Magnus Hirschfeld & sex reform

Post by Alina Wanitzek (Assistant Librarian, Department of Psychology)

In October 2022, San Francisco–based queer public historian and book dealer Gerard Koskovich came to Cambridge to share his work on Dr Magnus Hirschfeld (1868–1935), Founder in 1919 of the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (Institute of Sex Research) in Berlin, ahead of his publication on the subject. Hirschfeld is pictured above, seated between Bernard Schapiro on the left (Assistant Director of the Institut) and medical student Li Shiu Tong on the right. The talk was accompanied by a display of rare books at the University Library, featuring several early editions of Hirschfeld’s work, and it feels appropriate – as LGBT History Month draws to a close – to share these. This was an event hosted jointly by lgbtQ+@cam, an interdisciplinary research initiative in queer, trans and sexuality studies, and CamLibQ+, a network for queer library staff and allies in Cambridge. An internationally renowned German physician and sexologist, Magnus Hirschfeld was not only a pioneering advocate for homosexual and transgender emancipation, but also a pioneer in the use of reproduced images to advance the work of sex reform. In his illustrated talk, Koskovich analysed the visual strategies in Dr Hirschfeld’s publications from the 1890s to the 1930s. His presentation traced the innovative, complex, contradictory and problematic ways Hirschfeld used images to advance his arguments for medical, legal, political and social respect for homosexual and transgender people.

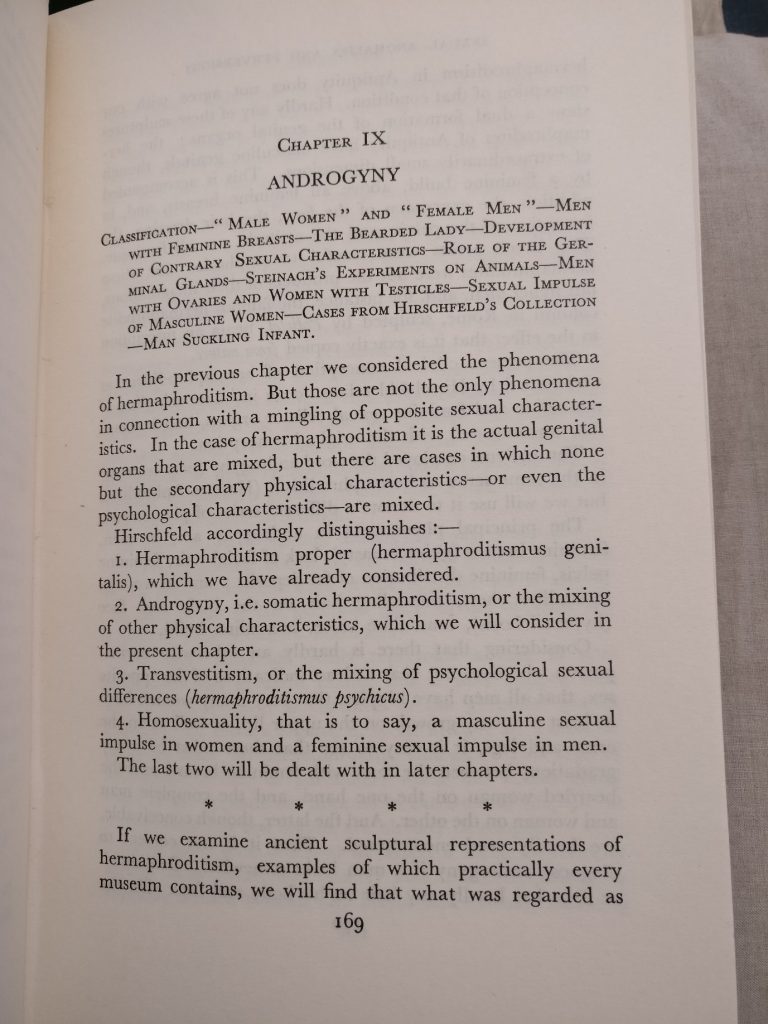

Our display was an opportunity for attendees to view some of the titles mentioned in the talk in physical form. The publications, ranging from 1900 to 1937, also give a sense of how Magnus Hirschfeld’s own ideas developed over time: while early works seem to conflate homosexuality and gender non-conforming habits such as cross-dressing, a posthumously published chapter on ‘androgyny’ distinguishes physical sex characteristics from gender identity and sexual attraction. Many of the books are part of the Library’s ‘Arc’ collection, formed in the early twentieth century for books of an erotic or sexual nature.

