A new acquisition from Gabriel Harvey’s library

The Library holds many books formerly in the possession of significant historical figures. Other than the simple pleasure of knowing that a book was once held by people like the Elizabethan polymath John Dee, the great seventeenth-century scientist Isaac Newton, or the twentieth-century campaigner for women’s rights Marie Stopes, books from the libraries of these figures can tell us much about their inner thoughts as they read. One such figure is the sixteenth-century Cambridge academic Gabriel Harvey, well known for annotating his books, and the Library is very pleased to have added a book from his library to its shelves in the last month or so: a 1568 edition of Henri Estienne’s work on the Greek writers Sophocles and Euripides. Harvey (c. 1552/3—1631) was born in Saffron Walden (about fifteen miles SW of Cambridge) and studied at Cambridge in the 1560s and 1570s, matriculating as a pensioner at Christ’s College in Easter term 1566, taking his BA in 1569/70 and serving as a fellow of Pembroke from 1570 (from where he took his MA in 1573). In 1578 he became a fellow of Trinity Hall, having decided to take up the study of the law, and took an LLB there in 1585. In the same year he was elected Master, only to have the offer withdrawn on the suggestion of the Vice-Chancellor Andrew Perne, after a disagreement between the pair in 1577. This concerned Harvey’s ownership of precious books from the library of his mentor, Sir Thomas Smith of Saffron Walden (who got Harvey his fellowship at Pembroke in 1570), which had been coveted by Perne himself but were instead presented by Smith’s widow to Harvey.

Harvey’s life seems to have been beset by controversy; at Pembroke in 1573 his admission as a Master of Arts was blocked by a group of fellows headed by the future Dean of Canterbury and Master of Trinity, Thomas Nevile, who objected to his arrogant and unsociable demeanour, and for many years Harvey traded blows in a pamphlet war with the poet and satirist Thomas Nashe, fifteen years his junior, who was admitted to St John’s in October 1582. This eventful life was evidently a productive one, both in terms of literary output and friendships. He published several works, including his Cambridge orations, given 1574-76 and published as Rhetor and Ciceronianus in 1577 (the latter held that oratorical style – like Cicero’s – must come from a broad understanding of all fields of knowledge), a tribute to his deceased patron Sir Thomas Smith (Smithus; vel Musarum lachrymæ, of 1578) and a volume of Latin verse (Gratulatio Valdinensis, 1578) which had been presented in manuscript form to Elizabeth I and her courtiers at Audley End in July that year. He was a friend of Edmund Spenser, also at Pembroke, and appeared as Colin Clout’s ‘especiall good freend Hobbinol’ in Spenser’s The Shephearde’s Calender.

This literary life led to the formation of a substantial library, estimated to have numbered perhaps 1200 volumes. Of these only about 160 survive in libraries today (of which five are now at the University Library and another 10 or so in the college libraries at Trinity, St John’s, Pembroke, Magdalene and Emmanuel), and his ownership of another 40 or so has been inferred from references in his writings (noted in Virginia Stern’s 1979 study of his library). The contents of Stern’s survey have been improved by more recent studies, and a spreadsheet listing all known books is currently hosted online. In 1990 Harvey’s reading habits were the centre of a study by the late Lisa Jardine and Anthony Grafton (published in Past & Present as ‘”Studied for Action”: How Gabriel Harvey Read His Livy’) and today fourteen of Harvey’s heavily annotated books are fully digitised on the Archaeology of Reading site, bring Harvey fully into the age of digital humanities.

