Introducing the CUL Additional Fragments Project or Three Lessons in Fragmentology

A post by Dr Marie Turner.

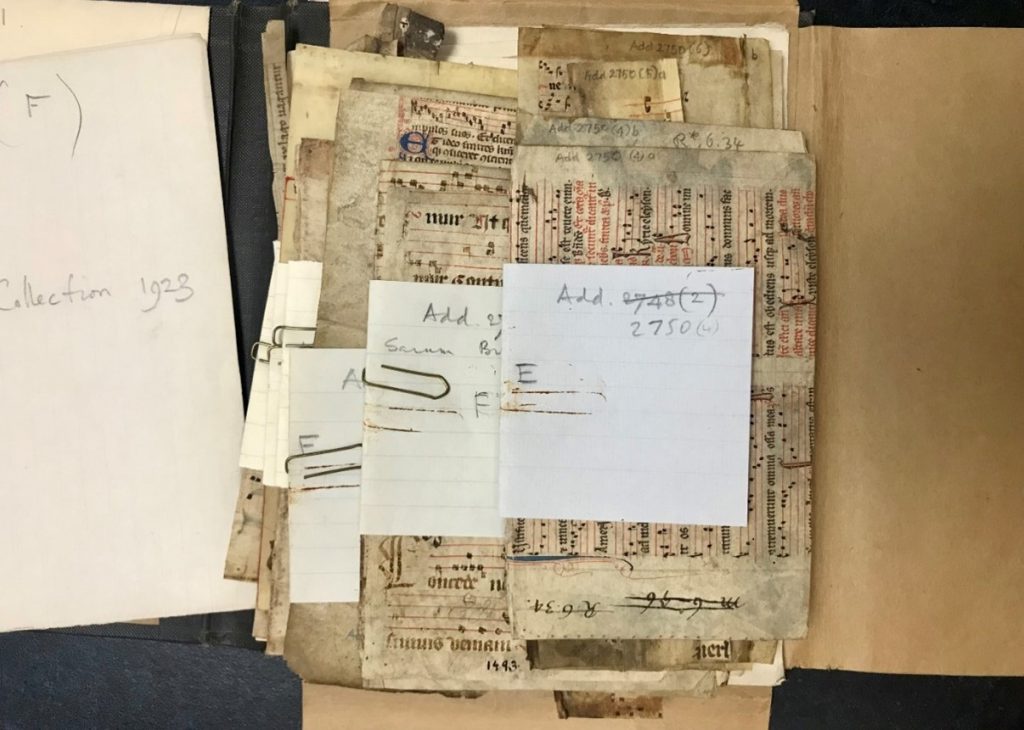

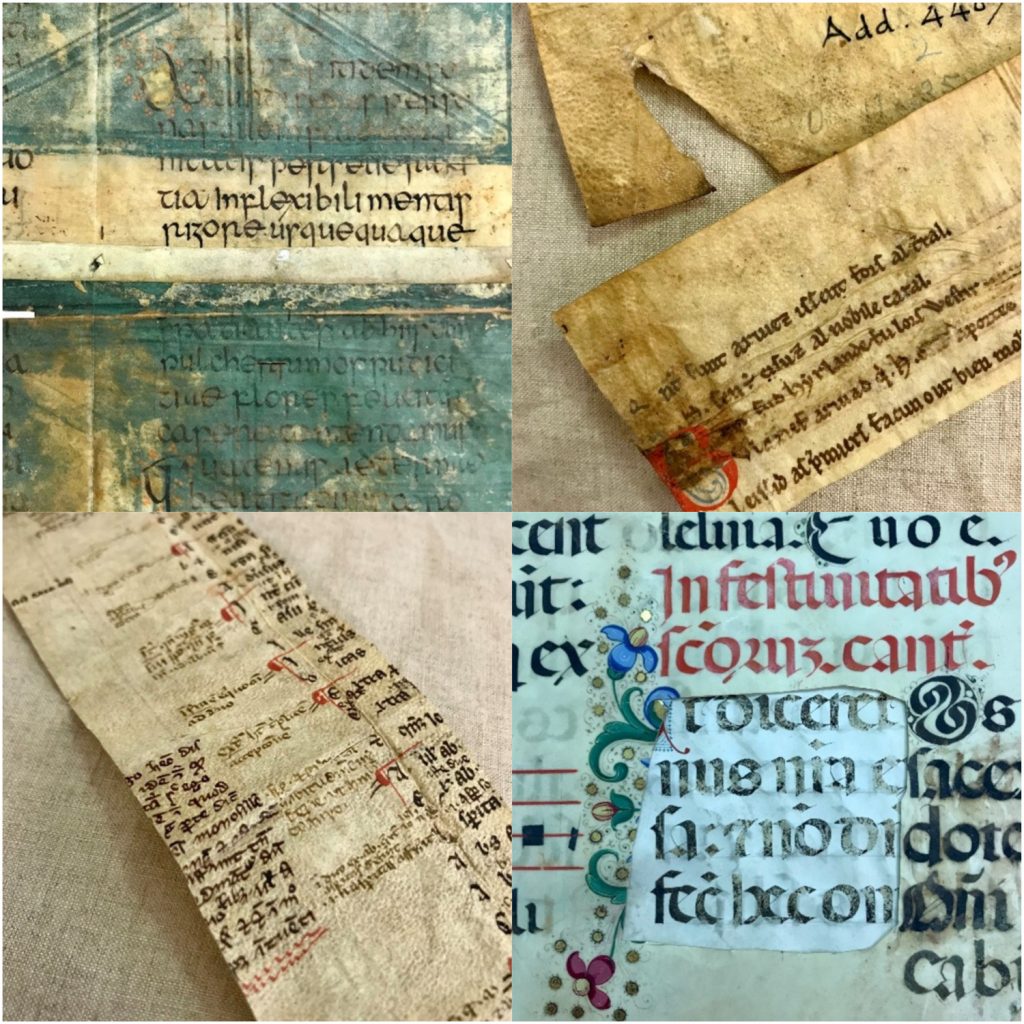

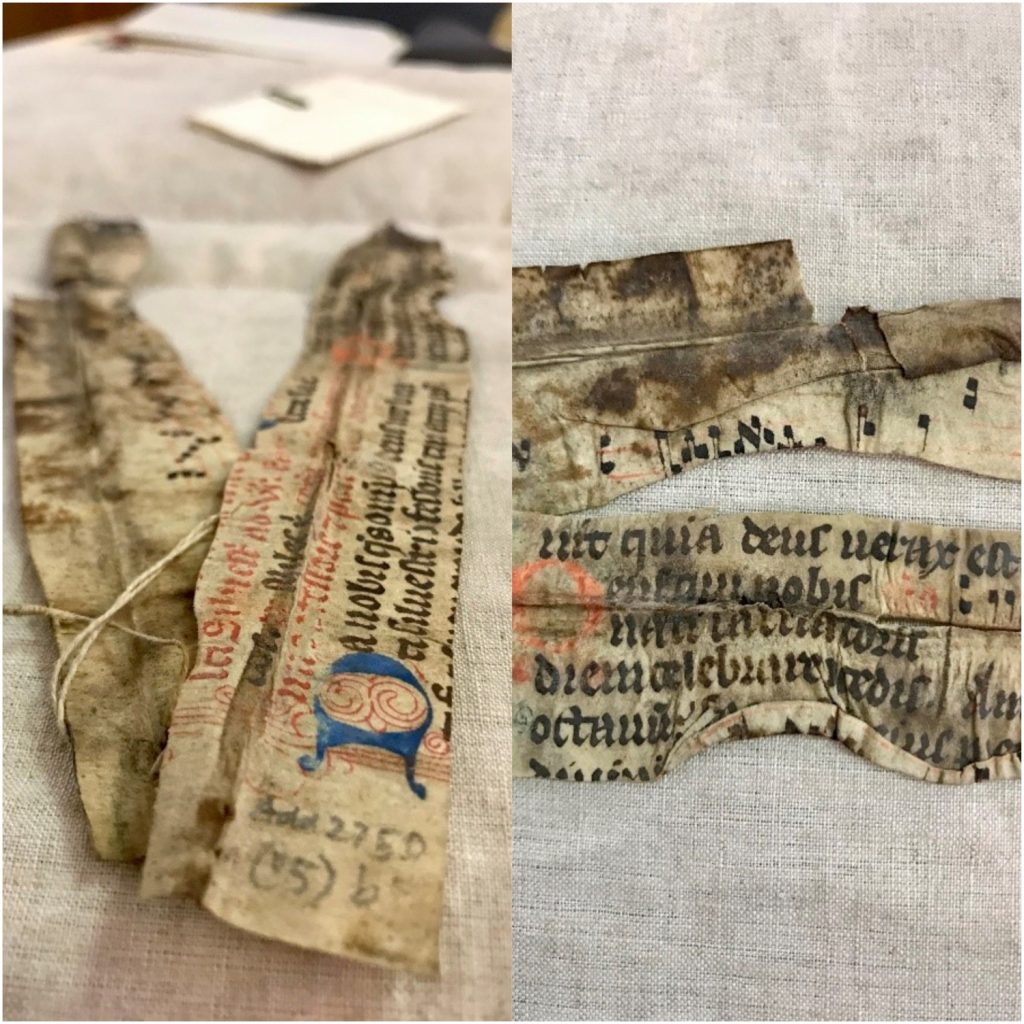

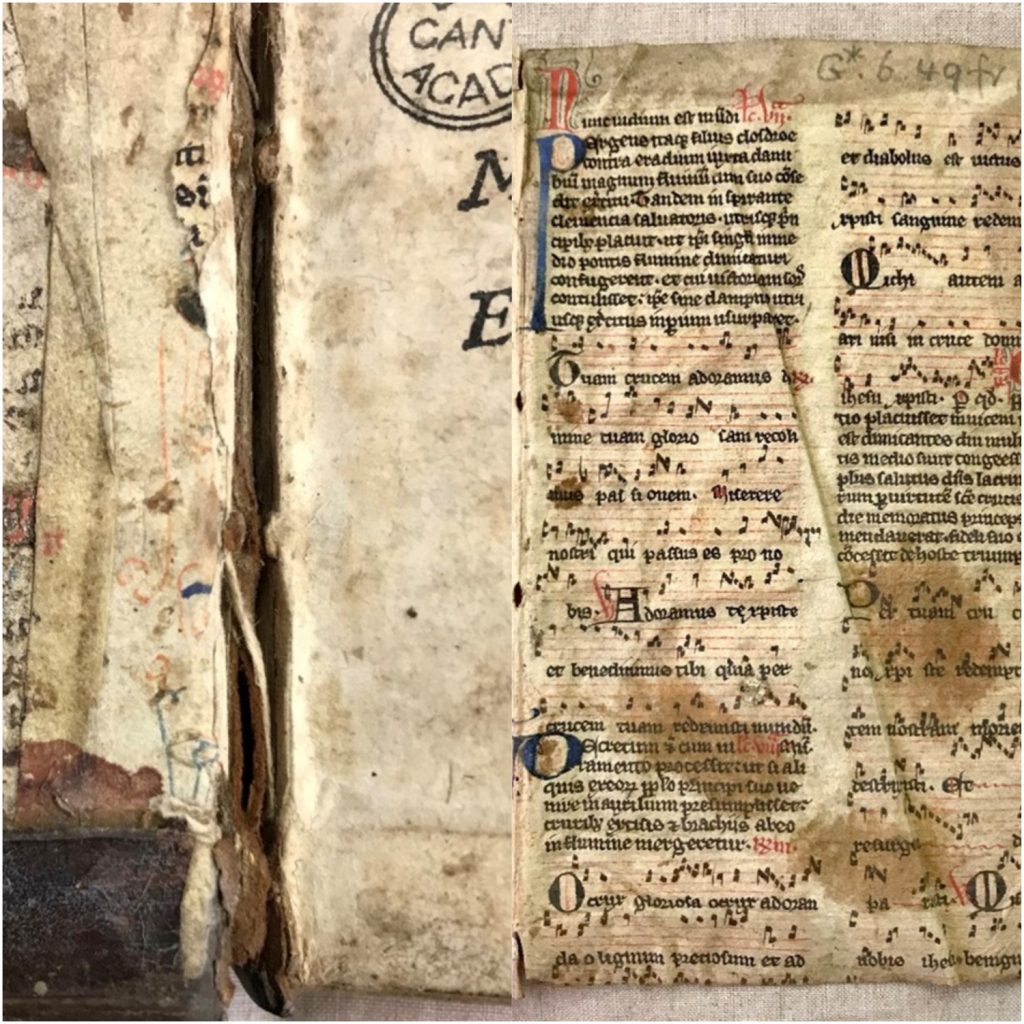

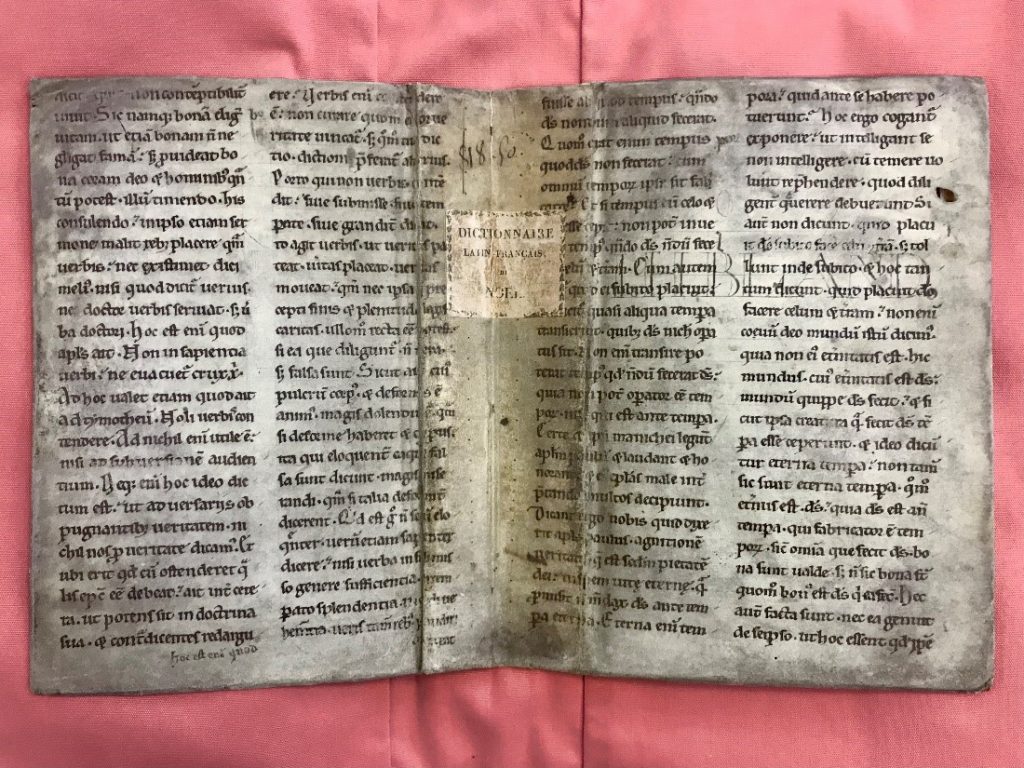

A square of parchment no larger than a postage stamp, bearing a scattering of words from a Middle English hagiographical work. Two skinny strips from a 12th-century copy of Augustine’s sermons. A single quire from a book of hours. Dozens of miscellaneous fragments held together with paperclips and crammed into an early-20th century portfolio. These are just a few of the rag-and-bone treasures that come across my desk as the UL’s new Fragmentarium Research Associate. Sponsored by the University of Fribourg-based Fragmentarium initiative and funded by the Zeno Karl Schindler Foundation, our project aims to complete the cataloguing, conservation, and digitisation of a significant selection of the more than 2200 known fragments within the UL’s Additional manuscripts class. The images and descriptions we produce will be published on the Cambridge University Digital Library (CUDL), and some may join the database on Fragmentarium.ms, the premier online hub for fragment studies.

On paper, my role as cataloguer is to identify, describe, and encode the fragments, making their form and contents both human- and machine-readable, often for the first time. In practice, however, it often feels more like foraging in the attic of the library, emerging with piles of half- or un-processed materials, some of them accompanied by notes and other ephemera in the hands of long-dead librarians. For me, it is work that exists at an ideal intersection of cataloguing, research, and library history. Let me tell you about it.

