The Rose Book Collecting prize 2022: Illustrated books from early-modern Japan

The Rose Prize is awarded annually to a current student of the University, for a coherent collection on any subject from any period. The winner for 2022 was Joseph Bills, a student on the MPhil in Japanese Studies course, who has just been announced as joint winner of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association national book collecting prize! Joseph has written this blog to share with us his thoughts on putting his collection together.

What makes a good book collection? Is it its size, its monetary value, its provenance, its range, its completeness? It could be any or all of these things. But for me, a good book collection reflects the collector. Their personality, their interests and their goals undeniably affect the books they include, as do the circumstances under which they start and continue searching for new titles. This is why I believe that you cannot simply judge a book collection by the quality or rarity or monetary value of its contents. Why certain works were brought together by a certain person is as important as what those works are. So you have to ask, by building a collection what is a collector trying to say?

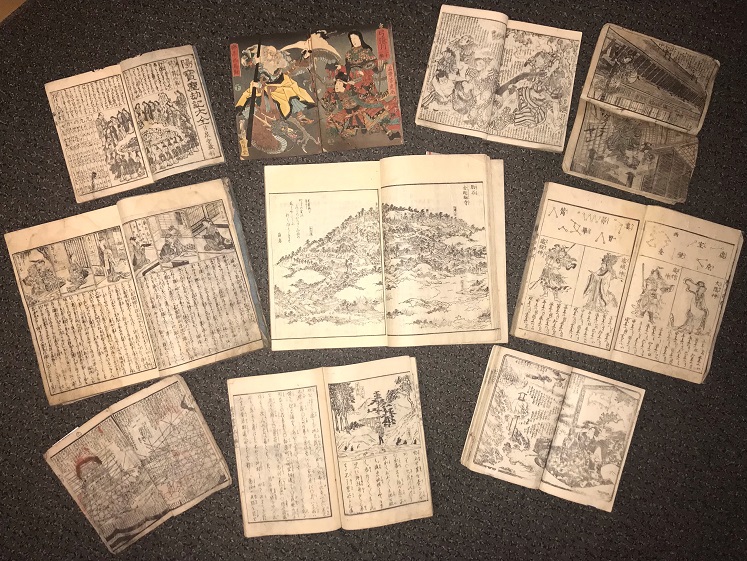

Recently the Cambridge University Library held its sixteenth Rose Book-Collecting Prize for student book collectors, and I am fortunate enough to have been awarded first place. I entered the running with the title: ‘Illustrated Texts as Living Objects in Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Japan’, showing a number of the books I have acquired over my year abroad in 2019/2020 and after. The books I collected share a number of features. The first is that they are all illustrated. This is not to say that they are all children’s books. The publishing industry of early modern Japan was replete with illustrated texts meant for all audiences, from travel guides to textbooks to short novels to art books. The modern association between picture books and children was not present at the time. Furthermore, I chose to focus on illustrated texts as part of my undergraduate dissertation project so it is no surprise that these were the materials that drew my eye. The second feature that connects my collection is that the books are all commoner literature. I made a concerted effort to focus on what would be read by ordinary people in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, avoiding the high literature that would only have been consumed by an educated elite. Part of the reason for this was monetary, as I was on a student budget. But beyond this, I find it enticing to connect with the reading materials of the masses. What was popular, what genres sold well, which authors were best sellers? Reading what a population found interesting brings you one step closer to their culture, and so I wanted my collection to reflect the unique sensibilities of that world.

Most importantly however, the books I collected all display in some way their own personal histories. They have notes written in their margins or owners’ names stamped on their covers, they have been coloured in, they have been rebound, and in some cases they are deliberate forgeries. Often I only own half of a two-volume set, or in the case of Shiranui Monogatari 白縫譚 (1849–1885), 6 volumes of 180. But these things do not lower the value of my collection, they enhance it. By including items that are in some way unique I can show how a book is more than just the sum of its contents. It is a physical object that has been touched and read by multiple people, and has travelled across the world to make its way to me. That object can connect different readers across time and distance, a young researcher in twenty-first century England with a child in nineteenth century Japan. My collection reflects not just the eclectic literary market of early-modern Japan but the people who took part in that market as well.

