Nineteenth-century dialect writing

In the first in a series of guest posts by UL researchers, Georgia Thurston (Faculty of English, University of Cambridge) shares her research towards a PhD on ‘Dialect and modernity in the nineteenth-century novel’)

Writing in dialect involves a curious combination of processes. It is equal parts recording and performing a regional identity through linguistic tropes and themes. The expansion of urban centres and the development of working-class print cultures led to an explosion of dialect novels, poems, and performances in the mid-nineteenth century. These dialect texts sold in the tens of thousands, and were considered as repositories of local experience and language. Although incredibly popular during the nineteenth century, many of the dialect writers who contributed to this English tradition have largely fallen out of cultural memory.

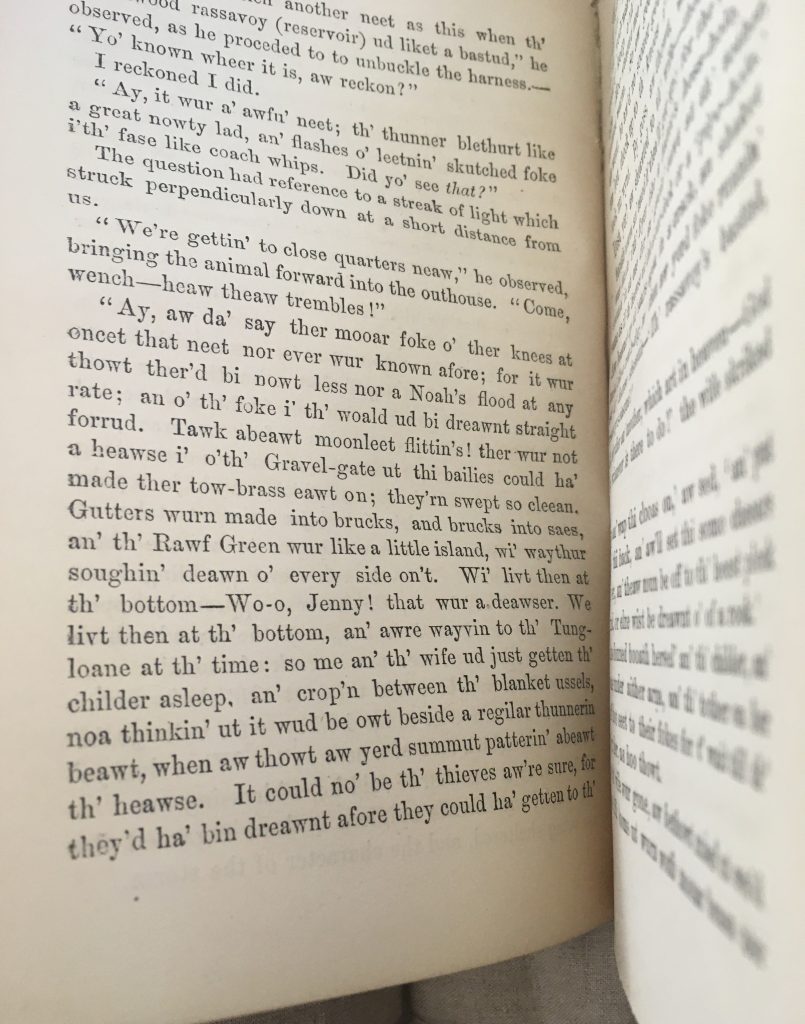

My doctoral research focuses on literary representations of regional dialects in nineteenth-century fiction. The novel writers I consider sought to set down the sounds of their regional dialects in the decades before the invention of the Phonetic Alphabet. The dialect writing that is generated is therefore an approximation of sounds, rather than the specific schema that the Phonetic Alphabet sets out. Consequently, there are often disputes—usually humorous in nature—among dialect writers during the 1860s and 1870s about the correct and authentic way to represent a regional sound.