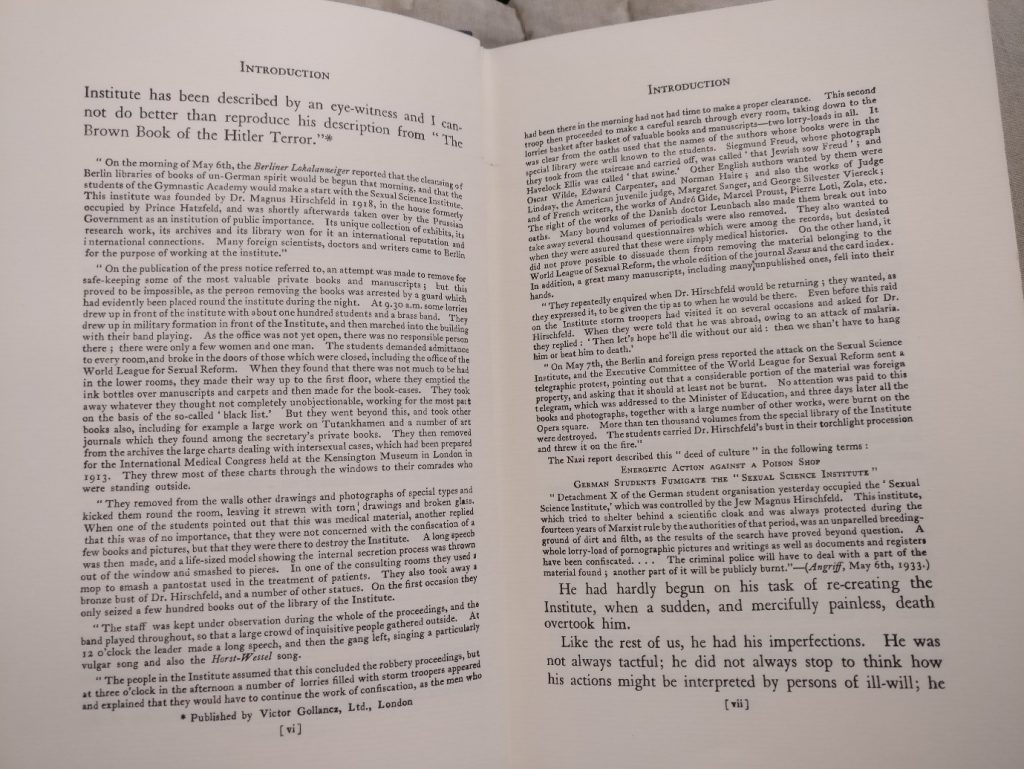

It’s striking how the case studies included in these books make the people portrayed come alive and feel close to us even now. These were regular people with their own lives and opinions, and they didn’t always agree with Hirschfeld’s medical conclusions about themselves. We also have a real treasure trove in the fourth volume of Hirschfeld’s magnum opus Geschlechtskunde, the Bilderteil: over a thousand images of all conceivable kinds of variations of gender and sexuality, from ancient Greek statues to people hanging out at a lesbian bar in Weimar-era Berlin.

Magnus Hirschfeld spent the last years of his life in exile following persecution by the Nazis, who proceeded to burn his research institute’s remarkable library of books related to studies in sexuality and gender. We are lucky that he was such a prolific author, so that copies of his work have survived here at Cambridge and in other places around the world. The images which follow give an introduction to some of the books displayed.

