From Spare Room to Reading Room: the journey of an archive collection

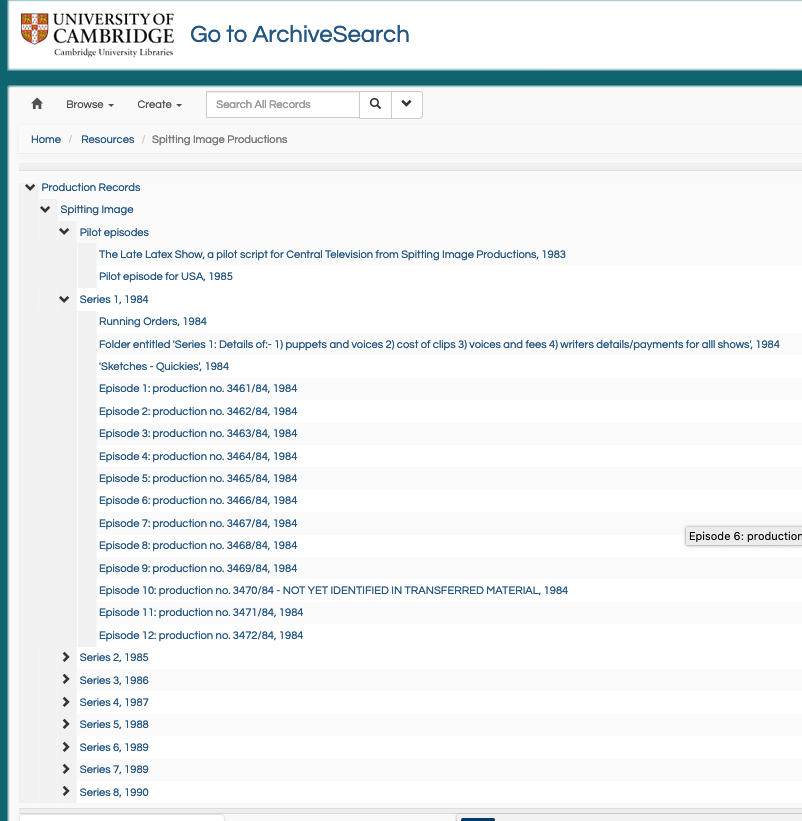

As the first section of the Spitting Image collection is about to be added to our new on-line catalogue, I thought it might be of interest to document some of the routine behind-the-scenes work that goes into making a collection available. I’m aware that going into the dull minutiae of the process may well make this the most boring blog post published by the UL!

It’s important first of all to stress that archive collections come in all shapes and sizes, from one item to hundreds of boxes. A collection may be well-organised, clean and not have any problematic legal issues. Alternatively, it could consist of binbags of miscellaneous, dirty, mould-infested papers (a blog post about the ‘ickier’ side of working with archives can be found here). Merely transferring a collection to an archive repository does not mean it is instantly available for research. Even the clean, well-organised ones take time to prepare and there are numerous processes, people and discussions involved in making them available. Luckily for me, Spitting Image is clean and well-organised (thank you Deirdre!) but there is still a lot of work needed before anyone can use it for research.

