Miss Lucy Nevile’s Letter of 1902: the acquisition of pre-modern Korean Christian texts in the University Library

This guest post is by Ria Roy, a PhD candidate in Cambridge’s Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies. Ria Roy is a historian of modern East Asia, focusing on the cultural and the intellectual history of North Korea. In a project supported by the Korea Foundation, she worked with University Library over the past year as a part-time assistant with the Korean collection and catalogued some of the Korean rare books before the lockdown.

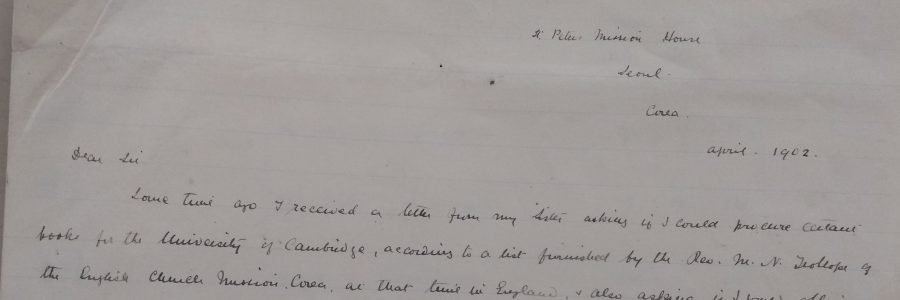

A letter from Miss C. G. Lucy Nevile in 1902 (ULIB 6/4/1/43) serves as an interesting window to understand the acquisition of premodern Korean Christian texts for the University Library. Ms. Nevile sent these books around a decade before the University Library’s acquisition in 1911 and 1913 of early Japanese books procured by Western visitors to Japan. Her letter and the accompanying lists of books provide us with an intriguing glimpse into the early Anglican mission to Korea, the “Hermit Kingdom”, next to its neighbours, China and Japan, in the late nineteenth century.

Although not much is known about Lucy Nevile herself, the letter and the records of the early Anglican Missions to Korea show that the missionaries were curious about the culture, the language and the literature of the society that they were in, as well as wanting to procure the published works by other missionaries in Korea at the time. Nevile’s letter in April 1902 was a response to an earlier letter from her “Sister” back in England requesting her to procure certain Korean books for the University of Cambridge based on a list made by the Rev. Mark Napier Trollope of the English Church Mission to Korea, works published by American, English and French missionaries at that time in Korea, and also texts in Pali and Tibetan. Nevile writes that having had no experience buying Korean books herself, she sought recommendations from Rev. J. S. Gale of the American Mission, who was also the Chairman of the “Korean Tract Society”.