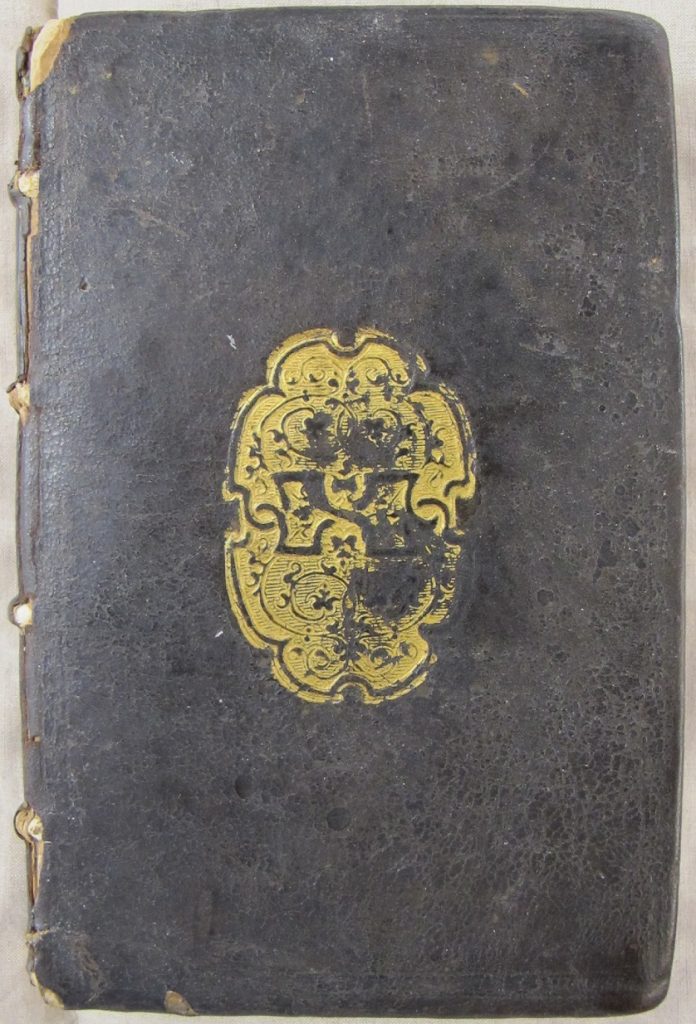

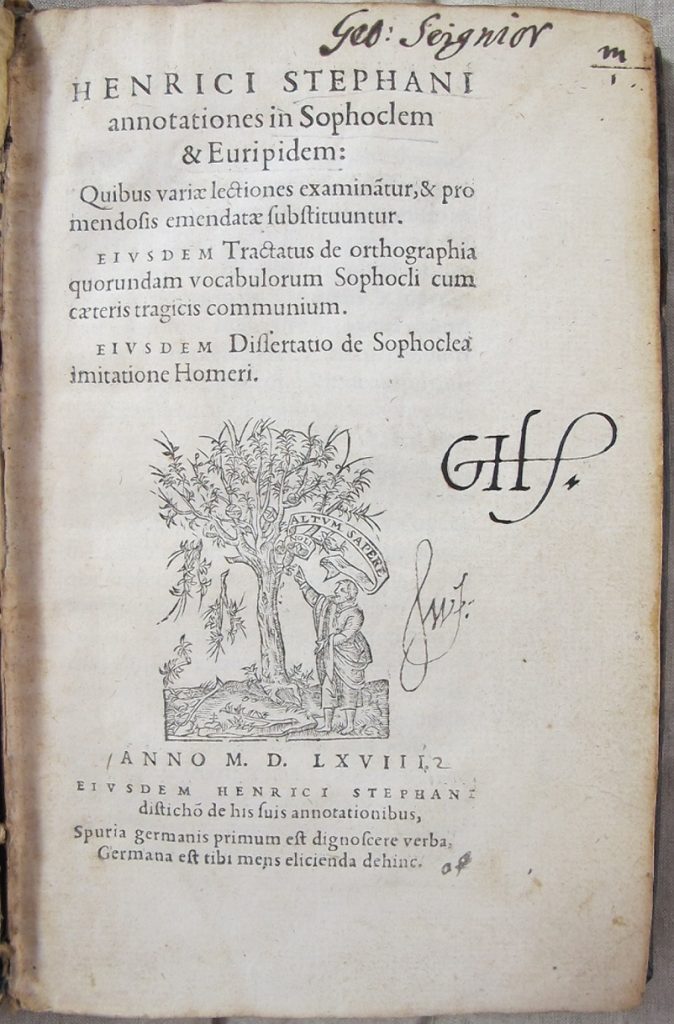

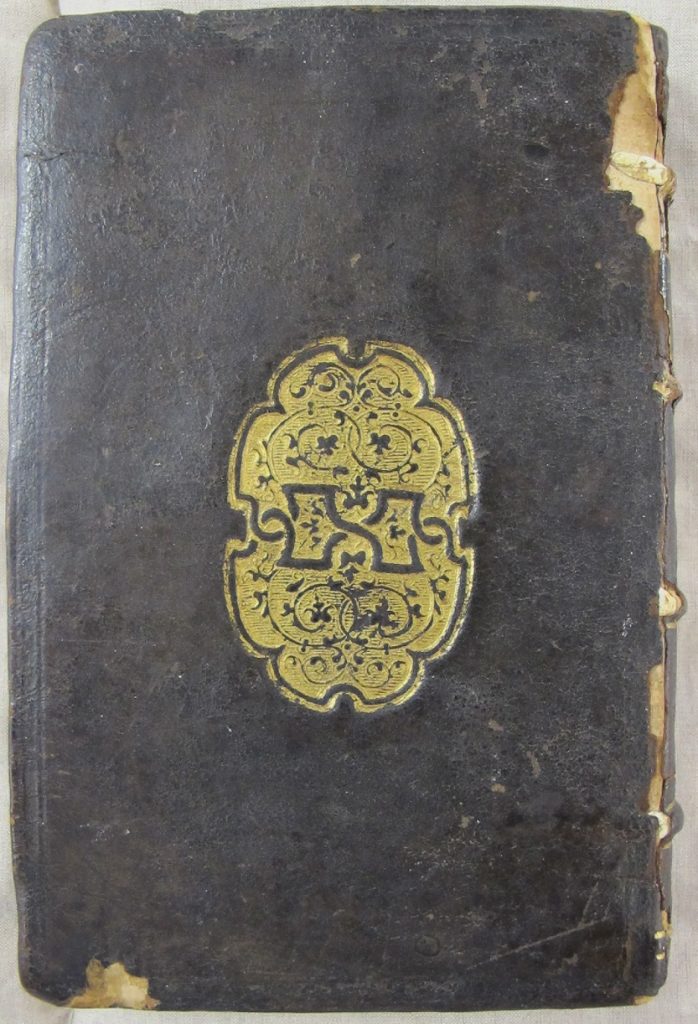

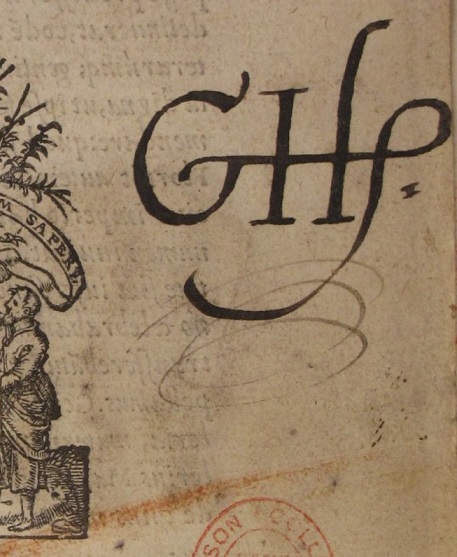

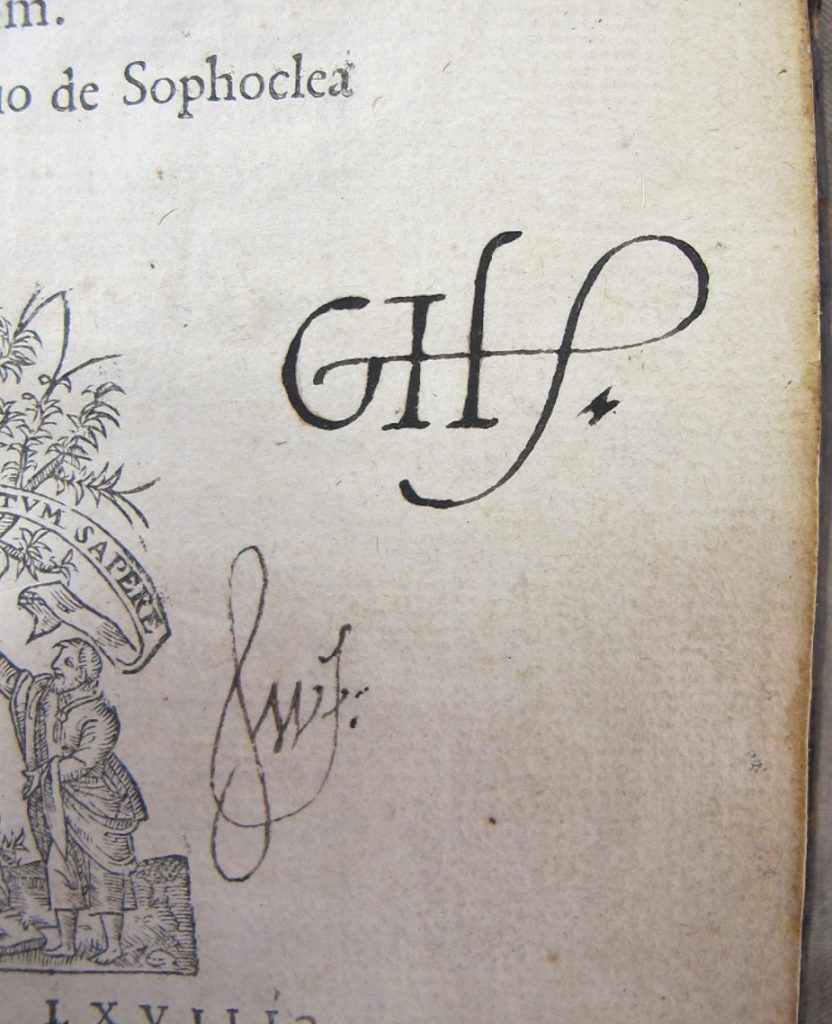

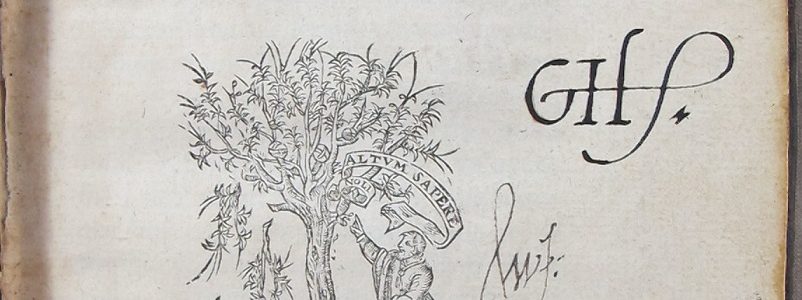

Our recent acquisition (now catalogued as Adv.d.8.2) is a copy of Henri Estienne’s Annotationes in Sophoclem & Euripidem (Geneva, 1568). It seems to be in a Cambridge binding of the 1570s (the gilt tool is similar to those seen on other books of the period now in the Library and can be found as fig. 3.37 in David Pearson’s English Bookbinding Styles, 1450-1800) and crucially bears Harvey’s initials (GH) boldly on the title page (see below right). It was this image in the bookseller’s description (not described as Harvey’s but instead linked to the George Seignior whose name appears above) which jumped off the screen at me and comparison with another of Harvey’s books on our shelves (a copy of Valerius