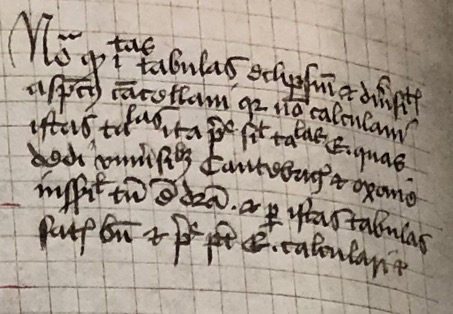

An astronomer’s personal notebook: Lewis of Caerleon & CUL MS Ee.3.61 (Part 2)

Dr Laure Miolo is a Munby Fellow in Bibliography at Cambridge University Library. As part of her project, she is working on Lewis of Caerleon’s extant manuscripts and astronomical works, and more particularly on his notebook, MS Ee.3.61. This post follows on from an earlier one, which can be found here.

‘While in the Tower of London, I observed the solar eclipse that occurred in the year of Lord 1485, after midday, the 16th March’. These are the words of the astronomer and royal physician, Lewis of Caerleon (d. c. 1495) who refers to the observation he made from the prison where he had been incarcerated by order of Richard III. This mention is written at the bottom of his detailed computation of this same solar eclipse which is preserved in two extant manuscripts, one of them being held in St John’s College, Cambridge (St John’s College MS (41) B19). Both this note and the computation are representative of interests Lewis developed earlier in his career and copied in his notebook. As discussed in the previous blogpost, CUL MS Ee.3.61, was an important sourcebook for the astronomer, and it is also there that he recorded the earliest stages of his own astronomical works.

An astronomer at work

Lewis of Caerleon’s notebook is not a mere compilation of previous astronomical and astrological works, it is also the place where he copied some of his own productions. His treatises and tables clearly show his interest in eclipse phenomena which was one of the main concerns of medieval and early modern astronomers and astrologers.

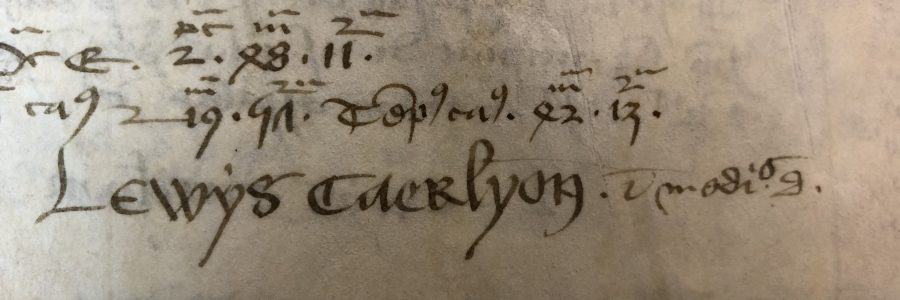

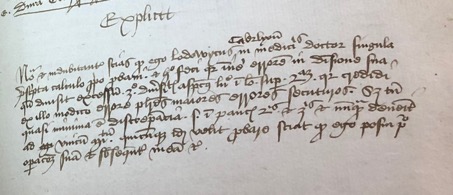

(1) Lewis of Caerleon’s lunar parallax table based on the Oxford meridian, said to have been calculated according to the Albion, Ee.3.61, f. 151v.

