Some Islamic manuscripts from Africa

In among the very varied items which constitute Library’s Islamic manuscript collection there is a small number of texts originating from the Saharan and sub-Saharan regions of Africa, including the Sudan and West Africa. Islam and Arabic learning reached these regions somewhere between the 9th and 13th centuries and, as a result, the population contains a large minority of indigenous Arabic speakers. In most of these regions, though Islam is widespread, Arabic is not the dominant language in daily use, most inhabitants would use one of the many indigenous African languages on a daily basis. These manuscripts are not particularly old, the majority appearing to date from the 18th to early 20th centuries. At this time Arabic was the language of communication among the literate and wealthier inhabitants who were those with both the skill and means to produce such manuscripts. These items are not shelved together but are scattered within the Library’s much more extensive collection of Islamic manuscripts, the vast majority of which originate from the wider Arabic-speaking world including the Arabian Peninsula, the Maghreb, Turkey, Iran and Mughal India.

These Islamic texts from Africa have certain physical attributes all of their own. They are not fine manuscripts made for use in the mosque or library, but workaday objects. They were produced for daily use and for traveling with their owners, and because of this, they have their own unique character and structure. Most are copies of well-known texts such as prayer-books or other religious compilations which their owners could use on a regular basis, to carry out their devotions. Other examples were scholarly texts copied and used by teachers in their own personal libraries. They were also passed between members of their learned community and who would also take them on their travels for teaching purposes. They were obviously much used, show signs of wear and tear, and often have a somewhat battered appearance. Examples of such texts from earlier centuries would be unlikely to have survived the climatic conditions and such heavy use.

One distinctive characteristic of these manuscripts is that they are written on single leaves of paper. This is not of a high quality and probably imported for this purpose from North Africa or Europe. These folios are unbound, generally held together by some form of cover or wrapping and tied around with string or leather straps. Some also have a specially made leather carrying satchel with decorative tooling. The text is written in black ink which has frequently faded to brown with the vocalization (vowel points) added in red ink. This form of Arabic script, with long curling descenders has its own unique style, but is likely to be descended from the ‘Maghribi’, style originating from North Africa and Andalusia and from which many cultural influences penetrated the region. Some of the manuscripts contain decorative motifs in red and black ink in the margins and chapter ends.

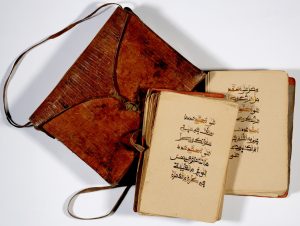

One interesting, and very characteristic example, is an early 20th century copy of the well-known prayer book, the Dalāʼil al-khayrāt, a ‘manual’ composed of blessings and prayers for everyday life and in particular for the pilgrimage to Mecca (Ms Or.2251). Partly composed of selections from the Qur`an and sayings of the prophet, the original work is attributed to the Sufi Muḥammad ibn Sulaymān al-Jazūlī (d. 1465 CE), who lived in in Morocco. It is the most popular work of Muslim devotion in Africa, used both for private prayer and meditation and for recitation at public festivals and ceremonies. This particular manuscript consisting of unbound leaves of yellowish-brown paper is held within two cardboard covers then tied together with a leather thong. The whole structure fits neatly into a brown leather satchel with a triangular flap and fastening loop. Though it has no illustrations, it does contain some decorative motifs drawn in red ink between texts and in the margins. It is evidently a much-used copy of the text and could easily be carried on the move by its owner to be easily accessible whenever needed.

