‘I dared not dream that this dream had come true’: musings on special collections in lockdown

I dared not dream that this dream had come true:

Charles Hanson Towne: ‘On first looking into the manuscript of Endymion‘ (1915)

That I was bending over that yellow page

Lit with his words – our boy, our poet, our sage –

And that I touched the parchment, old yet new,

Whereon his fingers has been. I grew

Strangely afraid, as if some heritage

Of wonder from a distant, holy age

Had suddenly fallen on me, like soft dew.

Before working in Cambridge I had seen few medieval manuscripts. Once as a boy, ten maybe, I visited an exhibition of them with my Mum at Manchester’s John Rylands Library. I remember not one word of the panel text or manuscript labels. Yet the luminosity of those illuminations – something that comes only with age and craftmanship – still flickers in my eye. Now I see ancient manuscripts and rare books all the time, with all the privileges of doing so outside a glass case. Frequently, I am mesmerised. Upon requesting a volume by the teenage forger Thomas Chatterton, it transpired to have been once owned by William Blake. I sat in the reading room and read Chatterton, just as Blake might once have done. In manuscript form the seemingly mundane can have the power to move. The last exhibition I worked on contained a letter from Dame Rosemary Murray (instrumental in the foundation of New Hall, now Murray Edwards College): ‘Hurray, hourah, hurrah, hoorah how does one spell the word?’ she wrote to Robin Hammond on her appointment as the second fellow of New Hall. Murray would later become the first female Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge, and was known previously to me only through formal official portraits. But here emerged the personality of a much livelier character.

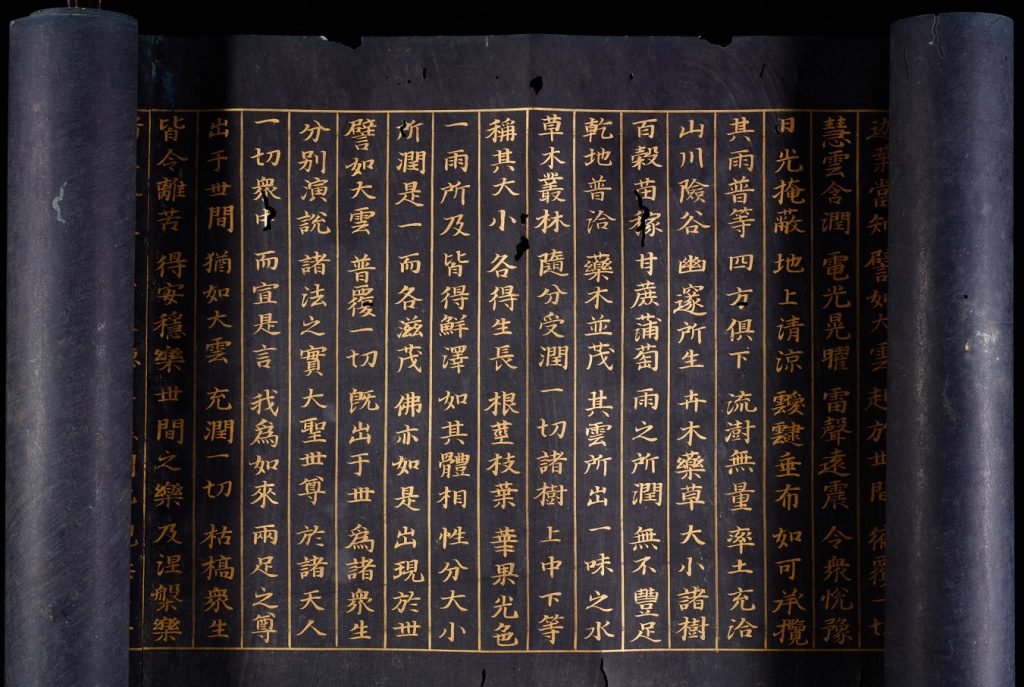

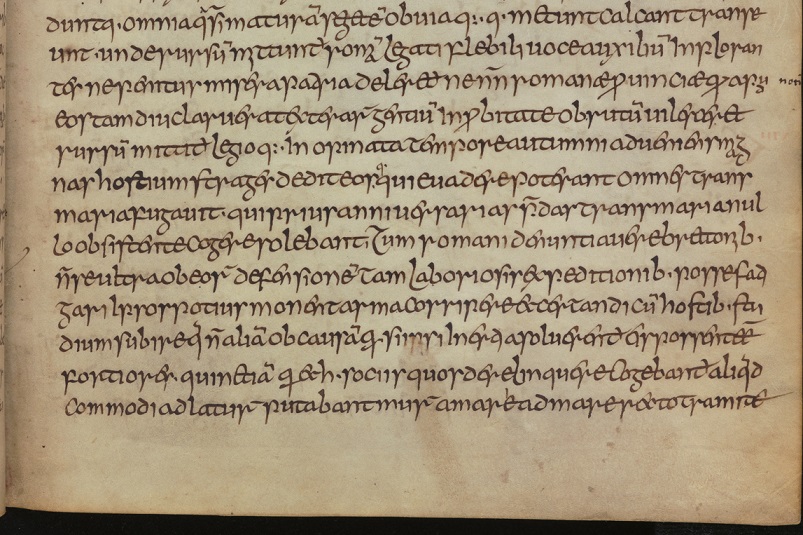

When planning exhibitions we get these items out, and we talk about them. And it is this I miss the most. To work in a library is to learn. What privilege to stand before a twelfth-century lotus sutra, deep blue in colour and exquisitely written in gold calligraphy, and discuss its production with the Head of the Japanese & Korean collections at the UL. To examine a letter written by Darwin and hear it interpreted by a scholar whose career has been devoted to understanding the man and his circle. An afternoon with the Head of the Genizah Research Unit, and the Keeper of Rare Books & Early Manuscripts exploring the transition of religious texts across temporal and physical space. And to do so with the most ancient of Biblical and Quranic texts laid out in front of you. ‘The birth of English literature’ was how the importance of the Moore Bede was articulated to me; at once I was transported.

In this pandemic we have gone digital, and it is magnificent and a triumph of human ingenuity. But I long for the physical. The collections of the UL were made by people, and are nothing without people. I want to feel again the ‘soft dew’ of a distant age, as Charles Hanson Towne did on seeing the manuscript of John Keats’s epic poem Endymion at the Morgan Library in New York. The collections at the UL remain accessible through the digital, while the physical collections lie waiting for their researchers, their keepers, their knowledge seekers, and those who revel in the actual. I dare not dream when we might see them again. Keats, like Towne, was moved by the power of being in the presence of tangible things. I think of the University Library collections as he thought of his Grecian urn…

When old age shall this generation waste

John Keats: Ode on a Grecian urn (1819)

Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe.

Dr Chris Burgess (Head of Exhibitions & Public Programmes)