The Fascinating History of the ‘Buchanan Bible’ or MSS Oo. 1.1-2

Research and text by Jeremy Penner

In late Antiquity as today, the importance of the written word for the production and dissemination of knowledge cannot be understated. For words deemed holy writ, their promulgation was considered of special importance, and the extraordinary time and effort spent on the production of religious literature meant that extra care was given not only to the preservation of the text, but also to their aesthetics. The bibles produced in these centuries were not simply warehousing for divine decrees. They are also cultural objects that often carry with them a fascinating history independent of their textual contents. Tracing the lives and histories of these cultural objects can often uncover details about readership and audience, networks of influence and knowledge, sometimes with surprising results.

Consider one of the unique treasures of Cambridge University’s special collections: mss O.o. 1-2, often referred to as the ‘Buchanan Bible,’ is a Syriac language bible codex, or pandect (from the Greek: “containing everything”). It has been housed at CUL since it arrived from south India’s Malabar coast in 1808; it was likely produced in Edessa or the surrounding area late in the 12th c. Even a cursory glance reveals something about the enormous undertaking required for its production; aside from its rarity and size, the work contains dozens of detailed biblical portraits and headpieces that show an affinity with Jerusalem art culture, including some influence from the Latin world. One also finds an impressive array of languages in the marginalia that includes Greek, Armenian, and Arabic, surely indicative of a cosmopolitan context and a wide-ranging linguistic background of its readership. We know of only three other comparable works in the Syriac tradition: codex Ambrosianus housed in Ambrosian Library, Milan (ms B. 21; 6th or 7th c.); ms 341 housed in the Bibliothèque nationale, Paris (8th c.); and ms Or. 58 housed in the Laurentian Library, Florence (9th c.). A pandect of this size and quality was exceedingly rare in antiquity, particularly before the 17th c.

The uniqueness of this manuscript is also apparent in the text itself. Prior to the printing press, full pandects required a great deal of expertise and were prohibitively expensive—smaller collections of works were therefore grouped together and circulated independently of each other (e.g., the five books of Moses [Pentateuch/Torah], the Gospels, the books attributed to Solomon, David, Jeremiah, and Paul, etc.). As separate books, these groupings are quite standard and represented broadly. In this pandect we also find the Book of Women, grouping together the biblical heroines Ruth, Suzannah, Esther, and Judith. Other interesting features: The Old Testament includes 3 Maccabees and the Book of Josippon (4 Maccabees) and ends with Tobit. In the New Testament the Book of Acts is placed with the Apostolic Epistles after Paul’s letters; the pandect does not include the Book of Revelation and ends with the six books of Clement. It also excludes the story of the adulteress woman (John 7:53-8:11), a text not found in the earliest version of the Gospel. Much like the Masoretes in the Hebrew scriptural tradition, each word was counted and listed at the end of a book or group of books to ensure accurate copying. Without the colophon, just who exactly produced this impressive work and why, and how it arrived in south-west India is not well-understood and has been left to speculation. In order to more fully grasp the complexities of these questions, it is first necessary to turn to the origins of Christianity in India itself.

St. Thomas and the Origins of Christianity in India

As Christian communities continued to grow and spread throughout the Byzantine world, so, too, the traditions about Jesus and his earliest followers; by the time we reach the second century CE, apocryphal stories about the lives of the Apostles and their post-Easter dispersion activities had developed, often times into full narratives with considerable detail. Taking Jesus’ commandment to go into the world and “preach the gospel” (cf. Mark 16:15) as the starting point, these traditions tells us that Jesus’ disciples indeed took the Gospel message throughout the Roman empire and beyond.

The tradition of the Apostle Peter’s travels west from Jerusalem is probably the most well-known in the Latin world that came to dominate Europe: he ultimately ended up in Rome as first pope of the Catholic church; other apostolic examples include Andrew, who went to Greece; James the Elder to Spain; Matthew to Ethiopia. But as quickly as Christianity spread westward into Europe, it, too, expanded eastward, perhaps even outpacing its westward march. (Syriac stelae have been found as far East as China, attesting to the expansive networks and influence of the Syriac church through the Middle and Far East.) In the opposite eastly direction, a prominent tradition developed in the Persian Church of the East that is frequently cited and celebrated: The discipline Thomas went to India, establishing Christian communities in Syria and Persia along the way to the southern trading communities of the Malabar coast in India (his route to India varies in the tradition). The importance of Thomas in the tradition is still amply evident today, as Christians from this region often refer to themselves as St. Thomas Christians.