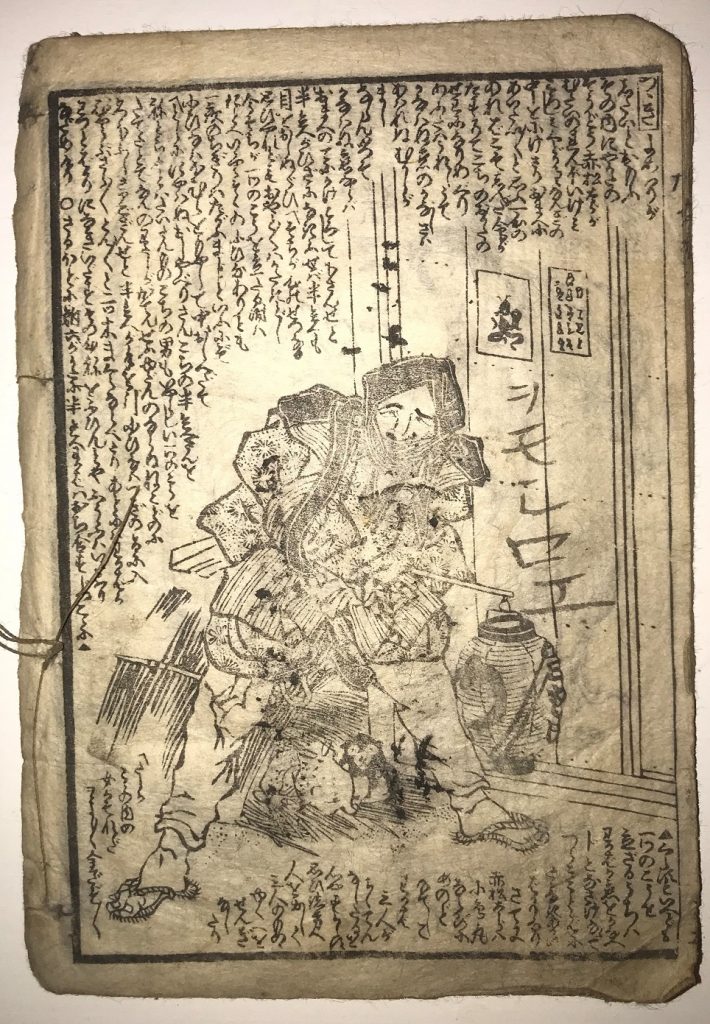

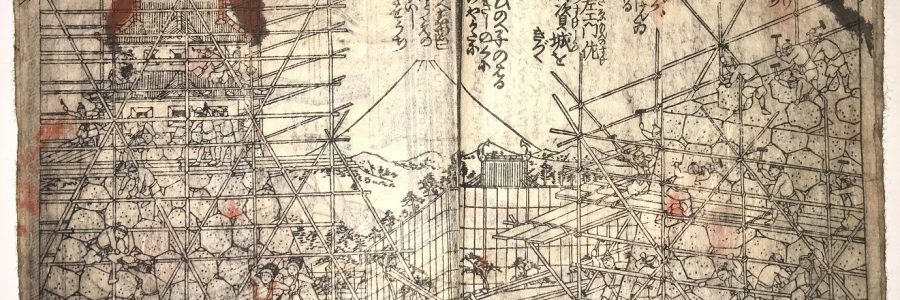

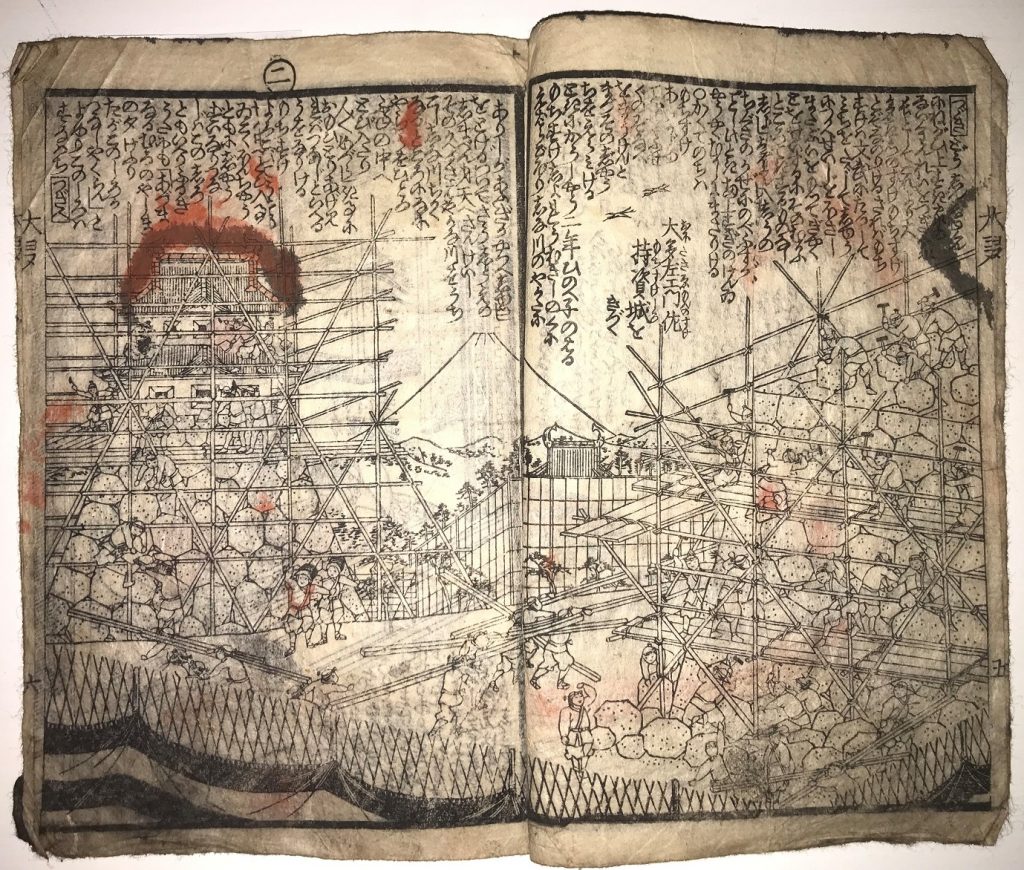

For example, some of my most prized items are two gōkan 合巻 (long-form illustrated books from the early–mid 1800s): Mukashi gatari tataso 昔語太多礎 vol. 1a (1850, fig. 1) by Nagashima Ikkaisha 長嶋一魁車 (n.d.) and Beni jitate onna daruma 紅染女達磨 vol. 3a (1816, fig. 2) by Tōzaian Nanboku 東西庵南北 (d. 1827). I do not own full sets of these works, only one of two volumes of the former and one of twelve volumes of the latter. They are both in poor condition. But they also both offer tantalising insights into the lives of the people who once owned them. Figure 1 shows how my copy of Mukashi gatari tataso has parts coloured in red. Gōkan were printed in monochrome, with the exception of their covers, but a former reader took it upon themselves to mark out crests, faces and, in this picture, fire. Not only does this make my copy unique, but it makes it a more vibrant example of Mukashi gatari tataso than one fresh out of the printing shop. Figure 2 is another example of a reader making changes to a book, but this time the previous owner has written in their reactions to the story in the margins. In figure 2 itself someone has written ヲモシロエ (面白エ, omoshiroe), which means “Fascinating!” across the page. On another folio showing a man chasing a woman up a ladder the person has written ダイテヤレ (抱イテヤレ): “Catch her, catch her!” As someone nowadays might vocalise their reactions when watching a film on television, this reader has immortalised their thoughts about the story and inscribed them onto the pages themselves. Again this renders my copy one-of-a-kind, a glimpse into the mindset of who was consuming early modern books as well as what they were consuming.

But let us circle back to my opening question – what do I want to say with my collection? I want to show the vibrancy and diversity of the book culture of early modern Japan, to communicate the vast array of different works that were produced at the time. I want to show what was popular among real people, what they wanted to read. But most of all, I want to show that books are more than just the sum of their contents. They are living objects, parts of people’s lives, and can carry those lives on their pages. Collectors often value the pristine, the complete and the scarce. But to me, these traits create books that are hollow shells. They lack the signs that come from being loved and pored over. It is as if no one ever touched them. So my collection promotes the opposite: the marked, the incomplete and the common. And through this I hope that it can connect us to the people of early modern Japan as well as their literature. Besides, is it not rarer to own a book that is totally unique, created through its interactions with the people that have owned it? This is the heart of what I want to say with my collection: every book is one-of-a-kind.

Joseph Bills (MPhil by Research, Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies – Japanese Studies), Trinity Hall, Cambridge . jab296@cam.ac.uk