Joyful Sounds of Salvation

The Library Choir has been performing carols in the University Library Entrance Hall for more than thirty years. This year each of the seven carols we are singing comes from a different European country, from England to Ukraine. Most of them are taken from a collection called The University Carol Book (1961), edited by the Congregationalist minister and musician Erik Routley. You can read more about his anthology here.

By the time Routley’s book appeared, collections of Christmas carols had been appearing in print for four and a half centuries. I looked at some of them in a post three years ago. Up until the nineteenth century, carols circulated in the popular repertoire in the form of broadsides and chapbooks. Two chapbooks (small booklets usually made from a single sheet of paper folded to make eight leaves) from the UL’s collections featured in my earlier post, but at that time I thought that we didn’t possess any carol broadsides. The following summer, however, my colleague Liam Sims found this rather ragged example in a drawer.

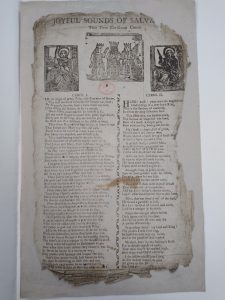

Joyful Sounds of Salvation, printed by Joshua Davenport of Clerkenwell around 1800 (Broadsides.B.80.8)

A broadside is, like a chapbook, a publication on a single sheet of paper, but this time it is unfolded and printed on one side of the paper only. We can imagine it held or pinned up for a group of people to read or, in this case, sing from. Like chapbooks they are rarely if ever dated; all we know about this example is that it was printed by Joshua Davenport of Clerkenwell, a ballad printer who was active between 1790 and 1808. His wares would have been sold in the street by hawkers. In 1836 the Scottish journalist and author Thomas Kibble Hervey wrote of these:

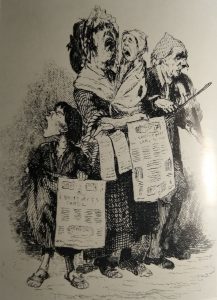

‘Our readers are no doubt aware that the carol-sheets still make their annual appearance at this season, not only in the metropolis, but also in Manchester, Birmingham, and perhaps other towns. In London they pass into the hands of hawkers, who wander about our streets and suburbs enforcing the sale thereof by—in addition to the irresistible attraction of the wood-cuts with which they are embellished—the further recommendation of their own versions and variations of the original tunes, yelled out in tones which could not be heard without alarm by any animals throughout the entire range of Nature, except the domesticated ones, who are “broken” to it. For ourselves, we confess that we are not thoroughly broken yet, and experience very uneasy sensations at the approach of one of these alarming choirs.’ (The Book of Christmas, p. 215)

Our broadside contains two carols. “In the reign of great Caesar” is one of the family of carols related to “A Virgin Most Pure”, still sung by choirs today. It was reprinted in the 1860s by W.H. Husk and in the 1920s by R.R. Terry under the title “Joyful Sounds of Salvation”, which is here used as the title of the broadside. “Hark, hark, what news the angels bring” must have been popular in its day, judging by the frequency with which it appears in early publications, and survived in the folk repertory into the twentieth century. It first appeared in Church Harmony Sacred to Devotion (1757) by Joseph Stephenson of Poole (1723-1810) and was probably composed and perhaps also written by him.

Song sheets were often ornamented with crude woodcuts which may or may not have been relevant to the subject of the song. Our example has two Evangelists and the three Kings following their star. They are primitive by the standards of the day, but seem to have been in accord with popular taste. The radical pamphleteer William Hone, an early enthusiast for carol broadsides, wrote of some other examples:

‘The attachment of Carol buyers extends even to the wood cuts by which they are surrounded. Some of these, on a sheet of Christmas Carols, in 1820, were so rude in execution, that I requested the publisher, Mr. T. Batchelar, of 115, Long Alley, Moorfields, to sell me the original blocks. I was a little surprised by his telling me that he was afraid it would be impossible to get any of the same kind cut again, When I proffered to get much better engraved, and give them to him in exchange for his old ones, he said, ‘Yes, but better are not so good; I can get better myself: now these are old favourites, and better cuts will not please my customers so well.’ (Ancient Mysteries Described (1823), p. 100).