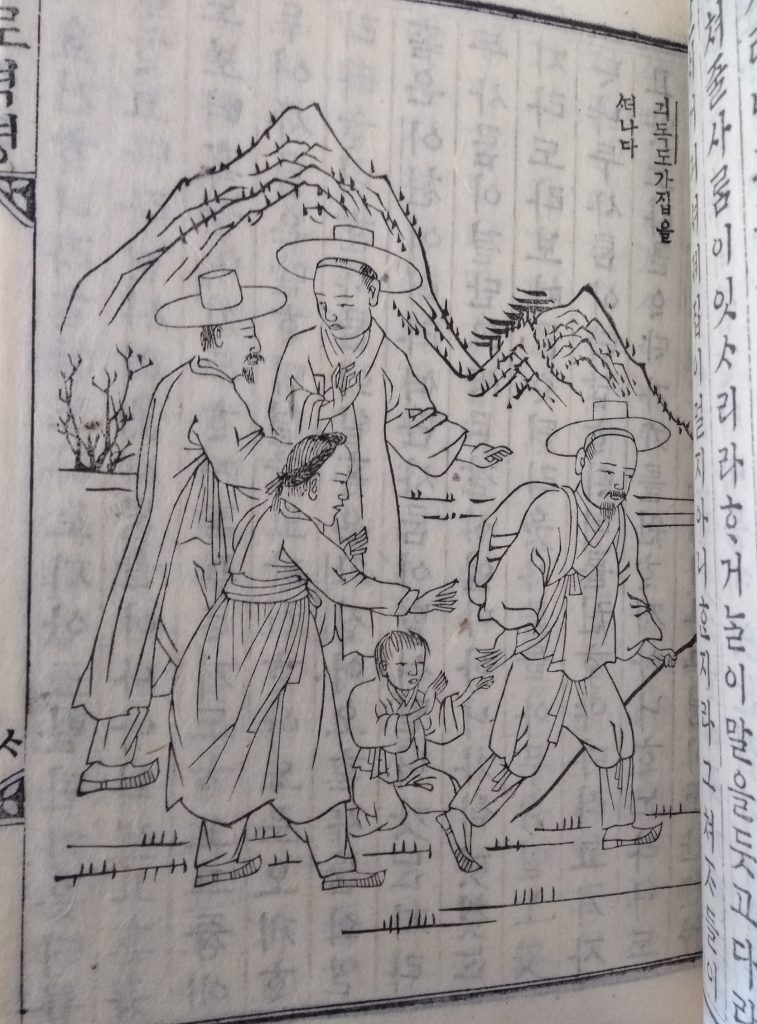

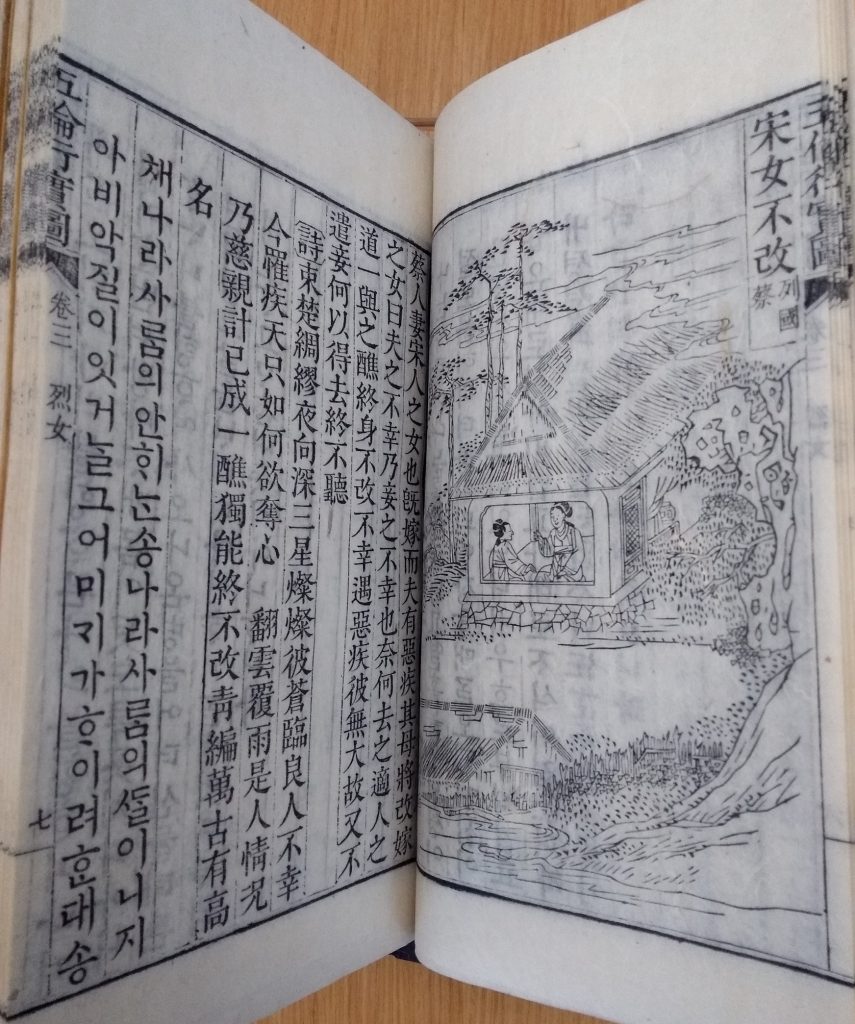

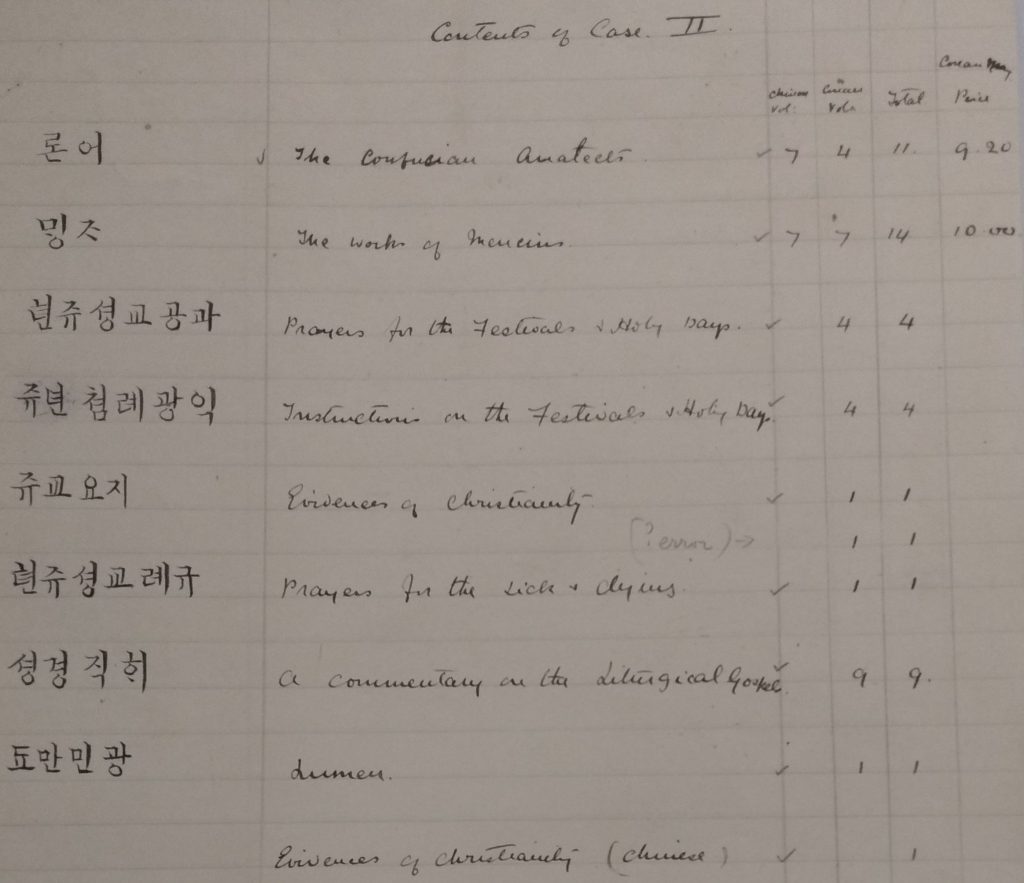

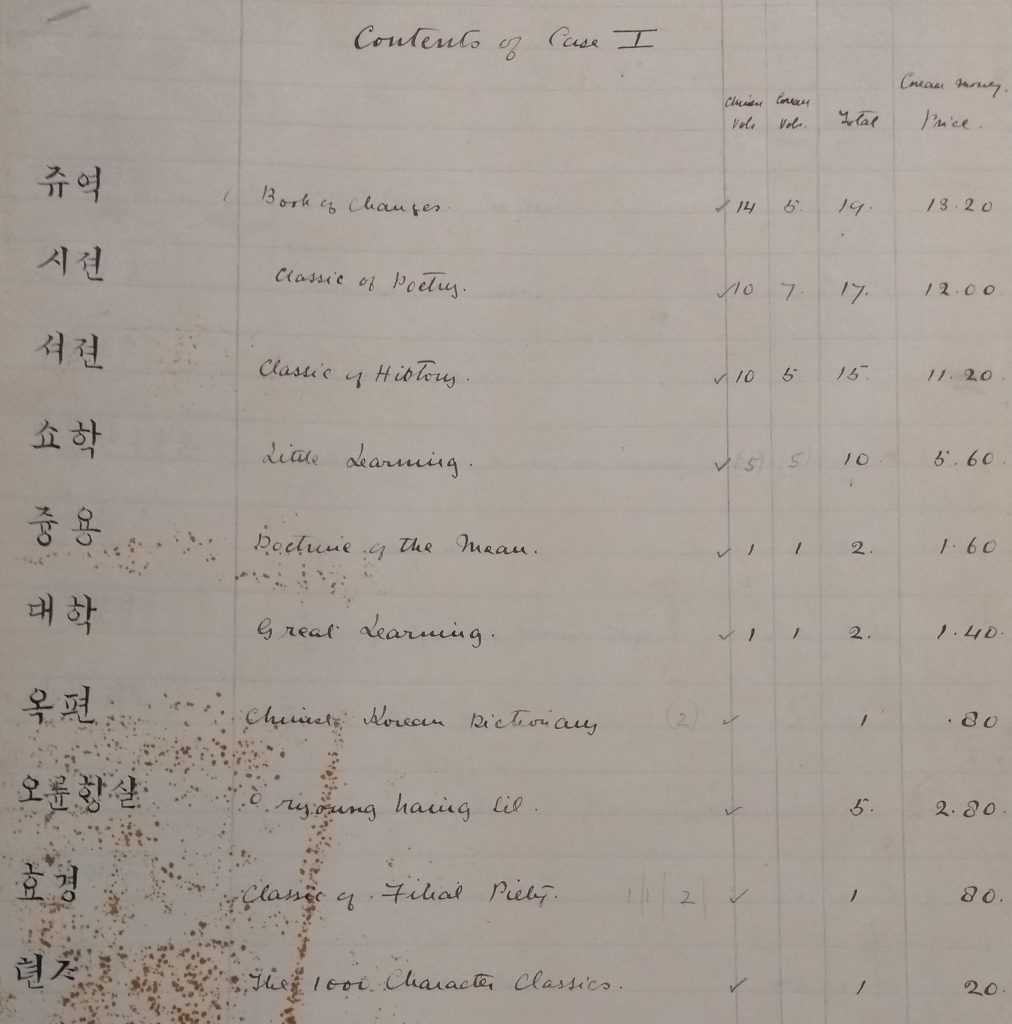

The texts in Nevile’s collection can broadly be divided into three categories: Anglican publications, other Christian publications and Korean texts—classical works well-known to the elites at the time, a dictionary and novels written in Chinese and in Korean. These included texts such as The Confucian Analects (논어, Nonŏ) , The Works of Mencius (맹자, Maengja), The Book of Changes (주역, Chuyŏk), The Classic of History (서전, Sŏjŏn)and The Great Learning (대학, Taehak), to a dictionary (옥편, Okpʻyŏn) and novels from the Chosŏn dynasty, including The Tale of Sim Chʻŏng (심청전, Sim Chʻŏng Chŏn), and The Tale of General Im (임장군전, Im Changgun Chŏn), just to name a few. This wide array of books seems to reflect an interest in the culture and the language used, something that would have been in line with the views actively encouraged by those in her inner circle, such as the first Bishop in Korea, Charles John Corfe (1843-1921, Bishop from 1890 to 1904.

