The abandoned library

On 7 May 1921, a hundred years ago today, the University of Cambridge took a momentous decision. After decades of debate and controversy, it finally resolved to abandon the cramped, chaotic and overcrowded medieval site of the University Library in the middle of the city next to King’s College Chapel, and build a new place for books west of the river. It was a close-run thing: the arguments for and against were still being contested up to the last minute, but the final vote showed a clear majority in favour of the move, with 121 votes for and 73 against.1

The Library – like all libraries – had always struggled with lack of space, but this had become increasingly difficult in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Various schemes were proposed for the existing site: build another extension, build underground, roof over the courtyards. An offsite store was also considered. In the end, a clean cut was made, laying the foundations for today’s library, Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s magnificent, monumental machine for reading books in.

Yet alongside the thrill of the new, the removal of the Library left a hole as empty space in the medieval buildings at the heart of the University and, for some, a figurative hole that was experienced as a profound sense of loss.2 For all its flaws and failings, it was held in great affection and the loss of the site continuously occupied as the University Library for over 500 years cut deeply. It was an ‘abandonment’, and even those who knew it was necessary – perhaps especially those – shared this pain. Three days before the vote in the Senate on 7 May 1921, the University Librarian Francis Jenkinson answered the opponents of the move in powerfully understated terms:

The mere thought of abandoning the old site is not less painful probably to us who spend our lives there than to any of those who oppose the scheme. But in a generation that will be forgotten. When a step is to be taken, it is good economy to take it at once.3

In the end, though, it was a long goodbye. A new site had to be found and funds raised. A decade passed before the first piles were driven into the ground in West Road in 1931 and three more years before the Library opened to readers. Jenkinson, who was already sixty-seven when the vote took place in the Senate, didn’t live to see the new library; he died just over two years later in September 1923. Nor did Hugh Anderson, Master of Gonville and Caius, who secured funding from the Rockefeller Foundation for half the costs; nor Jenkinson’s Under-Librarians, Charles Sayle and Theo Bartholomew, who died in 1924 and 1933 respectively. The report of the opening of the new library in The Observer reflected on this:

Amidst to-morrow’s stately ceremonies the thoughts of some may well revert to Cambridge bibliographers of the recent past – to Francis Jenkinson … to Charles Sayle … to Theodore Bartholomew … These and many other well-loved servants of the Library might well be amazed at the consummation to which they in their time, looked wistfully forward.4

The report in The Star also sounded a note of regret for the old place: ‘… for many years professor and student will look wistfully at the older building’.5 This cut deeper than nostalgia, and went beyond ‘a reverence for the past’. To use the words of Dr Jessica Gardner, today’s University Librarian, it reminds us that libraries are ‘profoundly people places’, and that a sense of place is part of what makes a library so special to the people who use it.6 You can move a collection of books – and that is exactly what the staff of the Library did in 1934: one-and-a-half million volumes, 23,725 boxes, 689 lorry-loads, 18-van-loads of large bound newspapers and elephant folios ‘too big for any box’; over eight weeks from 1 June to 26 July, book after book left the Old Library and travelled west across Cambridge until no more books were left – but you can’t move a library.

In the decades that followed, the University Library enjoyed the pleasure and pathos of a 500-year-old institution in a new building, but it didn’t forget its former home. In 1959 and 1974 receptions were held to mark the 25th and 40th anniversaries of the move.7 In 2001, the Library recorded with great regret the death of Arthur Tillotson (1908–2001), believed to have been the last surviving member of the Library staff who had worked in the Old Library, who had retired as Secretary of the Library in 1975. The beautiful sweet gum trees at the front of the building were planted in his memory.

Today, a hundred years after the momentous vote of 7 May 1921, as we celebrate the starting point of Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s big, beautiful brute of a building, it feels right to pause and be grateful to those who worked so hard to secure the future of the Library, and who in doing so had to abandon something they loved.

Notes

- Cambridge University Reporter, 1920-21, p. 959.

- See, for example, the speech at the reception to mark the opening of the new library by M. R. James, who commented that ‘wisdom will not expect the men of my generation or of several later ones to leave without a sore pang of regret the old home’. ‘M. R. James and the ghosts of the old University Library’, https://specialcollections-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/?p=18923.

- Francis Jenkinson, ‘The needs of the Library: a marginal note’, 4 May 1921, ULIB 9/4/2.

- The Observer, 24 Oct 1934.

- The Star, 16 Oct 1934.

- Jessica Gardner, ‘Owning the past, seizing the present’, Oxford Library 700 Conference, 17 Sept 2020.

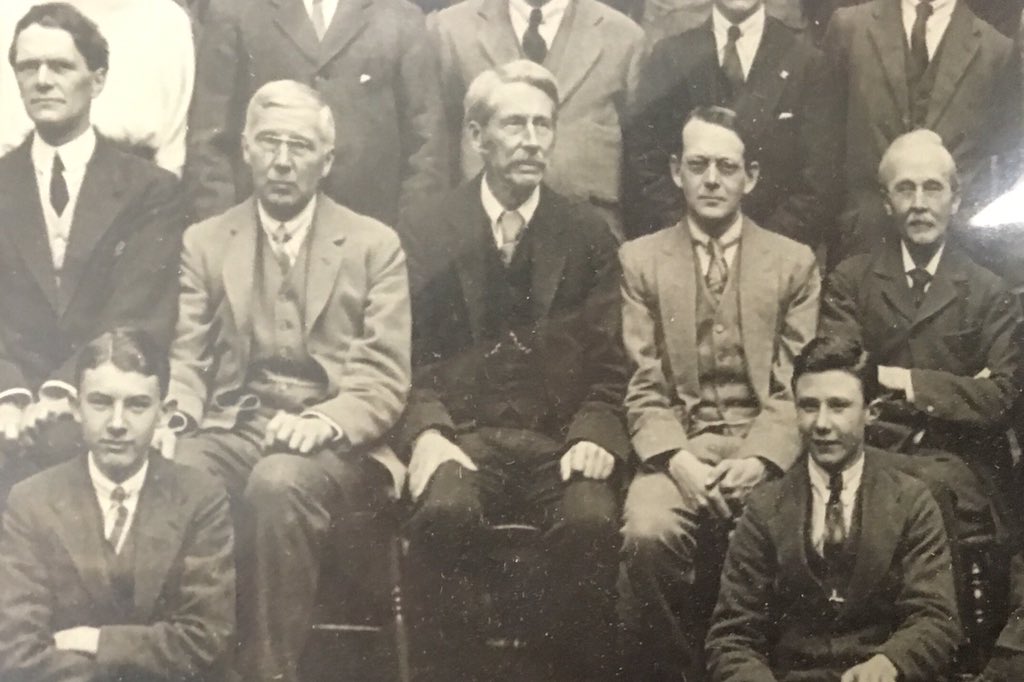

- See the photographs in the University Library Archives at ULIB 12/2/16 and 12/2/22.