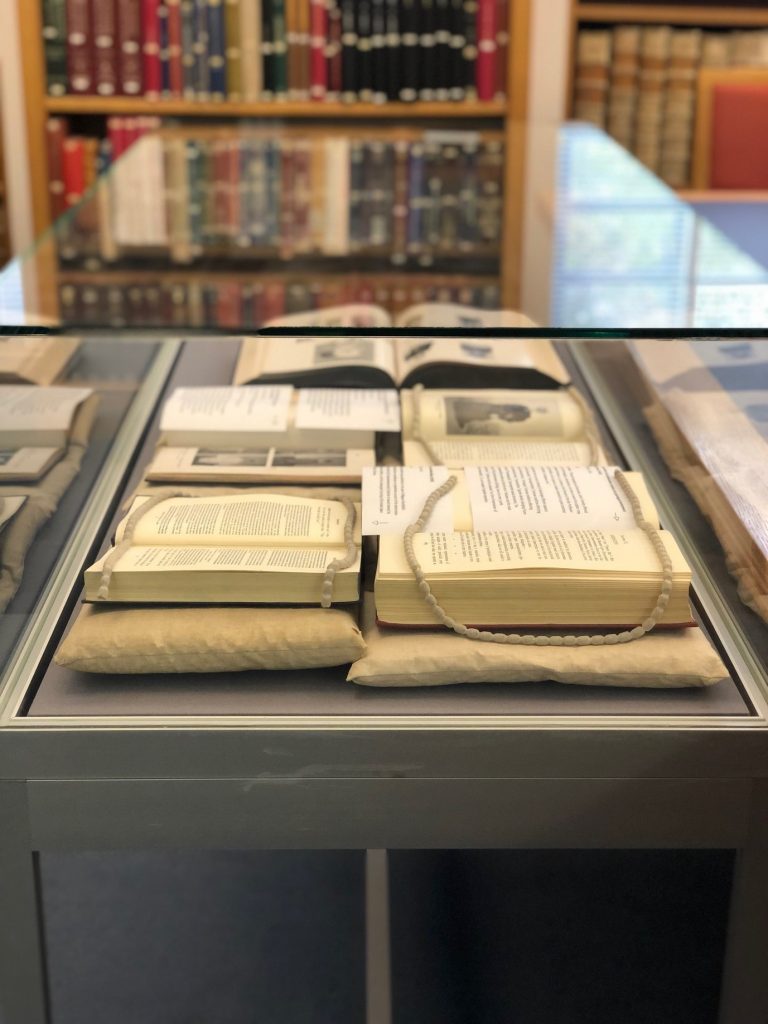

The Jahrbuch (image 1) was a yearly publication launched to encourage and disseminate research on homosexuality and nonnormative gender. This photograph shows a 41-year-old “man” who is described as “markedly effeminate”. In their own words the subject wishes that their being assigned male turn out to be an error and that they be declared female instead. They describe a “blissful, heavenly feeling” when dressing in female attire. The chapter makes a point of mentioning that they are mentally and physically strong – there’s nothing wrong with them, their behaviour isn’t a sign of illness.

Content note: suicide. This chapter (image 2) lists four cases of suicide: ‘4 Fälle von Selbstmordversuch resp. Selbstmord von Scheinzwittern’ (i.e. 4 cases of suicide attempts or suicides of pseudohermaphrodites) of individuals whose assigned gender didn’t match their identity and who were also intersex. One person, assigned female at birth and raised as a girl, had requested to be formally recognised as a man with no success, five years before eventually taking their own life. The chapter notes that the suicide could likely have been avoided if their request had been accommodated.

