Word & image in a sixteenth-century prayer book

We all put things in books. Whether it’s bookmarks (old train tickets, receipts or some other bit of paper no longer required), related ephemera (magazine cuttings linked to the subject of the text, perhaps) or even food, as discovered by one of my colleagues in a sixteenth-century book recently. Readers of books in the early modern period were no different, and librarians often find letters, images and flowers carefully slipped or pasted into books which – long ago – made their way onto institutional shelves, revealing something of their provenance, or personal history. Just such a thing happened to me recently.

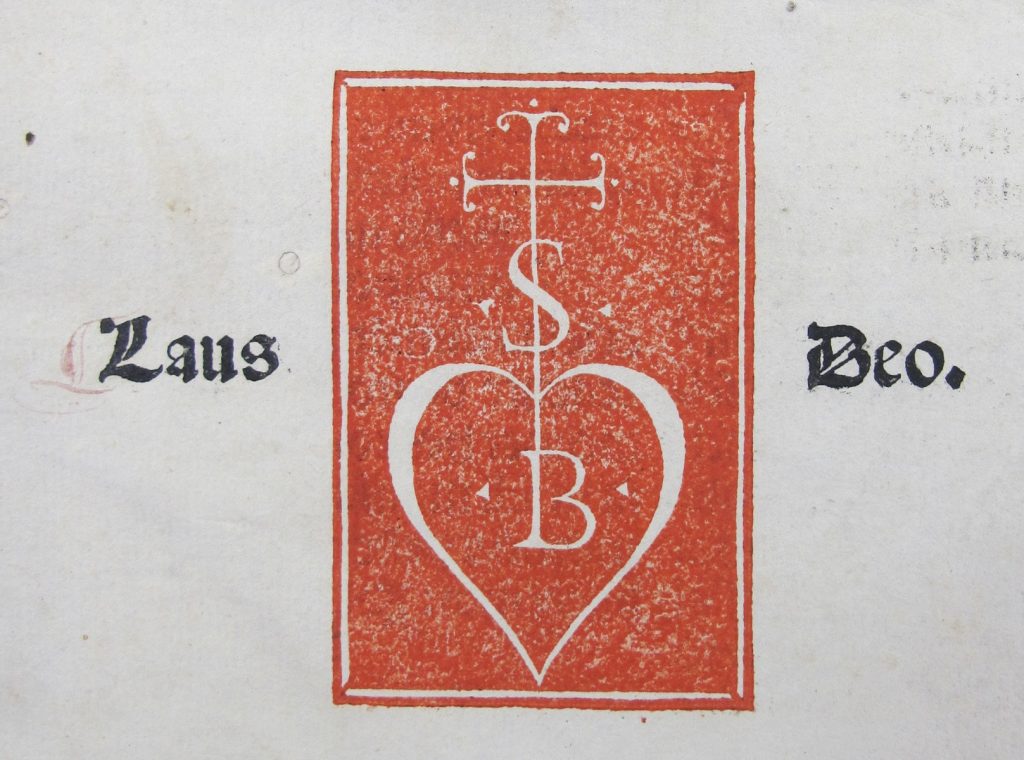

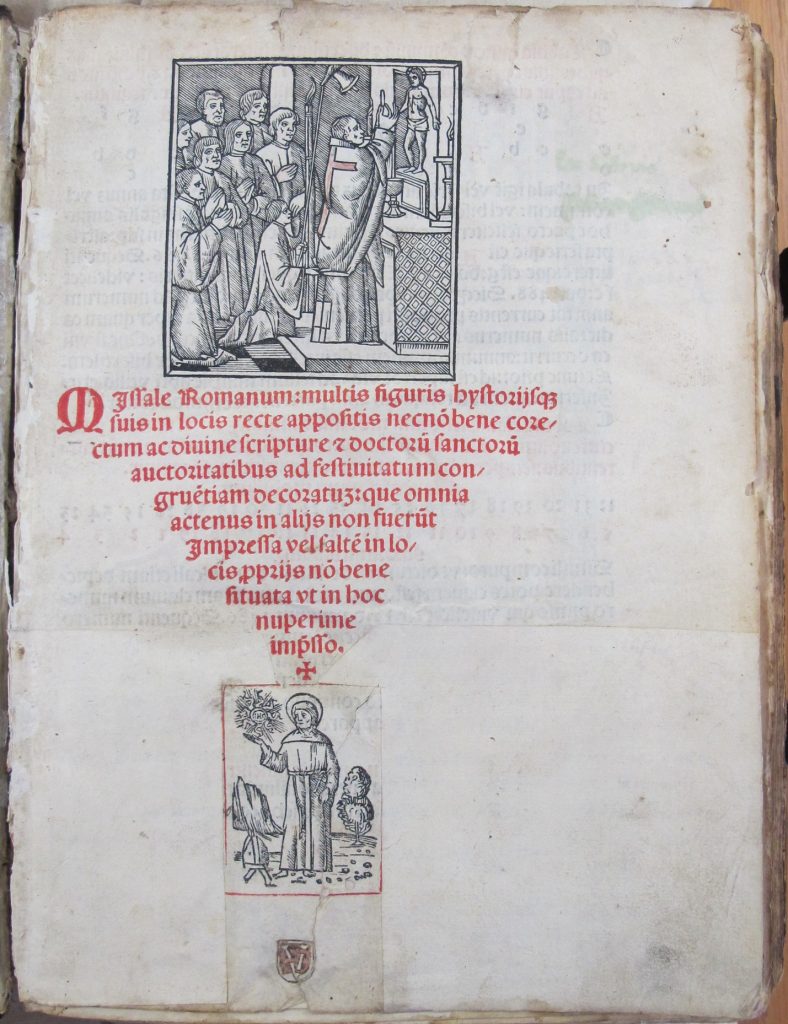

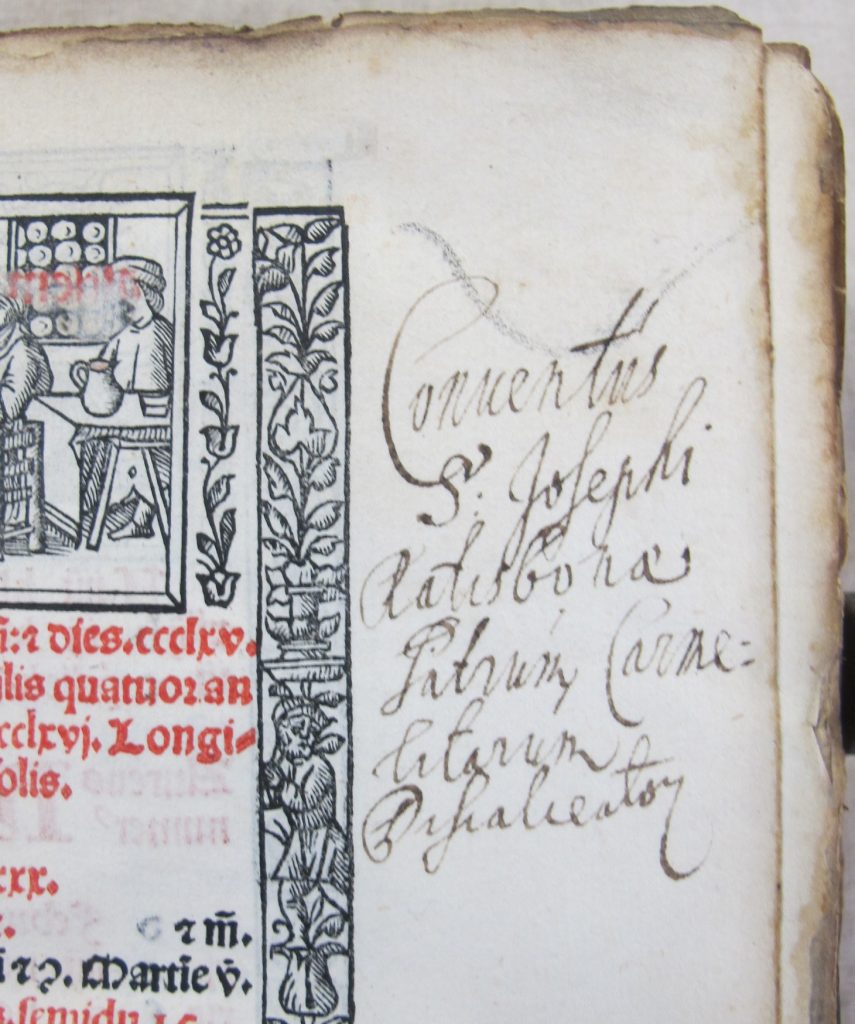

As I fetched from the shelves an early sixteenth-century Missal (shelfmark F150.c.2.11) – a devotional text giving the prayers to be used during the service of Mass – I was struck by the early binding on the book. Printed in Venice by Bernardino Stagnino in 1509, the book appears to have made it way to Germany not long after publication, given the style of the binding (stamped pigskin, with metal clasps – see image above left) and the nature of the stamps used to decorate its boards. These include a circular stamp of an eagle (possibly the symbol of the evangelist St John) and a diamond-shaped stamp of a flower. Venice was, in the early sixteenth century, the centre of printing in Europe, and the books printed there were traded in many directions. This early move to Germany is supported by an inscription (probably seventeenth century: see below left) on one of the early pages of the book: ‘Conventus S. Josephi Ratisbona patrum Carmelitarum’. This is the Carmelite monastery of St Joseph in Regensburg (in Bavaria), in operation from 1635 until its closure under secularization in 1810 (though it would reopen in 1836), whose buildings survive today.

