‘For no cause but for the healing and help of them’: medieval gynaecology as a female discipline

Guest post by Sarah Friedman, PhD candidate in English at the University of Wisconsin-Madison

Thanks to research grants from the Medieval Academy of America and the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Medieval Studies Program, I was able to travel to Cambridge University Library, Jesus College Library, and Trinity College’s Wren Library in the summer of 2022 to examine manuscripts that contain important representations of masculine vulnerability in late medieval literary and medical texts. A highlight of my experience was examining Cambridge, University Library, MS Ii.6.33, which is one of the manuscripts included in the University Library’s Wellcome-funded Curious Cures in Cambridge Libraries digitisation project.

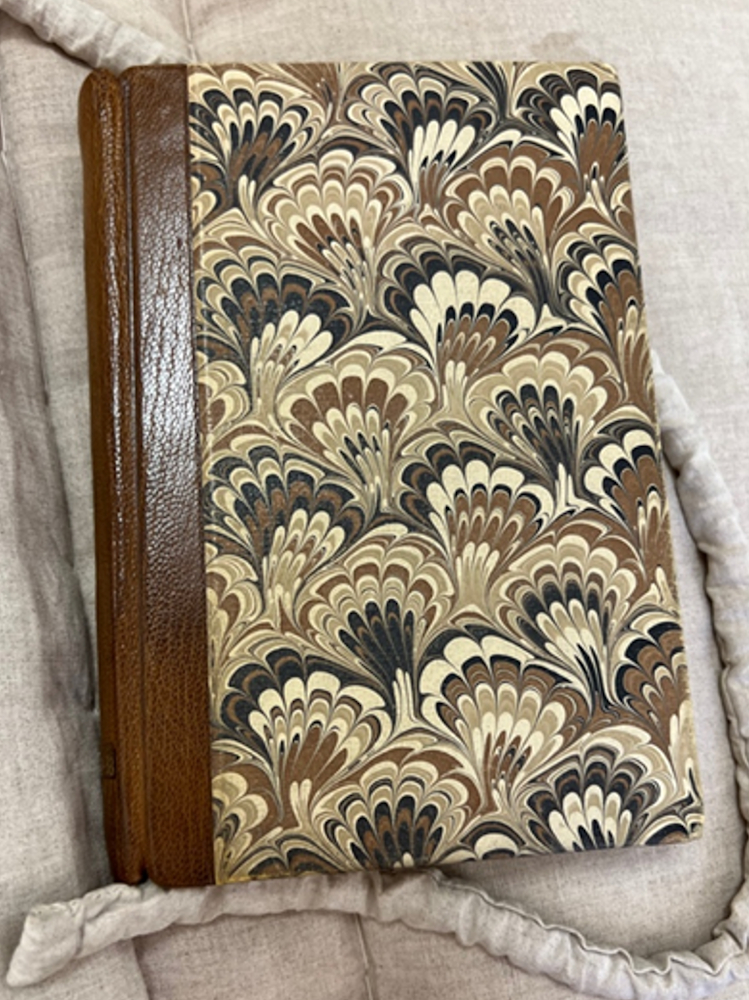

Cambridge, University Library, MS Ii.6.33 is a small composite manuscript, comprising two separately produced treatises on gynaecology: the branch of medicine focusing on women’s diseases, and especially relating to the reproductive system. Analysing these texts separately and in combination reveals an important theme in the manuscript: it presents gynaecology, above all, as a medical field developed and practised by women, and one that men may only engage with conditionally.

CUL MS Ii.6.33 contains a copy of a fifteenth-century Middle English prose gynaecological treatise that derives in part from an Old French translation of a twelfth-century Latin gynaecological text known as the Liber de sinthomatibus mulierum (‘The Book of the Conditions of Women’) (hereafter LSM). LSM circulated throughout Europe in the High and Late Middle Ages, both independently and as part of a group that included two other texts: De curis mulierum (‘On the Treatments of Women’) and De ornatu mulierum (‘On Women’s Cosmetics’) (hereafter, respectively, DCM and DOM). Each text in this group was written by a different author: while DCM was likely written by a woman named Trota of Salerno (fl. 12th century), LSM was probably written by a learned male physician. However, as Monica Green notes, when the textual group came into wider circulation throughout Europe from the thirteenth century onward, its contents – including LSM – were often entirely attributed to a female author named ‘Trotula’.

