An epic from a tiger’s library

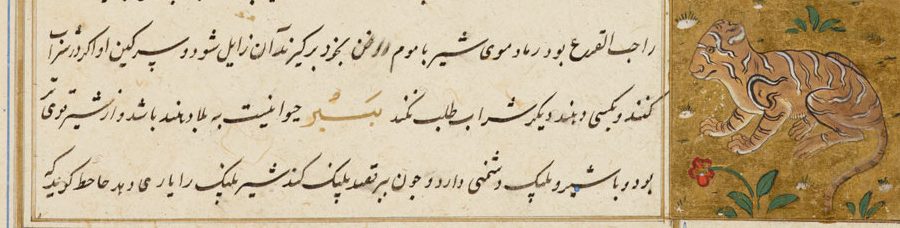

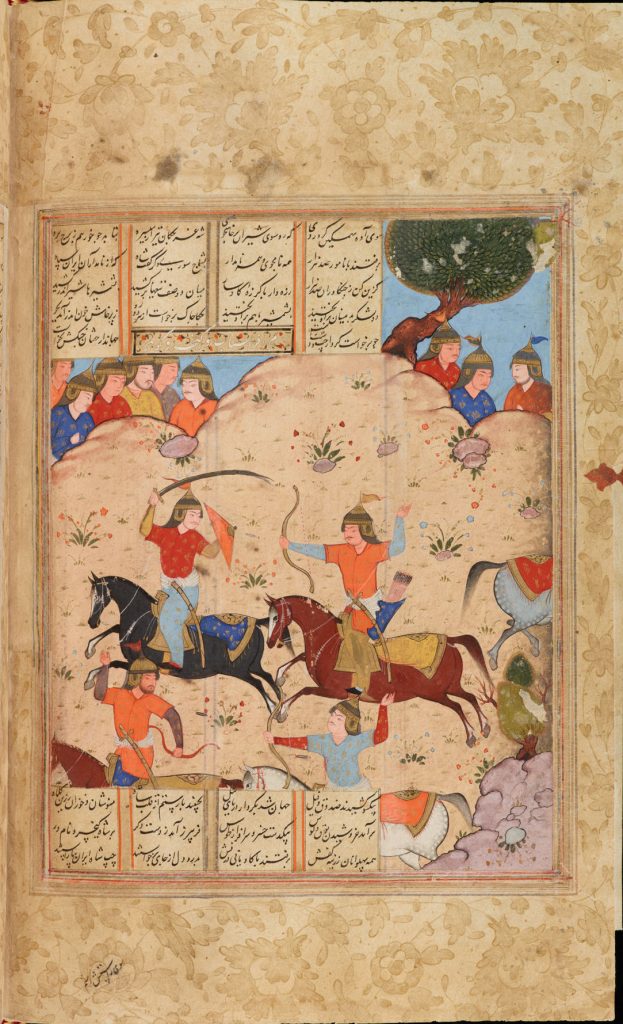

Among the many beautiful and fascinating manuscripts in the Library’s Islamic collection is one particularly magnificent copy of the famous Persian epic poem, the Shāhnāma or ‘Book of Kings’. The volume is large and heavy and contains over 550 folios of fine burnished paper sheathed in a sturdy red leather binding which is decorated with roundels in gold. Like many of the Islamic volumes, the binding has a triangular leather flap folding over the foredges of the leaves. Each of the two initial double page openings of the manuscript is richly decorated with paintings and geometrical designs and the inner leaves of the volume contain eleven full-page paintings depicting scenes from the stories within [Figs. 1, & 5]. The manuscript contains no precise indication of where or when it was made, but evidence from the decorative style commonly found in manuscripts from Shiraz or Qazwin suggest this was probably copied in Iran around 1580 C.E. Quite early in its life the manuscript travelled to India where the binding was added, possibly in the Deccan region of India. The manuscript is numbered MS Add. 269, and can be viewed in the Cambridge Digital Library

The author of the text, the poet Abu’l Qasim Firdausi was born near Tus in north-eastern Iran around 940 C.E. and devoted many years his life to the composition of his epic poem which he completed in 1010 C.E. His poetry has not only endured through time but helped to define the culture and identity of his native land. It is said that the completed poem was not well received by his patron who refused to pay him the agreed reward for his labour. Firdausi died in poverty aged around 80 and is buried in his native Tus where his tomb is revered to this day. Now, a thousand years since the poet’s death, an opportunity presents itself to celebrate the poet’s life and work.

