James Rendel Harris: a Bible scholar on a quest for manuscripts

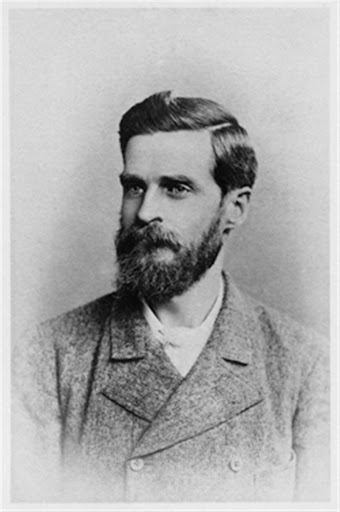

The later decades of the nineteenth century witnessed new directions being forged in the study of biblical texts, as new manuscript discoveries stimulated advances in scholarship. In Cambridge, the leaders in the field included the Anglican scholars J. B. Lightfoot, Brooke Westcott and F. J. A. Hort, and it was in 1881 that Westcott and Hort published their remarkable translation of the New Testament from the Greek. This was also a notable era for manuscript acquisitions when, in 1897, the Taylor-Schechter Genizah collection of manuscript fragments was brought from Cairo to Cambridge by Solomon Schechter. A less well-known figure but from this same era, was the scholar and collector James Rendel Harris, a specialist in early Christian texts and palaeography. He studied and taught in Cambridge for parts of his long working life and on the many expeditions he made to the Middle East he became an avid collector of manuscripts, with a focus on religious texts.

Rendel (as he is usually known), came from a modest background, born in Plymouth in 1852, into a large family where he was brought up as a Congregationalist. From the local grammar school, he gained a place to read mathematics at Clare College in Cambridge. Here he met other nonconformist students and was influenced by the evangelical Christian movements sweeping the country in the 1870’s. He began to attend the local Quaker meetings held in Jesus Lane and the faith formed here sustained and supported him throughout the remainder of his life. His belief was also strengthened by his marriage, in 1880, to another Quaker, Helen Balkwill, also from Plymouth.

After graduation in 1875, Rendel became a tutor in mathematics at Clare, but during his undergraduate years he had also begun textual studies with Hort, under whose influence his interests developed in new directions. The recent Greek translation of the New Testament inspired Rendel to concentrate on similar studies, relying on his knowledge of classical languages dating back to his school days. At Clare, he became the college librarian, spending time organising and cataloguing the library contents, and it was here that he began to read manuscripts with enthusiasm and increasing skill. In 1882, he published New Testament autographs, the first of his many publications and later in the same year, he was offered a post in New Testament Greek by Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. While on study leave in from his post in 1884, Rendel carried out a survey of manuscript sources in Cambridge, London and in European libraries and he began to fully realise the significance of original manuscript sources for new research. This idea became the impetus behind his own expeditions to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East which he carried out over a period of thirty-five years.

Rendel left John Hopkins in 1885 and returned to Cambridge where, in the same year, he was officially accepted into the Quaker community. This took place at a meeting held in Wisbech where Rendel had befriended another Quaker, Alexander Peckover (Lord Peckover, 1830-1919), the local banker and philanthropist. He was also a manuscript collector and remained a friend and fellow collector throughout Rendel’s life. The following year, as no post was available for him in Cambridge, Rendel accepted a post at Haverford College, an American Quaker University near Philadelphia, where he added to his language skills by learning Syriac.

