A Georgian Music Book

This guest post is by Francis Knights, Fellow of Fitzwilliam College, whose research interests include musical history, instruments and performance practice from the 16th to 18th centuries.

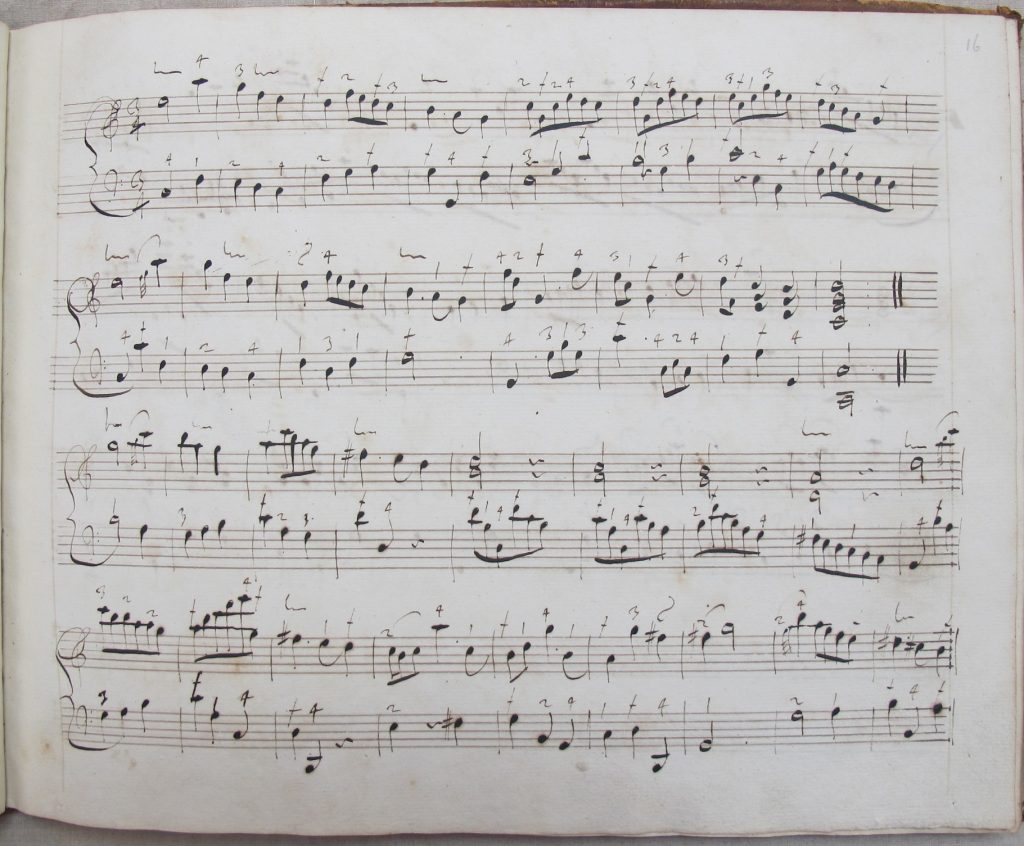

Cambridge University Library MS Add. 9127, known as ‘The Cobham Hall Spinet Book’, is one of a number of early eighteenth-century English teaching manuscripts witnessing the progress of musical amateurs in the early Georgian period. It contains a dated record of lessons received from Charles Froud in 1729-30 by an aristocratic young pupil in rural Kent. The manuscript is in a contemporary gilt-stamped leather binding, measuring 23 x 29.5 cm. The format is uniform, with 8 staves to a page across the 80 pages (illus 1); the copyist hand is clearly the work of an experienced musician, and it is reasonable to assume that this is Froud himself. It was bought from G. David Bookshop in Cambridge, probably in the late 1970s, and was first catalogued as MS 24 in the Faculty of Music’s Pendlebury Library before being transferred to the University Library.[i] Cobham Hall (illus 2), near Gravesend, is ‘one of the finest and largest great houses in Kent.’[ii] It was built on the site of a medieval manor house, and is now a girls’ school. The present building is a Tudor structure supplemented with classical additions, and was the seat of the Earls of Darnley for more than two centuries, passing out of the family in 1957 after the death of the ninth Earl. The first Earl, John Bligh (1687-1728), married Lady Theodosia Hyde (1695-1722) in Westminster Abbey in 1713; they were resident at Cobham Hall from 1725, and had five children who lived to adulthood: three daughters, Mary (c.1717-91), Theodosia (1722-77) and Ann (c.1721-89), and two sons, Edward (1715-47) and John (1719-81), successively second and third Earls.