In this regard, it is worth briefly noting the history of the Anglican mission to Korea. The Anglican mission to Korea began as part of the older mission by the Society for the Propagation of Gospels in Foreign Parts (SPG) in China and Japan, an organisation associated with the High Church wing of the Church. Some of the early endeavours in Korea were made by both the Japanese and the Chinese Anglican missions.[1] A. C. Shaw, a key figure in the SPG in Japan, had sent one of his Japanese catechists to Korea to study the Korean language in preparation for an eventual mission. From the Chinese side, J. R. Wolfe, an Anglican missionary in the Church Missionary Society (CMS), an organisation associated with the Low Church wing of the Church, who had visited Korea in the past, had sent two Chinese catechists to the port of Busan, a city in the southern part of the peninsula.[2]

A more substantial attempt was made with the establishment of trade and diplomatic ties after the signing of the Anglo-Korean Treaty in 1883. Bishops from China and Japan who visited Korea in 1887 wrote back to Archbishop Benson in Canterbury, urging the need to develop an initiative in the Korean peninsula without delay. As a result, Charles John Corfe, a former chaplain in the Royal Navy for two decades and someone highly esteemed for his knowledge of the Far East, was consecrated as the first bishop of Korea in Westminster Abbey, marking the founding of the Mission of the English Church to Korea on the All Saints’ Day, November 1, 1889, with an annual grant of £600.[3] Consequently, the two Chinese catechists in Busan from the Church Missionary Society were withdrawn, which explains why the Anglican Church mission to Korea took on the influence of the High Church, especially in the early years.[4] One of the key contributions of Bishop John Corfe can be found in the magazine, Morning Calm, also available in Cambridge University Library, which he wrote regularly to garner more support for the Mission to Korea among Britons back home.

The English Church Mission Press was founded by John Peake in 1891. This published religious texts, as well as texts for Korean language learning for their staff.[5] One of the most important Mission Press texts procured by Miss Nevile is the Lumen ad Revelationem Gentium (A Light to Enlighten the Gentiles), or Cho Man Min Kwang in Korean, a text that was used by Bishop Corfe and the others for teaching since the Bible was not available in Korean at the time.[6] Her collection also includes the New Testament in Korean presented by the British and Foreign Bible Society, and parts of the Old Testament, catechisms, and prayer books.

What stands out is Bishop Corfe’s substantial emphasis on acquiring the language and understanding the culture of Korea. It appears that Bishop Corfe wanted the first five to six years to be devoted to language and culture, refraining from evangelization, an approach that was slightly different in terms of duration from the ones taken by the American and Canadian missionaries in Korea at the time, who generally spent less than a year studying the language before engaging with proselytization.[7] In “The Bishop’s Letter” in Morning Calm in December 1893, Bishop Corfe notes how he and the others spent the first three years learning Korean and Chinese so that they could communicate better with the Koreans. Of course, there was the added layer of difficulty in acquiring the Korean language, as they had to acquire both the Korean vernacular script, or han’gŭl, and the Chinese characters, as many of the scholarly works for the elite were written in Chinese. The push for publications and the attentiveness to the grasp of language were part of the effort to provide more clarity to the Koreans, in case they gave a false impression by poor communication. He wrote:

For nearly three years now we have been engaged in learning Corean and Chinese,

with a view to preparing some authorised book which will commend both ourselves

and our message to all classes of Coreans. When preaching and teaching, we shall for

many years be guilty of faults in style and grammar. I have felt, therefore, that

when our missionaries begin their work they should have something in their hands—

something which they may put into the hands of others—which will not be marked

with the blemishes and inaccuracies of our halting and our often unconsciously misleading speech. If they can say, “Perhaps I have expressed myself badly, but in this book you will find what I intended to say expressed accurately in language which you will understand and

respect,” I think we shall have gained a great deal. We shall show that our verbal blunders

when speaking are due, not to any flaw in the message we bring, but to the difficulties

incidental to all beginners. Then, whenever we have given a false impression by anything

that we have said, the book will come to our aid and to the aid of our hearers and correct

that false impression, whilst not the least advantage of having such a book will be that of showing the people how we desire to respect their language and their literature. We do not