The Shāhnāma is a poem conceived on an heroic scale, originally composed to be recited aloud. It opens with an account of the creation of the universe, continues with the story of Iran’s pre-Islamic past, encompassing both legendary and historical ages, beginning with Alexander the Great. It describes the lives of kings and heroes over the centuries, ending with the last king of the Sassanid dynasty at the time of the Arab conquest of Iran in the mid-7th century C.E. Firdausi interweaves into this narrative a host of stories and legends, such as the exploits of the great folk hero Rustam, as well as other heroes like Suhrab, Tus, and Bizhan. The background theme is the history of the Iranian people, but the underlying themes are those of the continual conflict between good and evil, the nature of kingship, of social justice and the importance of the loyalty of the common man to his ruler.

The text of the poem has been copied many times and manuscript versions of the text became widespread throughout Iran and neighbouring regions, including the courts of the Mughal states in India, in Central Asia and the Mongol Empire. Demand also came for the Ottoman Turks who appropriated the heroic message of the Shāhnāma which became known within the Turkish court where a local variant of the text was produced. The text is also the most widely illustrated narrative in Iranian culture and the paintings and decorative details found in many of the manuscripts from the 14thcentury onwards add to its popularity with both patrons and collectors.

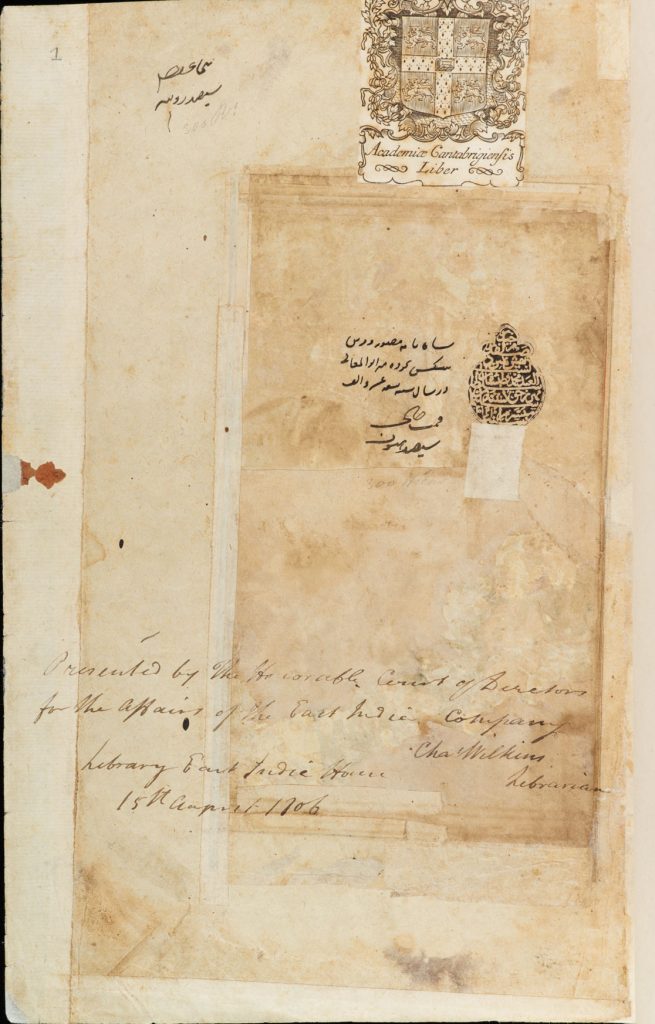

Within the volume there is evidence indicating how the Library’s finest Shāhnāma manuscript came to Cambridge after spending the first two hundred years of its life in Persia and South India. On the opening folio is the drop-shaped seal, dated 1012 A.H. (1603/4 C.E.), of Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah, the Sultan of Golconda who reigned from 1580 to 1611 C.E. Known as a scholar and a poet, writing in both Persian and Urdu, he had his own personal library collection. At the foot of the very same page there is also a note stating that the volume was presented to Cambridge by the ‘Honourable Court of Directors for the Affairs of the East India Company’, signed by Charles Wilkins, its librarian, on 15th August 1806 [Fig. 2]. It is Wilkins who provides a vital link in the story of the Shahnama manuscript’s journey from India to Cambridge. But the roles played by Sultan Quli Qutb Shah and Wilkins are only part of a much longer narrative.