In the past scholars have often evaluated the historicity of Thomas’ far-ranging travels, but the evidence simply is not there to determine veracity; what is clear is that the tradition began to take hold in written documents in the third century CE. Both Origen (reported in Eusebius’ Historia Eccleasiastica III.1) and the Didascalia report that Thomas went East (along with Bartholomew); the most well-known work to develop this tradition is the Syriac Apocryphal Acts of Thomas (later translated into Greek); the work consists of a series of thirteen acts performed by Thomas while in India and tells us that Thomas’ final act was martyrdom. His tomb is located in Chennai, although many of his bones have been transferred to other places as relics, including Edessa.

The importance of Thomas within the Syriac tradition and Christianity in India provided a durable linchpin between St. Thomas Christians and Persian Church, with Edessa emerging as a theological and scribal hub that continued to develop the traditions of Thomas. The poet Ephrem the Syrian (306-373 CE), for example, wrote hymns about Thomas. The following except is from Ephrem’s Hymn 42, written from the perspective of the Christian devil:

…Into what land shall I fly from the just?

I stirred up Death the Apostles to slay, that by their death I might escape their blows.

But harder still am I now stricken: the Apostle I slew in India has overtaken me in Edessa; here and there he is all himself.

There went I, and there was he: here and there to my grief I find him.

By the 4th and 5th centuries, historical sources make clear many Christian communities had formed in south India with strong ties to Persia, both religiously and commercially, and for centuries were under Persian ecclesial rule.

It was not until the arrival of the Portuguese in Goa in south India in the late 15th c CE under Vasco da Gama—the first Europeans to do so by sea—, that the St. Thomas Christians had direct contact with the Latin Church. Disputations about theological differences were apparently not yet on the hearts and minds of the Portuguese when they first colonized Goa, but this began to change rapidly in the middle of the 16th c. The rise of the Mughal empire had weakened the Persian connection to the St. Thomas Christians, and the Portuguese saw this as an opportunity to assert their own form of control. They no longer allowed Persian bishops to pass through Goa to Kerala, and they established with the blessing of the Holy See an inquisitional court and held a synod at Diamper, explicitly condemning a great number of Syriac language books as heretical. The opening paragraph of the 14th decree of the first session states:

The purity of the faith being preserved by nothing more than by books of sound and holy doctrine; and on the contrary, there being nothing whereby the minds of people are more corrupted, than by books of suspicious and heretical doctrines; errors being by their means easily insinuated into the hearts of the ignorant, that read or hear them: wherefore the Synod knowing that this bishopric is full of books writ in the Syrian tongue by Nestorian heretics, and persons of other devilish sects, which abound with heresies, blasphemies and false doctrines, doth command in virtue of obedience, and upon pain of excommunication to be ipso facto incurred, that no person, of what quality and condition soever, shall from henceforward presume to keep, translate, read or hear read to others, any of the following books.[1]