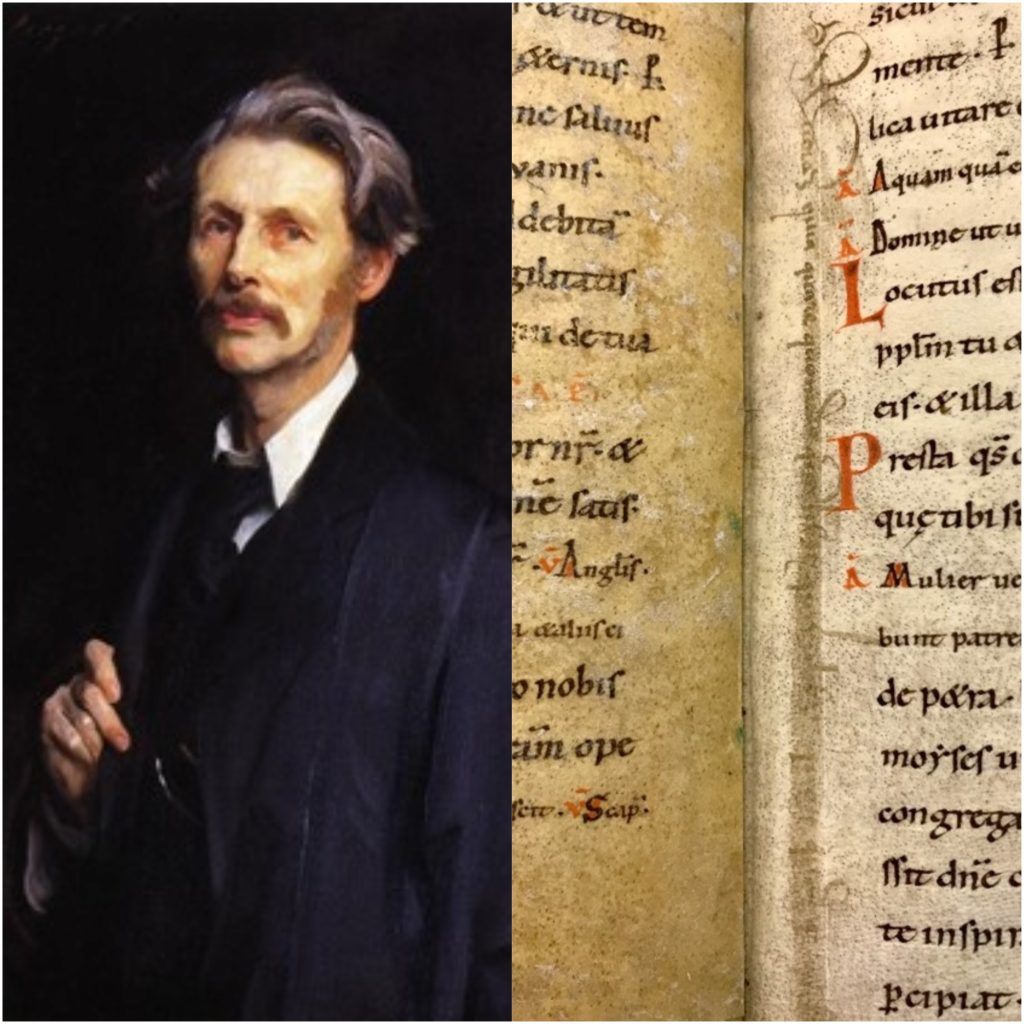

First, a bit of background. The UL holds more than 80 collections of Western medieval manuscript fragments within the Additionals sequence, comprising at least 2250 individual items, not including those still in situ in early printed books or other manuscripts. The material, textual, and linguistic scope of this ‘collection of collections’ as our Manuscripts Specialist Dr James Freeman calls it, is known only in broad strokes via a series of unpublished descriptions written by several 20th-century curators, and a brief handlist compiled by Jayne Ringrose while researching her Summary Catalogue of the Additional Medieval Manuscripts in Cambridge University Library acquired before 1940 (2009), a volume which in fact deliberately excludes the fragment collections. As part of the history of acquisition here at the UL, the Additional classmark sequence was created in the middle of the 19th century to designate new manuscripts being added to the collection. And indeed, many of the fragments in our project did arrive in Cambridge in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, bequeathed by various personalities including Librarian Francis Jenkinson, whose interest in ephemera and what we might today call “fragmentology” is well-documented.

However, the vast majority of the Additional fragments had already been in the library for centuries at the time of their so-called acquisition, waiting patiently in the bindings of other codices to be removed and given their own classmark – in other words to be formally recognised as significant holdings in their own right. And herein lies the first lesson of this ‘collection of collections’: they are always greater than they appear on the surface, both compelling as medieval survivals, and deeply tied to the early history of manuscript curation and cataloguing in Cambridge.