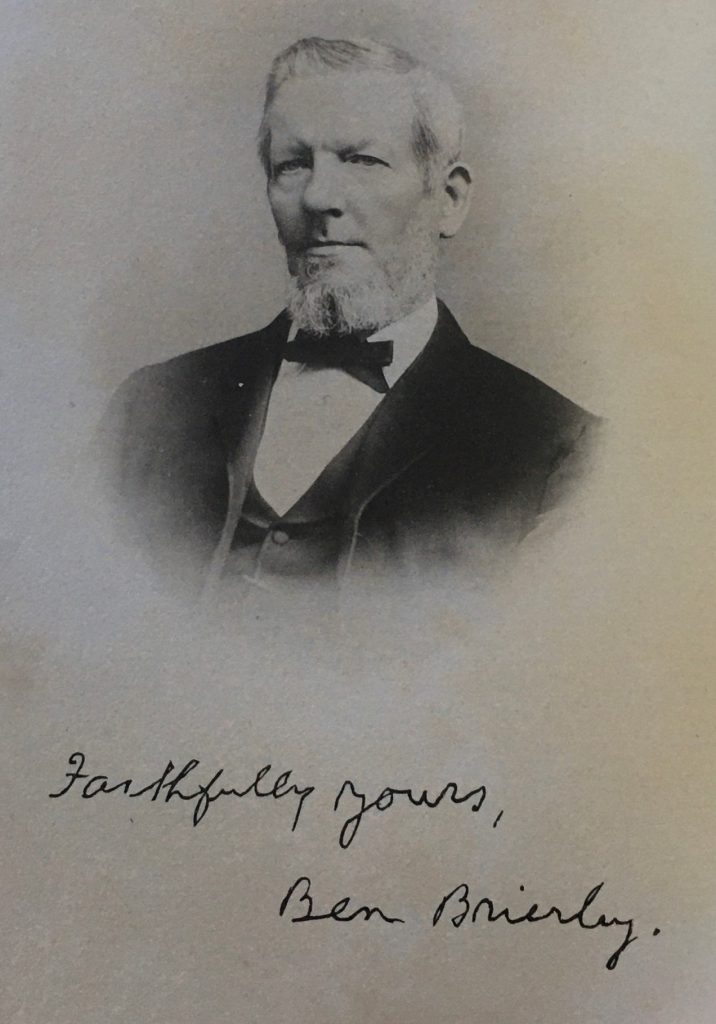

Ben Brierley was born in Failsworth, Lancashire, in 1825. He worked alongside his father as a handloom weaver from his family home, and then began to publish sketches and short stories in local newspapers while also working in a silk warehouse in Manchester in the 1840s. The autodidact’s ability to speak to and about his local region is shown through the fact that Brierley was able to support comfortably himself as a writer for several decades. Brierely is especially known for his Ab-o’th’-Yate serial, where much of the humour comes from mutual misunderstandings between the eponymous Ab and those don’t speak his broad Lancashire dialect. In Ab-o’th’-Yate in London, Ab can’t understand ‘Lunnon’ vocabulary when ordering breakfast:

“Two pints of coffee?” he said.

“Two pints.”

“How many slices?”

“It depends on th’ thickness. Bring a stack!” aw said.

“Crast or crammy?”

Aw didno’ know what he meant by that, but aw ventured upo’ “crammy”, thinking it met be better for one’s teeth.

“Rasher?”

“What’s that?”

“Bacon.”

“Nawe, no Lunnon pig for me! they feeden ’em too queerly, if o be true one reads abeaut ’em!”

Many of Brierley’s texts conclude with the sense that, no matter how large, impressive or humorous other cities might be, it is only in the Lancashire region that one finds straightforward and earnest connection with others. The Lancashire dialect speaker is often a figure of fun, but also of authenticity.