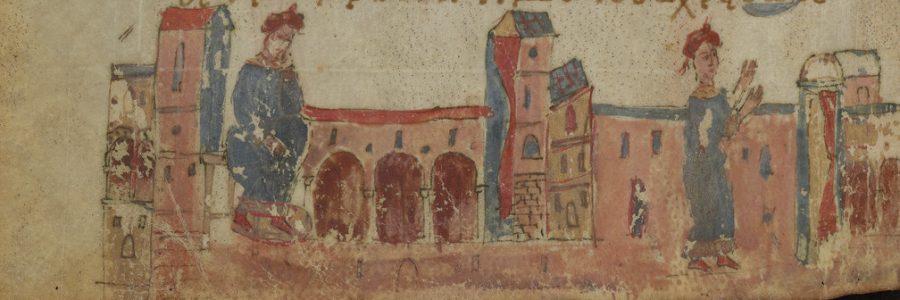

At both Johns Hopkins and Haverford, Rendel missed the wealth of the library collections formerly available to him in Cambridge. Taking leave of absence in 1888-89, he made his first visit to the Middle East, visiting Palestine and Egypt in search of manuscripts and acquired texts in Hebrew, Arabic, Syriac and Ethiopic, some of which he donated to Haverford College. He also made his first visit to St Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai with the American archaeologist Frederick Bliss, and where he became firm friends with the Monastery’s librarian, Galaktéon. It was here, following in the footsteps of the Cambridge Arabic professor E. H. Palmer, who had visited only a few years previously, he discovered the Syriac version of the Apology of Aristides (previously known only from the Greek version) on which he published in 1891. Almost simultaneously, this text was found to be included as part of the text of Life of Barlaam and Joasaph, a seventeenth century copy of which is held in the library of Pembroke College Cambridge (Pembroke MS 291). This was the copy Rendel used, with his colleague J. Armitage Robinson, to publish another edition on this text in the same year.

Westminster College. Sisters of Sinai Travel Lantern Slides (WGL4/6-286)

In Cambridge, Rendel’s studies on the early history of the New Testament text had focused work on the fifth century Greek and Latin manuscript, the Codex Bezae (Ms Nn.2.41), written in a tradition which Rendel considered to be a more original reading than those researched by Hort and the other Cambridge biblical scholars. He published his work on the Codex Bezae in 1891 while in America, and though his work has now been superseded by more recent scholarship, he made a significant contribution to the study of this text.