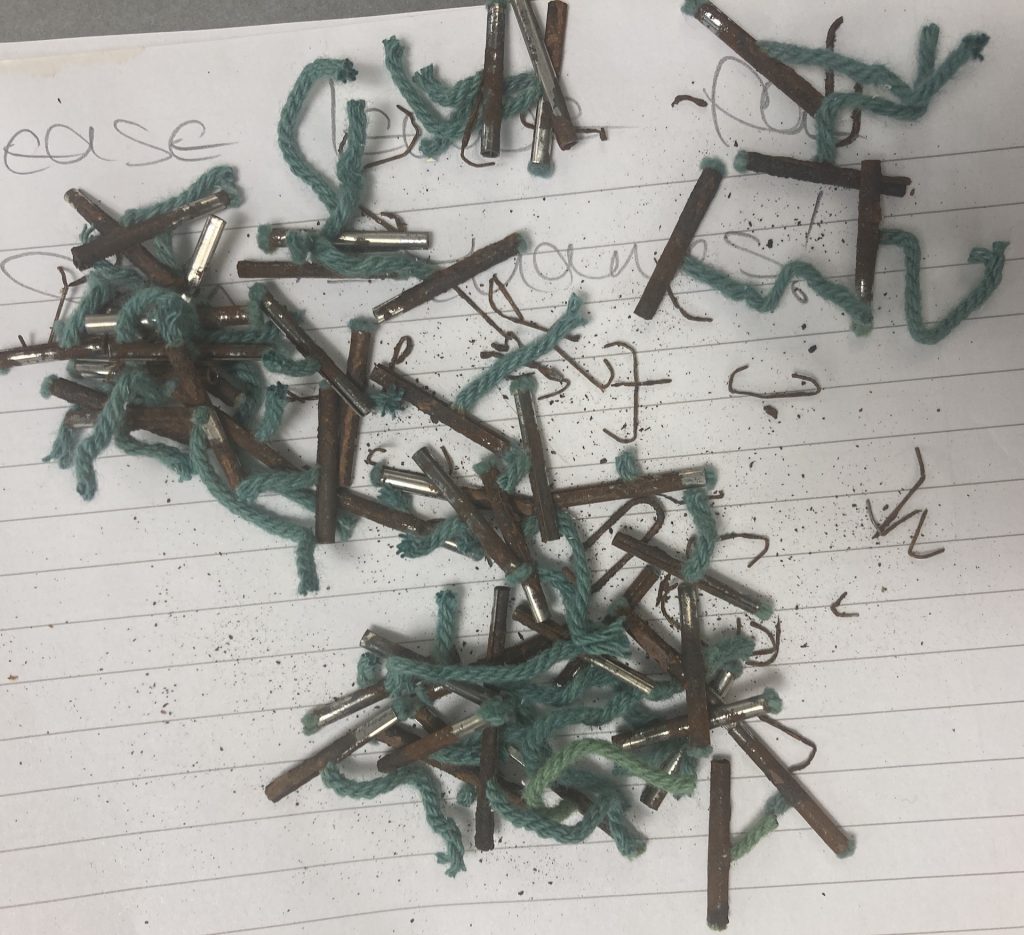

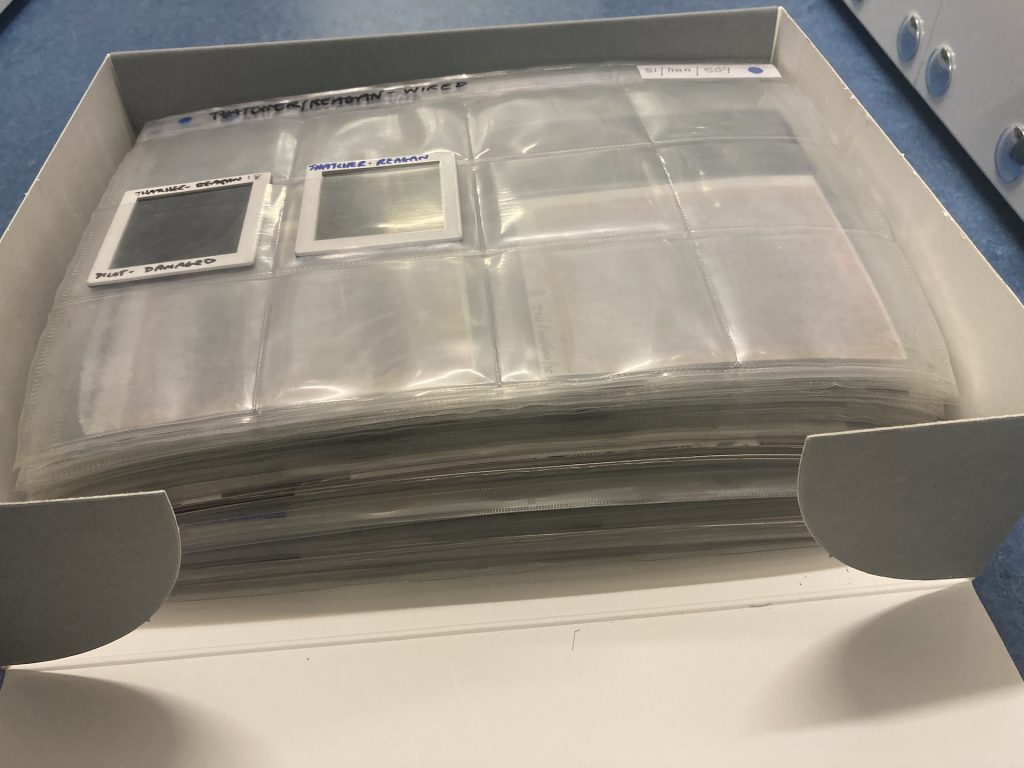

First of all, when the bulk of the records arrived last year they had to be quarantined to make sure that nothing inappropriate was transferred into our stacks. Once they were ‘released’, they were moved from their temporary location to the stacks and the contents of the transfer boxes put into more appropriate acid-free boxes. At all points of transfer, there has to be an accurate location/box list so we can identify where everything is. My least favourite task at this stage was removing sheets of transparencies from their metal hangers (they’d been stored in filing cabinets). By the end, there were hundreds of thin metal ‘things’ in a box and I had sore fingers! Before any cataloguing had even begun, significant time had already passed.