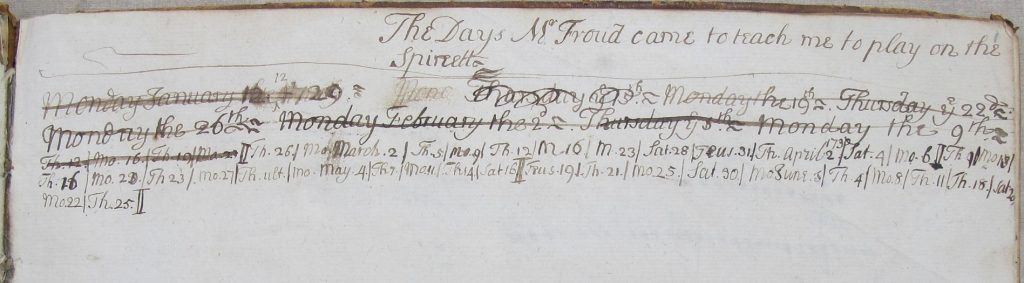

The front of the manuscript bears a note (illus 3) in handwriting suggesting a child of perhaps ten or younger, making it highly probable that the second daughter Theodosia was the pupil in question (such an education was more common for the daughters than the sons of a peer at this time). The lessons begin just after the death of the first Earl, who had survived his young wife by only six years: was this therefore an attempt either to provide music as a welcome distraction or solace for one (or all) of the three orphaned daughters, or a desire to provide them with some educational finish as they began to head towards the aristocratic marriage market? After the death of the last Earl in 1955, the contents of the house were sold at an onsite auction by Sotheby’s in 1957, and the instruments disposed of included an important harpsichord by Thomas Hancock and a chamber organ of c.1778 attributed to Samuel Green (1740-96), now in the church of St Mary the Virgin, Hastingleigh, Kent. It is likely that the Cobham Hall Spinet Book was sold at that time.

The manuscript mentions the spinet by name (f.1r), and these small triangular keyboards were made by a large number of craftsmen in Britain; they were much more common than harpsichords in Britain until about the middle of the eighteenth century.[iii] With their wide compass, light action and good tuning stability, spinets were ideal instruments for teaching, and for domestic performance and accompaniment. Of the spinet makers in London in the early eighteenth century who are represented by surviving instruments of about the right date and compass, Thomas Hancock, Thomas Hitchcock the younger and Benjamin Slade are the most likely candidates for any Cobham Hall spinet. In view of his high output of spinets and his reputation for these instruments, Hitchcock looks like the best candidate. However, there is also the interesting possibility that the word ‘spinetto’ in Add. 9127 was being used as a generic term for a stringed keyboard instrument, as Cobham Hall contained a harpsichord of exactly the right date: this important harpsichord is now in the Russell Collection at the University of Edinburgh.[iv] It is a single-manual instrument dated 1720 and made in London by Thomas Hancock (illus 4), with two registers and a compass of GG-e3 (identical with the repertoire of MS 9127); some Italianate design influence is evident. The family could of course also have owned a spinet, or indeed other keyboards, as well as the Hancock harpsichord, but the existence of this 1720 instrument is very noteworthy, and it is possible that one of the Miss Blighs did indeed have her lessons from Mr Froud on the very harpsichord that now survives at Edinburgh.

‘Mr Froud’ was Charles Froud, a professional musician who appears to have spent his career in London; the 1729 Cobham Hall date is the earliest reference to him. His date of birth is not known, but it must have been soon after 1700. In 1739 he was an original subscriber at the founding of the Royal Society of Musicians, and as well as being an organist, he was very active as a violinist in London and is recorded as having played violin (and sometimes harpsichord) in concerts there. Records show him performing from 1750-69, and he was also known to the two most important British music historians of the day, Charles Burney and John Hawkins.[v] Froud’s principal employment was as a church organist, and he held a post at the historic church of St Giles-without-Cripplegate near the Barbican in London from 25 May 1736 until his death in 1770. In 1763 Froud was listed as ‘Organist and teacher on the Harpsichord’ in Mortimer’s London Universal Dictionary, with an address at King Street, Bloomsbury. Like the first Earl of Darnley, he was a Freemason, and it is not impossible that his initial teaching role at Cobham Hall came about through Masonic contacts.

