Archives in the round: joining up the records of Biochemistry

Puzzling over an unidentified collection of 1920s printer’s blocks, intriguing artwork for something, has emphasised again the connections between the official records of the University and personal papers of its scientists. For the fullest picture of an institution or an individual, look both ways.

The blocks, part of transfer of administrative records from the Biochemistry Department just before the first Lockdown, and now catalogued online, turn out to be illustrations for Brighter Biochemistry, the Biochemical Laboratory’s inspired comic magazine. Its many contributors, otherwise engaged in serious research as established academics, graduate students and support staff, satirized discoveries in the relatively new field of biochemistry, and each other. Across eight issues, 1923-31, the publication contributed towards building a community outside the gendered confines of the Colleges and among staff and students at all levels.

Among the participants:

- Frederick Gowland Hopkins (1861-1947), first Professor of Biochemistry, dynamic and much-admired Head of Department, familiarly known as Hoppy, penned ‘A truncated saga’ of his 1929 journey to Stockholm to receive a Nobel prize for the discovery of vitamins (issue 7, January 1930, pp.6-8). The magazine’s first issue had included analysis of a papyrus fragment, the Book of Hoppi, detailing the worship of the semi-divine Het-Rekh, Egyptian sage (issue 1, December 1923, pp.36-8); this only a year after Howard Carter’s discovery of the tomb of Tutankamun. Hopkins’ personal papers are at the University Library.

- Malcolm Dixon (1899-1985), whose research focused on enzymes, contributed limericks and spoof experiments. Dixon’s personal papers are at the University Library.

- Robin Hill (1899-1991), at that point studying cytochromes, deployed a fisheye (or celestial) camera of his own design to photograph the new laboratory buildings, the Sir William Dunn Institute, through 180 degrees. ‘So many biochemists have looked round our department that it is time it looked round itself’ declared the magazine (issue 4, February 1927, p.27). Hill’s personal papers are at the University Library, including a quantity of slides, taken with said invention, featuring Ely cathedral in stereoscope.

- Dorothy Needham (1896-1987), pioneering researcher in muscle biochemistry, wrote poems, short stories and letters to the editor, signed ‘Temeraria Boulderdash’, (issue 5, December 1927, p.54). D. Needham’s personal papers are at Girton College.