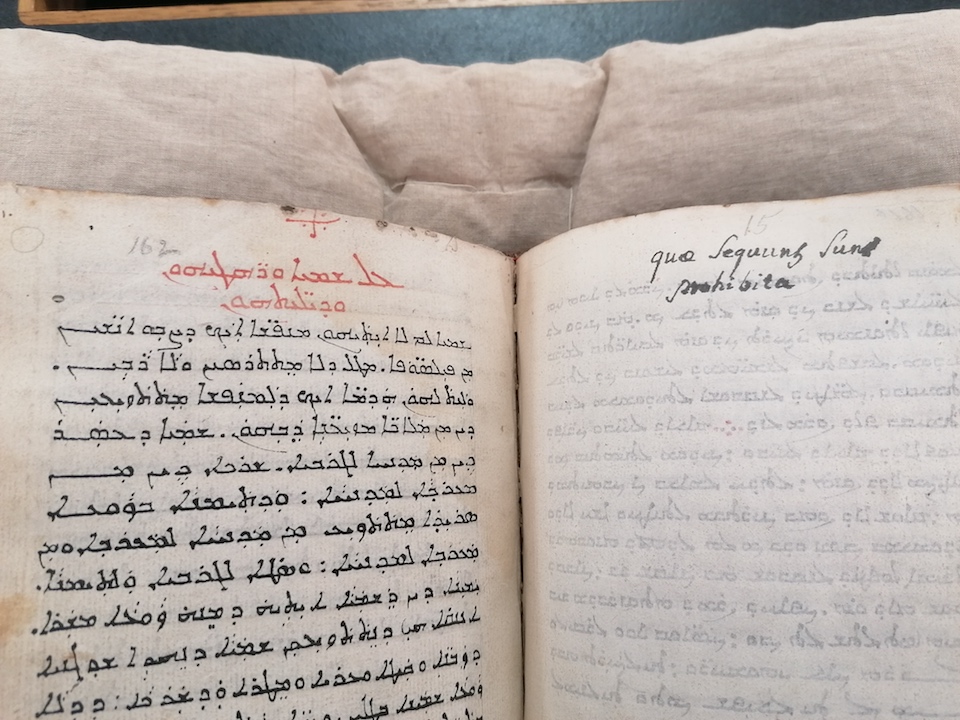

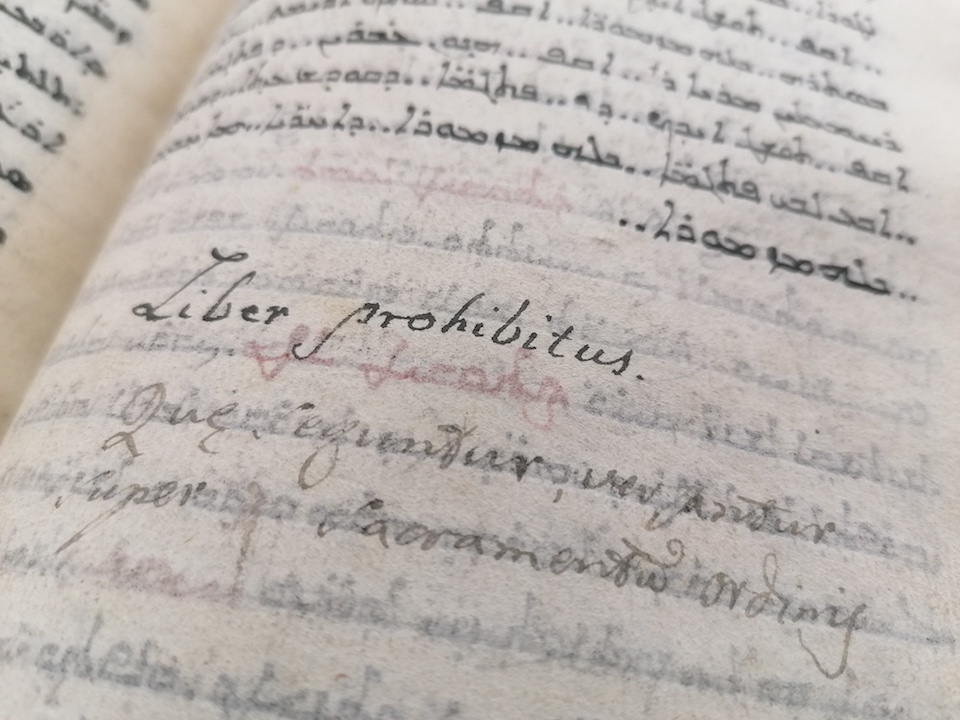

O.o 1. 29: “The following is prohibited”… Evidence of the Catholic Church’s efforts to sensor Syriac books in India

O.o 1. 29: “Prohibited book”… Evidence of the Catholic Church’s efforts to sensor Syriac books in India. This mss was brought to Cambridge by Claudius Buchanan along with the Buchanan bible and other mss.

