The Crimean War letters of Captain Blackett

Alma Crimea

Sep th 21st

My dear Father,

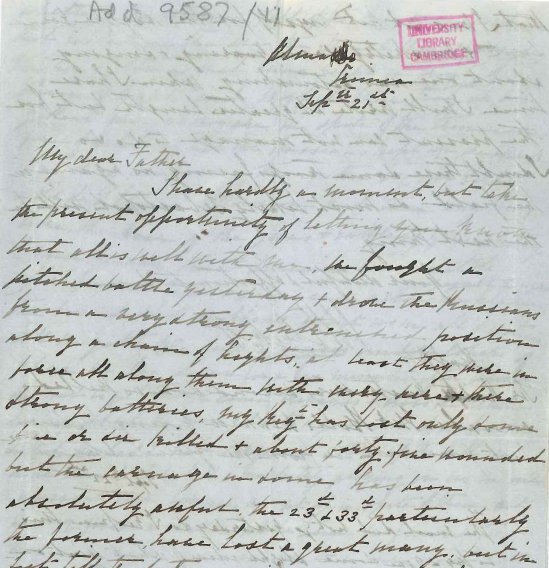

I have hardly a moment, but take the present opportunity of letting you know that all is well with me. We fought a pitched battle yesterday [and] drove the Russians from a very strong entrenched position along a chain of hights at least they were in force all along them with very here [and] there strong batteries, my Regt has lost only some five or six killed [and] about forty five wounded but the carnage in some has been absolutely awful the 23d [and] 33d particularly the former have lost a great many…..

With the no doubt welcome news that he is not to be numbered amongst the casualties, (‘in fact I look on it as only the interposition of a merciful providence that I was not hit myself’), Captain Christopher Edward Blackett (1826-1904) of the 93rd Highland Regiment (later of the Coldstream Guards) begins his account of the Battle of the Alma, fought on the 20th September 1854, in a letter to his father [Add.9587/11]. This letter is one of a series of 52 written by him to his parents during the Crimean War, with the majority of the letters (from June 1854 to April 1856) written from the field in the Crimea. Recently added to Janus (the online catalogue for Cambridge archives) by the manuscripts department, this collection (Add.9587), is one of a number of manuscript collections with relevance to the Crimean War (1853-1856) .

He adds a longer description of the battle to his letter the following day (22nd September) ‘to try and give you some slight idea of what went on’,

..the 1st Division immediately after formed line [and] advanced across the plain [against the right] the round shot dropping about us in all directions till we got to a line of fences under cover of which we lay down for a few minutes, after this we had to go through some orchards [and] cross the Alma during which the men got into a good deal of confusion so that we had to halt [and] reform [and] then up the hill we went round shot , shell, [and] musketry playing on us in one incessant roar, however we got up in spite of them not having fired a shot the whole time, we found the Russian Regts in column right in our front not more than some sixty yards from us and the way we dropped them with our Rifles was beautiful.

On the 25th October 1854 the 93rd Highland Regiment took part in the Battle of Balaclava, where they formed the ‘thin red streak topped with a line of steel’ described by the Times war correspondent William H. Russell, subsequently immortalised as the ‘thin red line’. In a letter to his father dated the 31st October [Add.9587/16], Captain Blackett describes how they faced the Russian cavalry,

…two Regts came on in a dense black column of I should say twelve or fourteen very strong squadrons [and] bore right down on us. We were in line with Turks, on either flank, who on seeing the Cavalry took to their heels, but were rallied by some of our Officers driving them back, as soon as the enemy got within about five hundred yards we opened a fire of Minié rifles on them that some began to drop their horses, the nearer they got the hotter it became for them till when they arrived to within about three hundred yards they edged off to the left and fairly cut, before and after this affair we had a good deal of both shot [and] shell but during the whole day our loss amounted to but three men wounded.