This translation of LSM is entitled ‘The Knowing of a Woman’s Kind in Childing’ in another copy of the work (London, British Library, Add MS 12195, f. 157r), but is presented without a title in CUL MS Ii.6.33 (it survives in three other manuscripts: London, British Library, Sloane MS 421A, ff. 2r-25v; Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 483, ff. 82r-103v; and Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Douce 37, ff. 1r-37r). The translation, which Green categorizes as ‘Eng1’ (previously ‘Trotula Translation A’), not only relies on the Old French version of the LSM but also draws from two other medical works: these are Non omnes quidem (the three opening words of that text), which itself draws on Muscio’s Gynaecia and other materials, and (pseudo-)Cleopatra’s Gynaecia.

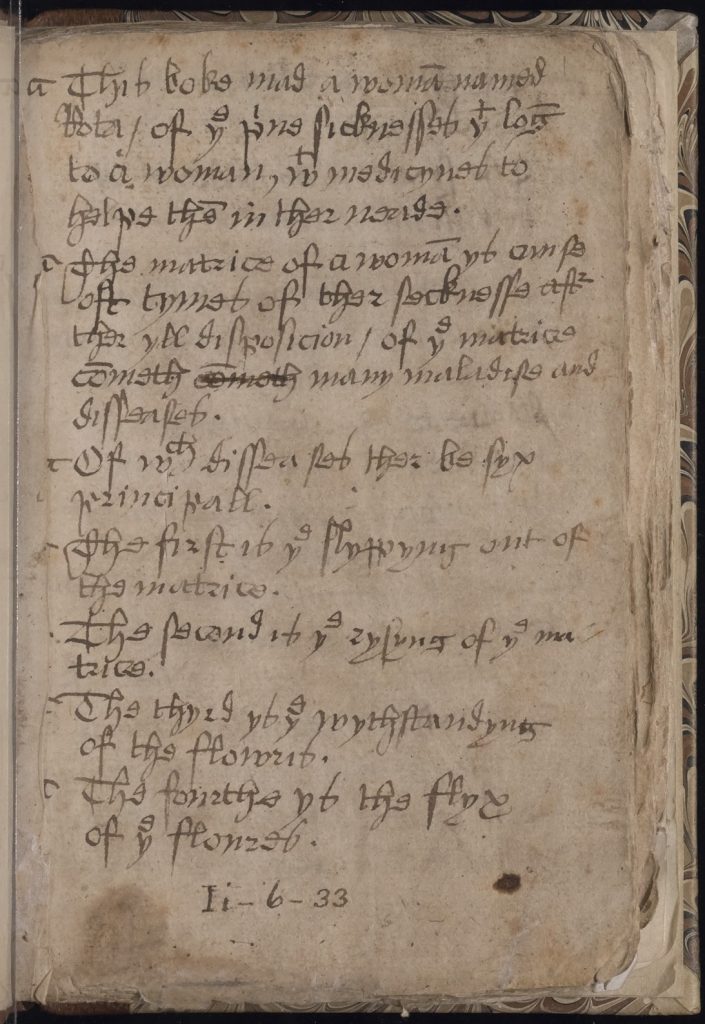

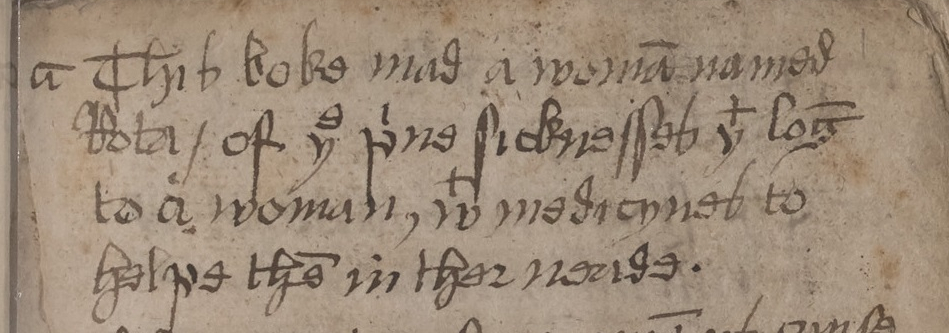

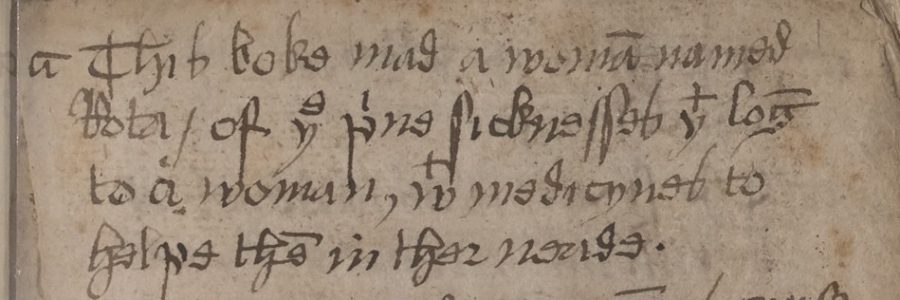

Unlike most other copies of the Knowing, which appear alongside various types of medical treatises in Latin and Middle English, that in MS Ii.6.33 is paired with only one other vernacular gynaecological text. Green classifies the latter as ‘Eng5’ (previously ‘Trotula Translation C’) and calls it The Boke Made by a Woman Named Rota (hereafter Rota), based on the attribution of the text to a certain ‘Rota’ that is written on the manuscript’s first leaf. Green and Alexandra Barratt, two experts on medieval gynaecology and codicology, both suggest that Rota was composed in the early sixteenth century and was shortly thereafter bound with the Knowing, which originally formed an independent book. Only one other copy of Rota has been identified – Glasgow, University Library, MS Hunter 403 (ff. 347-63) – which the physician and alchemist Sir Robert Greene of Welby (1467–1540) made for his own use in about 1544. However, this version is likely not a copy of CUL MS Ii.6.33 and does not contain the attribution to ‘Rota’. (Greene also copied and owned Cambridge, University Library, MS Ff.4.12, a compilation of alchemical texts).