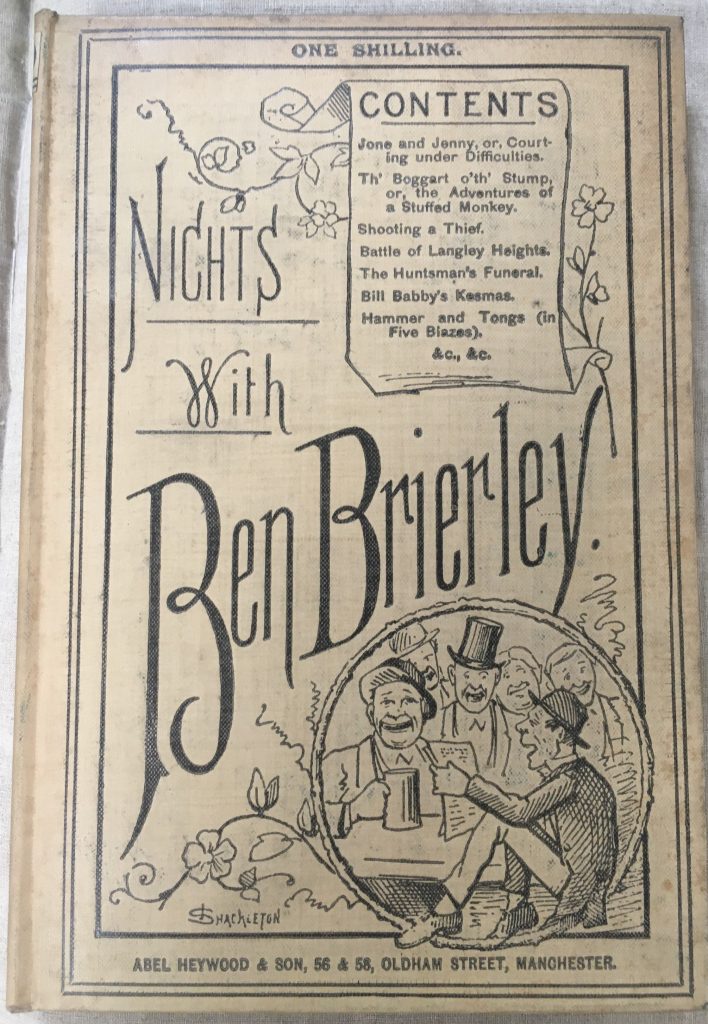

Nights with Ben Brierley (?1885), 1885.7.1040

Brierley’s “Ab-o’th’-Yate” sketches (1896), Misc.7.89.1392

But this sense of connection to one’s region does not remain solely within the novels themselves. I have recently been exploring Brierley and others’ performances of their dialect writing in public halls and local spaces. Much like Charles Dickens’s wildly popular reading events in the 1860s, local writers would tour their regions, performing from their own texts in suburban halls, Mechanics’ Institutes, and schools. Events would include musical accompaniments and ballads, and often had a charitable affiliation for local causes.

Benjamin Brierley’s performative readings prioritised humour above all else. Newspaper reviews describe audiences ‘almost convulsed with laughter’, while, on occasion, Brierley himself was unable to continue his performance for laughing. These reading events further established figures like Brierley as compelling representatives of their region, where the authentic Lancashire dialect was embodied in the voice of the individual writer. Brierley also adapted his work into collections for others to perform in a range of settings—from working men’s clubs to drawing room soirees. Hearing the dialect novel or farce sketch performed aloud formed a significant part of people’s leisure time, while also drawing upon and heightening the warm sense of local feeling among audiences.