Map showing Battle of Balaclava showing the Russian cavalry advance towards the 'thin red line.' Taken from Kinglake, Alexander William, The invasion of the Crimea: its origin, and an account of its progress down to the death of Lord Raglan, Vol. IV, William Blackwood: Edinburgh, 1868 (RA.24.42)

After describing the Charge of the Heavy Brigade he continues,

We remained after this looking at each other for at any rate an hour [and] why the Russians did not bring forward the Infantry and compell us to give up our ground, for it would have been quite out of the question to hold it against the odds they could have brought. I can not imagine but fortunately for us they did not except perhaps they took us to be stronger than we really were…

Eventually ‘by and by our longing eyes were gladdened by the sight of columns of red uniforms descending the hills’; the arrival of reinforcements from Sebastopol. They ‘naturally imagined that the Russians would in the course of half an hour be driven from the positions they had captured in the morning’ from the Turks, but ‘as soon as dark our troops drew off in the direction of Sebastopol leaving to our unspeakable disgust the heights in possession of the enemy’.

The most famous and notorious incident of the Battle of Balaclava, the famous ‘Charge of the Light Brigade’, took place out of sight of the 93rd Regiment and Captain Blackett but he tells his father that, ‘every one who saw it says it was neither more nor less than driving brave men on to certain death’. After listing the names of a few of the officers who were killed he adds,

…you may imagine what a desperate thing it was when General Eastcourt told me that when the Light Brigade advanced he did not expect to see one of them return, Lord Raglan may say what he likes in dispatches, but you may depend on it I have told you the real feeling in the army out here…

During the winter of 1854/55 the troops endured poor conditions living under canvas. On November 14th hurricane force winds caused considerable damage, ‘one of the most frightful storms it has ever been my lot to witness’ [Add.9587/19]. On the 24th December he is writing to his father that,

Extract from MS Add.9857/25. It is written in the form of 'cross writing' which was used to save paper, paper being expensive at the time. Cross writing was also used to save on postage, as postage was charged per page. The transcription begins at the end of the first line.

The weather though very wet and disagreeable is by no means severe as yet in the way of frost [and] snow, the climate though is so variable that one can not depend on it for four and twenty hours at a stretch, no huts from home have yet made their appearance, and owing to the most abominable mismanagement on the part of Sir Colin Campbell and our Colonel, who is one of the greatest dunder-heads in creation we have not yet been permitted to make huts for ourselves, had we been permitted to do so we would long ago have been quite comfortable…..instead of being in a cold damp tent… [Add.9587/25]

By January 4th, 1855 he is writing; ‘Winter is regularly on us. The snow is a foot deep and still falling fast’. He reminds his mother that he wanted ‘a couple of large worsted night-caps to be sent out’ [Add.9587/26]. Later the same month he is again writing to his mother lamenting the lack of organisation and the resulting hardship for the troops, and contrasting the British unfavourably with the French,

Sebastopol is as far from falling as ever, in fact till we get a fresh army in Spring you must not look to hear of its being taken….here we must remain for the Winter, everything connected with the siege has in fact been mismanaged by us though not by our noble allies… our poor fellows in front are very miserable for want of proper covering in this inclement weather, they come out of the trenches, wet to the skin, [and] instead of having any warm dry place to go to they have to creep into a wretched damp tent where they have no means of drying themselves, their clothing is very insufficient, and their provisions consist almost entirely of salt meat; an excellent thing in moderation but by no means condusive to health when men have nothing else to eat, the enemy do us little harm comparatively, but the number of men we lose from sickness is terrible. [Add.9587/28]