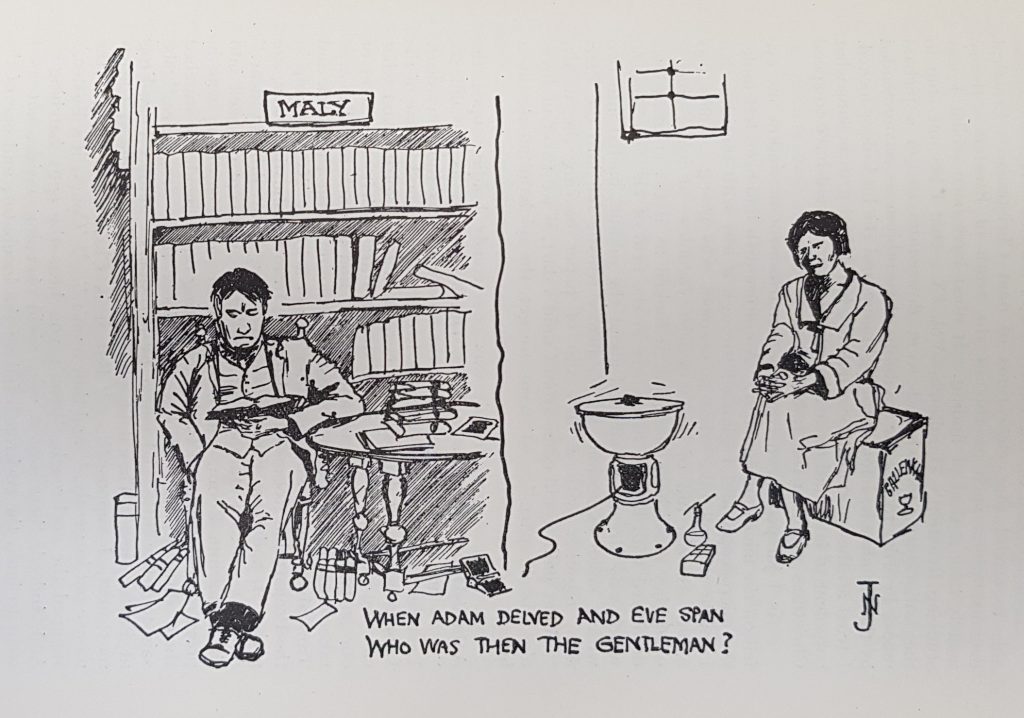

- Joseph Needham (1900-1995), subsequently author and inspiration for the multi-volume work Science and Civilisation in China (1954-ongoing), among many other achievements, drew cartoons. J. Needham’s personal papers are at the University Library and Needham Research Institute.

- Margory Stephenson (1885-1948), microbial specialist and the first woman biological scientist to be elected to the Royal Society, celebrated her bacteria in ‘Down the microscope and what Alice found there’ (issue 5, 1927-8, pp.36-9). Stephenson’s personal papers are at Newnham College.

- Margaret Whetham (1900-1997), working on bacterial metabolism with Stephenson, and an early editor of the magazine, contributed to a series of ‘Cautionary Tales for Biochemists’, including ‘Belinda who broke everything and left the laboratory under lamentable circumstances’ (issue 4, February 1927 pp.31-2).

