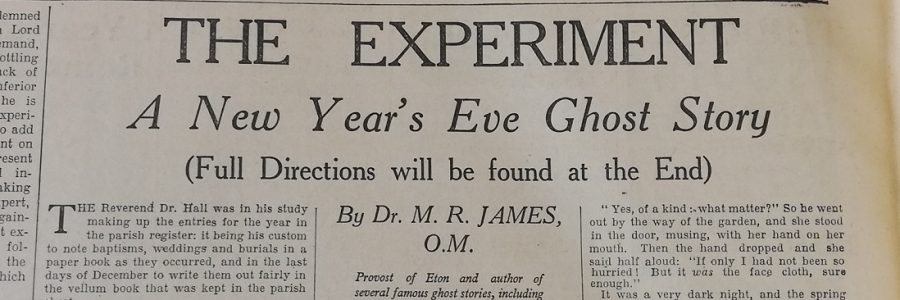

A New Year’s Eve Ghost Story

This Christmas we bring you a spine-chilling ritual for conjuring spirits from the margins of a medieval manuscript that features in our current Curious Cures in Cambridge Libraries project. However, the ritual’s greatest claim to fame is that it stars in one of the final ghost stories written by the well-known manuscript scholar and horror writer Montague Rhodes James (1862–1936): The Experiment.

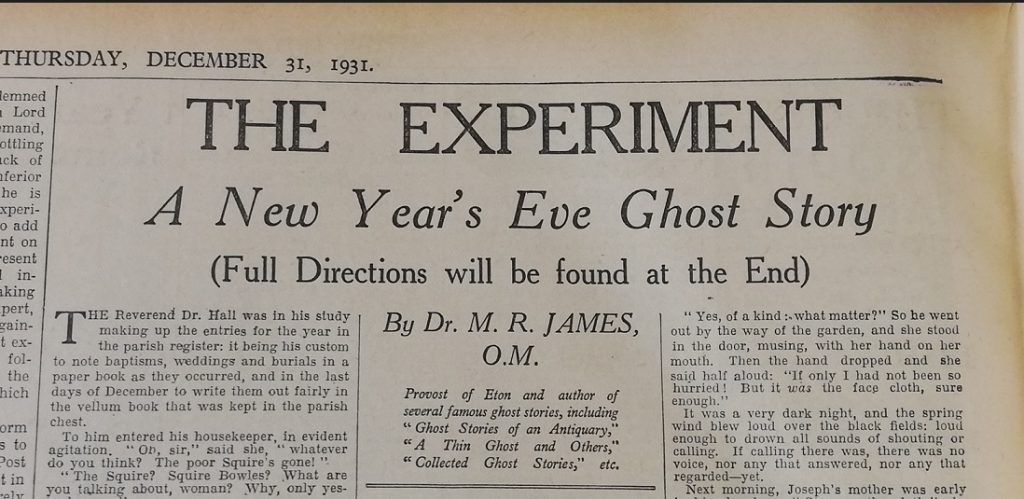

James wrote The Experiment in 1931 just after the publication of the omnibus of his ghost stories that very same year. James typically wrote his stories for Christmastime when he would read them aloud to his Cambridge friends, but in 1931 he was running late and finished his story only just in time for inclusion in the 31 December edition of the London newspaper The Morning Post with the apt sub-title ‘A New Year’s Eve Ghost Story’.

Medieval manuscripts inspired many of the extraordinary ghost stories that M.R. James is best known for today. Between the 1890s and 1930s, he published over thirty such stories while also producing detailed descriptions of hundreds of medieval manuscripts in Cambridge’s colleges and the University Library. Although his work as a cataloguer evidently inspired stories such as Canon Alberic’s Scrap-Book, its influence is nowhere as clearly visible as in The Experiment.