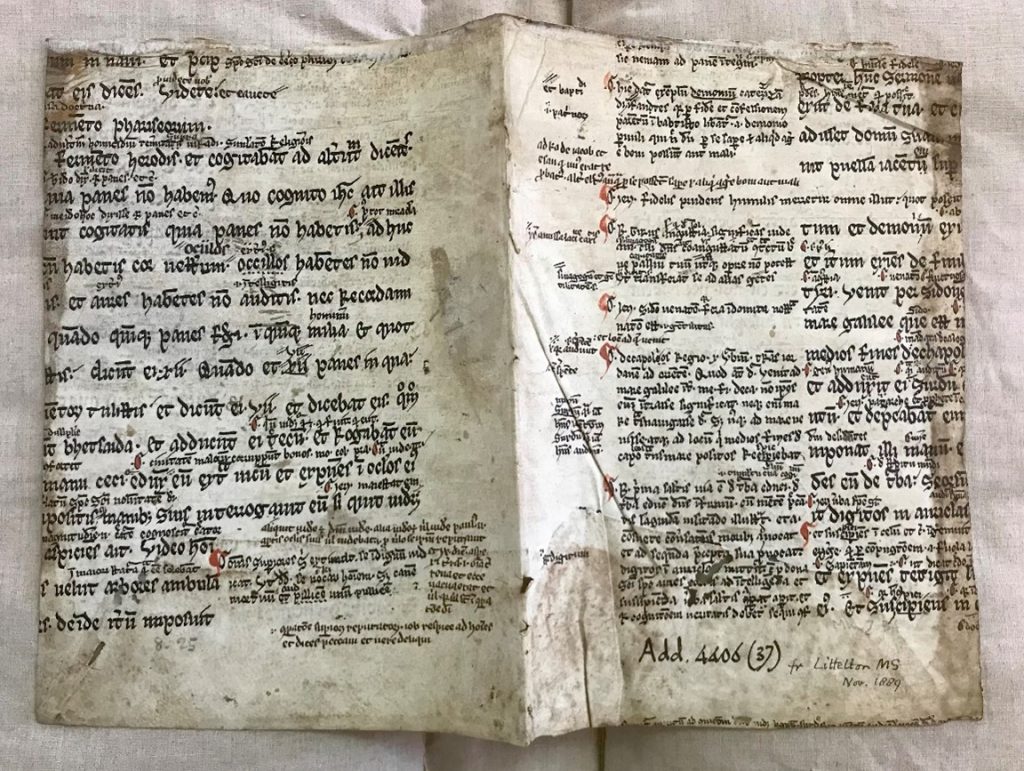

This unique institutional history, combined with the scarcity of readily available information on their content and provenance, means that the Additional fragments represent a fundamentally understudied reservoir of Western medieval material culture that has yet to see sustained scholarly attention. Moreover, the decentralised nature of the collections’ organisation means that from my perspective as a cataloguer, every box is a kind of lucky dip of form and genre, and I’m never certain whether the next item is going to be a fragment from a vernacular romance (my former academic speciality) or somehow another glossed copy of Gregory’s decretals (with apologies to any canon law fans). When I discuss this project with colleagues and friends, the first question I get is invariably the same: do you think you’ll discover an unknown text? While it is true that some individual fragments are uniquely valuable in and of themselves – Add. 4406 (39), for instance, is a previously unknown witness to the Carolingian Homiliary of Saint-Père de Chartres, a rare sermon collection well known in late Anglo-Saxon England – the vast majority are relatively common survivals ranging from legal and philosophical texts to liturgical works.

But ‘common’, of course, is relative. Recently, I was slogging through a box of previously undescribed liturgical fragments, frankly bored by the seemingly endless parade of near-identical hymns and square notation, when a musicologist stopped by (these things happen when you work in Cambridge). I spent the next two hours utterly enraptured by his joyful elucidation of the smallest scraps of medieval plainsong; I learned more about identifying and localising liturgical manuscripts in one afternoon than I had in years of cataloguing. Herein the second lesson: fragments are invaluable teaching tools, allowing students to engage with manageable objects that require them to focus on details rather than being overwhelmed by the entirety of a medieval codex. They also provide fruitful opportunities for the practice of skills like palaeography, codicology, and even cataloguing: two doctoral students are currently working with me on the project, and we are hoping to run at least one workshop or transcribe-a-thon aimed at graduate students in the humanities.

Beyond their specific contents and (inter)disciplinary relevance, the Additional fragments also speak to us at scale, both as a significant repository of information about the use and reuse of medieval manuscripts in the post-medieval era, and as a collection that gestures toward larger questions of how we as librarians and researchers understand fragments, their role and significance within our collections. For myself, one of the most exciting aspects of working with fragments is the ways in which they ask us to reconsider key concepts and long-held terminologies. For example, the use of manuscript fragments as “binding waste” in early printed books has long been used to undo the notion of a distinct print culture, but what happens when we stop thinking in terms of “waste” at all? A quick glance at that old standby the Oxford English Dictionary tells us that our word waste derives from the Old French wast meaning unoccupied or uncultivated, as of land. Such a definition is anathema to the very nature of our manuscript fragments – far from a cultural wasteland, these objects provide fertile ground for us to reimagine how we usually understand, catalogue, and present medieval materials.

