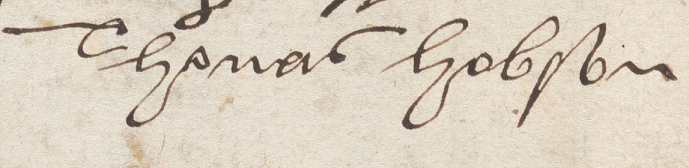

Long, long life and times of Cambridge carrier Thomas Hobson (1544-1631) now online

If you think only staff and students appear in the University Archives, think again. Episodes in the life of Thomas Hobson, recorded in University court and other records, are now online in the digital library thanks to research funding generously provided by Nigel Grimshaw (Queens’ 1971).

Biographical note by Nigel Grimshaw

Thomas Hobson is Cambridge’s most famous townsperson. Using sturdy wagons pulled by a large team of horses, he was a carrier of goods and people. He also hired out horses and thereby introduced the expression ‘Hobson’s Choice’ (‘this or none’) into the English language; it arose from his stipulation that a customer should ride only the most rested animal. Hands-on until he died aged 86, he became an institution and amassed immense wealth. Hobson was born around 1544 in Buntingford, a stopping-place 22 miles south of Cambridge on the road to London. His father, a carrier, had probably moved from Lincolnshire to expand his trade. The family re-located again in 1561 to Grantchester, just outside Cambridge. After Hobson inherited the carrier business in 1568, the family settled in Cambridge’s academic quarter at Ye Sign of the George on Trumpington Street. Acquired from Corpus Christi, the inn had barns, stables, garden and an orchard, approximately where St Catharine’s chapel is now situated.

Aged 33, he married Anne Humberstone. They were dedicated parishioners at St Bene’t’s, where their eight children were baptized. Hobson donated a King James Bible to the church, helping to secure for himself a revered resting place, without inscription, near the chancel. Thomas Fuller, man of letters (then aged 22), officiated at his funeral.

Tradition has graced Hobson with a reputation as a civic philanthropist. Yet his payment for a fountain in the market-place was curiously retrospective and his gift towards ‘Hobson’s Workhouse’ was likely linked to other matters. He provided generous maintenance for the fountain (also known as a conduit) but, over time, the entire ‘new river’ system became misleadingly known as ‘Hobson’s Conduit’.