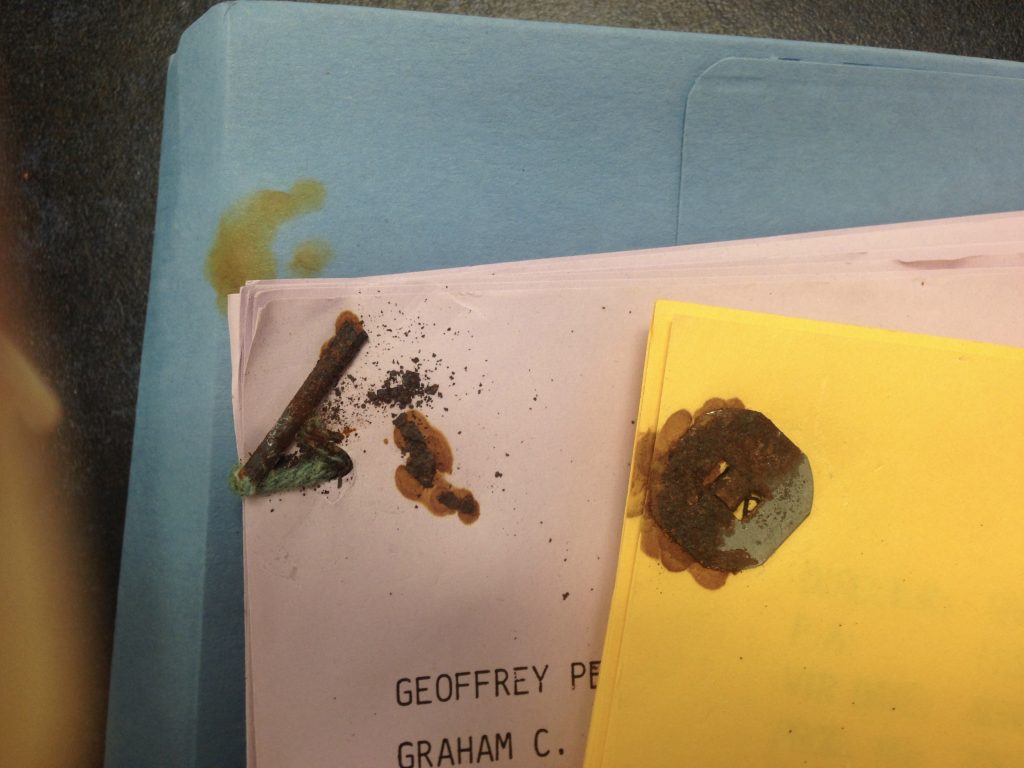

Records as they arrived

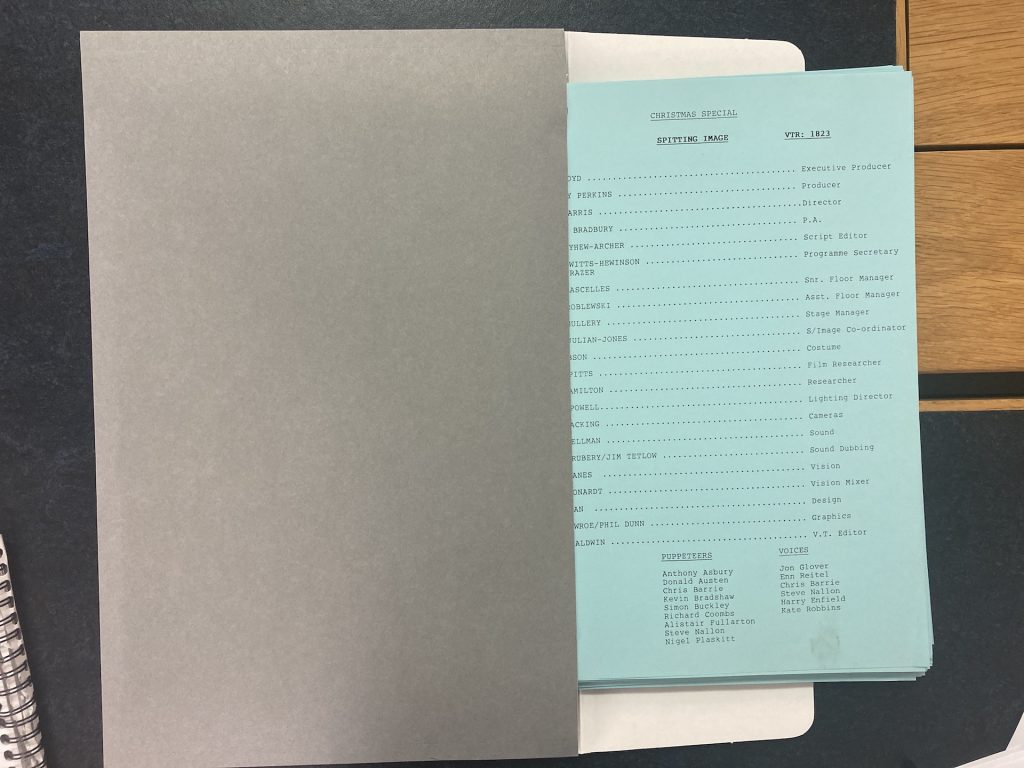

Records in acid free boxes

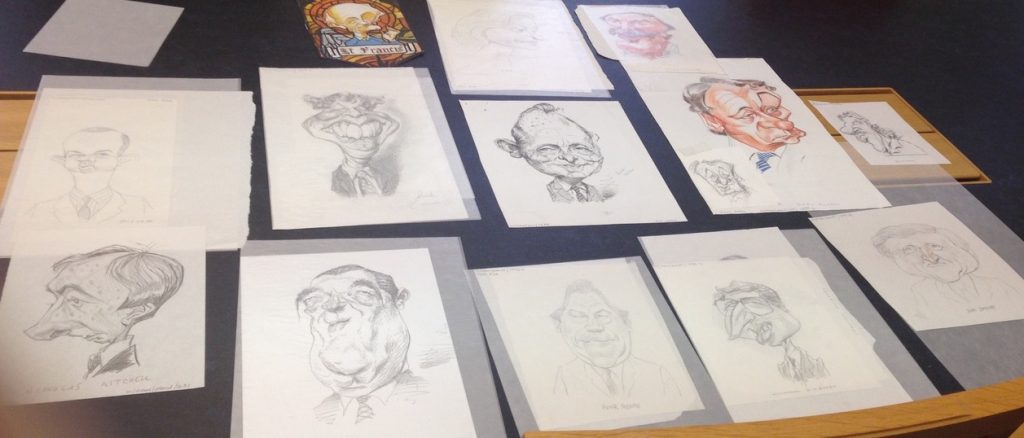

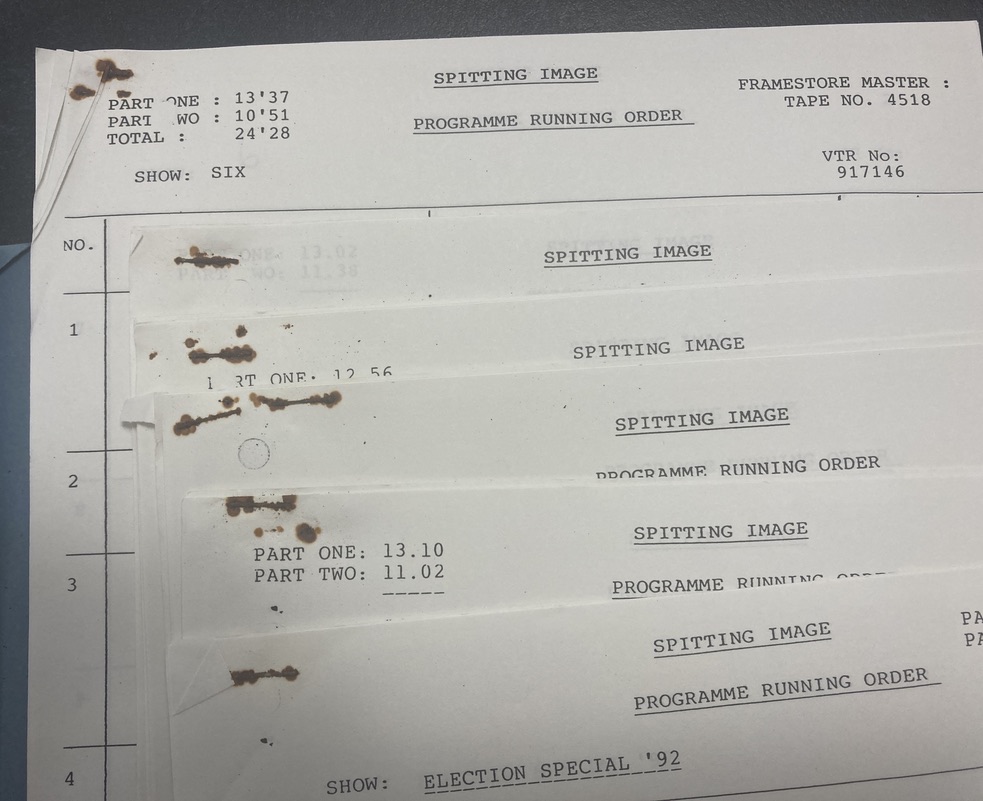

Due to the complexity of the collection, my focus has been on making the scripts available. They do not need much specialist knowledge to catalogue them to a high standard, which the thousands of drawings, caricatures and visual material do. All together, there are around 150 Spitting Image scripts. They were working documents so although they have been stored neatly and in chronological order, they arrived in a variety of packaging. The script bundles include different information so my first task was to get a feel for the content of the bundles so I could describe them appropriately in the catalogue.

The purpose of a catalogue is to let researchers see what is held and allow them to judge what might be of interest to them. A vital element of this process is the creation of a structure. A good structure can be the difference between a researcher finding information and giving up in despair! Archive catalogues are hierarchical and contextual, reflecting the original order of the creator and showing the relationships between the items. Developing a structure can be time-consuming for a complex collection as you have to understand how and when things were created. It’s