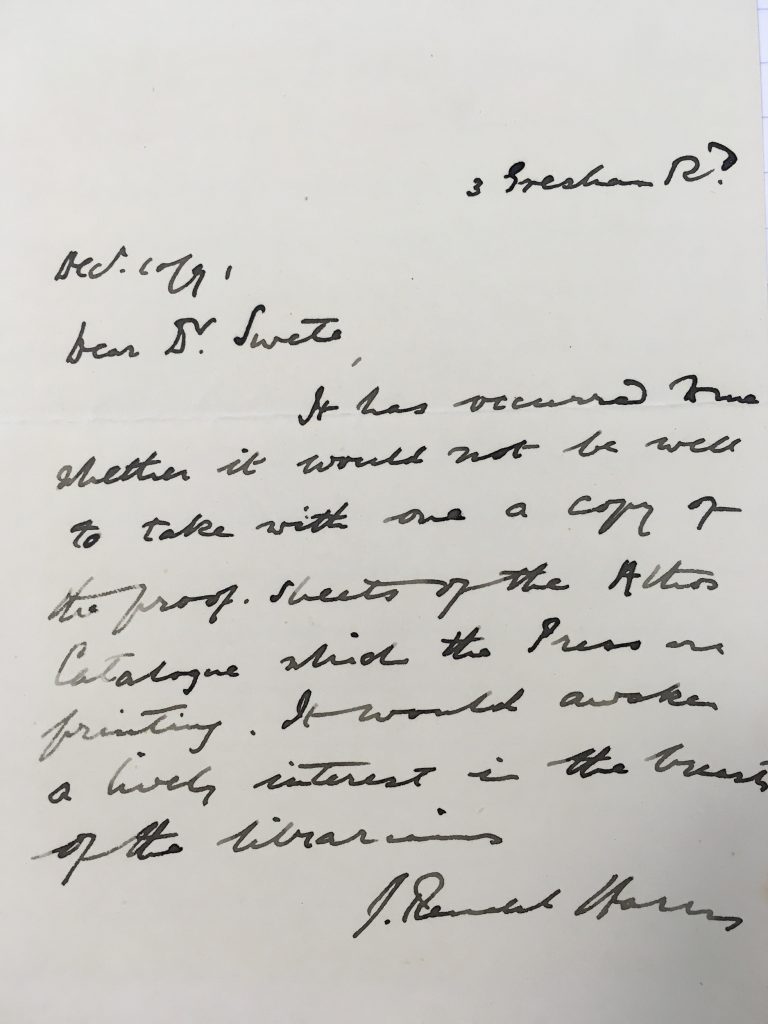

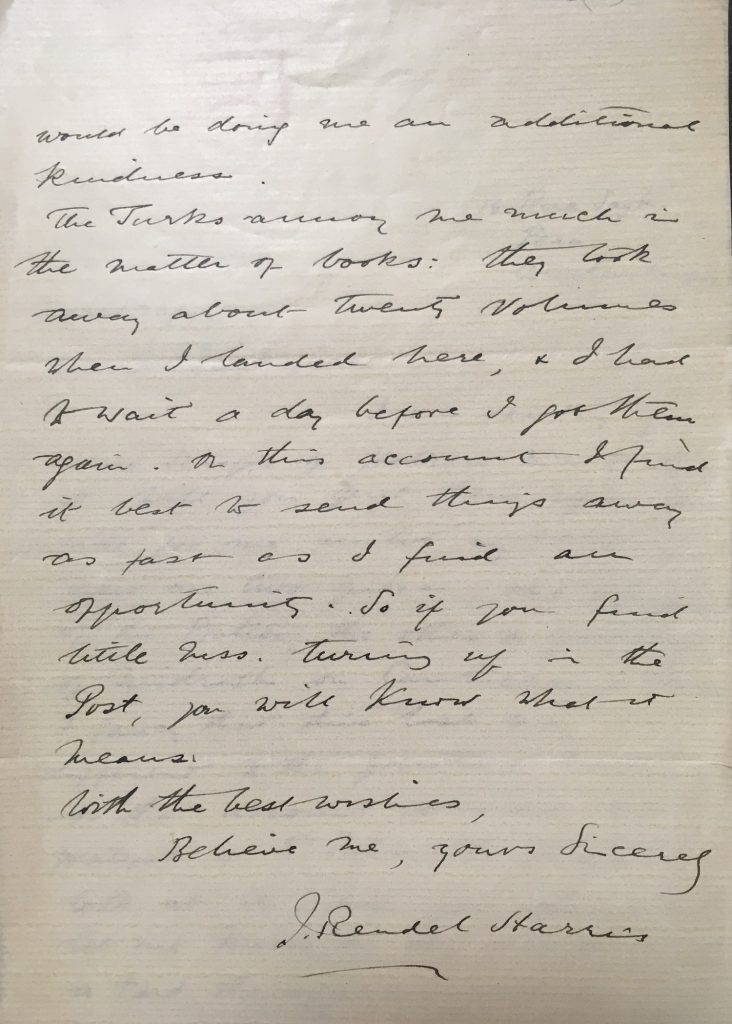

In 1892, after the success of his mission four years previously, Rendel made a second expedition to search for manuscripts visiting Jerusalem, the nearby Monastery of Mar Saba, also parts of Turkey and Greece. In a contemporary letter to Francis Jenkinson, the University Librarian in Cambridge, Rendel discusses his acquisitions and requests advice on fragments of a Hebrew text , a matter which Jenkinson referred to Solomon Schechter. The second page of the letter describes some practical problems relating to his acquisitions which Rendel encountered with Turkish officials who at this time were becoming increasingly conscious and critical of the removal of artefacts and books by collectors and subsequently exported.

