Charming creepy-crawlies in the Middle Ages

Animals often crop up among the medical recipes in the over 180 medieval manuscripts that Cambridge University Library is currently conserving, cataloguing, and digitising in its new project Curious Cures in Cambridge Libraries. Texts about animals especially show a concern for warding off unwanted bugs, worms, and rodents, all creatures that could potentially endanger people’s livelihood and health. In order to repel such ‘vermin’ medical practitioners regularly turned to the supernatural. In this blogpost we explore some of the magical practices that were used for countering animal infestations and infections—mostly including cruelty-free methods!

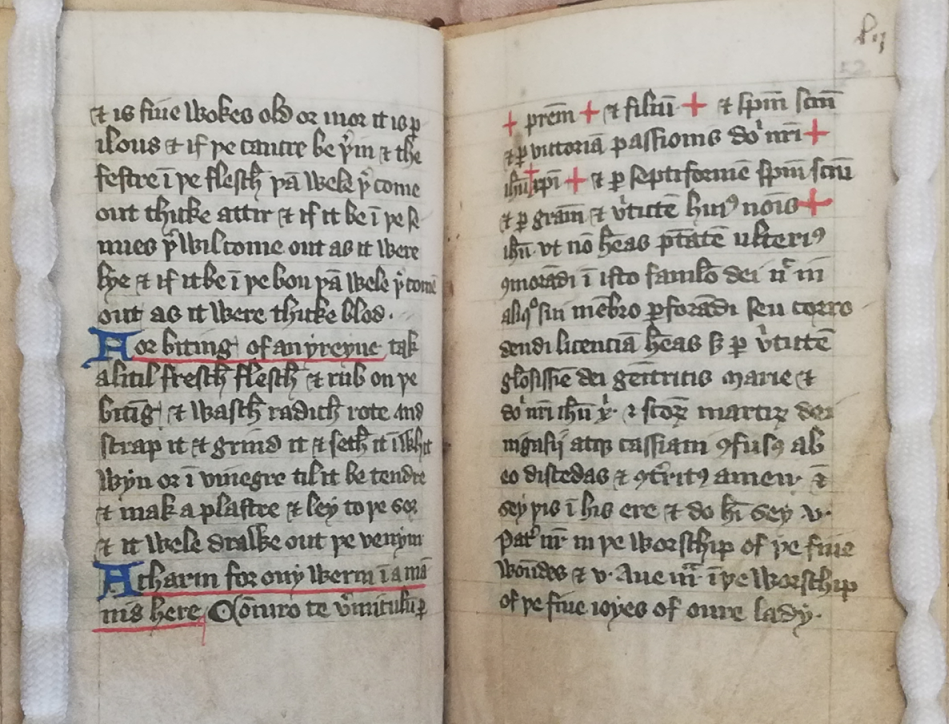

Among the many medical recipes in a fifteenth-century manuscript for a physician, known as a ‘leechbook’ (Cambridge, University Library, MS Add. 9308), is a magical spell or ‘charm’ for casting worms out of a patient’s ear. These ‘ear-worms’ refer to earwigs, insects that were commonly believed to crawl and live inside the human ear. To extract them, you need to recite a charm in the patient’s ear using a formula that invokes Christ, the Virgin Mary and, for reasons that are not entirely clear, the martyr saints Nicasius and Cassian:

A charm for any worm in a man’s ear:

“I conjure you worm through the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit and through the victory of the Passion of our lord Jesus Christ and through the sevenfold Holy Spirit and through the grace and virtue of this name Jesus, that you do not have the power to dwell any longer inside this servant of God or the freedom to pierce or gnaw any of his body parts, but through the virtue of the most glorious mother of God Mary, and our lord Jesus Christ and the holy martyrs Nicasius and Cassian, may you depart from him thwarted and broken. Amen”. And say this in his ear and make him say five Paternosters in the worship of the Five Wounds and five Hail Marys in the worship of the Five Joys of our Lady.

A charm for ony werm in a mannis here: Coniuro te vermiculum per + patrem + et filium + et spiritum sanctum et per victoriam passionis domini nostri + ihesu + Christi + et per septiformem spiritum sanctum et per gractiam et virtutem huius nonimis + ihesu ut non habeas potestatem ulterius commorandi in isto famulo dei nec in aliquo sui membro perforandi seu corrodendi licenciam habeas sed per virtutem gloriosissime dei genitricis marie et domini nostri ihesu Christi et sanctorum martirum dei nigasij atque cassiani confusus ab eo discedas et contritus amen

and sey þis in his ere and do him sey .v. Pater noster in þe worship of þe five woundes and v. Ave maria in þe worship of þe five ioyes of oure lady.