also important to understand exactly what is in the collection before this work starts. I always say that getting the correct structure is similar to looking at one of those ‘magic eye’ pictures – all of a sudden it falls into place and makes sense! This initial work can take a while as archivists have to read through the material and do background research. Once this work is done, we have to analyse the records and write adequate descriptions, making decisions about what is important to note.

The content of an individual catalogue entry is vital. It is frustrating for researchers to order material only to find out it is not relevant to them. Also, it’s important to restrict the number of times that archives are transferred between areas that have different temperature and humidity levels. There is a very careful balance between providing enough information about each item and the seemingly ever diminishing time available to archivists. For Spitting Image I had to look through the scripts to get a feel for the content and to work out what information should be noted in the catalogue. I had to learn what a running order is, what a post-production script contains and what is meant by ‘banking’. It was only after all these processes that I finally sat down to create the catalogue content for the scripts, recording the content of each bundle and checking for various concerns.

As I mentioned previously, we are very lucky that the collection is in good condition. However, numerous documents do have metal fastenings that have rusted over the years. These need to be removed and this process usually takes place during the cataloguing phase. When a paper clip or staple is rusty, it is difficult to remove because it has to be coaxed out to avoid damaging the paper. It can take a couple of minutes to ease out each staple and some Spitting Image script bundles have up to eight metal fastenings. This process is frustrating, especially when cataloguing time is scarce with other, demand-led tasks taking priority. A small number were very difficult to remove so I had a discussion with one of our conservators about the best way of doing this. Although the ‘perfect’ method would be to repair and restore damaged paper, this is expensive and time consuming. My judgement is that the scripts were working documents and the use of metal fastenings is part of their journey. As long as information is not lost, tiny damage is acceptable. There is a school of thought that if items are stored in appropriate conditions with stable temperature/humidity, the metal should not deteriorate any further and does not need to be removed. I believe – as do many conservators – that this is too much of a risk.

So many staples….

A small number of the treasury tags removed

This one’s going to Conservation!