Moreover, when viewed in the right light, fragments fundamentally explode the idea of discrete collections, and ask us to think widely and cooperatively about manuscript survivals. Lisa Fagin Davis, the noted fragmentologist and longtime collaborator of the Fragmentarium initiative, is famously working with dozens of repositories and private owners to virtually reconstruct the Beauvais missal, a 13th-century French manuscript originally broken by New York book dealer Philip Duschnes in the 1940s and disseminated by the biblioclast Otto Ege via his “Fifty Original Leaves of Medieval Manuscripts” portfolio. The question “who owns the Beauvais missal?” is therefore rhetorical ad absurdam, and demonstrates one small way in which fragments call upon us to move beyond current institutional models – inherently siloed and possessive – toward more collaborative approaches to our global cultural heritage. In practice, this means cataloguing becomes a balancing act, at all times recognising any given fragment as part of a once-complete manuscript while simultaneously acknowledging it as whole in itself, a ‘complete fragment.’ This paradox is for me the third lesson: working with fragments requires a concerted effort to view each of its lives and identities as distinct yet united, like looking through a prism.

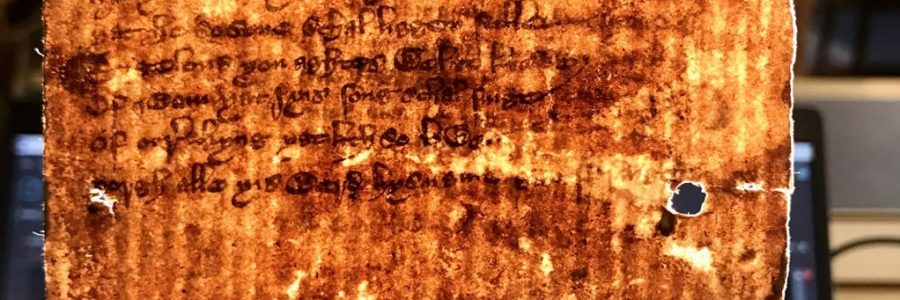

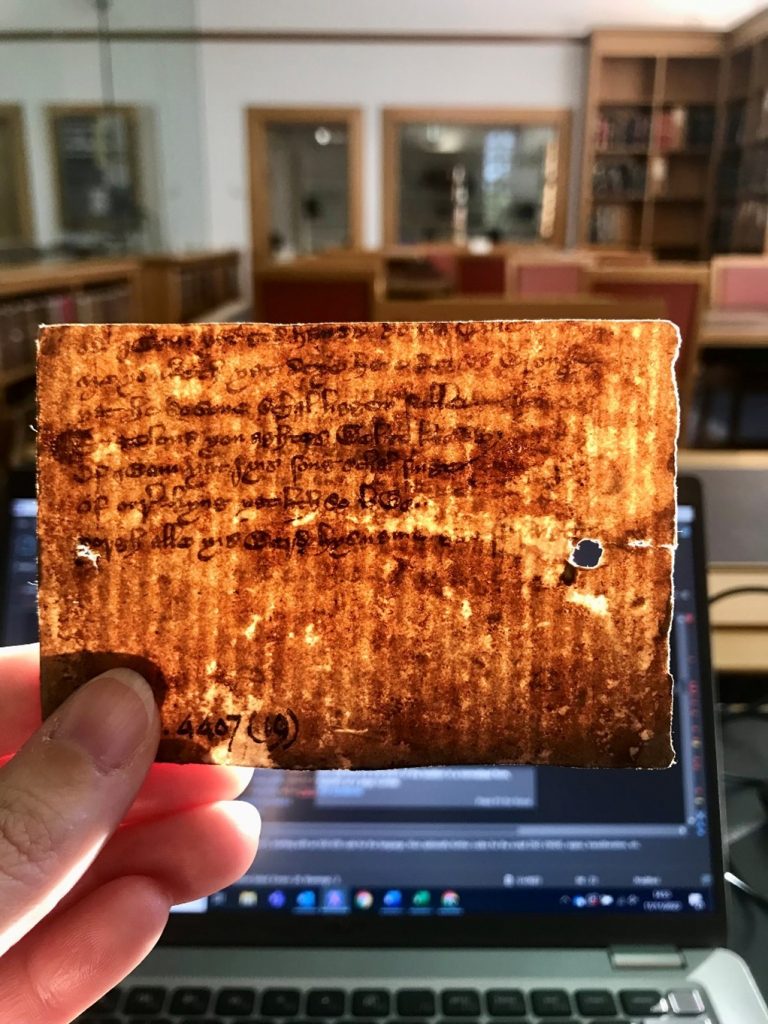

For those of you interested in the cataloguing nitty-gritty (metadata nerds unite!), MS Add. 4407 (12), a partial leaf from the documentary compilation known as the Coucher Book of Furness Abbey makes a nice example. Likely produced at Furness itself, the majority of the original manuscript is now in two pieces, held at both The National Archives and the British Library, while the UL fragment was apparently removed from a printed book in the collections, as per unpublished notes by mid-20th-century under-librarian Basil Atkinson.