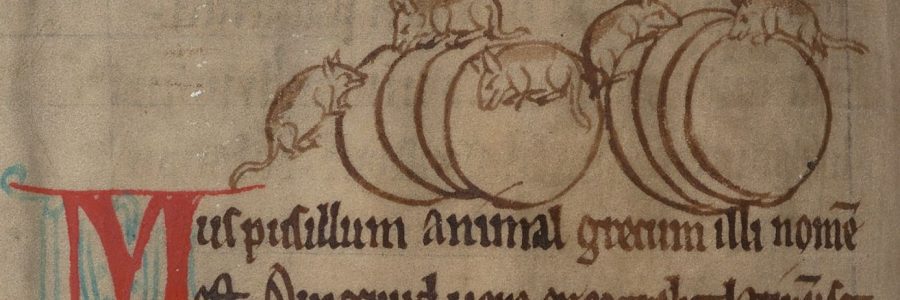

A similar exorcism-like formula is part of a charm that opens another fifteenth-century collection of medical recipes (Cambridge, Gonville and Caius MS 457/395), but this time it is designed to drive away rats. Like the previous charm, it invokes the Virgin Mary who, according to the text, all creatures – including rats – should obey. It also invokes St Nicasius, already mentioned above, and St Gertrude of Nivelles, who was commonly invoked against rodent infestations and who was typically portrayed surrounded by mice or rats in medieval images:

To gather rats and drive them from a place:

“I command all the rats that are in this place, inside and outside, by the virtue of our dear Lady who carried Jesus, and who all creatures should obey, by the virtue of St Gertrude that good clean holy virgin to whom God granted the favour that no rats shall ever dwell in the place where her name is spoken, in the virtue of St Nicasius that holy man to whom God gave the favour that no rats shall ever dwell in the place where his name is spoken, Lord God of Hosts, and by the virtue of the Holy Spirit, I command all the rats that are here in this place that you flee this place and go away so that no rats dwell in this place. Lord God of Hosts, may you keep this place from all evil creatures and from all rats and all other misfortunes. In the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit. Amen.”

ffor to gedryn Ratownys and dryve þem from a place: I comaunde alle the Ratonys þat arn in this place withinne and withoute and be þe vertu off oure swet lady þat Jhesu bar abowte that al creatorys owyn ffor to lowte and be þe vertu off seynt Geretrude þat good holy mayde clene þat god grauntyd here þat grace þat neuer no Ratonys xulden dwelyn in þe place that her name is nemelyd in And be þe vertu of seynt Casse þat holy man that god ȝave hym þat grace þat ther xuld never no Ratonys dwellyn in the place that hys name was nemelyd in dominus deus sabaot and be the vertu off the grete gost I comaund alle the Ratonys þat arn here in this place that ye fflee this place and goo hense that no Ratonys dwellyn here in this place dominus deus sabaott [sic] be the whiche this place ye kepe ffrom alle wykkyd whehtes and ffrom alle Ratonys and alle odyr aventorys In nominee patrys et filij et spiritus sancti Amen

Whether the charm was successful seems doubtful since a rodent has heavily gnawed the same page on which the text was written.