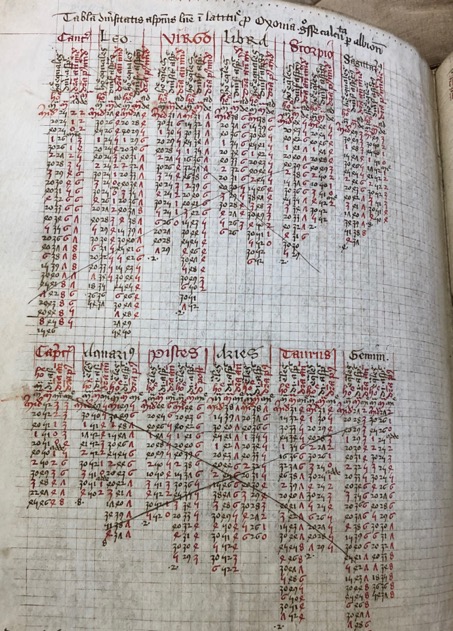

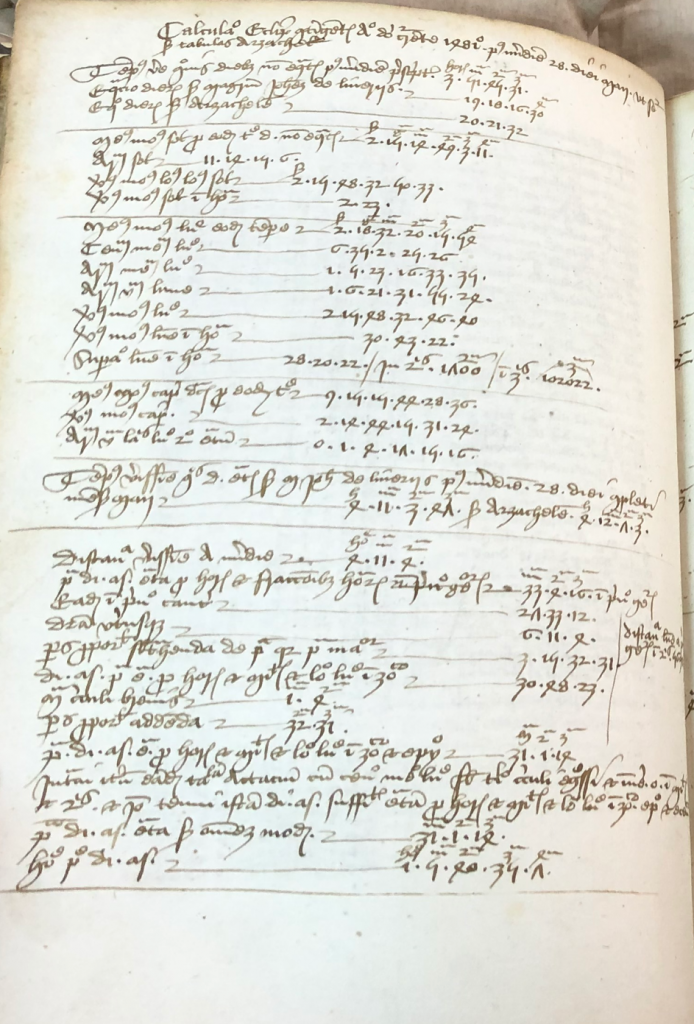

(2) Lewis of Caerleon’s solar eclipse table, Ee.3.61, f. 147v.

The way to predict an eclipse (that is a true conjunction or opposition of both luminaries) and to calculate its magnitude and duration represent a complex mathematical exercise which requires a real expertise and calculating skills. Two steps of this kind of computation were particularly demanding: the determination of the time of true conjunction or opposition of the luminaries, and the calculation of the parallax (here, the correction between the apparent position of the moon and its true position for an observer situated at a specific location on Earth). Indeed, the computation of the lunar parallax was one of the major challenges of medieval astronomy. Lewis of Caerleon was interested in eclipse computations and more particularly in the parallax problem as well as in the magnitude and the duration of eclipses. For this purpose, he created new parallax and eclipse tables and he wrote astronomical canons in order to explain how to perform these calculations by means of his own tables. In addition to this, he was also fully involved in trigonometrical problems and spherical astronomy. He drew tables of sines and chords as well as tables of oblique and right ascensions.