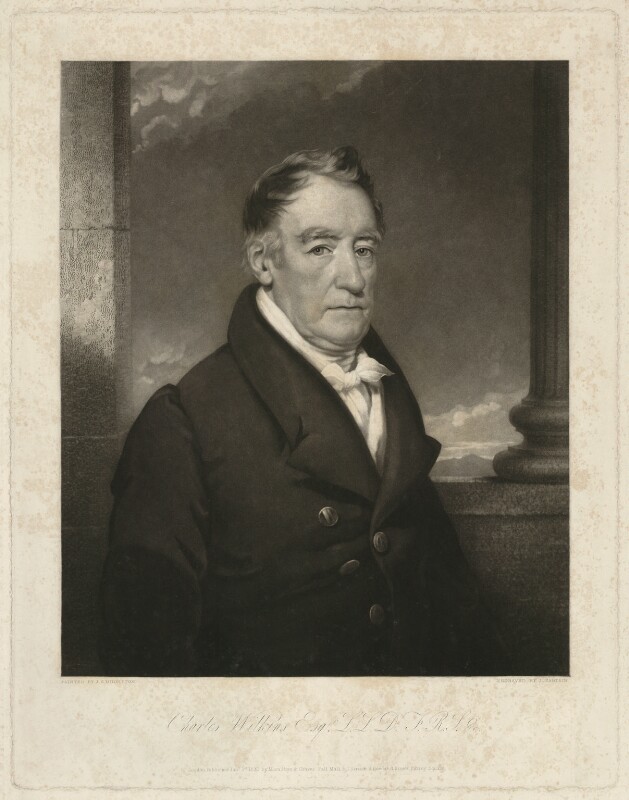

Charles Wilkins (1749 – 1836), was an important figure in the history of Indian language scholarship and was said to have been the first Englishman to master Sanskrit [Fig. 3]. Born in Somerset and trained as a printer, he later secured a writership with the East India Company in Bengal where he studied Persian and Bengali. After becoming superintendent of the company’s factories in Malda, he was appointed translator of Bengali and Persian in the Revenue Department. His printing skills enabled him to play a significant role in the foundation one of the very first printing presses for Bengali script, and which in 1788 established a new era of printing in India. Wilkins became known as the ‘Caxton of India’. With the encouragement of Warren Hastings, the Governor-General of India, he produced the first translation of parts of the Indian epic the Mahabharata, including, in 1785, the Bhagavad Gita. Wilkins also became a great friend of Sir William Jones, the Sanskrit scholar and with others who together founded the Asiatic Society in Calcutta in 1784. Calcutta became a new centre for Indian language studies, a movement which later spread to European scholars.

Wilkins remained in India until 1786 when, for health reasons, he returned to London. He continued to publish further translations from Sanskrit including the texts of the Hitopadesa and Sakuntala. He also wrote a Sanskrit grammar in the preface of which he describes the successes and woes of his printing exploits. In 1800, based on his expert knowledge of Indian languages and literature, Wilkins was appointed the first Director of the recently established East India Company Library in India House, London.

As the ex libris note on the opening folio of the Cambridge Shahnama states, Charles Wilkins sent the manuscript to Cambridge in 1806 as a gift, it was one of twelve manuscripts send as gifts from the Company to the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge and to the King around this date. A Qur’an, with very similar annotations and dated 1807, can be found in a volume in the Royal Collections. This volume also contains a note, just above a similar dedication by Wilkins, recording it as a gift to King George III ‘from the Library of the late Tippoo Sultan’. It is this larger-than-life figure of Tipu who could be said, at least in spirit, to fill the gap on the opening leaf of the Shahnama between the Golconda seal and the note by Wilkins.

Tipu, the Sultan of the state of Mysore in southern India from 1782 to 1799 C.E. had amassed a large library [Fig. 4]. He was an avid collector of manuscripts which he read for his own interests and carefully curated. It is not known in detail how Tupu had acquired his library but possibly it was accumulated partly through plunder or possibly as diplomatic gifts. His library was said to comprise at least 2,000 volumes, very possibly many more, and some volumes had belonged previously to other local rulers such as the Qutb Shahs of Golconda. No complete inventory of Tipu’s library is known to exist, though the East India Company officer Charles Stewart produced a catalogue listing 1000 works and which contains an entry for a Shahnama manuscript consistent with Cambridge’s copy. He also mentions the transfer of manuscripts to Cambridge.