say to them, “We are in <173/4> such a hurry to teach you that any tract will do to found

our half-understood spoken words upon.” On the contrary, we say to them, “For three years

we have lived amongst you and kept silence, preferring to spend that time in efforts to

prepare, in language you will understand and respect, a book treating of the fundamental

truths of the religion which we believe and which we have come here, in order that, by

our preaching, you may believe also.”Now, I must remind you once more that we have neither Prayer-book nor Catechism,

nor—what is of more importance than either—Bible. The New Testament has indeed

been translated into Corean, but none of the missionaries who were here before us are

satisfied with it. It has been revised once, and is shortly to be revised again. I could not

therefore recommend it to my clergy, nor could I afford to wait.[8]

The books procured by Nevile in 1902, almost a decade after Bishop Corfe’s letter, reflect how some of the earlier concerns that Bishop Corfe and the others had expressed had been partially addressed, or in some cases completed, as shown with the publication of the Lumen.

Not much is known about Lucy Nevile. Even confirming the few remaining records of her is challenging during this Covid period, but she seems to have been in Korea from 1899. One of the key activities carried out by the Mission was medical care, and the first Anglican modern hospitals were founded in Chemulp’o and in Seoul. Since all the Sisters were trained nurses, it seems likely that Nevile was also a trained nurse. A few photographs of Nevile in the Women’s Hospital in Seoul in 1901, and with other members of the Community of St. Peters—Elizabeth Unwin, Evelyn Cameron, and the Nurse Helen Beckley—(included with other photos of the Community of St. Peters, circa 1903-1926) remain, and they can be found in the Korean Mission Records in Birmingham University Library. The letter, too, was posted from the St. Peters Mission House in Seoul, Korea. Although more than hundred years have passed since the letter reached Cambridge, the discovery of Lucy Nevile’s letter explains the connection between the fascinating pre-modern Korean books in the University Library and the Anglican Mission to Korea, the then “Hermit Kingdom”.

Text of the Letter[9]

St. Peters Mission House, Seoul, Corea, April. 1902

Dear Sir, Some time ago I received a letter from my “Sister” asking if I could procure certain books for the University of Cambridge, according to a list furnished by the Rev. M. N. Trollope of the English Church Mission Corea, at that time in England, and also asking if I would obtain and send copies of the books published by the American, English and French Missionaries, also any books in Pali or Tibetan.