In 1892, and on the strength of his scholarship and in recognition of his extensive manuscript expertise, Rendel returned from America to Cambridge to a lectureship in palaeography specially established for him, and to a fellowship at Clare College. In Cambridge he became firm friends with the twin sisters Agnes Lewis and Margaret Gibson, who attended his classes in palaeography. The sisters were also students of early Christian texts and it was Rendel who was the first to tell them about the treasures of St Catherine’s Monastery, mentioning the ‘dark closet’ full of manuscripts which they subsequently explored. On their first visit to St Catherine’s in 1892, it was from Rendel that the sisters took a letter of introduction to the monks there. He had also instructed them in the use of a camera which they used to photograph the texts they subsequently discovered.

Westminster College. Sisters of Sinai Travel Lantern Slides (WGL4/6-276)

In 1893, Rendel joined the sisters on their expedition to St Catherine’s along with Professors Robert Bensly, Francis Burkitt both with their wives. In a sense he was the odd man out in the party, but he was a staunch supporter of the sisters in their work. Rendel took his part in the long process of transcribing the manuscript text of the Codex Sinaiticus Syriacus palimpsest which the sisters had discovered there. He also helped to dispel the acrimonious disputes which broke out in the party both during the time at the Monastery and after the publication of their findings.

Rendel’s time at Cambridge came to an end in 1903 when he decided to accept a post offered to him as the first Director of Studies at the newly established Quaker college at Woodbrooke in Selly Oak, Birmingham. Founded by the Quakers and chocolate manufacturers John Rowntree and George Cadbury, he accepted this in preference to the professorship of early Christian literature at the University of Leiden which was offered to him in the same year. Rendel had, over the years, become a leader in the liberal Quaker movement and judged that at Woodbrooke, he could successfully follow both his religious and academic paths in parallel.

As a development stemming from their religious commitments, Rendel and his wife had also become deeply involved in humanitarian work in support of the cause of the Armenian population who were survivors from the massacres carried out by the Ottomans in the late nineteenth century. They travelled to Armenia and carried out relief work there in 1896 and again in 1903, and more manuscripts were also acquired on these expeditions. In response to any queries made about his collecting methods, Rendel always claimed that all his manuscripts were bought quite legitimately from the manuscript dealers he met, some of whom became his long-term friends. He also commented that this often proved to be a very long-winded process.

It was through such a contact that Rendel met Alphonse Mingana (1878-1937), an Iraqi scholar with a wide range of language skills including Syriac and Arabic, whom Rendel persuaded to join him at the Woodbrooke community in 1913. Mingana was also a skilled manuscript collector and under Rendel’s patronage, amassed an outstanding collection of manuscripts now housed in at the University of Birmingham. Mingana also collaborated with Agnes and Margaret in research on a Syriac palimpsest manuscript they had bought in Cairo in 1895 and which they later donated to the Library in Cambridge (CUL MS Or.1287). This manuscript is included in the Library’s Ghost Words exhibition.

Despite his move to Woodbrooke, away from the manuscript collections in Cambridge which he so valued, Rendel’s interests as a collector did not waver, nor were his expeditions without incident. On two occasions during the WW1, in 1916 and in 1917, Rendel only narrowly escaped disaster at sea. Intending to sail to India to visit a colleague, Rendel’s ship was torpedoed in the Mediterranean but he was fortunately rescued and landed in Alexandria. On the return journey in the following year, and after several days at sea he was rescued from a similar attack and landed in Corsica. Between these two disasters he had visited Egypt and collected manuscripts in Cairo, Asyut, Fayyum and Oxyrhynchus. Fortunately, these had been stored in Egypt, escaping the near fatal voyage back home and were added to the John Rylands Library collection in Manchester in 1917.