Tipu was a colourful figure also known as the ‘Tiger of Mysore’ and used the tiger motif very widely as his personal identifier in public life. His spectacular automated wooden tiger figure is now displayed in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and he included the tiger image in the personal seals found in some of his own books. Tipu was also an ardent opponent of the British presence in India and in the final decades of the 18thcentury, challenged the forces of the East India Company in the Anglo-Mysore wars. During the Fourth Mysore War fought in 1799 C.E., his army was defeated and Tipu himself was killed in battle in his capital city of Seringapatam. After the conflict, his treasury was looted, and his library appropriated by the British. Some of the volumes disappeared without trace, but the core of the library remained in the hands of the East India Company who were fully aware of its value. However, rival factions within the British forces differed in their plans for its future.

The Governor-General of India, Richard Wellesley, looked upon Tipu’s library as relevant to his own expansionist political ambitions for the British in India and intended to transfer it to the College of Fort William in Calcutta which he had recently founded. In contrast, the directors of the East India Company, who did not share such political ambitions, wanted to retain the volumes to form a library and museum collection in London, an idea first suggested by Wilkins in 1798, long before Tipu’s library came into their hands. The conflict dragged on until 1805 by which time Wellesley had been replaced as Governor-General and the wishes of the Company prevailed. Only some of the books were retained in Calcutta (which came to London later in 1837) and the greater part of the collection, around 600 volumes in all, was sent to East India House in London between 1806 and 1808. Among these were the volumes which were distributed as gifts to the King and to the Universities, and three of which, including the Shāhnāma, came to Cambridge. The greater part of Tipu’s library, which came to East India House, later formed a core part of the East India Company’s library. This was later transferred, in 1858, to the India Office Library in Whitehall and more recently, 1982, incorporated into the British Library’s Asian and African Collections where it has been recently researched by Ursula Sims Williams.

Fig. 5. Decorative border from the opening page of text. MS Add. 269, fol. 2v

In recent years, Cambridge has also become a centre for study of the Shāhnāma text, of aspects of its later reception and of the manuscript copies and their art. In 1999, Charles Melville established the Cambridge Shahnama Project, originally funded by the British Academy. In 2014, The Cambridge Shahnama Centre for Persian Studies was established thanks to a generous endowment by Bita Daryabari, and Firuza Abdullaeva became the first head of the Centre. Both have studied the text in depth and written widely on its many aspects. The Centre mounted celebrations both of the millennium of the completion of the Shāhnāma text in 2010 and of the death of Firdausi in 2020. Also, at the core of the Shahnama Project, created by the director and his international team is an online corpus of the paintings which aims to include all the illustrations found in Shahnama manuscripts in collections world-wide.

Also in recent years, the Library’s fine copy of the epic, Add. 269, which had suffered some damage and deterioration in its condition over its 400-year history became the subject of a major conservation project by Kristine Rose and Deborah Farndell from the Library’s Conservation Department team. Their work included the repair of pages which had become torn or had suffered damage by the deterioration of copper-based pigments used in the decoration. The original binding and flap were detached from the text and carefully repaired and re-attached to the text. A permanent storage box constructed to house the manuscript and it can now be used once again by researchers in the Library’s reading room.

Such careful work reflects how such a treasure, although now far from its original home, continues to be valued and secure. Perhaps Tipu Sultan himself would have appreciated that.

References

Abdullaeva, F. The Shahnameh in Persian literary history. In Epic of the Persian Kings: the art of Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, ed. Brend, B. and Melville C. London, 2010, p. 16-22

Abdullaeva, F. and Melville, C. The Persian Book of Kings: Ibrahim Sultan’s Shahnama. Oxford, 2008.

Arberry, A.J. The library of the India Office: a historical sketch. London, 1938.

Ehrlich, J. Plunder and Prestige: Tipu Sultan’s Library and the Making of British India.South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 2020, v. 43:3, 478-492

Iranian Studies 43:1, 2010, Millennium of the Shahnama of Firdausi [Special Issue], Abdullaeva, F. and Melville, C. eds

Melville, C. and Van den Berg, G. eds. Shahnama Studies II-III: the reception of Firdausi’s Shahnama. Brill, 2012-18.

Rose, K.The Conservation of a seventeenth-century Persian Shahnama. In Edinburgh Conference papers 2006, ed. Shulla Jaques. London: Institute of Conservation, 2007. p. 79-86.

Stewart, C. A descriptive catalogue of the oriental library of the late Tippoo Sultan of Mysore. Cambridge, 1809.

Wilkins, C. Grammar of the Sanskrit language. London, 1808.

~~~

The featured image is a tiger from ʻAjāʼib al-makhlūqāt. MS Nn.3.74, fol. 214v