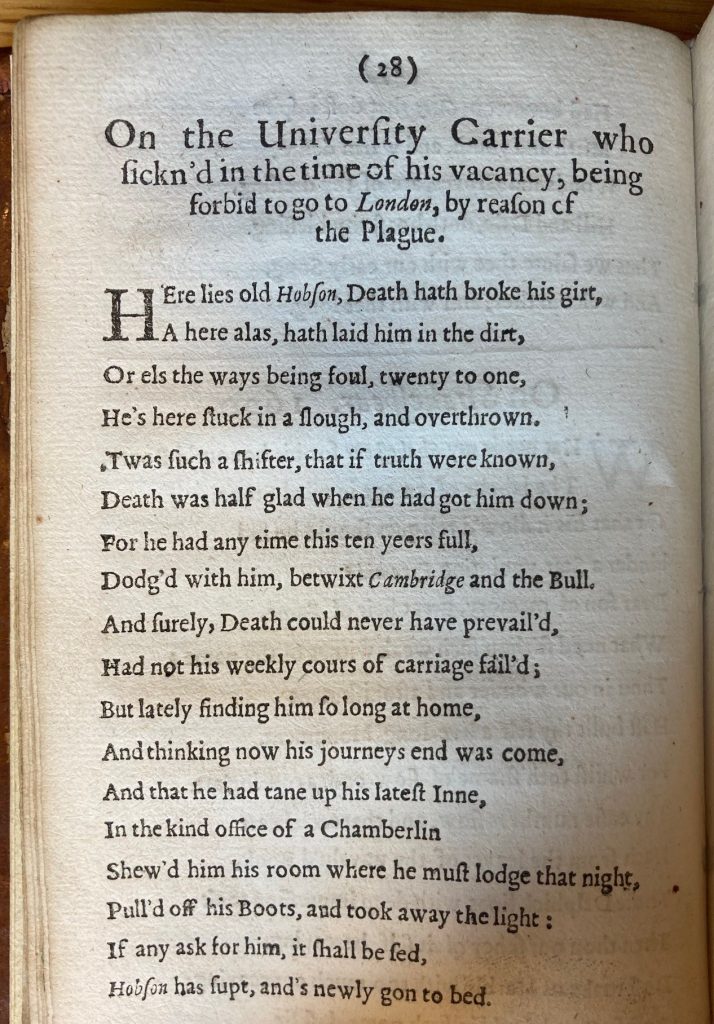

Hobson’s more evident aspiration was to use his resources to settle his successors, their spouses and families in fine manor houses, supported by rents and profits from estates attached with lordships of the manor. Three manors at Cottenham were bequeathed to his grandson Thomas, his main male beneficiary. Another grandson Charles was comfortably established in Chesterton. When his daughter Dorothy married Sir Symon Clarke, the carrier discharged the baronet’s heavy mortgages and ensured that the estates would accrue to her; an imposing portrait, dated 1620, of Hobson on a stately horse likely acclaimed her aristocratic elevation. His other surviving daughters were set up in the splendour of former monastic properties: Elizabeth at Anglesey Priory endowed with the manor of Anglesey-cum-Bottisham and Anne in Denny Abbey with the manors of Waterbeach and Denny. University records reveal Thomas Hobson, largely, as a measured operator. Economic expansion and wider access to education during this era assisted the emergence of an increasingly sophisticated urban merchant class. Hobson’s considerable accumulation of capital – derived from hard work, reliability and enterprise – was used to fashion privileged lives for his family as mid-ranking landed gentry. Hobson died in January 1631 during a period of inactivity caused by plague. In epitaphs, John Milton attested the University Carrier’s indefatigability: Here lieth one who did most truly prove, That he could never die when he could move.

Thomas Hobson’s appearances in Cambridge University Archives

Hobson features in the records as businessman, benefactor and bereaved father in the period 1587-1631. As such, his encounters with the University of Cambridge reflect its wide-ranging influence on local trade, welfare and public health; its importance in local social and economic history. They serve as a town-gown case study.

He was both plaintiff and defendant in the University courts, disputing with other tradesmen or the University authorities in cases relating to his business as carrier, as well as a side-line dealing in wheat, the extent of his property portfolio and the debts of his son, John.

He was first among the parishioners of St Bene’t’s donating towards almshouses and a House of Correction and supported a petition for poor relief. His haulage operation was subject to the orders issued to keep the town free of plague.

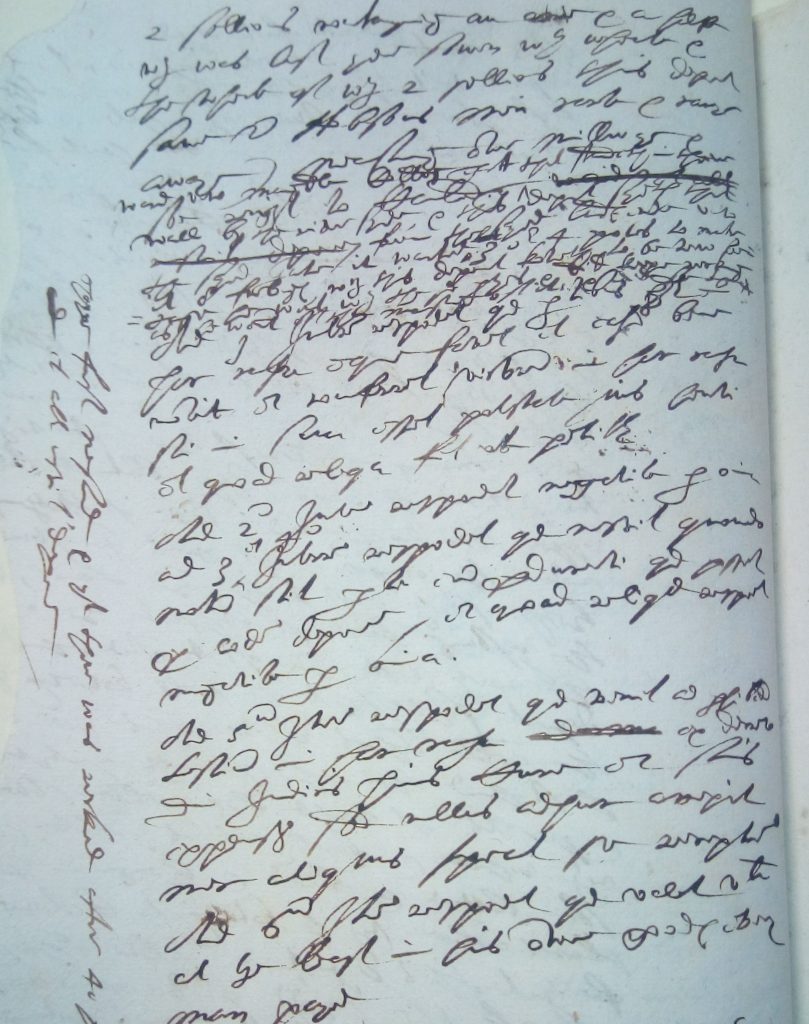

Case of John Rooke, disgruntled employee

By way of example, consider this colourful episode in the Vice-Chancellor’s Court. It began in July 1621 when John Rooke, servant now of one Master Sherman, sued Thomas Hobson for £7 in unpaid wages. In his defence, Hobson countered that some wages had in fact been paid over the period of two years and three months Rooke had been in his service and furthermore he had settled a London debt for which the servant was in danger of being arrested. But Rooke had not done a good job as a driver. Hobson listed much negligent behaviour for which he was financially liable, including drinking on duty and ruining horse teams by racing other carriers, culminating in the death under the wagon wheels of a young woman to whom he had given a lift, contrary to the rules.