The research that I completed using manuscripts such as MS Ii.6.33 will contribute to the first chapter of my dissertation. It will examine how gynaecological texts such as the Trotula and Rota would have emotionally affected male readers, and how the emotional imperatives that they prescribe could enable male readers to benefit from engaging in cross-gendered medical care. Green and Barratt have noted that, given the small size and focus of MS Ii.6.33, it was likely intended for practical use by a layperson and could have potentially circulated among midwives. However, later evidence of provenance indicates that, at least by the seventeenth century, this manuscript had passed through men’s hands. Moreover, there is strong evidence that the compiler of the Knowing, to some degree, wrote their work with a male audience in mind. I argue that MS Ii.6.33 both invited and discouraged cross-gendered acts of care from male readers.

In MS Ii.6.33, Rota opens with the statement that its subject is ‘the privy (private) sicknesses that belong to a woman, with medicines to help them in their need’. A male reader would have been immediately made aware that the following information was a product of female expertise. However, in indicating that Rota wrote this text for women in times of need, the author also reminds the reader of women’s physical vulnerability and the various bodily afflictions they suffered: slipping out of the uterus, rising of the uterus, ‘withstanding’ and ‘flux’ of the menstrual flow, delay in conceiving, and difficulty in delivering a child – the subjects of each chapter of the text. Women are presented as experts in their own supposed vulnerability – ‘in need’ but also knowing how to address this – which positions a male reader as an outsider stepping into a female medical territory.