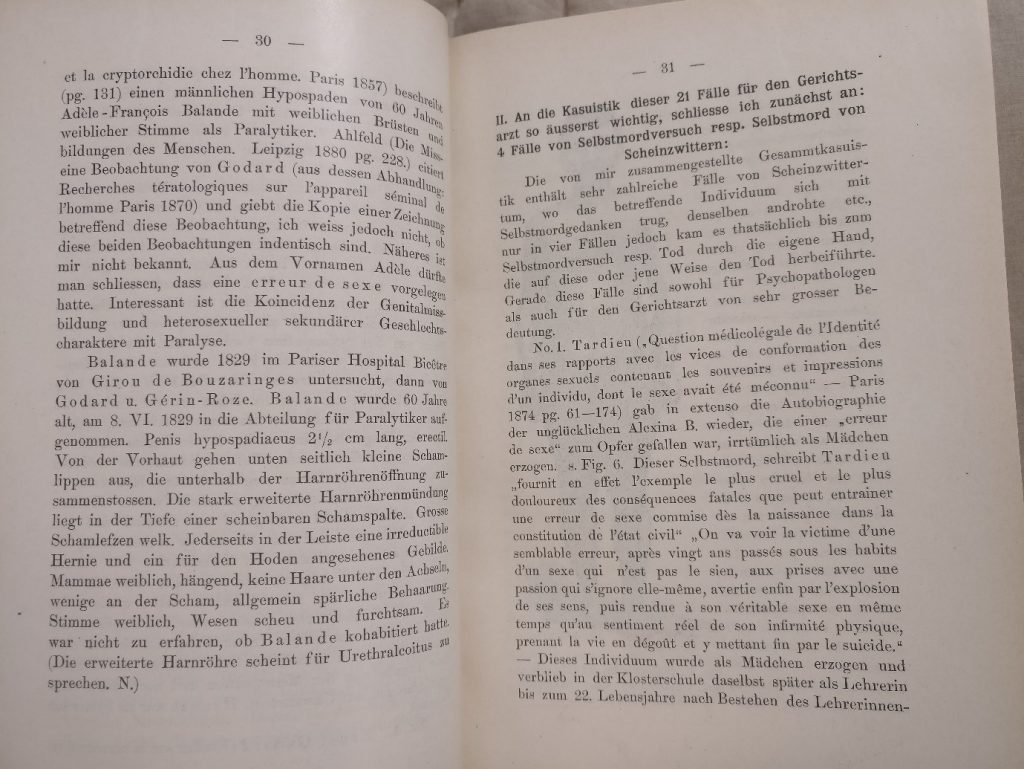

The photographs in the Geschlechtsübergänge (image 3) depict Friederike S., an intersex person who was assigned female at birth but developed more typically male characteristics during puberty. The description, ‘Pseudohermaphroditismus masculinus bei überwiegend männlichem Habitus (Error in sexu)’ translates as ‘Pseudohermaphroditismus masculinus with predominantly masculine presentation’. They are solely attracted to women. The accompanying report is very medicalised and concludes based on their biology and sexuality that they are “really” a man and were assigned female in error. Friederike says that they would rather have been “born a man”, but have always considered it futile to “fight their nature” – they decline Hirschfeld’s suggestion (based on his medical assessment) to live as a man going forward, as they worry it would cause a stir and jeopardise their social standing.

