A unique treasure: Johann Wansleben’s Ethiopic notes and letters

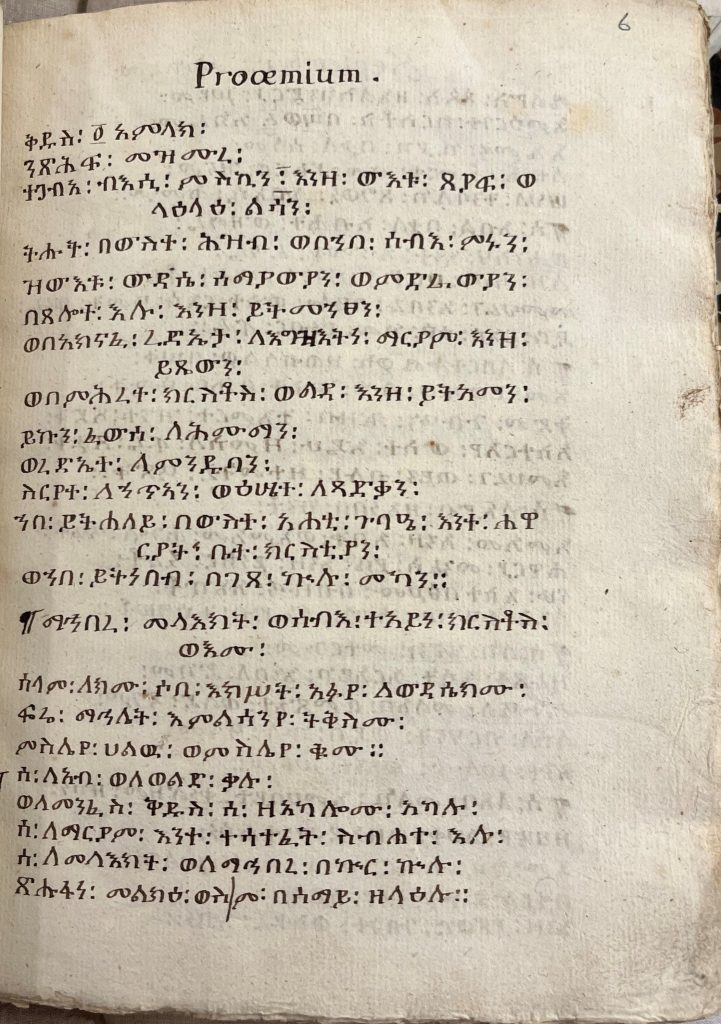

The manuscripts written in the Ethiopic language held in Cambridge University Library number fewer than seventy volumes in all, and for the most part, these came to the Library in the late nineteenth or early twentieth centuries from individuals with a diplomatic or scholarly background. One very modest manuscript originated from an entirely different source, not from Ethiopia at all, but is a notebook written by a German scholar of Ethiopic and acquired at least two centuries earlier. This manuscript (Ms Dd.11.38), though unremarkable to look at, contains notes made by Johann Michael Wansleben during a stay in England in 1661-2. It deserves a story all of its own.