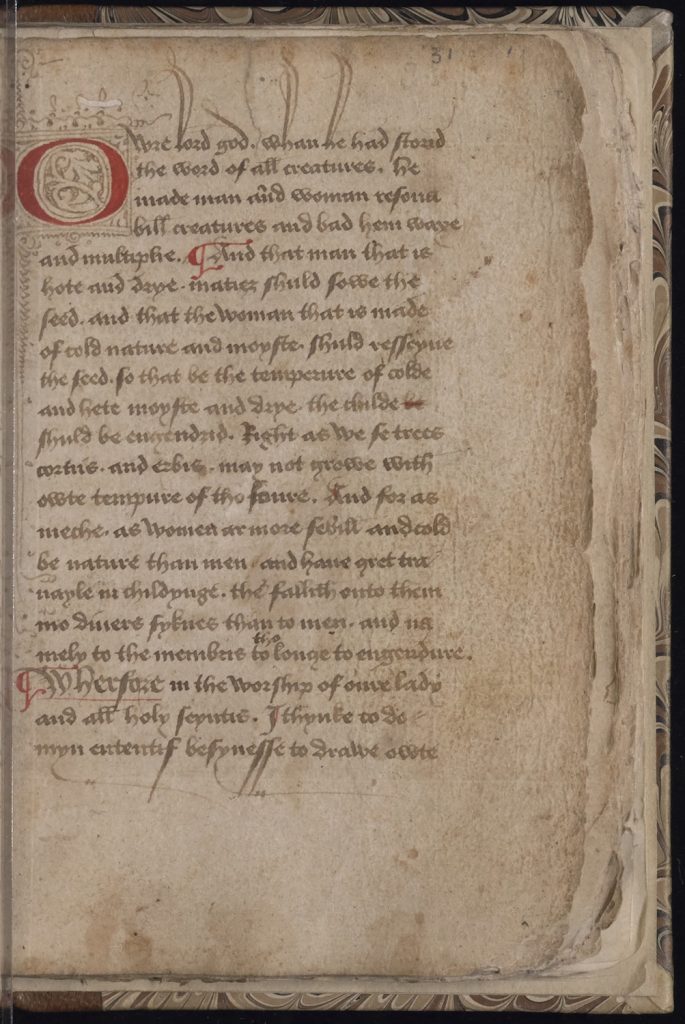

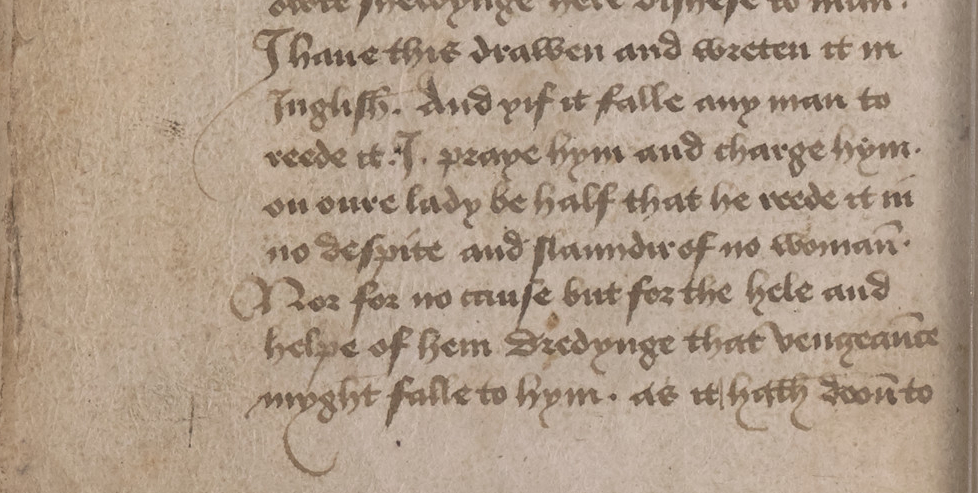

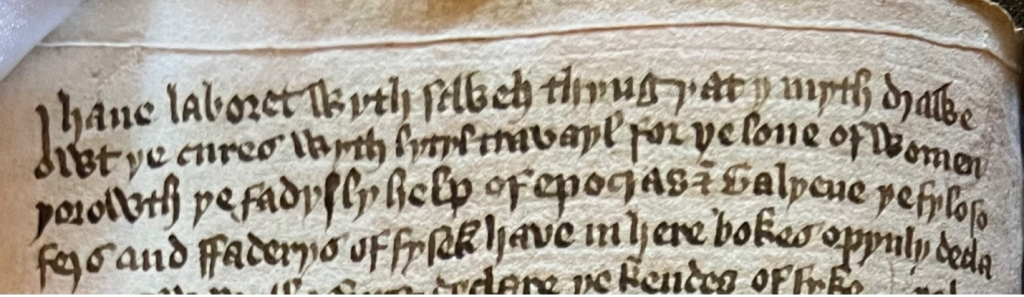

The Knowing‘s prologue, which begins on f. 2:1r, similarly warns male readers that they should only enter the realm of women’s medicine with specific intentions:

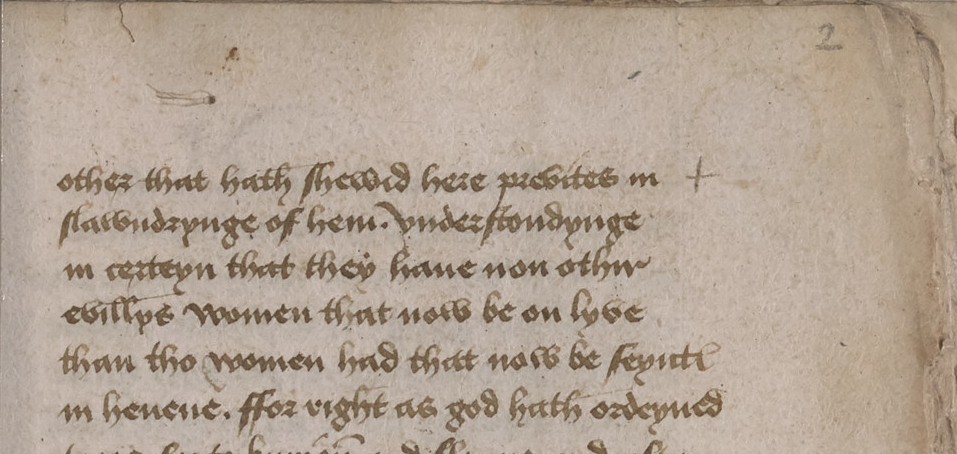

And if it happens that any man reads [this book], I ask and order him on our Lady’s behalf that he does read it without contempt or defamation of any woman and for no other reason than the healing and help of them, dreading that vengeance might fall on him as it has done to other [men] who have disclosed women’s secrets in slander of them, …understanding surely that women that are now alive have no more evils than women that are now saints in heaven.

Instructions to the male reader, The Knowing of a Woman’s Kind in Childing (MS Ii.6.33, ff. 2:1v-2r), modernised translation

The author is aware that reading this text might elicit negative feelings, even in well-intentioned male readers. They should approach it ‘for no other reason than the healing and help of [women]’ and must therefore read the text ‘without contempt’ (‘in no despite’, in the original Middle English). Furthermore, even if their intentions are good, they risk God’s punishment if they feel disdain for women’s ailments while they are reading.

Reproduced by kind permission of the Master and Fellows of Jesus College.

