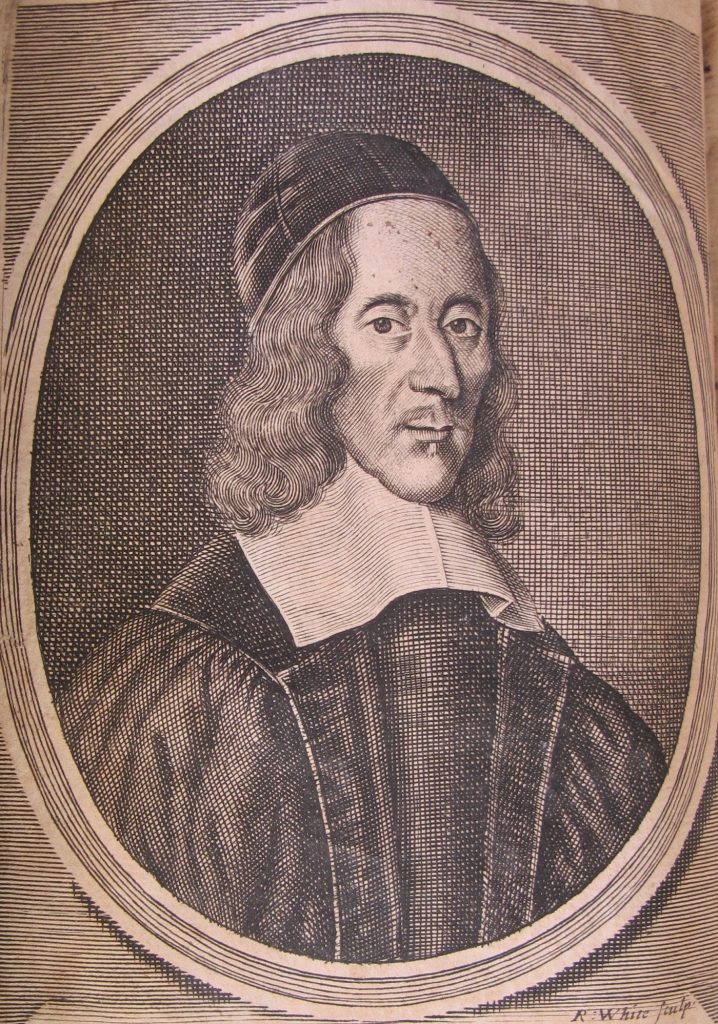

‘The finest place in the University’: George Herbert (1593-1633), Public Orator

By Jacqueline Cox (Keeper of University Archives)

2020 marks the 400th anniversary of the election of the poet George Herbert as Public Orator, a post he held until 1627. First created by university statute in about 1521, the office required the writing of eloquent addresses and official letters in Latin to the sovereign and other important individuals and institutions. It is ‘the finest place in the University’ he wrote to his stepfather Sir John Danvers ‘… for the Orator writes all the University Letters, makes all the Orations, be it to King, Prince … he takes place next the Doctors, is at all their Assemblies and Meetings, and sits above the Proctors, … and such like Gaynesses, which will please a young man well’[1]. The University continues to employ an Orator (‘Public’ disappeared from the title in 1929) though duties now focus chiefly on composing and delivering speeches, still in Latin, celebrating the achievements of those awarded honorary degrees.

Herbert’s association with Cambridge had begun 11 years earlier in 1609 on admission to Trinity College as a Westminster scholar. He graduated BA in 1613 and became a Minor Fellow the following year. On taking his MA in 1616 he progressed to Major Fellow, which status committed him to ordination within seven years. He served as Assistant Lecturer at Trinity in 1617, University Praelector (or Reader) in Rhetoric in 1618 and Deputy Orator in 1619. He had been ordained by July 1626 when he was installed as canon of Lincoln cathedral and prebend of Leighton, Huntingdonshire.