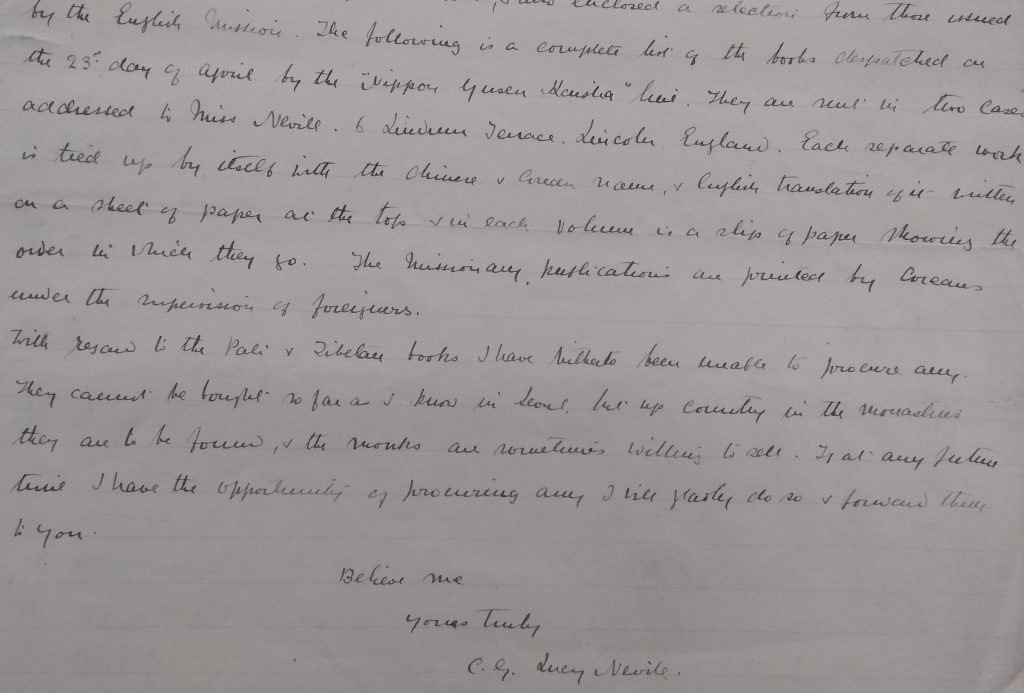

Having had no experience in buying Corean books, I wrote to the Rev. J. S. Gale of the American Mission, knowing there was no one better able to advise me, and if the result is satisfactory to you it is mainly owing to the help and advice he gave me. He also as Chairman of the “Korean Tract Society” presented on behalf of that society several works issued by them. The British and Foreign Bible Society also have presented a copy of the New Testament in Corean. On making enquiries about the French publications I was told the Rev. T. S. Badcock of the English Church Mission has a fine collection, and he selected and purchased from their depot those sent as specimens of their works, and also enclosed a selection from those issued by the English Mission. The following is a complete list of the books despatched on the 23rd day of April by the “Nippon Yusen Kaisha” line. They are sent in two cases addressed to Miss Nevill. 6 Lindum Terrace. Lincoln. England. Each separate work is tied up by itself with the Chinese and Corean name, and English translation of it written on a sheet of paper at the top and in each volume is a slip of paper showing the order in which they go. The Missionary publications are printed by Coreans under the supervision of foreigners.

With regard to the Pali and Tibetan books I have hitherto been unable to procure any. They cannot be bought so far as I know in Seoul, but up country in the monasteries they are to be found, and the monks are sometimes willing to sell. If at any future time I have the opportunity of procuring any I will gladly do so and forward them to you.

Believe me, Yours truly, C. G. Lucy Nevile.

[1] Mark Napier Trollope, The Church in Corea. 1915 available in http://anglicanhistory.org/asia/kr/trollope

1915/02.html and Sean C. Kim, “Via Media in the Land of Morning Calm: The Anglican Church in Korea,” Journal of Korean Religions Vol. 4, No. 1 (April 2013):74.

[2] Sean C. Kim, “Via Media in the Land of Morning Calm: The Anglican Church in Korea,” Journal of Korean Religions Vol. 4, No. 1 (April 2013):74.

[3] Mark Napier Trollope, The Church in Corea. 1915 available in http://anglicanhistory.org/asia/kr/trollope

1915/02.html.

[4] Sean C. Kim, “Via Media in the Land of Morning Calm: The Anglican Church in Korea,” Journal of Korean Religions Vol. 4, No. 1 (April 2013):74-75.

[5] Sean C. Kim, “Via Media in the Land of Morning Calm: The Anglican Church in Korea,” Journal of Korean Religions Vol. 4, No. 1 (April 2013):76.

[6] C.F. Pascoe quoted in Sean C. Kim, “Via Media in the Land of Morning Calm: The Anglican Church in Korea,” Journal of Korean Religions Vol. 4, No. 1 (April 2013):77.

[7] C.F. Pascoe quoted in Sean C. Kim, “Via Media in the Land of Morning Calm: The Anglican Church in Korea,” Journal of Korean Religions Vol. 4, No. 1 (April 2013):77.

[8] C. John Corfe, “The Bishop’s Letter” in August 1893, available in http://koreanchristianity.cdh.ucla.edu/images/stories/1893_Corfe_letter.pdf.

[9] ‘Corean Books Procured for the Library by Miss Nevile 1902’ in ULIB 6/4/1/43. Letter transcribed by Dr James Freeman, Ria Roy, and Dr Kristin Williams.