Keyboard playing appears to have become increasingly fashionable amongst the musical amateurs of the British aristocracy and middle class from the Restoration onwards. A large number of sources and instruments survive, and it is clear that finding teachers for all these new players could be more difficult for those located outside the major population centres or cultural circles. Enterprising publishers like John Playford and John Walsh filled this need with elementary tutors, comprising a few dozen simple pieces from well-known composers, prefaced by ‘instructions for learners’. The Harpsichord Master (London, 1697), for example, included four such pages of instructions attributed to Henry Purcell, explaining the basics of keyboard compass, note values, rests, time signatures, ornaments, clefs, repeats and fingering, and these appear to have been adapted for the Cobham manuscript. None of the actual pieces of music in the manuscript are attributed apart from one Handel minuet, and some detective work has been necessary to find the composers. As well as excerpts from Handel’s operas Ottone (1723), Tamerlano (1724) and Rodelinda (1725) and Poro (c.1730), there are three song arrangements from the Beggar’s Opera (1728): this is music hot off the press from London, possibly of works that members of the Bligh family had seen during their visits to London. A number of pieces that look like technical exercises offer the young player a chance to develop finger dexterity, and the half-dozen minuets are there both for melodic appeal and technical ease; many of the remaining anonymous pieces may be original compositions or arrangements by Froud himself. Several are very fully fingered, for the benefit of the pupil, and frequent ornamentation is an immediate part of the technique required. Interestingly, the reverse of the volume includes five works (two movements from a violin sonata in C major and three Italian airs) with figured bass, which suggests that Froud was wanting to start teaching his pupil accompaniment at an early stage, and that there would have been a need for such accompaniment skills at Cobham Hall. Perhaps some other of the pupil’s siblings sang or played?

The most interesting feature of the source is the index of lesson dates (illus 3), a very unusual piece of information to survive. At the front of the volume, the pupil has noted the day and date of each lesson (some of the first dates are crossed out, possibly as each lesson happened): ‘The Days Mr Froud came to teach me to play on the Spinetto’. Over a period of about six months, from January to June, forty-eight lessons took place, more than two per week. The number of pieces in Add. 9127 corresponds to about one per week, which is a plausible rate of progress. Most of the lessons were on Mondays and Thursdays, for a professional violinist and organist like Froud is likely to have kept Saturdays free for concerts and Sundays free for services. It is possible that he was local to Kent at this point, otherwise this rota would have represented long, expensive and frequent trips from London. Although the lesson record ceases in June, this does not necessarily mean that the teaching was discontinued; the pupil could have moved on to more substantial works (in manuscript or print), and left this early teaching book behind. Nothing further is known about the Bligh family’s musical education at this period, so Add. 9127 remains as the sole intriguing record of one young pupil’s first steps into music during the early eighteenth century.

[i] For a full description, see Francis Knights, ‘The Cobham Hall Spinet Book’, Early Keyboard Journal xxxi/xxxii (2014-15), pp.18-37.

[ii] Tim Tatton Brown, ‘Cobham Hall: The House and Gardens’, Archaeologia Cantiana (2002), p.1, online at kentarchaeology.org.uk.

[iii] See Peter Mole, The English Spinet with particular reference to The Schools of Keene and Hitchcock, PhD thesis (University of Edinburgh, 2009) and Donald H. Boalch, ed Charles Mould, Makers of the Harpsichord and Clavichord, 1440-1840 (Oxford, 3/1995).

[iv] Accession number 4312. There is a description of the instrument in Darryl Martin, ‘The Native Tradition in Transition: English Harpsichords circa 1680-1725’ in John Koster (ed), Aspects of Harpsichord Making in the British Isles, The Historical Harpsichord no.5 (Hillsdale, NY, 2010), pp.1-115 at pp.84-90.

[v] Simon McVeigh, Calendar of London Concerts 1750-1800 (2014), http://research.gold.ac.uk/10342/.