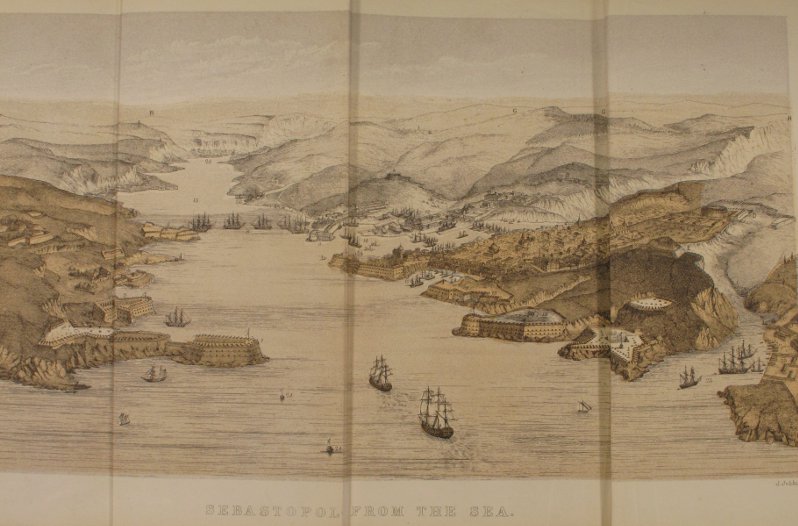

Panorama of Sebastopol. The Malakoff, which Blackett mentions in letter MS Add.9857/36 (see below), is on the hill in the centre of the picture. The Redan (also mentioned in MS Add.9587/36) is on the next hill to the right. The panorama is taken from Kinglake, Alexander William, The invasion of the Crimea: its origin, and an account of its progress down to the death of Lord Raglan, Vol. III, William Blackwood: Edinburgh, 1868 (RA.24.41)

By late February though he is writing to his father that, ‘it is somewhat premature of the people at home to [put?] us down as no longer existing as an efficient force…we are…certainly by no means as bad as is represented by many of the newspaper correspondents…’, and he cheerfully adds,

‘…in all my life I never was in better health. People may talk of the uncertain climate of England but let them come here, the Crimean weather is as uncertain as the fancies of a Miss in her ‘teens…’ [Add.9587/31]

In a letter to his mother on the 8th March he reports that, ‘The condition of the troops here is decidedly better regulated than was the case some little time ago. As to the siege, the old story, nothing going on…’ although not entirely without incident,

‘…when up in the front I need frequently to take a glass [and] go along the heights of Inkerman, on the opposite side of the valley one could plainly see the enemy [and] when the wind was favourable I have on more occasions than one heard their bands playing, besides this one used to be reminded of their proximity in a less agreeable manner as they had a battery on the opposite side of the Tchernaya, from which whenever they saw a party of people who were worth a shot, a long white puff of smoke would issue, followed by the angry whizz of a shell, very fortunately though the distance was so great that they seldom hit anyone though by giving their guns great elevation they used occasionally to pitch their shot right among the tents of the Guards.’ [Add.9587/32]

Only one of Captain Blackett’s letters survives for the period between March and September 1855 (written in July), in which he sounds distinctly war weary, ‘…marching [and] fighting in the field I like, but this siege work is tiresome in the extreme [and] I wish with all my heart it was at an end.’ But on the 10th September 1855 he is able to write to his father that,

‘Sebastopol at last is in possession of the allies, the day before yesterday at noon we stormed [and] after a most terrible fight the French got possession of the Malakoff tower in consequence of which the enemy abandoned the whole of the south side, setting fire to it during the night, [and] blowing up or sinking all their men of war. I rode into the town yesterday which is all knocked to pieces by our shot [and] shell, the losses on both sides have been very great, the French [and] ourselves have I should think ten thousand hors de combat and to judge by the number of dead I saw yesterday I should put the Russian casualties at a still greater figure, the Guards were in reserve, [and] had the enemy not gone during the night we were to have [been] in front yesterday morning [and] put at the Redan.’ [Add.9587/36]

With ‘Sebastopol…in the hands of the allies it is I think possible that some of us may get leave to go to England for a little during the Winter…’, but in the event Captain Blackett was to remain in the Crimea with the allied armies until March of 1856.

Photograph showing the ruined interior of the Redan after it had been deserted by the Russians. Photograph from Royal Commonwealth Society collections, reference Y3011A/1.

All the collections concerning the Crimean campaign may be consulted in the Library by anyone holding a reader’s card valid for the Manuscripts Reading Room.