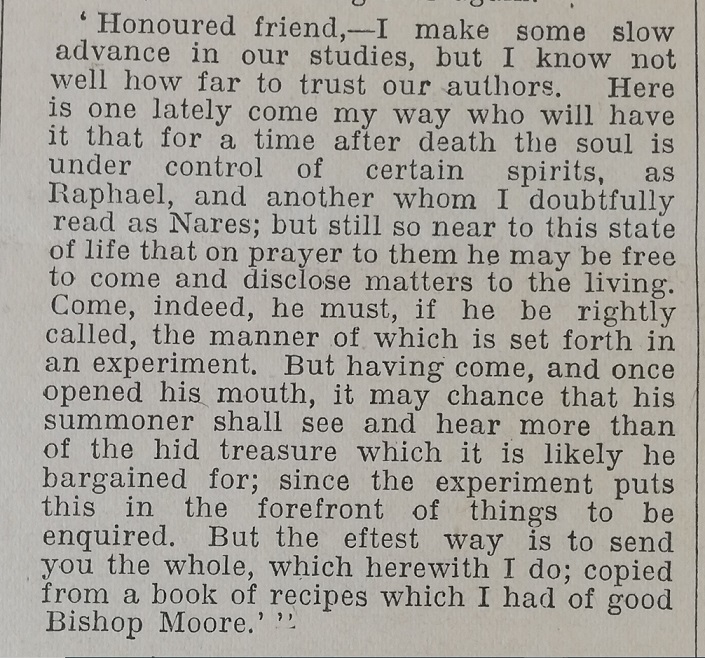

The story tells of the fate of Joseph Calvert and his mother ‘Madam Bowles’ after their stepfather and second husband Squire Francis Bowles dies under mysterious circumstances. Although the latter was a wealthy landowner in life, his sole heirs, mother and son, cannot find a trace of his money. While searching for clues in his stepfather’s papers, Joseph discovers an unsent letter in which the Squire describes an experiment from a medieval manuscript that had been sent to him by John Moore (1646–1714), Bishop of Norwich. The experiment describes a ritual through which one can communicate with the soul of a dead individual. Hoping to learn about the whereabouts of the Squire’s treasure, Joseph follows the ritual and summons his stepfather’s soul. But the decomposing face that meets him terrifies him too much to learn anything useful from the vision. Feeling haunted, both he and his mother sail from England to ‘Holland’. But they are followed by an ominous hooded figure. There is clearly no escape from the invoked spectre of the Squire. Records from Norwich, James concludes, suggest that mother and son eventually returned to England and, after confessing to having murdered Squire Bowles by poisoning, were executed for their crime.

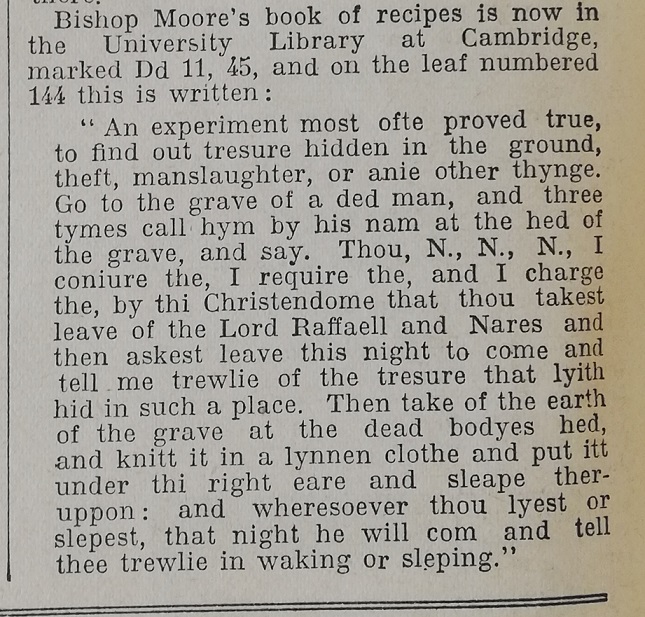

At the end of The Experiment, James reveals that the medieval manuscript from which the Squire copied the ritual now has the classmark Cambridge, University Library, MS Dd.11.45 and gives a complete transcription of the text. According to James’s rendition, the experiment can be used to discover treasure in the ground, the identity of a thief, a murderer, or any other thing. To follow it, you need to go to a dead person’s grave, call their name three times, and command them to ask permission from two angels called ‘Raffaell’ and ‘Nares’ to come to you that night and answer your questions. Subsequently, you need to take earth from their grave and wrap it in a cloth and place it under your pillow before you go to bed. The soul of the dead person, as the text assures, will then visit you that night either while you are asleep or awake.