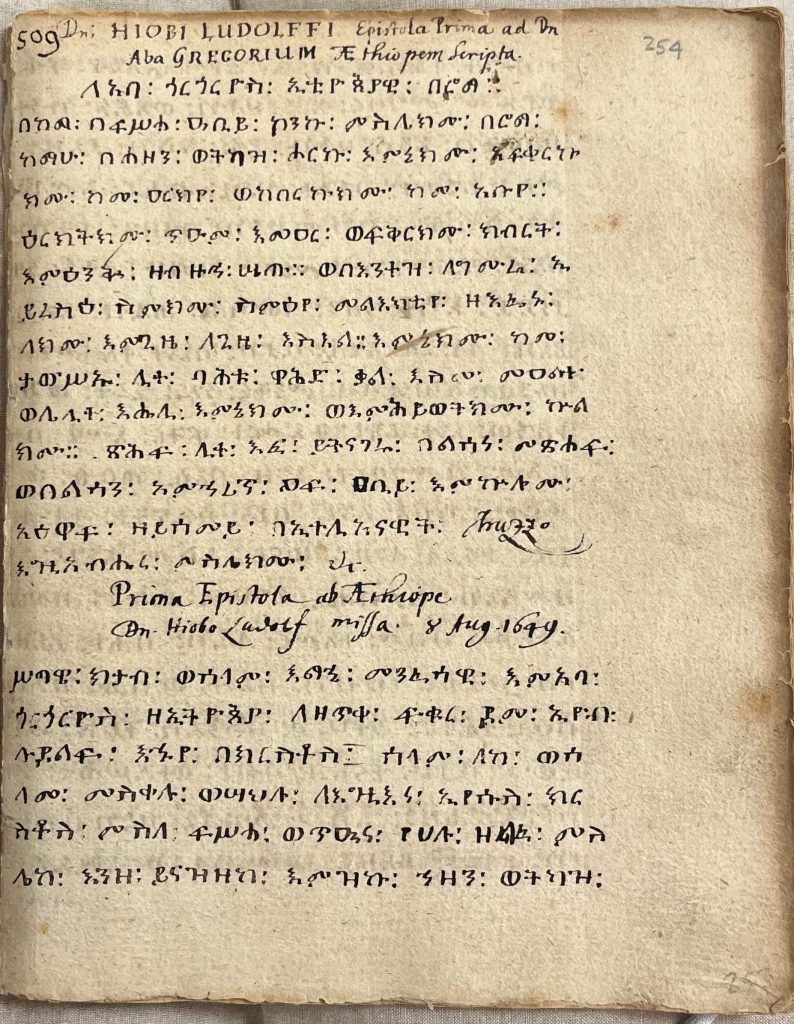

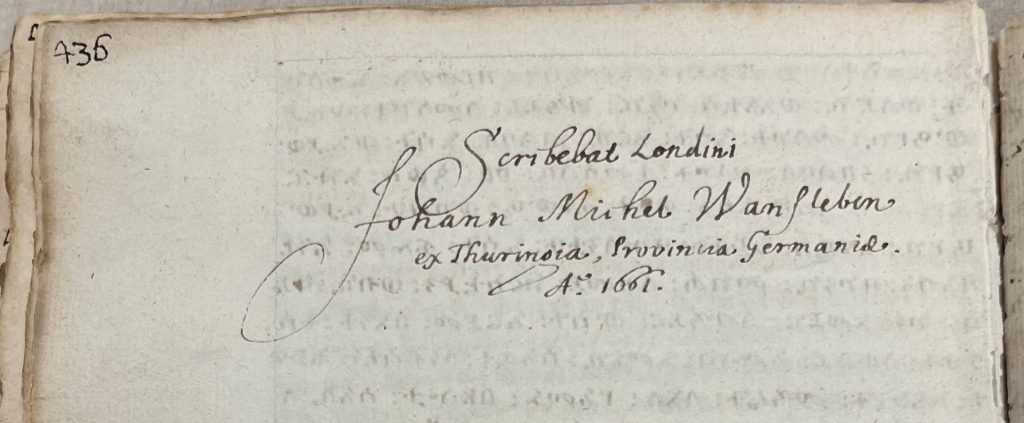

This manuscript consists of a small volume in a modern binding, accompanied by a separate sheaf of loose pages previously bound. It is written primarily in Ethiopic but with notes in Latin. One folio contains the author’s signature and the date 1661, indicating its authorship to Wansleben at a time spent working in London.

Wansleben (1635-79) was a proficient Ethiopic scholar, also a traveller whose interests focused on the culture of Ethiopia and its Christian Church. During his travels he extended his interests to include that of the Egyptian Coptic Church. The significance of the Ethiopic Church and its beliefs had been sparked among the German Lutherans from the late sixteenth century who thought that these teachings could be closer to original Christian teachings than to those of Roman Catholicism, and this might therefore throw new light on very early Christian beliefs and practices. It was also an aim of some European statesmen to forge trading links and diplomatic ties between Europe and Ethiopia against the Ottoman Empire.

