The Polonsky Foundation Greek Manuscripts Project: A final farewell from the Conservation Team

Conservation work on the Polonsky Foundation Greek Manuscripts Project was completed way back in 2021 but our conservators have recently taken the time to reflect on their achievements. The raw numbers are impressive enough: they treated 240 manuscripts, with 7 manuscripts completely rebound. 229 items were also rehoused, including 97 items in bespoke handmade enclosures. Since the end of the project the conservators have moved onto other exciting projects and roles. As a final farewell from the conservation team we have asked Shaun, Sam and Marina to share some of their memories, learnings and favourite manuscripts from the project.

Shaun’s reflections

As this is the last blog post from the conservation team, I wanted a chance to say that the whole success of the project was down to the dedication, diligence, and skill of the amazing project conservators. For me, the opportunity to provide support and encouragement to the team has been a pleasure and it’s been very rewarding to watch them develop.

During the project, the highlight for me was working with my colleagues on the rebinding of seven manuscripts, which gave us the chance to develop a binding structure for Greek manuscripts that was mechanically sound and sympathetic to the cultural context of where and how they were originally produced.

The projecting endbands are one of the distinct features of a genuine Greek-style binding, along with the textblock being cut flush to the boards. This allows the endband to travel seamlessly from the textblock onto the edges of the boards where they are anchored giving mechanical integrity to the binding. This was a particularly challenging element of our design because our new bindings have squares to the boards to protect the textblock from abrasion.

Our first solution to the addition of squares was to sew a single primary endband to the textblock between the boards and the secondary Greek-on-two-cores endband over this, which was anchored the traditional way. This worked well, however, we felt like we could improve on this design so on the next rebinding we made some further changes. We adapted the anchor points to the boards by removing small channels to the outer face of the boards at the spine edge to accommodate one of the cores; this allowed us to execute the Greek-style endband in one go. This further adaptation proved to be a far better solution for such an important structural element of the rebindings. My favourite manuscript in the project was Trinity College, Cambridge, B.7.1. I worked on the rebinding of this manuscript with Marina and it was very rewarding to see the final outcome.

Sam’s reflections

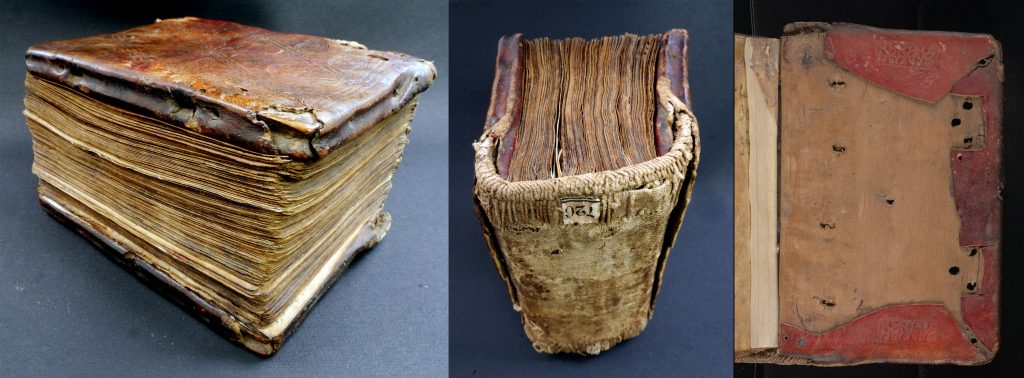

At the beginning of the project I had never worked on a Greek-style binding, so I learnt a lot and fast. What was most fascinating to me was not only the differences between Greek-style and Northern European bindings but also the sheer variety within the Greek style. My favourite binding from the project is CUL MS Add.720, a late 10th or early 11th century Gospel book which displays many of these distinctive Greek-style features. They include the wooden boards and grooved edges onto which the classic Greek endbands extend, the smooth spine with a textile transverse spine lining which has been revealed by the loss of the spine leather, and the braided straps and metallic pins that would have held the book closed but have been lost although the holes they were laced through remain. The binding is a very ergonomic size, fitting nicely in the hand, and is covered in a deep red tanned skin.