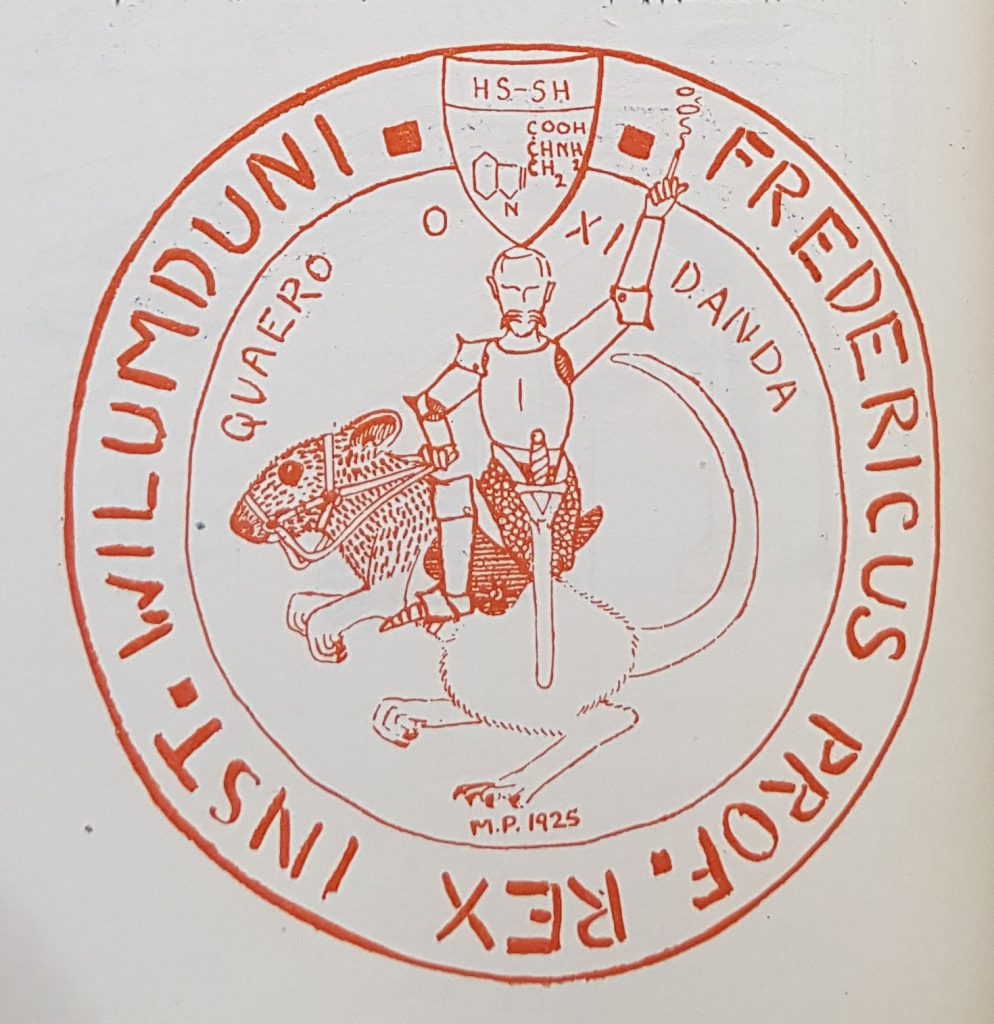

A recent post by Sally Kent emphasised the centrality to Biochemical research of laboratory animals and enduring oversight of technician Ruby Leader. The artwork for a piebald rat was among the blocks and is reproduced at the top of this post. Drawn by graduate student Michael Perkins (Trinity College, PhD 1929) in a heraldic manner in imitation of the Wembley Lion, emblem of the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley in 1924, it was dubbed the William Dunn Lion. Elsie Watchorn (Newnham College, PhD 1929), researcher in nutrition for the MRC, is shown holding such a rat in a wonderful photograph album, digitised by the department. She had the later distinction of being one of the first women to hold a University position as Demonstrator, 1946-53.

Hopkins was a keen supporter of women in science. His opinion clearly conflicted with that of the writer of Chemistry and Industry in 1924 who observed that ‘It [the new institute] is probably too much the resort of women students, who cannot be expected to bring to the study of the subject that breadth and originality of outlook and the acute powers of observation that are essential to progress.’ Among the comparatively numerous women in the laboratory was Sylva Thurlow (Newham College), graduate student of Malcolm Dixon, working on oxidations. She was the first woman to obtain a Cambridge PhD in a science subject in 1924. Despite these positive steps, the journal couldn’t but reflect broader social attitudes and institutional hurdles to equality: in Joseph Needham’s cartoon (below), for instance, showing the division of labour (issue 3, Dec. 1925, p.23), or a poem about an escaped rat entitled ‘Plain Jane’ (issue 7, January 1930, p.45), or the sketch of an impoverished ‘biofemina’ modelling a flapper dress cut from a Henry Tate sugar sack (issue 5, December 1927, p.26).

The broader body of departmental records transferred in February 2020 includes teaching and library materials. Practical worksheets for student lab classes survive from 1930 onwards, including sessions on enzymes and bacteria, adjuncts to lectures for Part II of the Natural Sciences Tripos given by Malcolm Dixon and Marjory Stephenson. Dixon’s personal papers include syllabuses, lecture lists and programmes of work. A rare survivor alongside, the notes of student Hugh K. King (Pembroke College, BA 1938), taken at those very lectures, show how novel ideas were being received by the young and inexperienced; how research fertilizes teaching. In his reminiscences of the early years of the Institute, Dixon noted the complete absence of ready-made biochemicals. Everything had to be concocted from scratch including essential amino-acids and coenzymes. The practical worksheets include ‘recipes’ for everything from the simple, blood products haemitin and native globin, to the more complicated, such as dimethyl pyrrole dimethyl carbolic ester.

Establishing Biochemistry in the inter-war period as a separate discipline concerned with the active chemistry of the life process, Cambridge biochemists made their own raw materials as they made their own fun.

Bibliography

‘Brightening Biochemistry: Humor, Identity, and Scientific Work at the Sir William Dunn Institute of Biochemistry’, 1923–1931 by Robin Wolff Scheffler in Isis: International Review Devoted to the History of Science and Its Cultural Influences, Vol.111, No 3 2020, pp.493-514