure-library/

Scott Polar Research Institute https://www.spri.cam.ac.uk/museum/shackleton/

Royal Geographical Society Enduring Eye: The Antarctic Legacy of Sir Ernest Shackleton and Frank Hurley exhibition online https://www.rgs.org/about/our-collections/enduring-eye/

DVD Shackleton with Kenneth Branagh (2008)

DVD South directed by Frank Hurley (1919)