Blackout: war time school life

On 25th August 1939, the German pre-dreadnought battleship Schleswig-Holstein, under the pretext of making a courtesy visit, sailed into the Port of Gdansk, anchoring 150m from Westerplatte (a peninsula in Gdansk, Poland, located on the Baltic Sea, where after 1921 the League of Nations granted Poland the right to install a garrisoned ammunition depot). Their orders were to launch an attack on Westerplatte on the morning of 26th August. Due to the Polish-British Common Defence Pact signed on 25th August, Hitler rescinded his orders. The battleship stayed in the port, Polish defences were strengthened (the attack anticipated already for some time). During the early morning of 1st September, the guns fired an assault on Westerplatte. The German generals carrying out the assault thought it would take 10 minutes at the least or a few hours at the most to win Westerplatte – it took seven days before the white flag appeared. The Battle of Westerplatte is often described as the opening battle of World War II, but for Poles, it became one of the symbols of the Polish struggle for independence. Westerplattes’ defence inspired the Polish Army and people even as German advances continued elsewhere. Beginning 1st September 1939, Polish Radio repeatedly broadcasted the phrase that made Westerplatte such an important symbol – “Westerplatte fights on”.

How strange to think we are re-living this history yet again. There is another power in today’s world that thought attacking and conquering a neighbouring country will take a few days and have been proven wrong. Every day we are waiting now to hear if Ukraine fights on.

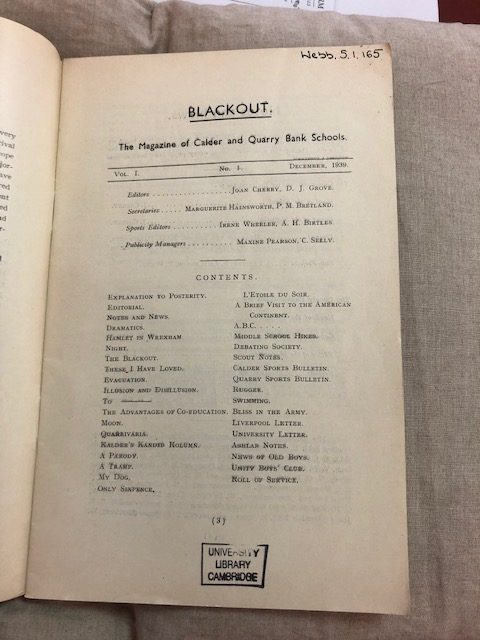

But let’s go back to history. Not only Westerplatte fought on – all over Europe, people had to adapt to a life in a new reality – the reality of war. The fear that German bombing would cause civilian deaths prompted the British government to launch an evacuation program. Children and mothers with infants were evacuated from British towns and cities to rural locations considered to be safe. Evacuation was voluntary, nevertheless the fear of bombing, the closure of many urban schools, and the organised transportation of school groups helped persuade families to send their loved ones to live with strangers not only in England, but also in Canada, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand and the United States. Operation Pied Piper began on 1st September 1939 and officially relocated more than 3.5 million people. The responsibility for the children fell on volunteers and teachers. There is ongoing research looking into the wellbeing and trauma all evacuees went through, but here in front of me I have an account from December 1939 found amongst the school magazines. “Blackout” was a magazine of Calder and Quarry Bank Schools, evacuated from Liverpool to Wrexham. In Explanation to Posterity, we read; “At 5:45am on Friday, September 1, 1939, German troops invaded Poland. [This prompted my long introduction about Westerplatte]. At 11:00am on September 3, Britain honoured her pledges to the latter state by declaring war on the Third Reich. At the same time and as the direct consequence, the evacuation of Caldar and Quarry Bank High Schools from Liverpool began. By the end of the following day more than six hundred boys and girls were comfortably billeted in Wrexham, Denbighshire. Since then we have shared with the boys and girls of that town the County School premises in Grove Park and Chester Road, where we are receiving our wartime education”. (Blackout, Vol. 1 No 1, December, 1939; CUL Webb.5.1.165). The Heads of the schools, Miss Macrae and Mr. Bailey were dealt a hard card to play. They were responsible for the welfare of more than seven hundred children removed to a strange and unfamiliar town and placed in the care of foster families. The Grove Park School, with Miss Gower-Jones and Mr. D.J. Lloyd as head teachers, was used for educational purposes.

Being published in extreme and challenging times, the magazine and its preparation recalls and contrasts the normality of Liverpool life of the previous term. Nevertheless, as the Editors put it nicely using a quotation from a popular song, “they can’t black-out the moon” and in their own words on the pages of this magazine, they have proven that both schools not only can carry on, but also can make considerable progress. There was time for a ‘movie party’, visit to the local factories, a play production and a very short visit of Miss Force from the United States. There was also time for poetry, prose and of course for sport. The difference from the ordinary school magazine brings News from the Front and In Memoriam. According to sources, the returns of evacuees began in 1944, and evacuation officially ended in March 1946. Sadly, the library only holds one copy of Blackout, so we cannot follow the wartime lives of their students more closely, but if it sparked your interest, Blackout is now available to see in the Rare Books reading room.

Blackout, Vol. 1 No 1, December, 1939; CUL Webb.5.1.165

On my arrival in Liverpool as a refugee from Germany , just before outbreak of the 2nd world war, Mr Bill Bailey, head-

Master of Quarry Bank school, arranged for 2 of his former pupils to start teaching me English at home since the school was about to be evacuated. I shall be forever grateful to Mr. Bailey since I knew no English and this was the start of learning it until the school returned from Wrexham to Liverpool in spring 1940.