Born near Erfurt in 1635, Wansleben showed an early interest in learning languages. It was at university that he first studied oriental languages and in 1656, due to a lack of other opportunities, he enlisted as a mercenary soldier in the Swedish army. In a diary written at this time, where he records texts and describes places he visited during his military service in Northern Europe, are the first indications of his fascination with the study of history and antiquities.

On his return to Erfurt, Wansleben met the eminent German scholar of Ethiopic, Hiob Ludolf, and became his student. Ludolf (1624-1704), also a native of Erfurt, had studied philology there and in Leiden. In 1649, while Rome researching archives, he had met an Ethiopian monk and scholar, Abba Gregoriyos, from whom he learned Ethiopic. The two formed a close bond and, in 1652, subsequent to cordial exchange of letters, Ludolf invited Abba Gorgoryos to Friedenstein Castle in Gotha where Ludolf worked in the service of Ernest I, the Duke of Saxe-Gotha. The two scholars collaborated on the earliest dictionaries and grammars in Ethiopic and subsequently Ludolf was to become the foremost scholar of the language in Europe.

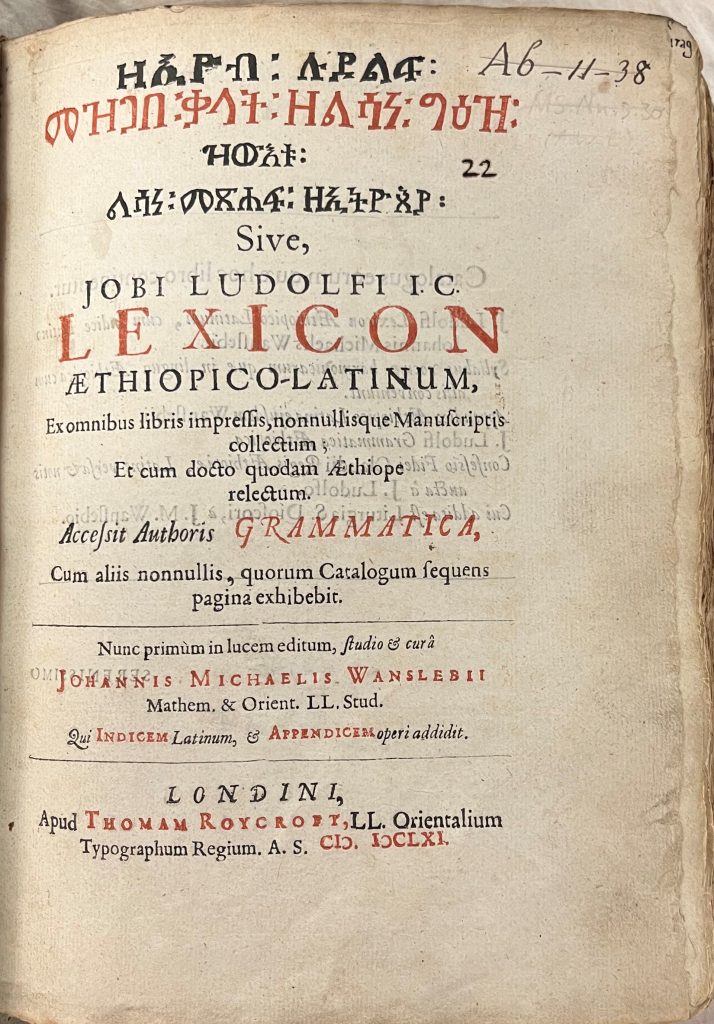

To return to Wansleben and his story, Ludolf was so impressed with his student’s progress in Ethiopic that in 1660 he sent him to London to assist with the preparation of his Lexicon Aethiopici-Latinum. Wansleben was to supervise the volume through to its publication the following year.