Brierley’s Tales & sketches of Lancashire life (1886), 1860.6.217

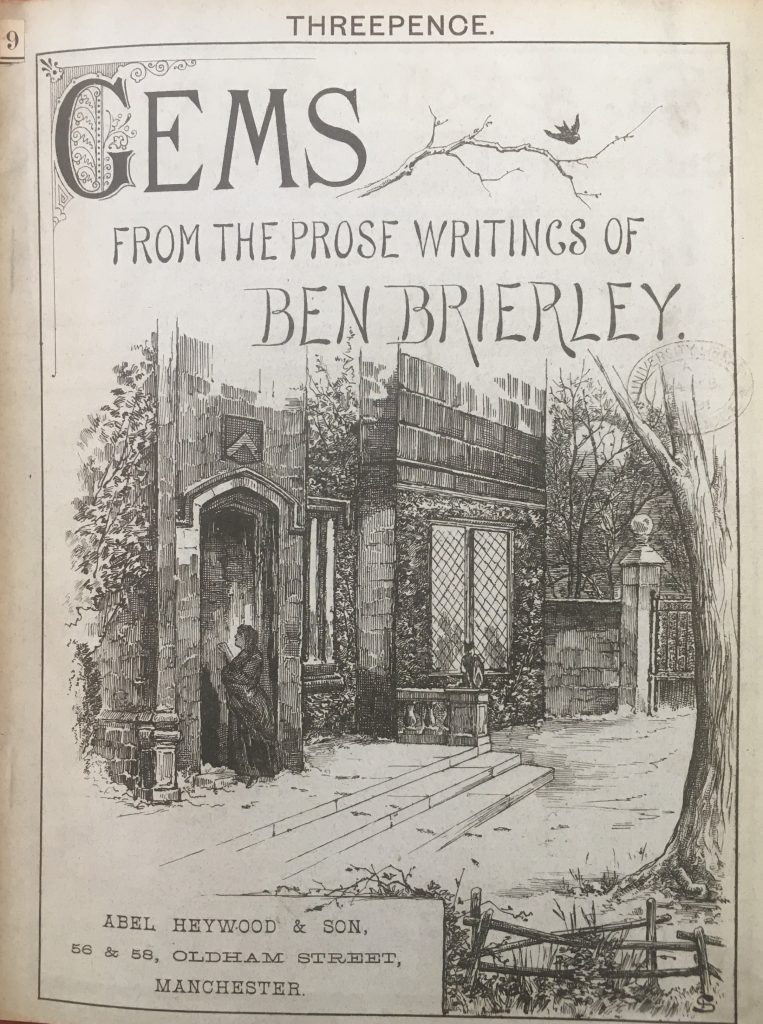

Gems from the prose work of Ben Brierley (?1891), 1891.11.9

The University Library holds a large quantity of nineteenth-century dialect material in its Rare Books collection, and academics at the University at the time included W. W. Skeat, first Elrington and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon in Cambridge, and founder of the English Dialect Society, which sought to promote and preserve regional writing.. Dialect writing in the late nineteenth century is often doubly pitched: it is a source of academic interest to those involved in the study of philology, while also the fiction that working men and women chose to either read or see performed in their leisure time. Often, within nineteenth-century dialect novels, narrators or editors will refer to the fact that the particular dialect has been preserved just in time, before it is lost entirely.

Since the temporary closure of the University Library, I have needed to order some of my own copies of these texts from specialist booksellers in order to continue my research. The majority of these works have not been reprinted since the 1880s, and I feel the real responsibility of being a caretaker of rare texts. The University Library’s collection of nineteenth-century dialect material is such an important resource for understanding how local people interacted and fashioned their regional identities. I, like many other readers and researchers, very much look forward to the day I can use its collections again.

Reading your blog brought a spontaneous opening of my heart as if Ben Brierley’s spirit breathes and speaks again – his marks on paper having distilled the power of love at the core of humanity. Authenticity shines through despite print’s shortcomings and allows us to celebrate different ways of speaking as a source of shared humour and fascination rather than an excuse for derision and exclusion. Keeping regional speech systems alive holds the space open for diversity. Dialect reflects so subtly the life of a community in a setting that is real. We need this to be able to capture a range of human experience in changing times. I didn’t know this existed and I want to say thank you for painting such a vivid picture in your blog and for being a caretaker of dialect writing.