Maximus: Paris, 1544/5) confirmed it matches exactly. This title is not in any lists of books known to have belonged to Harvey, but he did have another of Estienne’s books (L’introduction au traité de la conformité, Geneva 1566). One of Harvey’s books in the University Library (a 1575 London-printed life of Catherine de Medici, acquired in 2019 with the help of the Friends of the National Libraries), though anonymous, is thought also to have been written by Estienne. Harvey’s copy of Euripides’ Hecuba, & Iphigenia in Aulide (Venice, 1507) is now at Harvard. The annotation just below Harvey’s GH (below right) has not been identified and anyone with ideas is welcome to contact us.

Even though it sadly bears none of Harvey’s characteristic annotations, a previously unknown volume from his shelves remains an exciting discovery. It is, though, possible to piece together something of the volume’s later history. At the head of the title page is the name Geo: Seignior is a seventeenth-century hand. This seems likely to be the George Senior/Seignior who entered Trinity College (having come from Westminster School) at Easter 1659. There he would presumably have come across the young Isaac Newton, a student at the college between 1661 and 1665 before becoming a fellow in 1667. Although he died young (assuming he was in his late teens in 1659 he would only have been in his late forties at his death in 1678) he rose to some prominence, becoming a fellow of Trinity in 1664, serving as chaplain to the Bishop of Derry and Earl of Burlington, and as vicar of St Michael’s (that is, Michaelhouse, formerly a chapel used by Trinity College) in Cambridge. Seignior donated part of his collection of books to his college in 1676, but it seems likely that Harvey’s copy of Estienne was still kicking around the second-hand bookshops of Cambridge some thirty years after his death, where is was picked up by Seignior.