As this is a modern collection we need to be aware of data protection issues around personal information in the script bundles. Many of the bundles contain contact details and fees paid to writers and others. Although it is doubtful that these contact details are current, we have to be careful. It is unlikely that disclosure of the fees paid without the consent of each person would be in line with GDPR so I have to consider what to do with that information. Some of the scripts have this information in a separate bundle so the script can be looked at without worry. For other scripts, the information is within the bundle, which means I have to look through the entire bundle to identify problematic material. I have chosen to remove documents that include this information and make a note that I have done so. This will allow us to produce the script without worry. However as these are working documents, it’s also important to check for handwritten comments or notes that might not be suitable for disclosure. We also need to think about copyright and licensing issues and decide – with the permission of the depositors – whether to allow photography or reproduction of the contents of the collection.

During the cataloguing process, items are transferred into appropriate archival packaging. I have put the scripts into acid free folders and in order to do this most efficiently, I had to identify the correct size. Sometimes this process means having to source and order new folders so they fit in boxes that make the best use of space – another mundane but important task. In many collections, as you work your way through it, the new packaging means that items no longer fit into the boxes they were put into. This leads to more physical rearrangement and shuffling around, all of which takes yet more time.

Finally, the scripts have to be clearly numbered when they have been assigned their place in the hierarchical structure. Numbering will only take place at the end of the process once I’m sure that everything is in the right order and there is nothing missing. It is very irritating to find something that should have been catalogued in an earlier series!

An issue (possibly unique to Spitting Image scripts) that only occurred to me recently is linked to making the scripts available in the Reading Room. We are similar to most archive services in trying to maintain a quiet Reading Room. Researchers may not have long to work through what they have come to see or they might be looking at complex information or records that contain faded, nearly illegible handwriting. Therefore it is important to keep disturbances to the minimum. Reading parts of the scripts since they arrived has caused me to laugh out loud. This reaction can be unforeseen and involuntary – and very irritating to those around me! I will need to discuss with Reading Room colleagues how we can make this material available without compromising other readers’ need for quiet. At the time of writing, I don’t know what the answer will be!

Squeaky dog chews!

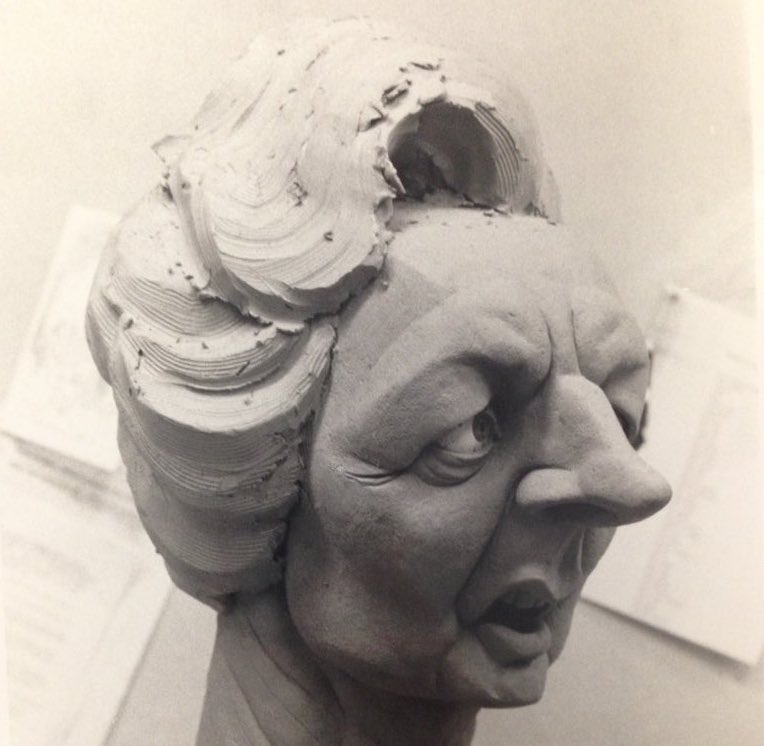

Photograph of clay head

A small selection of transparencies

The work I’ve described here is for what is probably the most straightforward section of the collection. The visual material (including transparencies, drawings, caricatures) will need careful and considered work around appropriate storage, packaging and description. Discussions will take place between me, Conservation and our Digital Content Unit about the best way of caring for these items. All of the cataloguing stages are time-consuming and many of them are physical and tedious but they all need to be completed before a collection can be safely and securely made available in the Reading Room. I hope this post has provided some insight into why that process can sometimes take a little while – and I hope some of you are still awake!