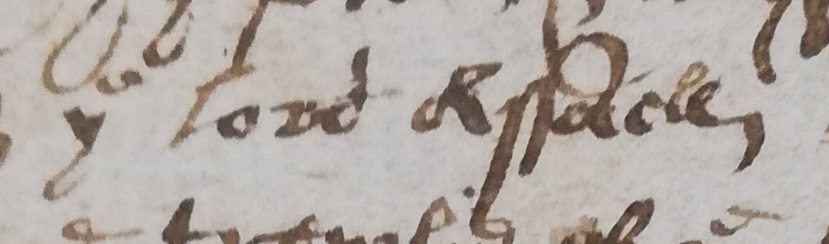

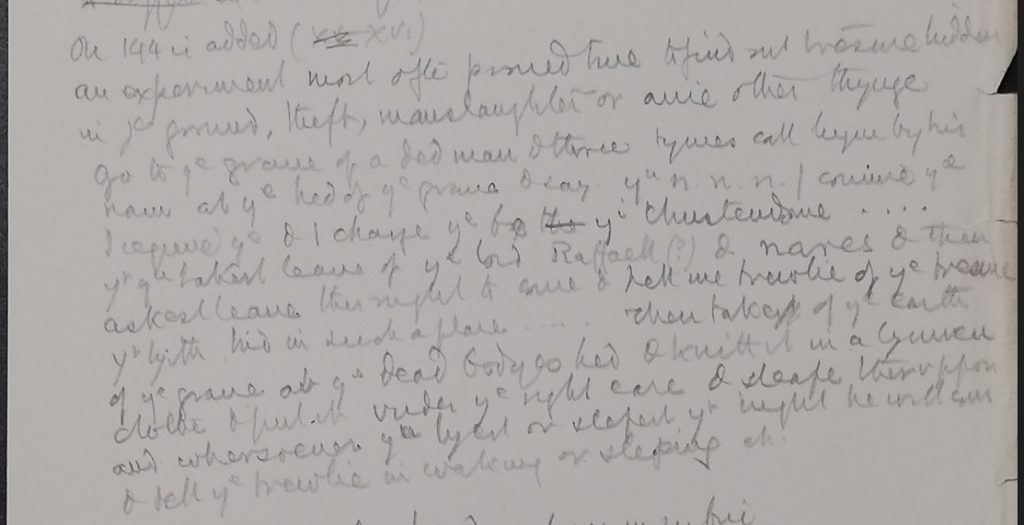

Turning to the medieval manuscript that James relied on (Dd.11.45), we find the ritual added by a sixteenth-century hand to the empty lower margin of a fifteenth-century collection of medical recipes in Middle English and Latin. A comparison between the manuscript and James’s transcription shows that he has omitted a few lines but closely followed the manuscript otherwise.

However, a minor but significant error has crept into his version that so far has gone unnoticed. While James transcribes the name of the first spirit as ‘Raffaell’, presumably meaning the Archangel Raphael, the manuscript, in fact, reads ‘Assaell’. This changes the nature of the ritual from an angelic to a demonic one. ‘Assaell’ almost certainly is the fallen angel Azazel who, according to the biblical book of Enoch, led mankind into wickedness by teaching it about making weaponry, jewellery, cosmetics, and the practice of witchcraft, until he was captured and imprisoned by the Archangel Raphael.

James appears to have been doubtful about his transcription of the spirit’s name as well. In his handwritten description of manuscript Dd.11.45, unpublished and kept at the University Library, he has added a question mark next to the name ‘Raffaell’. Despite his uncertainty over the accuracy of his transcription, he was unable to check the manuscript again while working on The Experiment. Not only was he working under severe time-constraint, but the University Library would also have been closed for Christmastime!

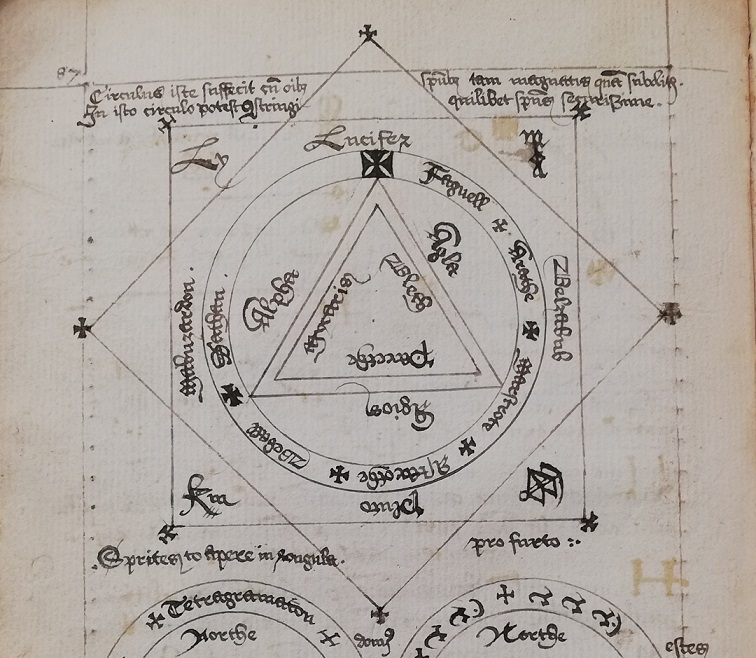

James’s misidentification of the spirit may have prevented modern scholars from identifying the text in Dd.11.45 as a copy of a widely disseminated magical work on the practice of communicating with the spirits of the dead—also known as necromancy. Our copy, for example, is not listed in a 2019 article by Daniel Harms (‘“Thou Art Keeper of Man and Woman’s Bones” – Rituals of Necromancy in Early Modern England’, Thanatos, 8:1 (2019), 62-90) in which he identifies the very same ritual in no less than fifteen fifteenth- and sixteenth-century English collections of magical texts. Importantly, Harms notes that despite variations between these copies they all agree that the spirit’s name is Azazel who, in some cases, is referred to as the ‘King of the dead’ and ‘Keeper of the bones of the dead’. In some versions, one does not only need to conjure the soul of the dead but also Azazel directly in order to obtain his help with the ritual. This only confirms that the necromantic instruction in Dd.11.45 belongs to a type of dark magic in which sorcerers go as far as to invoke demons or the devil himself to achieve their aims.

Our correction of M.R. James’s transcription does not detract from his scholarly work. Curious Cures in Cambridge Libraries builds on many of James’s (un)published manuscript descriptions today. We are lucky to have new resources and techniques at our disposal with which we can regularly make additions and corrections to older catalogue records. Please keep an eye on this blog for posts on findings from our project in 2023!

We wish you a spooky Christmas!