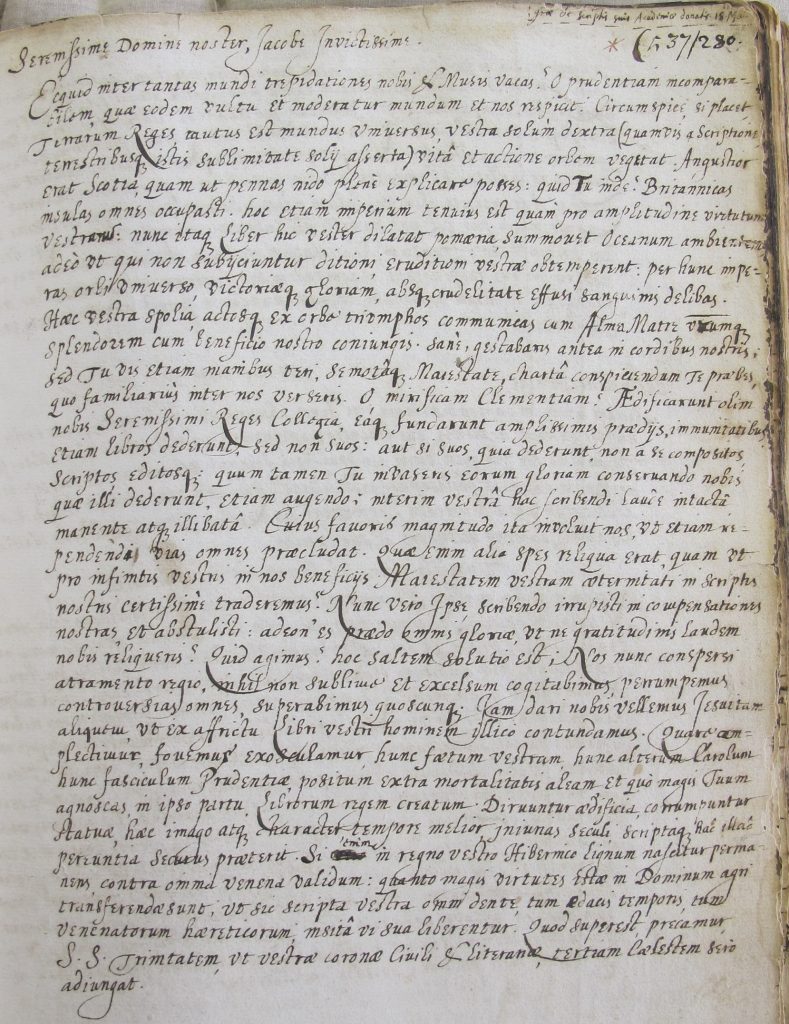

Perhaps Herbert saw the position of Orator as the means of advancing a career at Court since his two predecessors in the post both went on to become secretaries of state. Rhetorical skill had to be combined with political acumen. He wrote 18 speeches and letters in the role of which 16 survive as copies with his autograph annotations at their head in the official letter book of the University. Among the first was one thanking James I for a copy of his collected works, flattering him that other kings had given books but none before his own book. Appended was an epigram asserting that if visitors to Cambridge looked in vain for a library like the Vatican or Bodleian, Cambridge could answer that the king’s book was a library in itself. This was too insincere to take in even the vain king himself, says his biographer, but it would have amused him[2].