Rendel left Woodbrooke in 1918 and moved to Manchester where he was appointed curator of eastern manuscripts at the John Rylands Library and where he remained at work until his retirement in 1925. He made one final trip to Sinai in 1922-23 but failed to discover the text he had hope to find there and never ventured abroad again. He retired to Selly Oak in Birmingham, where a library was founded in his name and where he lived until his death in 1941. The Rendel Harris Library originally formed part of the Selly Oak Colleges libraries but is now part of the University of Birmingham Library’s Special Collections. Later in life Rendel decided, with some sadness, to dispose of some of his manuscripts to other collections. Some of his Syriac manuscripts he sold to Harvard University, others to the John Rylands Library. A valuable Peshitta manuscript he gave to his friend Alexander Peckover and others he donated include Syriac volumes to the University of Leiden.

Rendel Harris was a scholar with a distinguished reputation as a teacher and with an extensive list of publications, which later in life focused on theology and folklore, rather than on manuscript texts. Perhaps he was influenced in this by his friendship with Sir James Frazer whom he had known in Cambridge. Also during his time in Cambridge Rendel was deeply involved in the production not only of his own publications but in those of others. A considerable collection of his correspondence survives, providing an invaluable window into his life and work, in several Cambridge archives such as the University Library (including in the archive of the University Press) and in Girton, Westminster and Churchill Colleges.

CUL, University Archives, UA/Pr.B.13.G.47

It was during his ten years in Cambridge, in the final decade of the nineteenth century and the first years of the twentieth, that Rendel was a consistent presence and support there to many others in his area of expertise. His interest in manuscripts, dating back to his time as librarian at Clare College, and which subsequently developed into a lifelong passion, is sometimes overlooked in contrast to his academic and spiritual interests, yet his manuscript endeavours provide a constant thread weaving in and out of the narrative of an adventurous life.

References

Coakley, J. F. A catalogue of the Syriac manuscripts in Cambridge University Library and College libraries acquired since 1910. Ely: The Jericho Press, 2018.

Falcetta, Alessandro. The Daily Discoveries of a Bible Scholar and Manuscript Hunter: A biography of James Rendel Harris 1852—1941. London: T & T Clark, 2018.

Falcetta, Alessandro (2004). “James Rendel Harris: A Life on the Quest”. Quaker Studies, 8/2: 208–225.

Harris, J. Rendel and Harris, Helen, The newly recovered apology of Aristides, its doctrine and ethics: with extracts from the translation. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1891.

Harris, J. Rendel. Codex Bezae: a study of the so-called western text of the New Testament. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1891.

Pickard, Irene. Memories of J. Rendel Harris. Birmingham: Woodbrooke College, 1978.

Soskice, Janet. Sisters of Sinai: How Two Lady Adventurers Found the Hidden Gospels. London: Vintage, 2010.

Vandrei, Martha. Harris, James Rendel (1852–1941). ODNB https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/33726 Last accessed 4 October 2021

I have been enjoying deeply The Odes of Solomon

Rediscovered by Rendel Harris in 1908.

I would love to write a creative book reflecting on

The deepening of spiritual faith that The Odes can inspire

And the Biblical Scholarship Harris contributed to in his life and the tradition that continues today. I am currently a member of the Minnesota Christian Writers Guild and the Minnesota Association of Christian Songwriters

which is why I love the Odes so much.

Thank you for your comments – I am glad you enjoyed the blog

Hi.

My question is not about the blog but about the MSS that Harris sold to Harvard library. As far as I know and it was confirmed in this blog, that Harris didn’t travel to the city of Mosul which was part of the Ottoman Empire at that time. However, most if not all the MSS he sold to Harvard in 1905, originated in Mosul and they were scribed by a person called Mattai Bar Paulus, a deacon in the Syriac Orthodox church in Mosul and probably the most prolific scribe in the history of Syriac MSS. Is there any idea how Harris acquired these MSS? Later, Harris and Alphonse Mingana after 1910, acquired more MSS from MBP but I’m really interested in how he aquired the MSS before 1905.

Naseer AbdulNour

I enjoyed this article very much! I just read the book, The Sisters of Sinai, where J.R. Harris was portrayed. This led me to looking up more about this fascinating man and your interesting article! I’d like to find and read a biography on him.