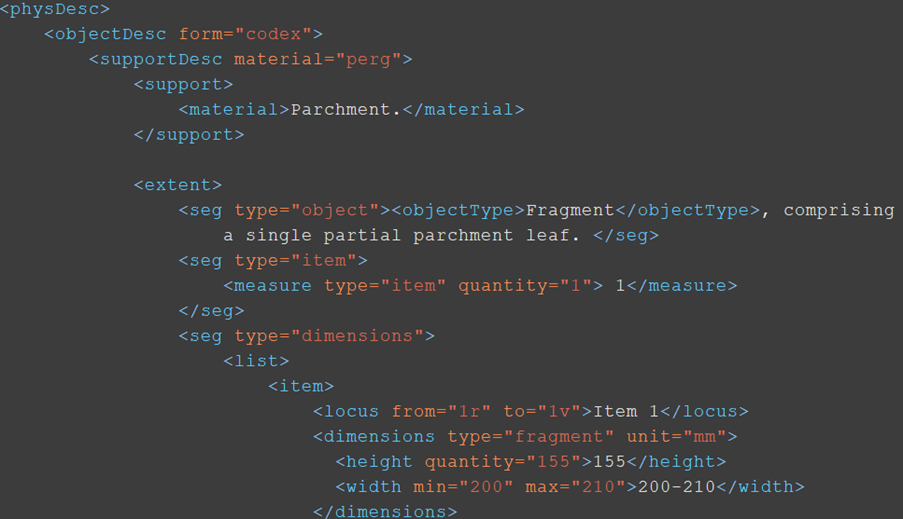

When cataloguing in TEI, the <physDesc> element contains all relevant information about the form of the object, including its extent, layout, and dimensions. If we look at the opening portion of the <physDesc> for MS Add. 4407 (12), the typical fragmentological contradiction jumps right out at us:

Within the <objectDesc> tag, we can see that ‘form=”codex”’ while under <extent> we see clearly ‘type=”object”’ with the <objectType> designated as ‘Fragment.’ This is the dual identity of the fragment made machine-readable: because the leaf was once part of a codex, <objectDesc> reflects this previous identity, theoretically reuniting the fragment with the rest of its parent manuscript. But of course MS Add. 4407 (12) is not a codex, and the <extent> and <objectType> tags below reflect this, describing not an idealised complete Coucher Book of the past, but the current object whose fragmentary dimensions are listed below. Furthermore, since the other portions of the original manuscript are in known locations and have been recorded in G.R.C. Davis’ Medieval Cartularies of Great Britain and Ireland, revised by Claire Breay, Julian Harrison & David M. Smith (2010), information beyond the scope of the UL fragment itself can be added to the record, including the dimensions of a complete leaf, a precise date (1412), and even the name of the scribe (John Stell). Finally, in putting our images of the Coucher Book up online via CUDL, including IIIF capabilities, we look toward the future imagined by fragmentology whereby the boundaries between collections and repositories are broken down, and the work of curators, cataloguers, conservators, and digitisation specialists from across the globe may be united virtually.

There’s so much more to say about the UL Additional fragments and how they can reshape our understanding of manuscript collection, curation, and cataloguing – indeed, I’ve barely even scratched the surface here! I do hope I have at least whetted your appetite for all things fragmentary, so please do keep an eye on this blog for more on our progress and findings.

Dr Marie Turner, Fragmentarium Research Associate

Absolutely fascinating. On with the good work. I look forward to seeing further updates.

Congratulations on this fantastic project!

Will you be examing fragments at individual Cambridge colleges as well, or is this specific to the main University library?

Many thanks, Mark. This project is focused on fragments in the main University Library collection but we know that there are a lot of fragments out there in the colleges too. The same methodology could be applied in the college libraries and we will be talking to college librarians about the project.

Fascinating and complicated work, well explained.