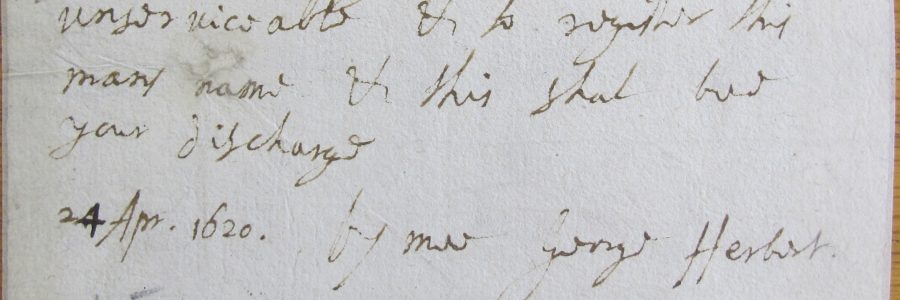

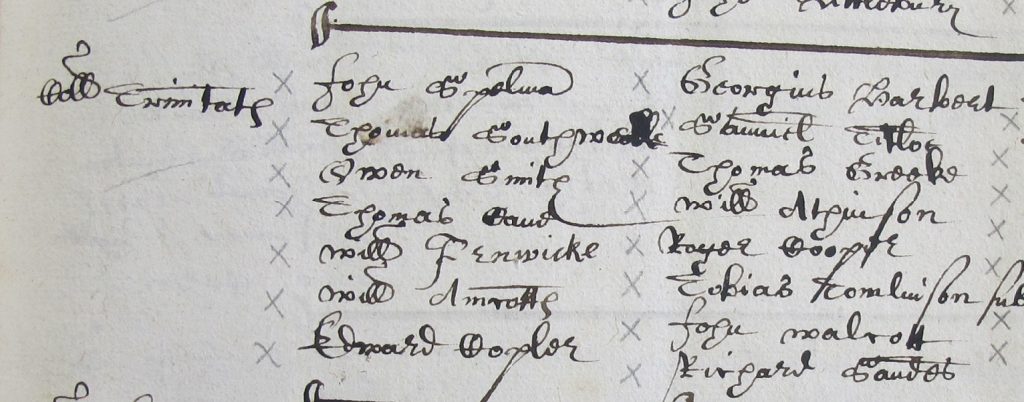

Herbert scholars have argued that he had ceased to be active as Orator in Cambridge by 1624, citing his election that year as MP for Montgomery. Its usefulness disproved, they say, his ambition was now elsewhere. However, recent work in the University Archives on the records of ‘privilege’, the perk by which servants of University officers among others could be sworn-in as quasi members of the University (with all that that implied for use of the University courts and avoidance of local taxes), may modify that view. A rare autograph request in 1620 that his man Edward Parrett be sworn (see header image, UA VCCt.III.24.115), was followed by a register entry for the same for one George Levers in 1626, perhaps indicating a more enduring connection.

In March 1629 Herbert married Janes Danvers. A year later he made a full-time commitment to the church as rector of Bemerton, Wiltshire. As he had done since he was a student however, he continued to compose; writing sonnets, satirical Latin epigrams and devotional poetry. He died of consumption, on 1 March 1633.