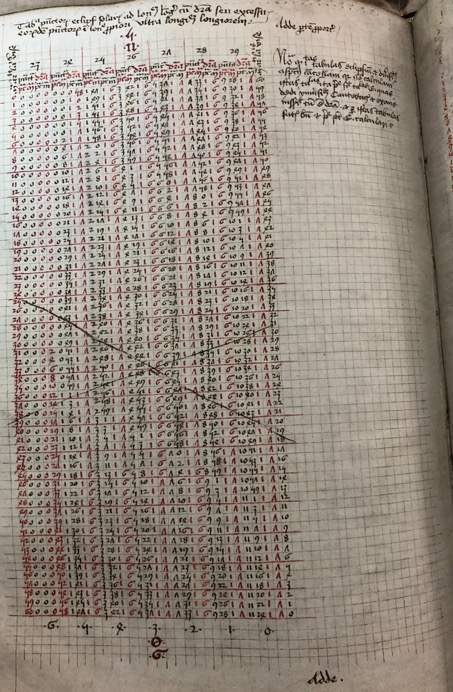

His thorough astronomical knowledge and his compilation of tables made him one of the key actors of the renewal of trigonometry, spherical astronomy and eclipse computation in England. Although he does not seem to have had access to the work of the astronomer Regiomontanus (d. 1476), who was almost his contemporary in Italy and a leading figure in the field, Lewis of Caerleon developed an innovative and ambitious research agenda related to eclipse computations and spherical astronomy mainly based on geometry and trigonometry. His notebook contains the tables and works he composed between 1481 and 1482/83. It can be divided between tables, theoretical works (that is, canons) and eclipse computations. Amongst the tables composed and copied by Lewis of Caerleon in his notebook are lunar parallax tables based on the Oxford meridian; eclipse tables; tables of elongation (distance between the true position of the sun and the moon – see image 1 above). Although Lewis of Caerleon created several sets of tables based on the meridian of Oxford, London or Cambridge preserved in other extant manuscripts, the notebook only contains an early set designed for the Oxford meridian. However, he came back later to this primitive set after it was copied and crossed it out. The reason for this deletion is clearly mentioned in the margin: the eclipse tables he gave to the universities of Oxford and Cambridge were computed more precisely than these earlier ones (see images 2 & 2a above and right).

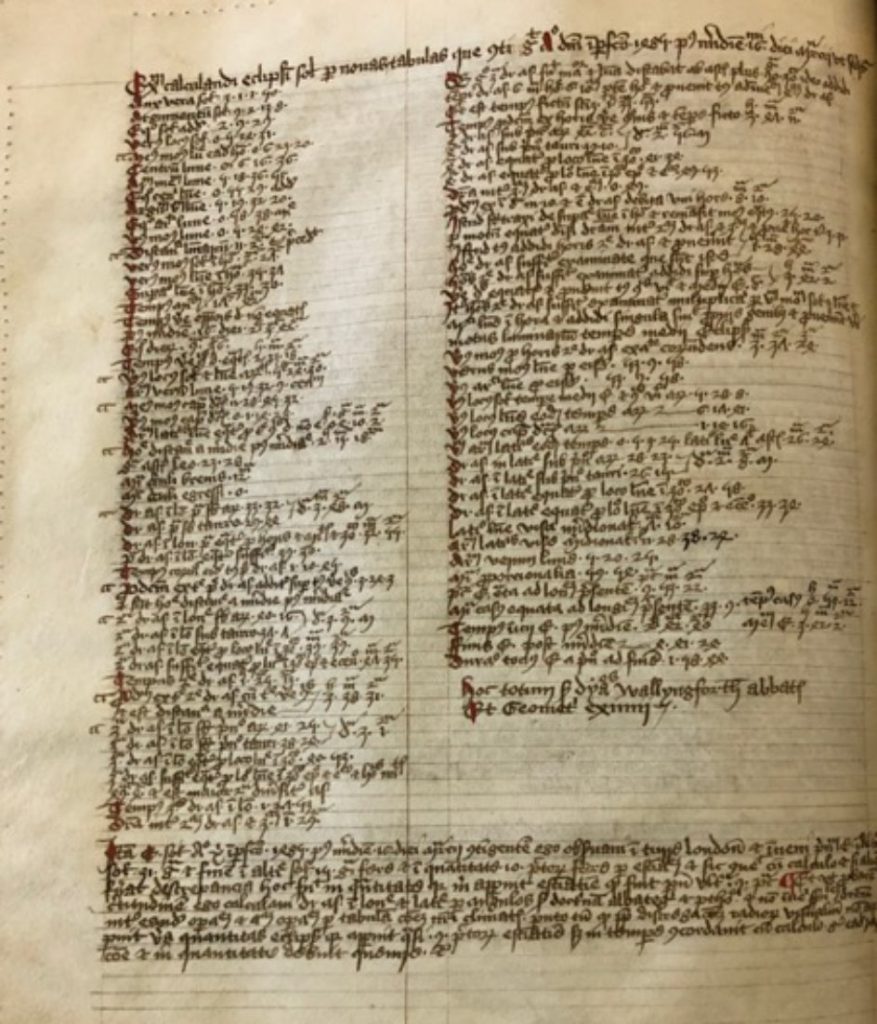

Amongst the notes and short texts associated with these tables, there are the eclipse canons which explain how to compute a solar or a lunar eclipse with the help of the ‘new tables’ (nove tabule) he elaborated. The output of the tables and canons is the eclipse computation. Lewis of Caerleon copied (and corrected!) some previous computations as exempla, such as the computation of the solar eclipse of 3 March 1337 by John of Genoa, active in Paris in the 1330s (see image 3 below). But Lewis also provides computations of two partial solar eclipses respectively occurring on 28 May 1481 and 17 May 1482 (see image 4 below). The calculation of the eclipse of 1481 is detailed and was done according to different tables, including Lewis of Caerleon’s own early eclipse set. These computations illustrate the astronomer at work seeking the most accurate sources and tools to compute a celestial phenomenon.