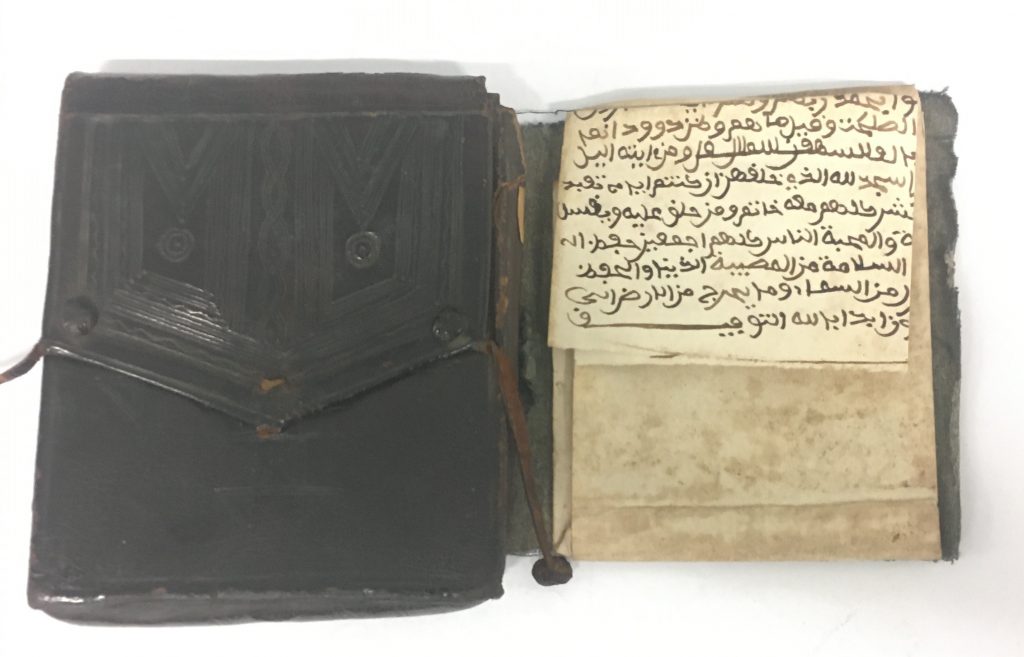

Another copy of Dalāʼil al-khayrāt, though smaller and squarer in shape is housed in a beautifully decorated dark brown leather satchel with leather detailing and fastening loop (Ms Add.3500). This manuscript was presented to the Library in 1898 by a Major Charles Jenkinson who also donated three other volumes including two other religious texts; an African prayer-book, the first portion of which begins with an account of the Rijal al-ghayb (Treatise on the invisible man) (Ms Add.3501). This also has a dark brown leather pouch with a flap. He also donated an anonymous manuscript containing traditions of the Prophet (Ms Add.3502), and a further volume of traditions of the Prophet rescued from the ruins of Bornu (now northeastern Nigeria) at a time of political unrest (Ms Add.3503).

These manuscripts did not arrive in the Library as part of large collections amassed by scholars or travelers, nor have they been purchased from manuscript dealers, as they are not of significant financial value. They all originate from single donors, such as Major Jenkinson, who were either scholars, military personnel, administrators, diplomats or missionaries in the region during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Any mention of particular places in the text or provenance is unusual but in addition to the mention of Bornu, another manuscript donated by a W.D. Webster in 1903 is annotated with the remark ‘from the Soudan’. It also has a dark brown leather pouch and flap and is a copy of an African manuscript with texts on the names of God and their virtues, magical squares and alchemy (Ms Or.413).

A manuscript donated by a Reverend Wilson in 1916 consists of 8 folios written in Arabic script but with prayers in an African language (Ms Or.954). Annotations or interlinear text in African languages are not uncommon and indicate the multi-cultural context in which these manuscripts originated. While the main body of text is in Arabic, the African copyists and authors often included extensive annotations in their own indigenous language.

In 1913, Sir Stephen Gaselee (1882-1943), better known for his generosity in donating his valuable collection of incunabula to the Library, also donated an African prayer-book in a dark brown leather satchel with fastening loop (Ms Or.891). A diplomat and man of eclectic tastes, he also presented the Library with its most ancient text, a Sumerian cuneiform tablet.

Since these manuscripts came to the library singly or in small numbers and were not seen at the time to be of great value, their recording and cataloguing has been brief and incomplete. But now these are available in the Fihrist on-line catalogue of Islamic manuscripts and one volume from the collection (Ms Or.2251) has been digitized and is available in the Cambridge Digital Library.

The range of materials, the structures and their decorative content, marks these manuscripts out as very different from the finely produced and often illuminated manuscripts from the Islamic world of the Middle East and for that reason they are especially interesting. This collection demonstrates that this region of Africa had a culture where education and learning through the written word was greatly valued. The region was not as isolated, as might be thought, and had many contacts with the wider world, especially from the Maghreb to the North across the Sahara. For all these reasons, it is very satisfying to re-examine and bring to light this rich collection, which deserves greater recognition and scholarly attention to unlock more of the secrets the manuscripts contain.

I shared the post with my daughter who formerly worked at the US Embassy in Mauritania. The ambassador at the time collected publications about that West African country, which contributed to her interest in traveling to some of the ancient libraries inland. Here is her comment to me: As for the books. Very interesting and she should go visit the libraries in Chinguetti. I don’t remember being shown leather satchelled books, but there were lots of interesting things. Probably early collectors in the region picked up the Islamic books, but there are science and math books and, interestingly, the libraries very proudly contain Bibles and Torahs and other readings bc (as we were told by one of the owners) a well-rounded scholar reads more than just their own religion.

Dear Caroline – Thanks for your comment. Anything more which add to knowledge about these collections is much appreciated and to know there were more texts than just religious ones is interesting too. This is an area which needs more research and to know more about libraries an collectors is fascinating.

Many thanks,

Catherine Ansorge