The attempts of the Catholic Church to end the Syriac rite and replace it with Latin, often through violent means, caused a splintering of the St. Thomas Christians into a number of different denominations and communities. Some submitted to Rome, while others resisted, hiding Syriac books and continued to practice the eastern Syriac liturgy. In January 1653, a large group of St. Thomas Christians from Kochi publicly disavowed Catholic rulership in an event dubbed The Coonan Cross Oath (Koonan Kurishu Satyam in Malayalam). Mar Thoma I was elected, the first indigenous metropolitan bishop of the Thomas Christians. With European colonial interests in the Indian ocean ever increasing, Mar Thoma recognized the precariousness of his Christian community and sought the patronage, wealth, and, once again the Syriac rite of the Eastern Church. Prior to the Portugese, Thomas Christians were under the leadership of Persian bishopric; but now, direct ties were established with the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch, and in 1665, Mor Gregoios, the Syriac Orthodox Metropolitan of Jerusalem travelled to India for the ordination of Mar Thoma I.

Saint Thomas Christians maintain that it was during the active years of the Inquisition that they hid mss O.o 1-2 in the mountains of Malabar. Others have suggested that this bible was brought to India by Mor Gregorios as part of establishing ties with both communities. The reason for this argument is that the pandect was produced in the Syriac Orthodox tradition (and the West Syriac rite), which, prior to 1665, is not very well attested in south India. What is certain, however, is that the Malankara Church in possession of this bible understood its value and was very concerned for its survival in the face of a brutal Inquisition, which leads us to its deposition at Cambridge University Library.

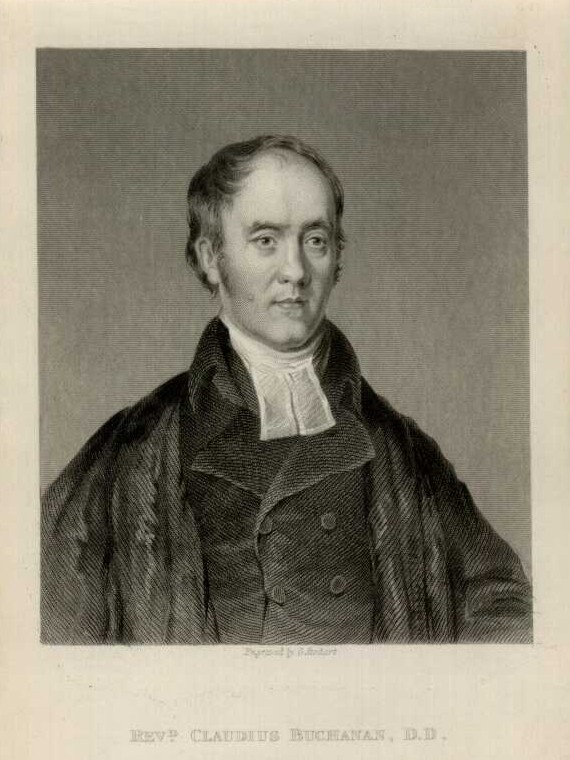

Claudius Buchanan

In 1806 a friendship was struck between Mar Thoma VI, head of the Malankara Church in Angamaly, and a chaplain from the East India Company, Claudius Buchanan. As a protestant, Buchanan had a passion for bible translation into vernacular languages, so when the Metropolitan showed Buchanan the precious manuscript a year later, Buchanan suggested that it should be used as a base text to translate the bible for the first time in Malayalam. Mar Thoma VI had apparently long hoped for such a project, and, given the recent unrest caused by Moghul leadership, gifted the bible to Buchanan to be protected and translated. (One must also remember that the Portuguese Inquisition was officially still active until 1820.) Buchanan returned to Cambridge in 1808 and later bequeathed this bible along with his library that included another 25 or so Syriac manuscripts to Cambridge University Library. By 1823 the Old Testament had been fully translated in Malayalam and copies were sent en mass to S. India, with the full project complete a few years later.

[1] Translated by Michael Geddess and edited by Scaria Zacharia in The Acts and Decrees of the Synod of Diamper 1599 (Hosanna Mount, Edamattan: Indian Institute of Christian Studies, 1994), 18.

It is time to return this Bible with all honours. It is not sold or gifted as it is given for the purpose of translation only. Translation was done in India, however the manuscript was transported to UK and kept in Cambridge. This is not property of UK and must be returned.

We Syrian Christian’s will expect a honest action from Cambridge university like how we treat others possessions in india.

https://agenda.ge/en/news/2021/1928