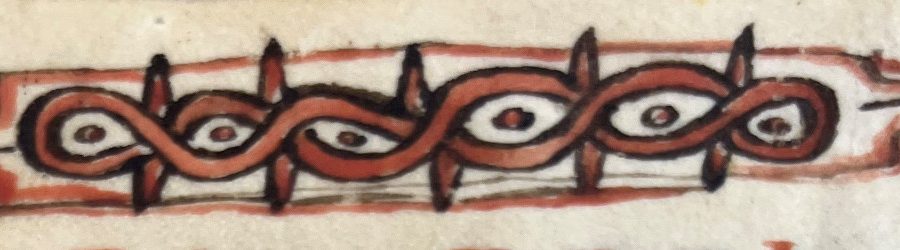

On completion of this project Wansleben stayed on in London to work with the Arabic scholar, Edmund Castell, on the publication of his Lexicon Heptaglotton and during this time he met other English scholars also working in this field of study, including Edward Pococke, the Oxford Professor of Arabic and manuscript collector. It was while in England, that Wansleben developed his expertise as a copyist, which included copying Ethiopic manuscript texts, a skill he continued to practise throughout his life.

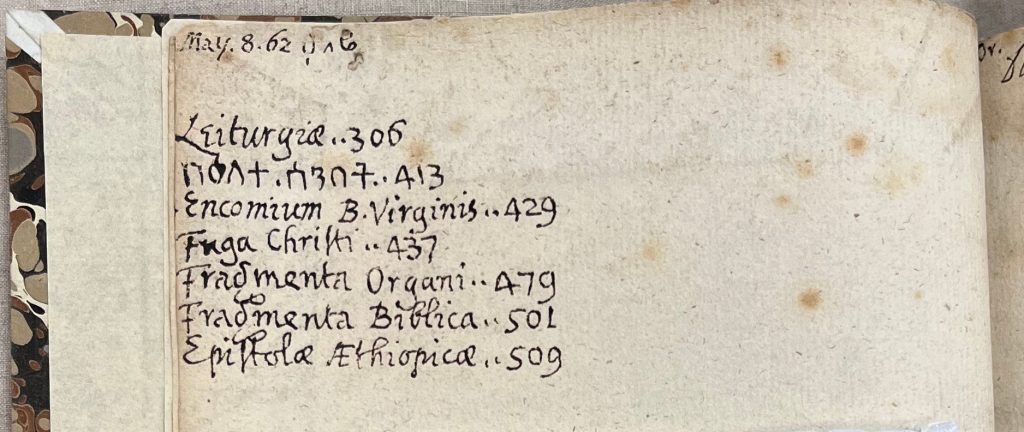

Edward Ullendorf, in his catalogue of the CUL’s Ethiopic manuscripts published in 1961, indicates that this manuscript by Wansleben contains several different texts. There are copies of Ethiopic manuscripts from the Bodleian Library’s collection acquired by Edward Pococke, during his time travels in the Levant. A second example of Wansleben’s signature in his manuscript volume notes Oxford in 1662 as the place of copying. These texts are described in detail by August Dillmann in his catalogue of the Oxford Ethiopic collections.

The second section of the manuscript, and compiled by Wansleben himself, is an alphabetical catalogue of more than 700 proper names which occur in the preceding texts, listed in Ethiopic and transcribed into Latin. In the third section of the manuscript are copies of some of the correspondence between Hiob Ludolf, and Abba Gorgoryos relating to the time between their two meetings in Rome and Gotha in 1649-52.

In 1663, after his return to Germany from London, Wansleben, still under Ludolf’s tutelage, found a patron in the person of the Duke of Saxe-Gotha, on whose behalf he planned to travel to Ethiopia with the aim of establishing religious and political connections there. Travelling through Egypt, he became interested in the Coptic Church, visited ancient sites, and began learning Arabic, but due to lack of funds and dangerous conditions, he failed to reach Ethiopia. He returned to Europe, and in 1665, lived and studied for a time in Italy where he converted to Roman Catholicism; he had concluded that any common ground between the Lutheran and Ethiopic churches was unconvincing. This was much to the dismay of his Lutheran colleagues, especially Ludolf, and led to an enmity between the two that lasted the rest of Wansleben’s life.

