A game of stones – how Cambridge acquired a cast of the Rosetta Stone

Exactly two hundred years ago, in 1822, the French scholar Jean-Francois Champollion (1790–1832) succeeded in his attempts to decipher the hieroglyphic text of the famous Rosetta Stone. This anniversary is being widely commemorated in talks and exhibitions around the world including the current ‘Hieroglyphs: unlocking ancient Egypt’ exhibition at the British Museum in London where the Stone has been housed since 1802.

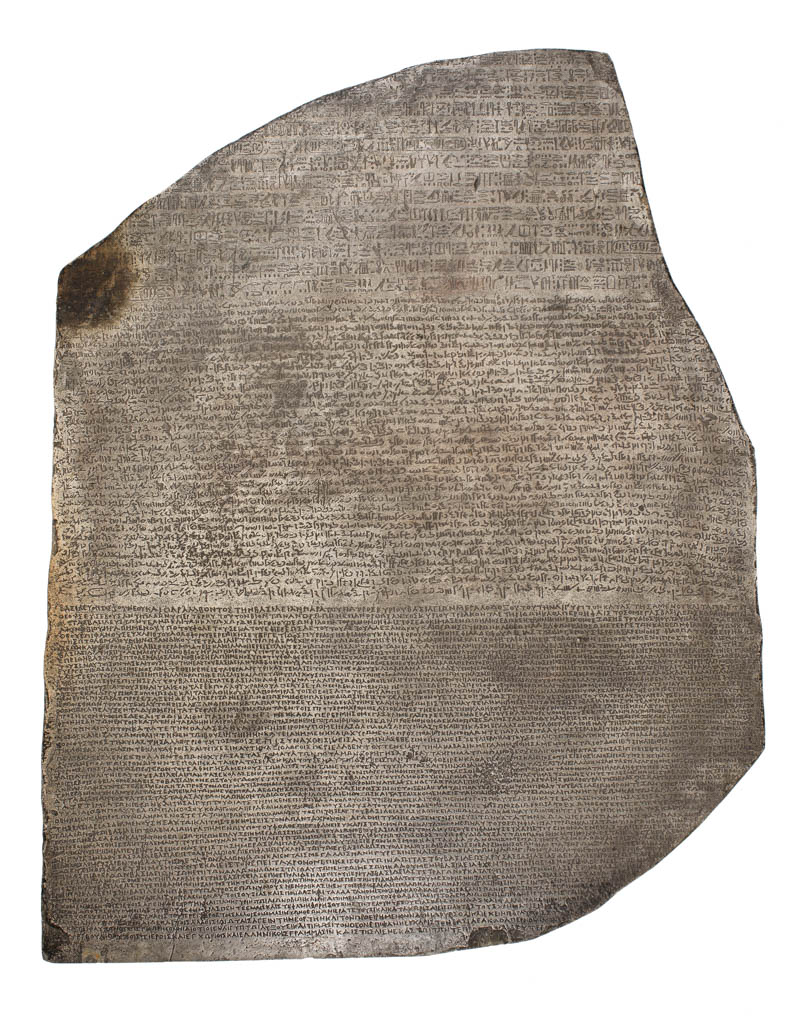

The ancient stone stele with a decree written in hieroglyphs, demotic and ancient Greek, evaded all attempts at decipherment for many centuries. Napoleon’s military campaign in Egypt in 1798–1801 brought about its discovery by Europeans – it was found by a French soldier in July 1799 close to in the port of Rosetta (Rašīd). It was appropriated and added to a collection of other antiquities made by the ‘savants’ or ‘scavans’, the scholars who accompanied Napoleon’s army. The Stone was sent to Cairo, where the significance of the texts was immediately recognised. Several impressions of it were taken and sent to Paris, and then in April 1801 it was transported to Alexandria and stored in the house of General Menou, commander of the French forces.

In the Spring of 1801, after the French army in Egypt was defeated by the British at the Battle of Alexandria, a peace agreement was signed that included a clause stating that the antiquities held by the French must be surrendered to the commander of the British forces, General Hutchinson. This caused an outcry from the French.

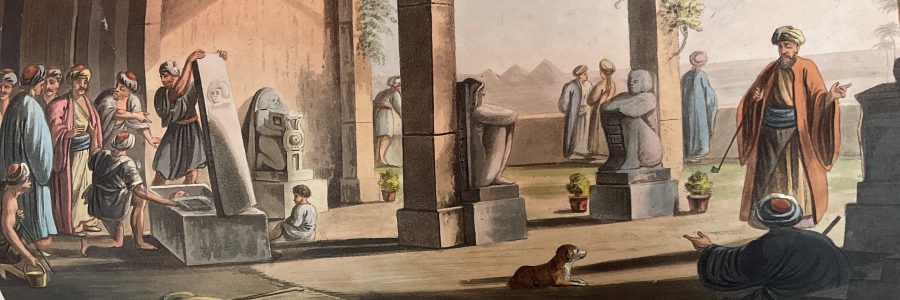

From Views in Egypt —in the possession of Sir Robert Ainslie by Luigi Mayer. 1801.

Even then the ownership of the Rosetta Stone was disputed and its handover was consequently fraught with difficulties. General Menou had come to regard it as his own private property, but Lord Elgin, the British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, who was based in Constantinople, had sent his own personal secretary, William Richard Hamilton (1777-1822) to Egypt with a special assignment to settle the peace negotiations and mastermind the handover of all the antiquities.