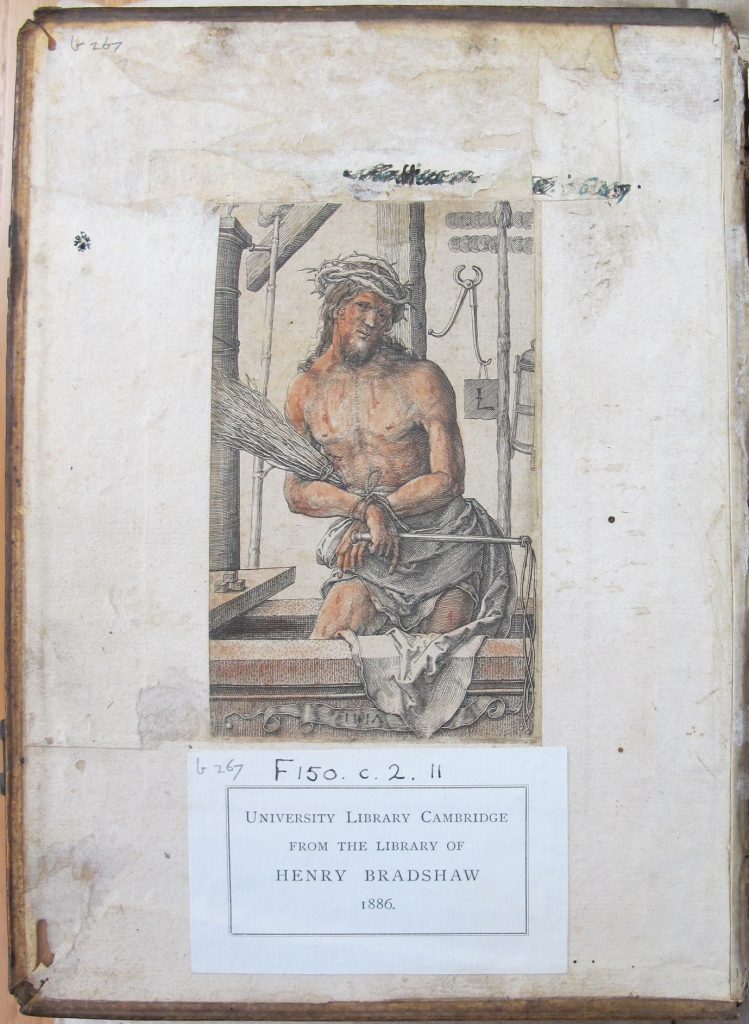

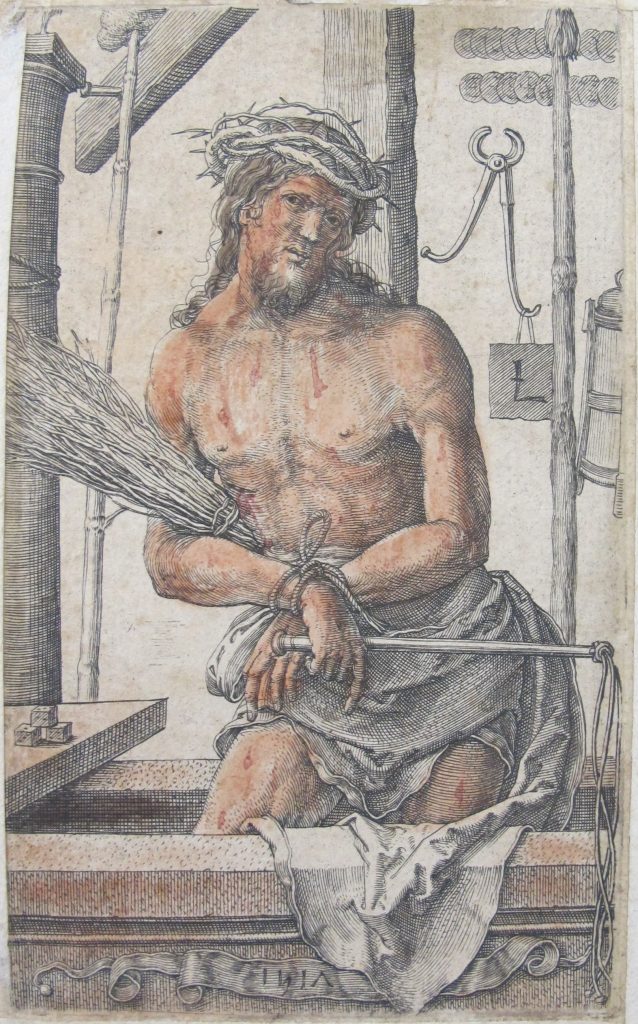

But it was an image pasted to the inside front cover which was most interesting (above right): Christ as the man of sorrows, with the instruments of his passion (crucifixion). I guessed that the ‘L’ hanging below the pincers in the right of the image was the artist’s signature, but not having any clue as to their identity I took to Twitter to see if anyone might be able to help. Within five minutes I had an answer from Michael Pearce identifying the artist as Lucas van Leyden and giving a link to a copy in the British Museum. Van Leyden, as his name suggests, was born and worked in the Netherlandish city of Leiden (between Amsterdam and The Hague). He died in his late thirties (in 1533) but in a short time became one of the most prominent Netherlandish artists, working in diverse media including engraving (as here), panel painting and stained-glass design. Seventeen of his panel paintings are known to survive, including a portrait of a man at the National Gallery. But his engravings travelled much more widely and between 1513 and 1517 he created a series known as ‘The Power of Women’, which used historical and mythical imagery to portray the superiority of men over women. Hundreds of copies were produced from each engraved plate and could be sold far more cheaply than paintings. This meant they could be acquired by people of more average means, and might be stuck up on walls in their homes or pasted into books, as here.