(4) Computation of the solar eclipse of 28 May 1481, Ee.3.61, f. 12v.

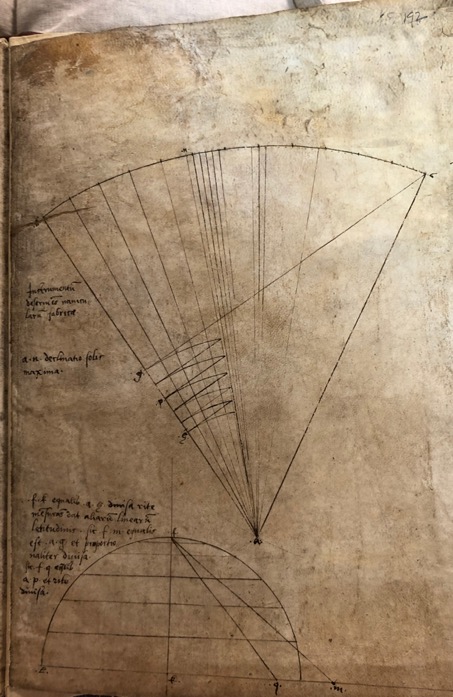

(5) Drawing of the navicula, Ee.3.61, f. 192r.

Posterity

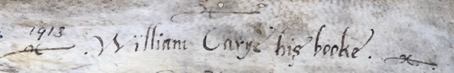

This unique manuscript attracted the attention of later owners who were also experts in astronomy/astrology, or antiquarians. A 16th-century English anonymous annotator, well-versed in astronomy is responsible for various additions written on blank spaces or folios, such as a prediction of the end of the world (planned for the year 1765), excerpts from the Almagesti minor (an early anonymous Latin commentary of Ptolemy’s Almagest) or diagrams related to the portable sundial called a navicula at the end of the manuscript (see image 5 above). A signature on the verso of the second flyleaf, that reads ‘William Carye his book’ demonstrates that the volume was once in the hands of this cloth-worker of St Mary Magdalen parish in London (see image 7 below).

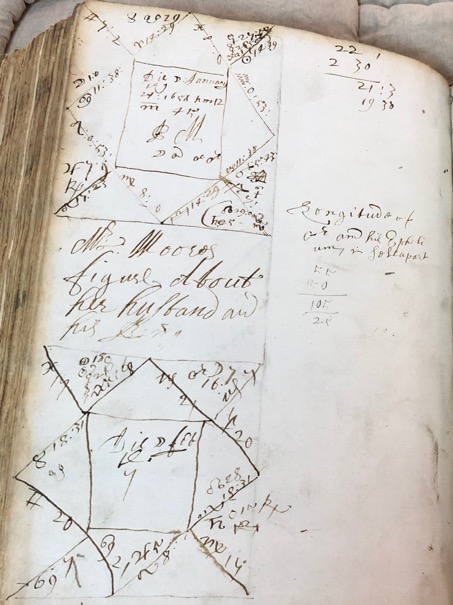

William Carye (d. 1572/3) is known as a collector of medieval manuscripts. Then, Lewis of Caerleon’s notebook passed to another practitioner whose signature can also be read in the volume. Richard Jones drew five horoscopes on leaves originally left blank. These horoscopes are dated 1658 and 1659 and were cast for ‘Mrs Moores, figures about her husband and his being’ (see image 8 below). Almost two centuries after Lewis of Caerleon, who practised astronomy and likely astrology, this book was acquired by an astrologer. It is worth underlining that there is no family link between Mrs Moores, the commissioner of the horoscopes, and the next known owner, John Moore (d. 1714), bishop of Ely. The manuscript was acquired by Moore during his time as bishop of Norwich between 1691 and 1707. On Moore’s death, the entirety of his library was offered to Robert Harley, earl of Oxford, who refused it. It was eventually purchased by King George I, who donated it to the University Library in 1715.

Bibliography

Pearl Kibre, ‘Lewis of Caerleon, Doctor of Medicine, Astronomer and Mathematician (d. 1494?)’, Isis, 43:2 (1952), 100-108.

John D. North, Richard of Wallingford. An Edition of his Writings, 3 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1976), III, pp. 217-20.

Andrew G. Watson, ‘Christopher and William Carey, Collectors of Monastic Manuscripts, and “John Carye” ‘ , The Library, 5th series, 20 (1965), 135-42.