A lively eye-witness account of the whole controversy was provided by the Cambridge traveller and collector Edward Daniel Clarke (1769–1822), who was in Egypt at the same time. He was reaching the end of a three-year long expedition across Scandinavia, Russia, Crimea, Greece and the Holy Land. In 1801 Clarke had arrived in Alexandria and met up with Hamilton, continuing a friendship formed in Constantinople earlier in his expedition. Clarke became closely involved in the controversy of the transfer of all the collections from French to British hands and obtained a pass so he could gain access to the encampment where the Stone and other antiquities were kept.

In a letter written to his friend (and later biographer), William Otter, on September 14th 1801, Clarke, then in Alexandria, gave a full description of the heated dispute between the British and French generals and the part he himself played in this. Clarke reports:

‘a great dispute has arisen between Generals Hutchinson and Menou about the antiquities and collections of Natural History made by the corps of ‘scavans’.

Also, in the process of attempting to transfer the Stone itself:

‘Menou has threatened him [Hutchinson] with all the effects of his fury; says he will publish him as a thief to all Europe, and finally that he will fight him on his return’.

In the same letter Clarke continued to state that not only did he manage the successful transfer of the Stone to British hands but that he had also attempted to obtain it for Cambridge in particular:

‘I was in Cairo when the capitulation began. There I learned from the Imperial Consul, that the famous inscription which is to explain the Hieroglyphics, was still in Alexandria. I then intended to write to General Hutchinson and Lord Keith on that subject, to beg it might be obtained for the University of Cambridge or the British Museum…’

Eventually Hutchinson sent Clarke to Menou to find out more about the ownership of the antiquities. After heated discussions with the savants, who had threatened to destroy all the artefacts, Hamilton rewrote the settlement so that the natural history specimens were to remain with the French but the antiquities, including the Stone, were to be handed over to the British. Clarke played a significant part in the negotiations. In the volumes of his travels, published subsequently, he gives a detailed account of these events.

All accounts of the handover of the Stone vary in detail, but it appears that Hutchinson instructed Hamilton and Clarke to recover it. Later, Hutchinson’s aide, Colonel Hilgrove Turner of the Guards along with a detachment of soldiers took possession of it from Menou’s residence in Alexandria and embarked with it on a captured French vessel H.M.S. “L’Égyptienne,” docking at Portsmouth in February 1802. Subsequently the Stone was shipped to Deptford and on March 11, deposited at the Society of Antiquaries of London of which Turner was a Fellow. In July the President of the Society ordered four plaster casts of the Stone to be made for the Universities of Oxford, Cambridge, Edinburgh and Dublin so that it could be studied widely. Towards the close of 1802, the Stone was moved from the Society of Antiquaries to the British Museum, where it was exhibited to the general public.

It is recorded that it was Clarke who gave the cast of the Stone made for Cambridge to the University Library where it was displayed in the Entrance Hall. In the ‘Guide to the University of Cambridge’ published in 1803 it is recorded that:

‘Near the entrance into the East Room is found a beautiful facsimile, in plaster of Paris, of the remarkable triple Inscription found at Rosetta: the possession of which general Menou so warmly contested with the Commander in chief of the British forces; and which was delivered by the French to Mr Clarke of Jesus College at Alexandria, previous to the evacuation of that city by order of Lord Hutchinson’.

It remained on display during 1817–1822, when Clarke was himself University Librarian, and was still apparently on view in 1825. In Charles Sayle’s Annals of Cambridge University Library published in 1916, he stated that in May 1865, the several Greek marbles donated to Cambridge by Clarke were removed to the Fitzwilliam Museum, but no mention is made of the Rosetta Stone cast.

The archives of the Fitzwilliam Museum record that the donation of the cast there was made in 1855 by ‘Sir G. Scarf’; possibly this is Sir George Scharf, the artist and fellow of the Society of Antiquaries. Scharf, an artist and lithographer was born in London in 1820. He developed an interest in ancient civilization, travelled abroad as an official artist and published drawings of antiquities. He became a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in 1852 and was very active in the museum world, becoming in 1856 secretary of the newly established National Portrait Gallery. Scharf was on visiting terms with Cambridge figures such as John Willis Clark, and he attended the opening ceremony of the Museum of Classical Archaeology in 1884. Since he was such a prominent figure in Cambridge’s own museum world at the time the cast was transferred to the Fitzwilliam, it is very plausible that he was involved.

Clarke’s involvement in the acquisition of the Rosetta Stone for the British was probably significant, but his attempt to claim it for Cambridge had failed, perhaps because his visit to Egypt was only brief and he was out-manoeuvred by more powerful figures. Nevertheless, that his travels coincided with the crucial period of its transfer from French to British hands and that he left eye-witness accounts of the events adds colourful detail to this complex story. Clarke returned to Cambridge and became a Fellow of Jesus College. The Cambridge cast of the Rosetta Stone is held in the Fitzwilliam Museum’s collections to this day.

Stela cast: E.1.1855 https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/object/49047

Bibliography

Clarke, E.D., Travels in various countries of Europe, Asia and Africa. Part 2 (2). 4th ed. Vol. 5. London, 1817

Otter, W., The life and remains of Edward Daniel Clarke. New York, 1827

Parkinson, R. The Rosetta Stone. London, 2005

Sole, R.., Valbelle, D. and Davis, W.V. The Rosetta Stone. London, 2006

Usick, P., The discovery of the Rosetta Stone In Hieroglyphs: unlocking ancient Egypt, ed. I. Regulski. London, 2022