Wansleben moved to Paris and in the service of the French Consul Jean-Baptiste Colbert, minister to Louis XIV, he attempted a second expedition to Ethiopia in 1671-2. On his way there he made visits to via Cyprus, to Tripoli, Damascus and Aleppo. The following year he travelled extensively in Egypt, going up the Nile, but was again unable to reach Ethiopia, only managing to travel as far as Upper Egypt. However, he produced one of the earliest descriptive accounts of the famous White and the Red Monasteries near Sohag. During his travels in Egypt and the Levant, Wansleben collected for his patrons several hundred manuscripts in Coptic, Arabic and Ethiopic, which are now in collections in Paris, Florence and Rome.

Though Cambridge possesses none of the manuscripts Wansleben himself collected, evidence suggests that it was through the connection to Castell that his own notebook was acquired by the Library. Edmund Castell (1606-1686) studied at Emmanuel and St. John’s Colleges, then entered the Church. He acquired a knowledge of Arabic and assisted Brian Walton, the noted Bishop and scholar, with his ambitious project to print the famous Polyglot Bible, published in 1655-7. This publication became both a scholarly and commercial success and encouraged by this, Castell embarked on his own long and complex endeavour to print his Lexicon Heptaglotton, a dictionary in Hebrew, Samaritan, Chaldee (Aramaic), Syriac, Arabic, Ethiopic and Persian languages, published in 1669.

In 1666, Castell had been appointed to the Sir Thomas Adams Chair of Arabic in Cambridge and after his death volumes from his own book collection came to the Library. These include a notebook containing notes in Castell’s own hand (Ms Dd.6.4), and a closer look at the Wansleben manuscript reveals that on the recto of opening leaf there are also notes by Castell. Both of the volumes also contain the identical bookplate (from the engraving of William Jackson), which, although found in other volumes which came to the library around this date, does suggest a common former ownership.

Perhaps Castell retained Wansleben’s volume of notes with his own books from the time of their fruitful friendship in London. It seems most likely that Wansleben had copied some of these manuscript notes for Ludolf but they were left behind, either because they had already been used in Ludolf’s publications or because they would be of use to Castell in his own work.

The greatest significance of this manuscript volume of Wansleben’s notes, including the correspondence between Abba Gorgoryos and Ludolf, lies in the unique link it forms between the Library’s collections and the very origins of the study of Ethiopic as an academic subject in seventeenth century Europe.

References

Bausi, Alessandro, Allesandro Gori and Denis Nosnitsin with assistance from Eugenia Sokolinski. Johann Michael Wansleben’s manuscripts and texts. An update, in Essays in Ethiopian Manuscript Studies (Supplement to Aethiopica 4), Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2015, 197-243.

Dillmann, August. Catalogus codicum manu scriptorium bibliothecae Bodleianae Oxoniensis, Pars VII Codices Aethiopici. Oxford, 1948.

Hamilton, Alastair. Johann Michael Wansleben’s travels in the Levant, 1671-1674: an annotated edition of his Italian report. Leiden: Brill, 2018.

Hamilton, Alastair. The Copts and the West, 1439-1822. Oxford, OUP, 2006.

Norris, H.T. Professor Edmund Castell (1606-85), orientalist and divine and England’s oldest Arabic inscription. . Journal of Semitic Studies, 1984, 29(1), 155-67

Smidt, Wolpert G.C. Gorgoryos and Ludolf : The Ethiopian and German Fore-Fathers of Ethiopian Studies: an Ethiopian scholar’s 1652 visit to Thuringia. Cultural research in Northeastern Africa : German histories and stories, 10-25.

Ullendorf, Edward and Wright, Stephen G. Catalogue of Ethiopian manuscripts in the Cambridge University Library. Cambridge, CUP, 1961