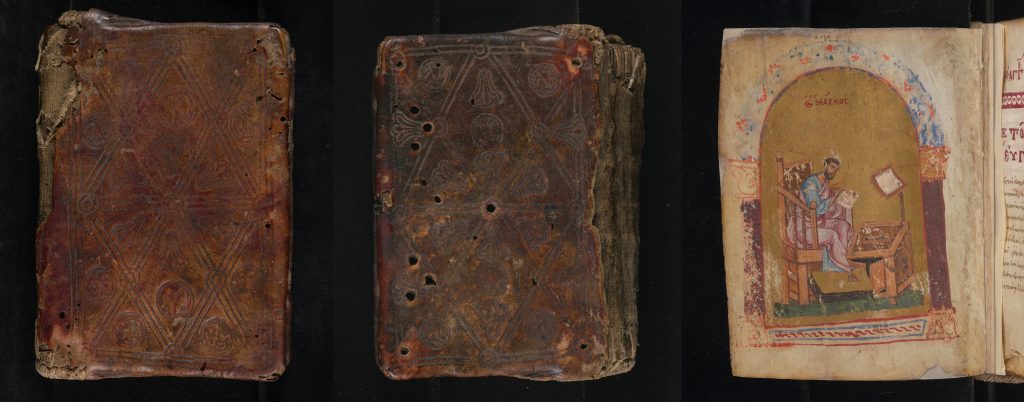

The blind tooling on the boards reveals the actions of the binder, as the tooling on the left board is the correct way up but is upside-down on the right board. This shows the binder likely started on the left board before flipping the book head-to-tail and then tooling the right board upside-down. This connection to people from the past makes this binding special.

Left: The left board showing the rich red tanned skin and blind tooled decoration. Centre: The right board. See that the tooling is upside-down compared to the left board. Right: A full-page illumination showing Mark writing at a desk.

To top it all off the manuscript also has some very special full-page illuminations, the best examples being of Mark, Luke with Saint Paul and the Holy Family.

Marina’s reflections

The project was a great learning opportunity for me. It was my first time working in a British institution, as part of a big team, and in a digitisation project. The main aim of the project was to stabilise Greek manuscripts prior to digitisation, nevertheless the conservators had the chance to do some more in-depth treatments.

Because of time constraints and funding, it is not always the case that a digitisation project can accommodate time for Continuing Professional Development (CPD). I was lucky that this particular project had some CPD built in and that was one of its the best characteristics. I was able to rebind two manuscripts, which helped develop my understanding of the structures involved, the particularities of each object and what the object needed from its new structure.

CUL MS Dd.4.42 was one of the manuscripts that was rebound during the project (and one of my favourites!). It is a 10th-century liturgical manuscript, a “Menology for December”, not very refined in style but with beautiful thick parchment pages. The existing binding was a rebinding, in a Western style, heavily damaged and not suitable for the parchment textblock. The book received a Greek-style binding with wooden boards, loop stitch sewing and projecting endbands. One of my challenges was to make the materials suit the book and give it the stability that it needed. The recessed design for the boards as Shaun has mentioned worked perfectly for the uneven gatherings. As conservators, we say each object is unique and requires unique assessment and treatment and this book is proof that adapting our approach to the needs of the book brings great results.

If you have been following our blogposts you will know that Shaun, Sam and Marina were not the only conservators to work on the project, so we would like to extend a huge thank you to Project Conservators Marie Renaudin and Cécilia Duminuco who were integral to the conservation project’s success.

Although it is sad to say goodbye to the Polonsky Foundation Greek Manuscripts Project, the conservation team have taken away new expertise and great memories of a very successful project. We thank you all for taking time to read our posts and follow our progress.

The Polonsky Greek Conservation Team.