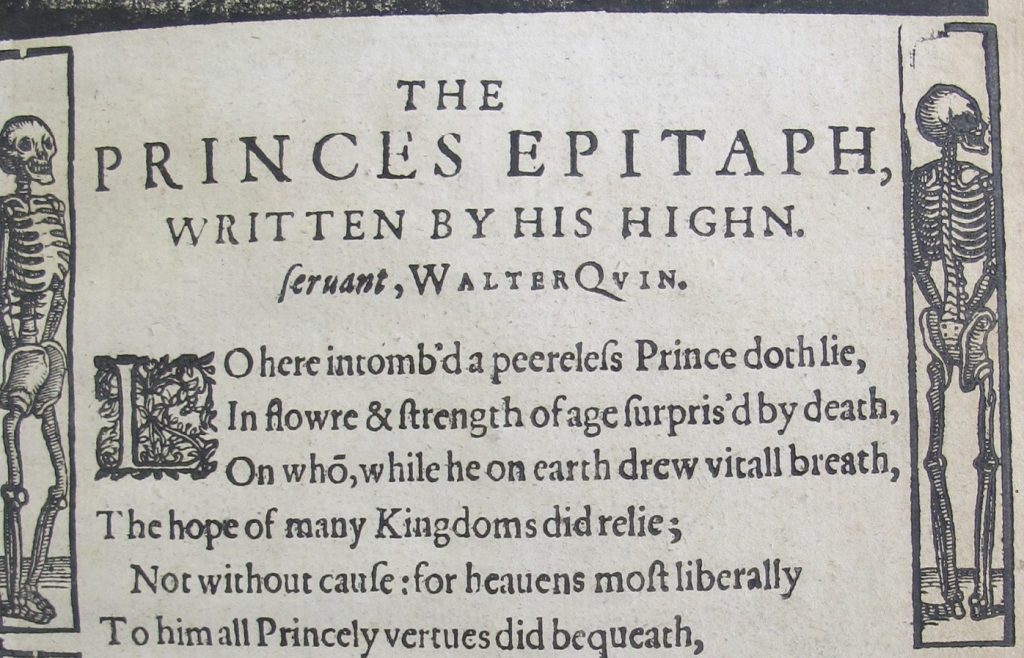

Published work by Herbert was rare in his lifetime. But of the few in Latin, his earliest appeared while still a young scholar in the form of two poems in Lacrymae Lachrimarum (1612). This was a Cambridge collection of elegies on the death of Prince Henry, heir to James I, dead of typhoid at 18. It is a small book and many of the pages are covered in black ink, bordered with skeletons.

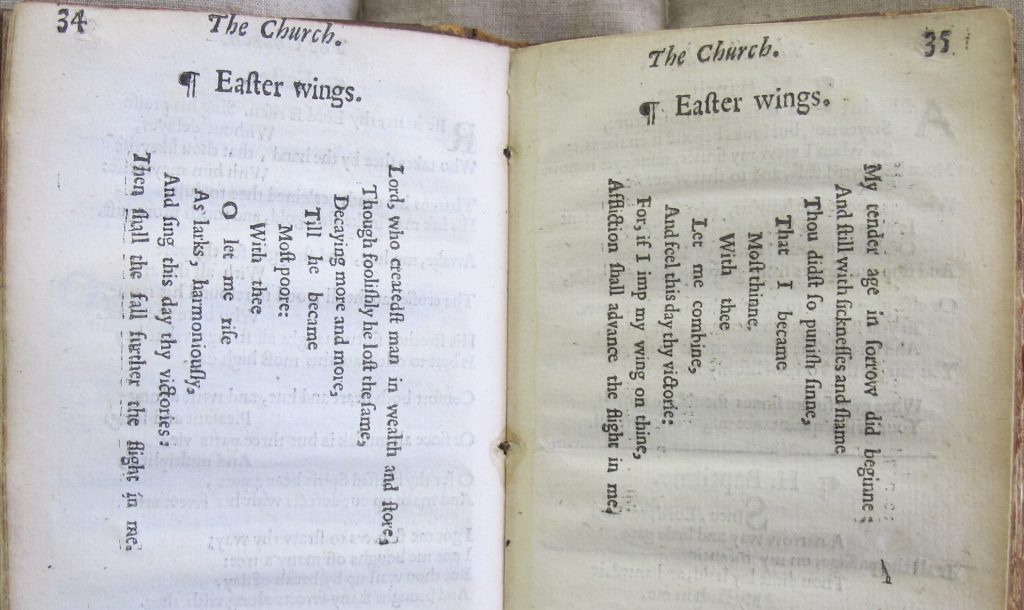

The verse for which he is most famous appeared posthumously. His friend Nicholas Ferrar made a selection from the manuscript Herbert had sent him on his deathbed and had it expertly set by the University’s printer, Thomas Buck, by September 1633. Published as The temple: sacred poems and private ejaculations (1633), the edition broke new ground in terms of production. The poem ‘Easter Wings’, for instance, had its lines printed vertically to resemble the wings of an angel or butterfly. Admirers of the ‘late Oratour’ enjoyed the inventive form and versatility with which he wrote, the poems’ simplicity of purpose and manner. The collection had been reprinted 20 times by 1680.

There is a commemorative window to George Herbert in All Saints’ Church, Jesus Lane, Cambridge.

[1] The works of George Herbert, ed. F. E. Hutchinson (1941)