Cape Town Anti-Convict Petition, 1849

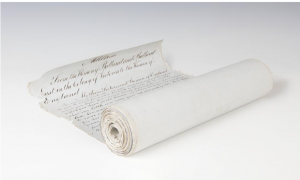

The Royal Commonwealth Society Department is delighted to announce that it has digitized one of the most fascinating items in its collection: a parchment roll from 1840s southern Africa, which measures more than 4.5 metres (15 feet) in length (RCMS 196). The roll documents one of the most dramatic political protests in the early history of Cape Colony, instigated by proposals to transport convicts there in 1847. As part of a reform of the British penal transportation system, convicts nearing the end of their sentences, ‘ticket of leave men,’ would be sent to complete their terms working in the colonies, and thereafter be free to settle or return to the United Kingdom. Secretary of State for the Colonies, Earl Grey, considered that the additional labour force might be welcome in Cape Colony and wrote to its governor, Sir Harry Smith, in 1848, broaching the idea and asking him to sound out opinion. Local reaction was vehemently opposed and Smith forwarded petitions rejecting the proposal. Unfortunately Grey went ahead without waiting, and on 4 September, the Cape was selected to receive ticket of leave men. On 8 February 1849, the ship Neptune sailed for Bermuda to land three hundred convicts and collect about the same number for transportation to the Cape.

On 21 March, the ‘Commercial Advertizer’ of Cape Town published news of the Neptune’s mission, a fact soon after confirmed by Smith, who had received dispatches with details of the new scheme. This incited a second wave of violent reaction against transportation, stimulated by anger that the colony’s original opposition apparently had been ignored. The newspaper’s editor, John Fairbairn, suggested that a strongly worded petition be drafted and placed in the Commercial Exchange for signature, and this is the document preserved by the RCS, signed by 450 people:

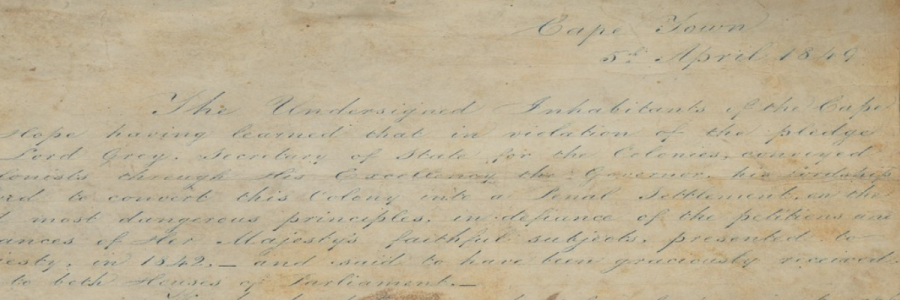

‘The Undersigned Inhabitants of the Cape of Good Hope having learned that in violation of the pledge given by

Lord Grey… His Lordship has resolved to convert this Colony into

a Penal Settlement, on the worst and most dangerous principles, in defiance of the petitions and remonstrances of Her Majesty’s faithful subjects, presented to Her Majesty, in 1842 – and said to have been graciously received – and also to both Houses of Parliament…

We hereby declare and solemnly promise to each other, and to all our fellow Colonists, that we will not employ in any capacity, or receive on any terms into our establishments, anyone of the Convicted Felons, whom the Secretary of State for the Colonies has ordered to be transported to our shores and turned loose among us, under the designation of ‘Exiles’, or Convicts holding Tickets of Leave.

And we hereby call upon His Excellency the Governor… to convey to Her Majesty, by the first opportunity, this expression of the grief, shame, and indignation with which this breach of faith, on the part of the Secretary for the Colonies, has filled every loyal heart.’

Public meetings mobilised political opinion against the scheme and a further wave of petitions were sent to the governor, who forwarded them to the UK, where they were printed in a Parliamentary Paper (31 January 1850). The RCS possesses Grey’s personal copy. An Anti-Convict Association was created, pledging to ‘discountance and drop connection with any person who may assist in landing, supporting or employing such convicted felons’ and branches spread throughout the colony. Official notification of the dispatch of the convicts arrived on 15 June and a great public meeting was held on 4 July, resulting in another petition to Smith, who promised not to land the unfortunate convicts, but declared that he could not send them away without authority from Grey. A tense stand-off ensued. Three citizens who accepted vacant seats on the Legislative Council were assaulted and burnt in effigy, and the Association’s pledge was enforced to refuse supplies to the government’s naval, military and civil departments.

The Neptune arrived in Simon’s Bay on 19 September. Notification from Grey that he had abandoned plans to send further convicts to Cape Colony arrived in December, and in February 1850 the Neptune was ordered to sail for Van Diemen’s Land. The Association then disbanded. The episode is a significant example of the power of popular protest and formed an important step in the Cape’s advance towards representative government. The RCS holds other important records relating to transportation and has digitised a similar anti-convict petition from the women of Ballarat, Australia, in 1864.

The Cape Town petition was presented to the RCS by Professor G.C. Moore-Smith, great-nephew of Sir Harry Smith, in 1920. It was digitised thanks to the generosity of a library grant from the Smuts Memorial Fund.

A fascinating document. I am writing a history of the life and times of Dr A J Tancred, a member of the first Cape Parliament. If he was at the Cape at this moment in time he would, being something of a populist and never passing by the chance to criticise the Governor in Cape Town, or the Colonial Office in London, have involved himself in this furore. Would it be possible for someone to search the 450 signatures to see if his name is amongst them? I am aware that he may have been in London at the time but as he did yo-yo between Cape Town and London at the time, I cannot be sure where he was. I am of course prepared to pay for researcher time looking at the document as appropriate. I am unable to get to Cambridge at present myself.

Dear Bernard,

When viewing the petition on Cambridge Digital Library, click on the icon with double arrows just to the left of the banner which reads ‘Home/ Royal Commonwealth Society…’ to get a full screen view. You can then zoom in to read the signatures.

All the best, John