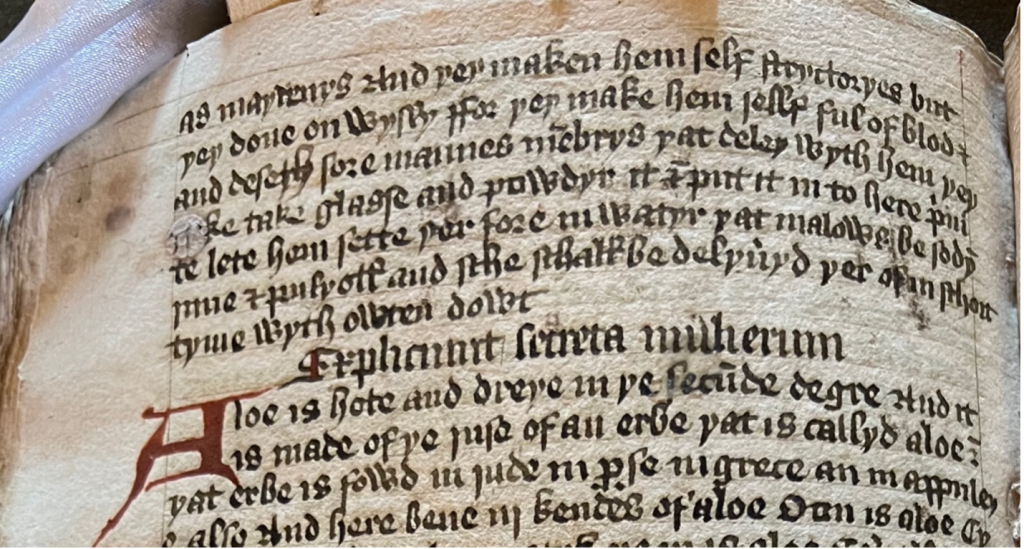

Comparison with a further version of the Trotula in Cambridge, Jesus College, MS 43 (ff. 70r-75v) highlights the significance of these texts’ emphasis on female expertise and appropriate reading by men (this text is also found in London, British Library, Sloane MS 121, ff. 100r-105r, and Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Lat. Misc. c. 66, ff. 83r-86v). This manuscript contains a condensed translation of chapters from the Latin Trotula group, which text is known as ‘Eng3’ (previously ‘Trotula Translation D’); the version found in this manuscript is ‘Eng3a’. It concludes with the rubric ‘Expliciunt secreta mulierum’ – ‘here conclude the secrets of women’ – emphasising the secrecy of the knowledge it contains. However, by acknowledging in the prologue the ‘help’ of Galen and Hippocrates as the ‘philosophers and fathers of physic’, the compiler situates this version of the Trotula within male-dominated medical practice.

Reproduced by kind permission of the Master and Fellows of Jesus College.

Such acknowledgements are also to be found in the prologues of the Latin LSM and the Old French translation used by the compiler of Knowing (which translation also acknowledges Cleopatra). However, the Knowing does not credit any specific physician, male or female, as the source of the knowledge it presents – and, in this manuscript, is bound with the Rota, a gynaecological text that is explicitly attributed to a female author. The Knowing‘s advice to male readers thereby gains further weight: it embeds gynaecology within a textual tradition of specifically female expertise – a tradition with which men may engage, but only with proper reverence towards women.

Sarah Friedman

Bibliography:

- Monica Green, Making Women’s Medicine Masculine: The Rise of Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynaecology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

- The Trotula: A Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine, ed. and trans. Monica Green (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001).

- Alexandra Barratt, The Knowing of a Woman’s Kind in Childing: A Middle English Version of Material Derived from the Trotula and Other Sources (Turnhout: Brepols, 2001).

- Monica Green, ‘A Handlist of Latin and Vernacular Manuscripts of the So-Called Trotula Texts, Part II: The Vernacular Translations of Latin Rewritings’, Revue Internationale Des Études Relatives Aux Manuscripts, 1 (1997), 80-104.

- Monica Green, ‘Obstetrical and Gynecological Texts in Middle English’, Studies in the Age of Chaucer, 14 (1992), 58-92.