Edward Sisseley, aged about 40, a longtime servant of Hobson, was summoned as a witness by Rooke. His statement in January 1621/2 however, seemed to confirm the views of his boss. Loyalty was rewarded. In Thomas Hobson’s will, Sisseley received the bequest of a messuage.

Thereafter, from February to July 1622, Rooke failed to appear in court, was pronounced ‘contumacious’ (legalese for stubbornly or wilfully disobedient) and ordered to be arrested on at least a dozen occasions.

Scope and arrangement of digitised records

The records of the University Courts run to 50 linear metres. For the two principal courts, those of the Vice-Chancellor and his Commissary, from the early sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth centuries, they comprise chronological series of Act and Deposition Books, bundles of evidence and other administrative records produced in court (known as exhibita) and probate material.

Close descriptive work on the Vice-Chancellor’s Court records has revealed many references to Thomas Hobson. Similar analysis is outstanding for the records of the Commissary’s Court. The digitised selection documents cases where Thomas Hobson is party to a suit or otherwise appears, for example as witness or creditor. His son, Thomas junior, features in one case. It also includes, from elsewhere in the archives, records relating to Hobson and poor relief, and Hobson and plague.

Digitisation has allowed records to be presented together for the first time, in thematic groups by court case or other appearance; i.e. by discrete ‘episode’. Archivists have also added several aids to interpretation and navigation:

- Each episode has an introductory summary and contents list

- All records are transcribed, except for entries in the courts’ Act Books and pro forma documents appointing lawyers or summoning defendants

- Latin abbreviations have been extended

- Spelling and punctuation have been transcribed as seen.

Nature and authority of the University courts

From successive monarchs the University accrued extensive juridical independence and authority in civil and ecclesiastical matters. By the reign of Elizabeth I, its courts were empowered to try cases affecting University members and other ‘privileged persons’ (that is, any townsperson providing a service to a University member) in the areas of felony, probate, licensing, debt, morality and discipline. In doing so, they competed with local borough and church courts.

The most important court, the Vice-Chancellor’s Court, dealt primarily with cases concerning senior members and in pursuit of its regulative authority. Probate was also processed here. The second, the Commissary’s Court, largely heard cases involving junior members and privileged persons. It sat in the University and, in special sessions commonly called ‘Pie-powder Courts’, at Midsummer and Sturbridge Fairs. The Proctors’ Leet heard cases concerning breaches of the peace, illegal gaming and offences against trade in victuals, licensing and weights and measures. In the Paving Leet, the University worked with the town authorities to agree sanitary measures, among them plague control. The two principal courts were at their most active in the period 1540-1660.

Other people and cases in the court records

Thomas Hobson was one among many locals using the University courts in pursuit of justice. Funding has also allowed the wide-range indexing of Court Act books during the period 1588-1631. Names, occupations, dates and case types are now part of the archival catalogue on ArchiveSearch.

Getting at this data, alongside similar information already online for depositions and exhibita, will facilitate use of the court records by family, legal and social historians. Interested in women and employment? See Mary Westfeild, tennis court keeper at Corpus Christi College, prosecuted in Sept. 1621 for making a door in the College’s brick wall, allowing scholars to exit and enter the College when the gate was shut. She was ordered to block the passage and brick up the wall. Student high-jinks? See Harrison, Crosland and James, scholars of Christ’s College, prosecuted in Feb. 1610 for shooting pigeons. They were suspended from their degrees and put in the stocks. Serial offenders? See Alice Holmes, widow and brewer, of Jesus Lane, prosecuted on at least 28 occasions between 1610 and 1630 for unlicenced victualling and for selling beer above the price set (see the five Act Books catalogued as UA VCCt.I.7-11).

The tangled, protracted saga of alleged book thief Margaret Cotton is currently preoccupying Dr Heather Woolf, the Library’s Munby Fellow in Bibliography. Her recent blog post attempts the unraveling of a dispute which began in the University Courts in 1602 and ended in Star Chamber in 1611.

The lives of 1000s of residents of Tudor and Stuart Cambridge are now a step closer to being known.