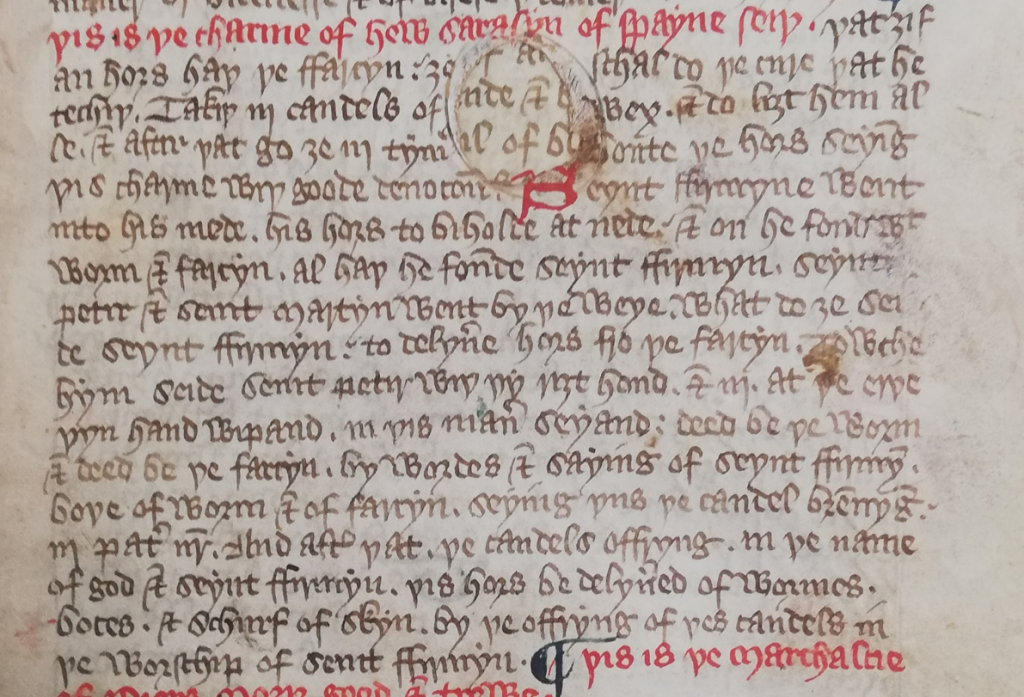

Charms were not only used to protect humans from vermin, but also the animals that they kept for their livelihood. This can be demonstrated by a fifteenth-century manuscript with medical recipes for treating ailments in horses (Cambridge, University Library, MS Dd.4.44) which contains several charms against the worms that were believed to cause ‘farcy’—a disease of the skin and respiratory tract that is often fatal to horses. One text instructs you to light three candles and recite a charm while walking around the horse, recounting a story about Fermin, a Spanish martyr saint whose only link with horses may be the fact that he, according to medieval legend, was dragged to death by a bull—another hoofed mammal. The charm recounts that St Fermin once found worms that cause farcy on his horse and asked St Peter the Apostle and St Martin of Tours – a patron saint of horses – for advice. Subsequently, St Peter taught him how to effectively curse the worms away:

This is the charm that Hugh Sarasyn of Spain said: if a horse has farcy, you should do the cure that he teaches. Take three candles of wax and light them, and after that you should walk around the horse three times while saying this charm with good devotion: “St Fermin went to his field to look after his horse in need: and on his horse he found worms and farcy. All did he find. St Fermin, St Peter and St Martin walked on the road. “How”, said St Fermin, “do you relieve a horse of farcy?”. To which St Peter replied: “With your right hand beat the earth three times, saying the following: “Dead be the worm and dead be the farcy through the words and commandment of St Fermin, may the horse be delivered of both worms and farcy”””. Recite three Paternosters with a candle burning. And after that, offering the candles up in the name of God and St Fermin, the horse will be delivered of worms, swellings, and scurf by offering these candles up in the worship of St Fermin.

þis is þe charme of hew sarasyn of spayne seiþ. þat ȝif an hors haþ þe ffarcyn: ȝe schal do þe cure þat he techiþ. Takiþ iij candles of wex. and do liȝt hem alle aftir þat go ȝe iij tymes about þe hors seying þis charme wiþ goode deuocioun: Seynt ffirmyne went into his mede . his hors to beholde at need ; and on he fondwt worm and farcin . al haþ he founden seynt ffirmyn . seynt Petir and seint Martyn went by þe weye. What do ȝe seide seynt ffirmyn: to delyvere hors fro þe farcyn. To wche hym seide seint Petir wiþ þy riȝt hond. and iij. at þe erþe þyn hand wipand. in þis maner seyand: deed be þe worm and deed be þe farcin . by wordes and saying of seynt ffirmyn . boþe of worm and of farcyn . seying þus þe candel brennyng ; iij pater noster. And after þat . þe candels offryng . in þe name of god and seynt ffirmyn . þis hors be delyvered of wormes. botes and schurf of skyn . by þe offryng of þes candles in þe worschip of seint ffirmyn.

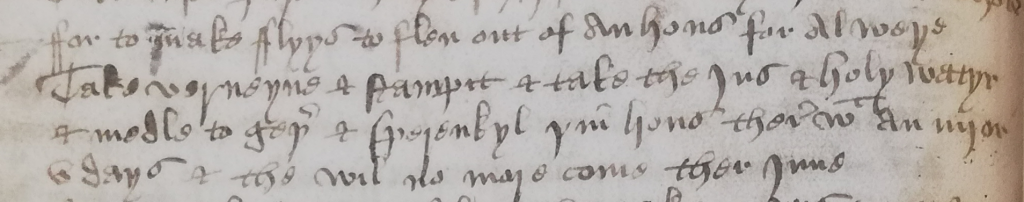

Charms were not the only supernatural method with which vermin was combatted. The collection of recipes in Cambridge, Gonville and Caius College, MS 457/395 prescribes a relatively simple method for clearing your house of flies that is based on the purifying powers that were attributed to holy water. This recipe instructs you to crush the herb vervain (verbena), mix its juice with holy water, and sprinkle your house with the resulting liquid for five consecutive days:

To make flies flee a house forever:

Take vervain and mash it and take the juice and holy water and mix them together and sprinkle your house therewith for four or five days and the flies will no longer come back inside.

ffor to make flyys to flen out an hous for alweye: Take verveyne and stamp it and take the jus and holy watyr and medle to geþer and sperenkyl þin hous therewith an iiij or v days and the wil no more come ther inne

While these practices may seem a long way from current methods of curing infestations and infections, they show that medieval people recognised the danger that certain animals could pose if left unchecked in houses and bodies and responded to them as forms of evil that could be countered through religious belief and ritual. Whether through invoking saints or using holy water, these texts reflect some of the complex symbolism with which medieval people viewed their world.

These are just a few of the many magical recipes that can be found in our project’s manuscripts. Please keep an eye on this blog for future posts about our progress and findings, and the Cambridge Digital Library where digitised versions of our project’s manuscripts will be uploaded soon.