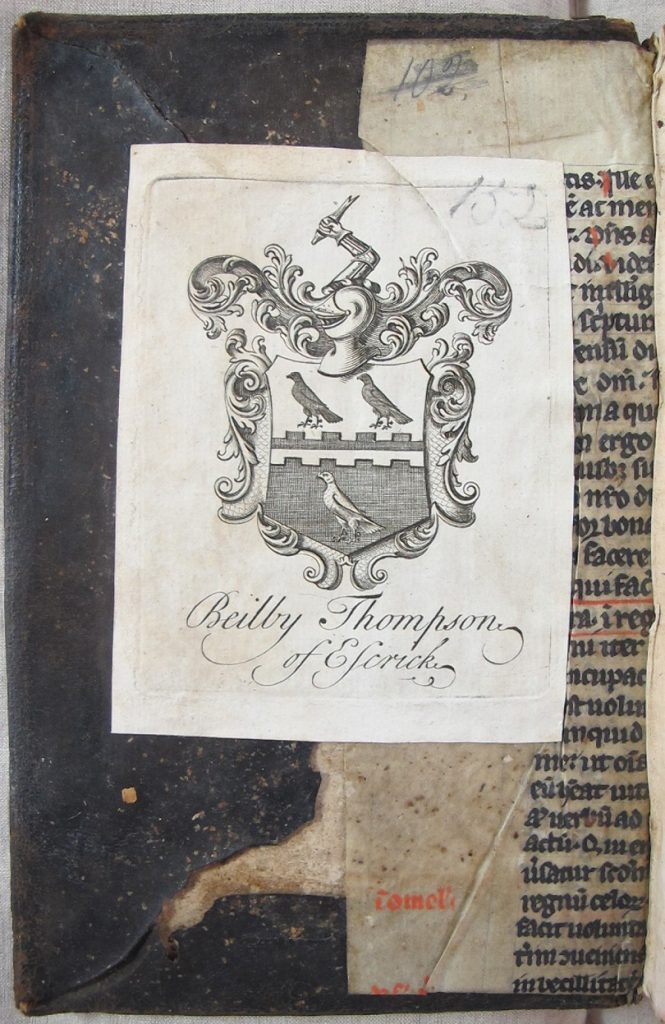

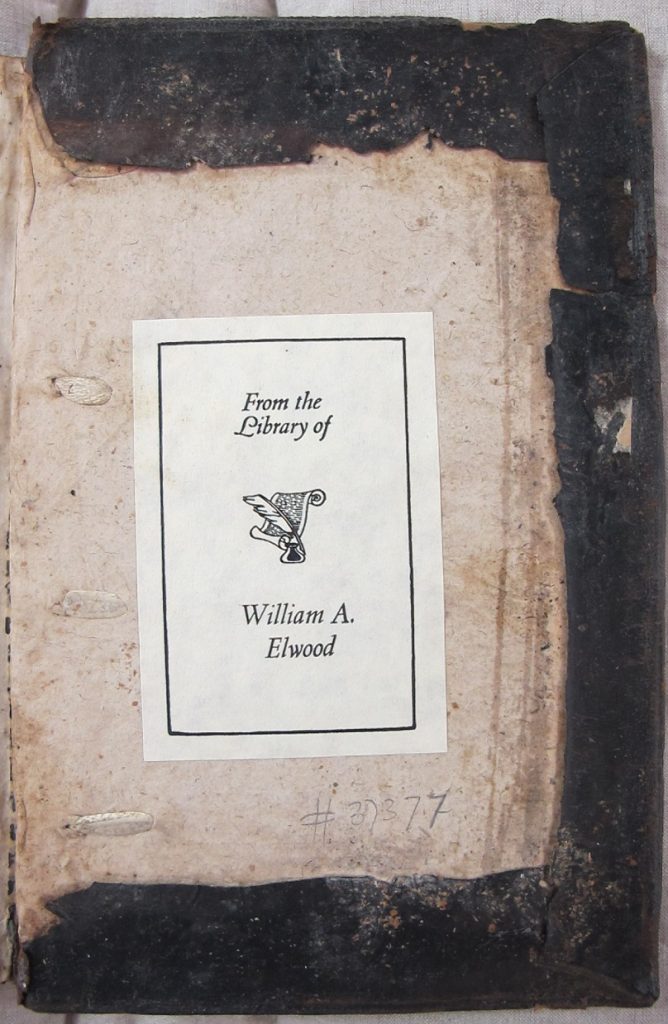

The only other early provenance relates to Beilby Thompson of Escrick in Yorkshire (1742-99), whose bookplate can be found on the front pastedown. Having inherited the family estate at the age of seven or eight, Thompson went on to study at Cambridge, entering Christ’s College exactly a century after Seignior arrived at Trinity, in November 1759. He was a fellow commoner (an affluent, usually aristocratic, student granted among other privileges that of sharing with the Fellows of a College the amenities of the high table) and seems – as was frequently the case for such students – not to have graduated. He served as a Yorkshire MP for nearly thirty years and was evidently a keen collector of books. Thirty of his books are recorded in the ESTC database of pre-1801 English imprints and hundreds of others probably lie unnoticed on library shelves. Harvey’s book may have remained in Cambridge following Seignior’s death, to be picked up there by Thompson, or he may have acquired it elsewhere. In the twentieth century the book was acquired by one William A. Ellwood (bookplate to read pastedown), presumably the Professor of English at the University of Virginia.

The return to Cambridge of another of Harvey’s books (especially one whose link with Harvey has only just been made) is a happy day for us and we hope scholars will enjoy consulting it in the months and years to come.