Hard luck

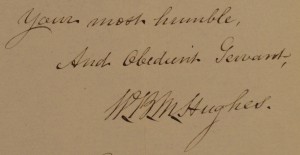

Humble and obedient, but truthful? The signature of W. B. M. Hughes from his letter to Sir John Acton. MS Add. 8119(3)/H142.

The ‘hard luck story’ has a long pedigree, and there has always been difficulty knowing how much — if anything — in each tale is true. Two letters in the correspondence of the first Lord Acton held in the University Library are a case in point.

In April 1865 Acton, at that time a baronet, who had succeeded his father and inherited the family seat of Aldenham at three years old, and whose immediate family were dead, received the following letter from a Mr W. B. M. Hughes:

‘Sir,

I could not have dared to take the liberty of writing to you, but for the unbounded kindness of your late father, Sir Richard Acton, Baronet, who presented me with £1000 on the evening he left Aldenham, for London, on his way to Italy, for having previously saved the life of Miss Acton by rescuing her from a runaway horse, in the neighbourhood of Morville, which munificent sum was dastardly taken from me by the discharged servants he left behind, by drugging the wine that was given me with some refreshment as soon as the Baronet and Lady Acton made their departure, and also that his last words on leaving me were so kindly spoken, should I fail in any undertaking I had only to let him know and he would further assist me though he might not be in England, for there would always be some one at Aldenham who could let him know.

A Fifty Pounds Bank of England Note was first given me by the Baronet, and two by Lady Acton, the other part (£850) making up the One Thousand Pounds was in gold, and given me by the numerous guests dining with them, and the Baronet was kind enough to have two small bags made to hold the gold, and securely tied them up and then put one into each pocket of my trousers and actually folded up the three notes, placed them in my right hand waistcoat pocket, and pinned them there.

Orders were also given that I should be sent down to Bridgnorth in one of the carriages of the Baronet’s retinue, for greater safety, and this far his injunctions were carried out, but on arriving at the Crown Hotel I found all my money had been taken from me, and the two females who were in the same carriage with me and who had witnessed, on the journey, that stupid and confused state that results from drugging felt assured what I had been served and more especially when they found I had been deprived of all my money persuaded me to return to the Hall and demand it — I did so — when one of the servants actually horsewhipped me off the premises. Thus was one of the noblest acts a man could have performed to benefit another frustrated by designing treachery… and though applauded for my courage and even presented to Her Majesty, at Buckingham Palace, no sooner than the Baronet so munificently remunerated me, than all my applauders appeared to envy me and gloried in my loss, and I believe that if the Bridgnorth people had actually have known, who, of those servants, took it from me they would not have told me.

I have taken this liberty, trusting you will pardon me, of explaining my sad loss to you, which for a length of time nearly destroyed my reason, to ask you if you would be so kind as to fix me in some better post than that of a Solicitors Office…. what a different position mine would have been had [Sir Richard] returned to England alive when all would have been brought to light’.

It is not known what help, if any, Acton gave Hughes, but it cannot have sufficed in the long run for thirteen years later Hughes wrote another letter, this time to Earl Granville, the second husband of Acton’s mother:

‘My Lord,

Would your Lordship be pleased to place me in one of your many Offices…. I am the person who many years ago saved the life of Miss Acton of Aldenham Hall, in Shropshire, from a runaway horse….

After this event, the late Countess Granville sent me in the month of November 1845, with her son, then about 13, now the present Lord Acton, into Germany, when I became a Cornet, and afterwards a Captain, in one of the Austro-Hungarian Hussar Regiments, through the influence of her Ladyship, and was afterwards sent with my Regiment, among others, into Upper India, on the banks of the Sutlej, to assist the English against the Sikh forces, under Runjoor Sing, and did duty there as an Aidecamp on the battlefield of Aliwal, on the 28th of January 1846, under Sir Harry Smith, when my charger was shot under me on my returning from the scene of action for the third time to the Staff.’

Not much seems to be known about the rôle played by Austro-Hungarian cavalry in forging the British Empire in India. Hughes concluded his letter: ‘everything is in so depressed a state in this town [Birmingham]… that I, my wife and two daughters, dependent on my exertions, may sink into an untimely grave before I can obtain succour through labour.’ Granville was unmoved; he sent the letter on to Acton, asking: ‘Is the writer of the enclosed a madman, or an impostor — or have I entirely lost my memory?’

The two letters have the classmarks MSS Add. 8119(3)/H142 and 8121(6)/199, and may be consulted in the Library by anyone holding a reader’s card valid for the Manuscripts Reading Room.