NG2593 (Wikimedia Commons)

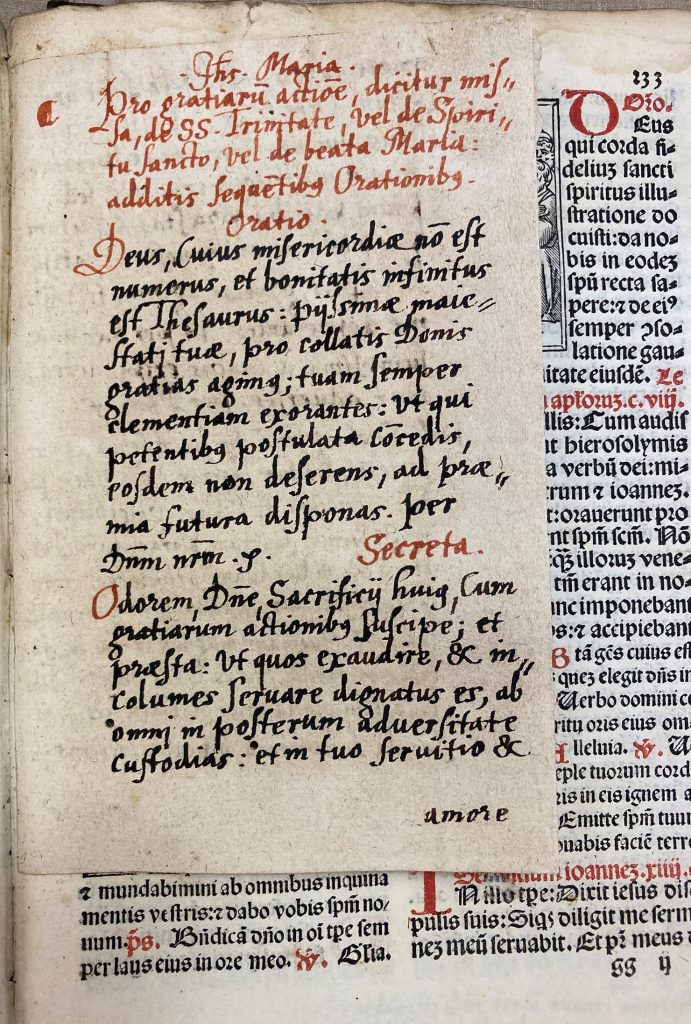

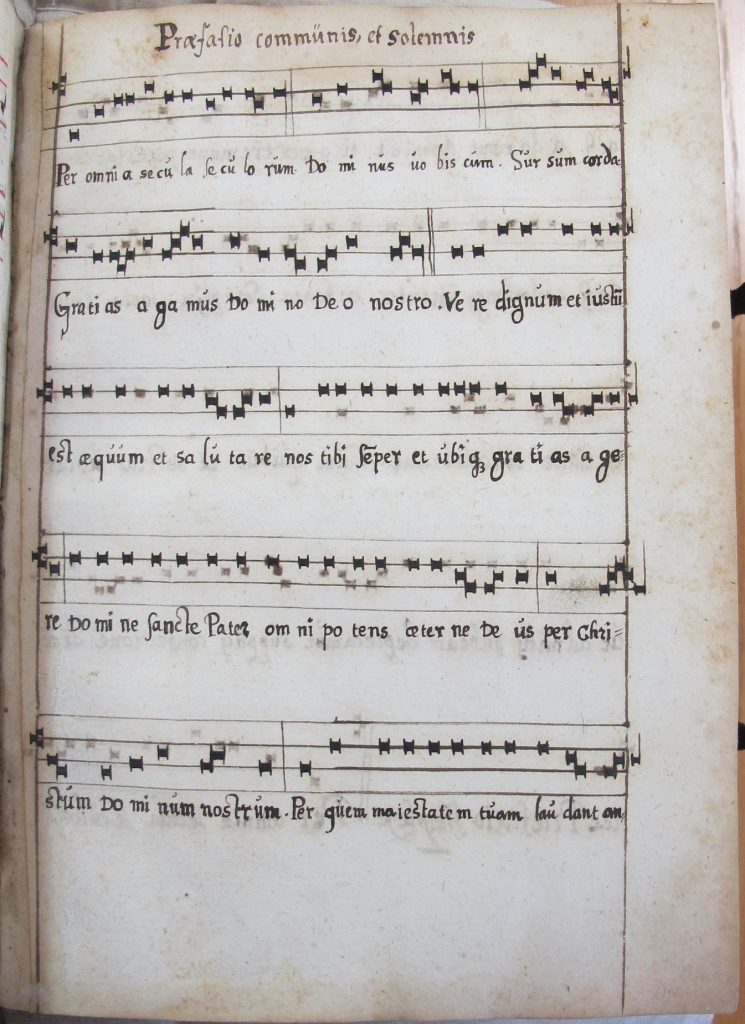

Both aided private devotion and as we see in the picture above left (a fifteenth-century example by Petrus Christus at the National Gallery, showing a hand-drawn image on parchment on the wall rather than an engraving) single-sheet devotional images could be used in conjunction with a prayer book. Perhaps our image was hung up in the home, and later pasted into the book for safekeeping. The book has evidently been heavily used during its long life and a number of printed leaves are missing, having been replaced with manuscript copies, as in the example above right of manuscript music. It is not known where these were executed, but the end of the series of added leaves once bore a now erased inscription whose date – 1605 – can still be read.

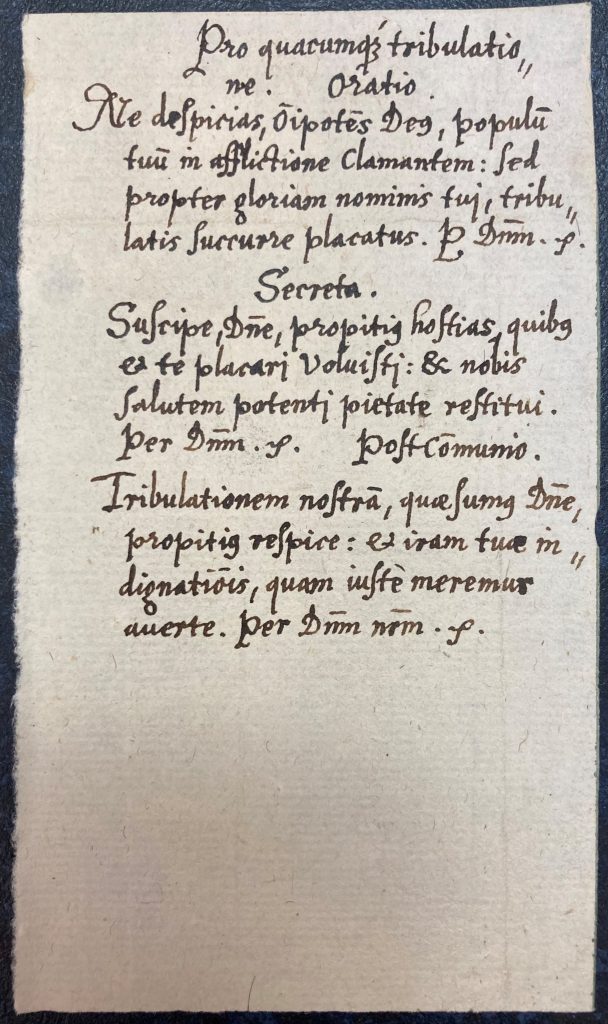

Other things have been added to the book, including two slips of paper containing prayers – one loose and one pasted in – in the same handwriting. These features – manuscript music, handwritten prayers and evidence of the links between word and image in early modern devotion – would no doubt have delighted the book’s nineteenth-century owner, Henry Bradshaw (1831-86). Bradshaw was University Librarian at Cambridge from 1867 and liturgical books were one of his chief interests. The Henry Bradshaw Society was founded shortly after his death, to publish editions of liturgical texts, and in 1911 some of the books he’d left to the Library (including this Missal) were gathered in a new class known as ‘Rit‘ (for ‘Ritual’), where they continue to reside.

It is thanks to Bradshaw’s eagle eyes, seeking out interesting and rare material like this, that the Library has such rich holdings in this area, and this example shows just how easy it is to bring out hidden and unknown stories from books on our shelves.