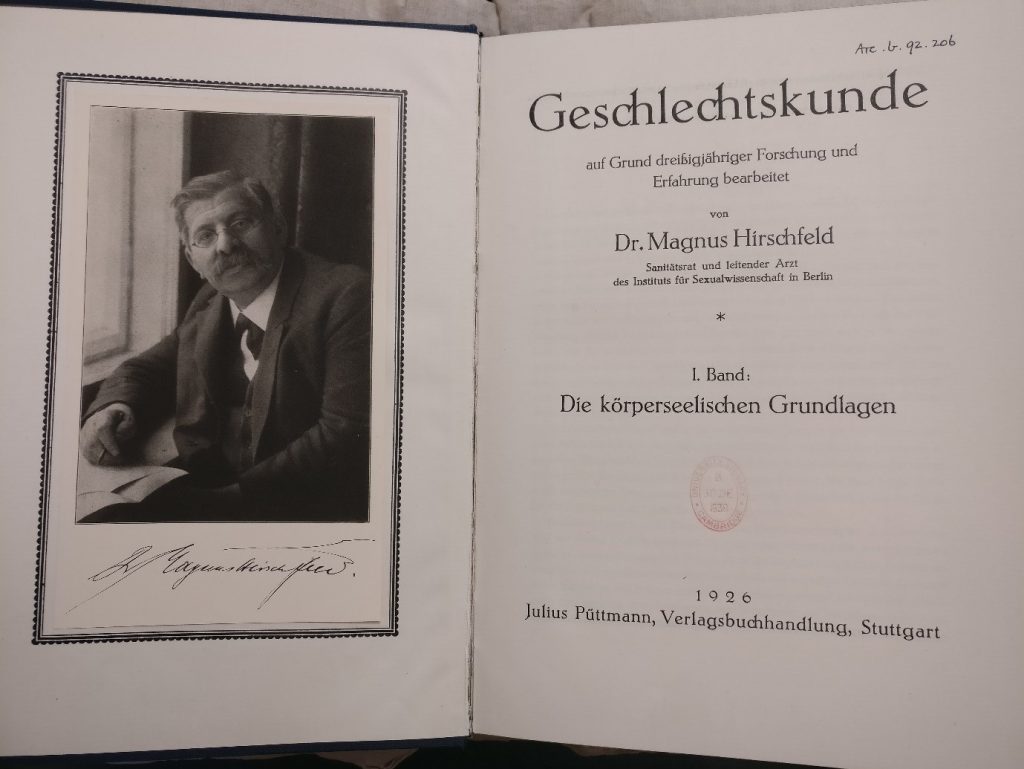

This section (image 4) quotes sources on the idea that homosexual individuals can be valued and useful members of society. Unfortunately this is framed as “making up for their physical failings” (their sexuality and the resulting lack of biological children) with intellectual or cultural achievements.

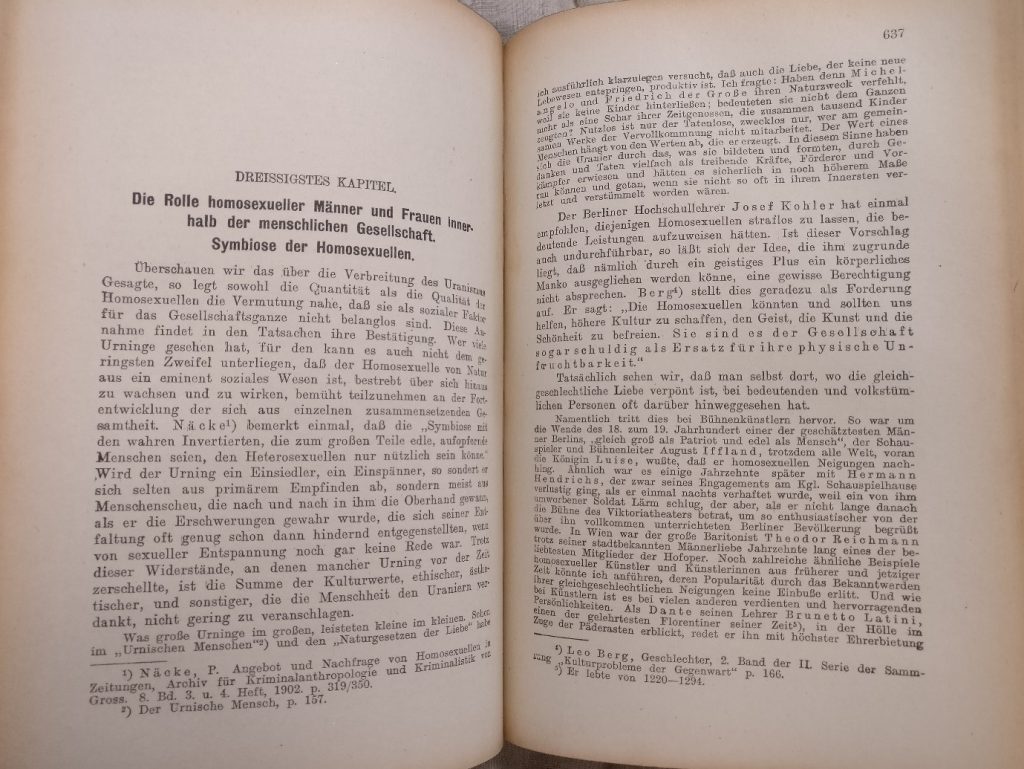

Geschlechtskunde (image 5) is a five-volume work that Hirschfeld compiled after decades of research and professional practice as a doctor. The foreword stresses that it’s the result of an entire working life in the field of sex and gender, written “aus der Praxis für die Praxis, aus dem Leben für das Leben” – “from practice for practice, from life for life” – unlike other existing works on the topics that are not based on experience or are compiled without a cohesive framework.

This volume (image 6) is entirely pictures; here we see ‘Virile Frauenköpfe’, i.e. virile women’s heads. These portraits of women with masculine features include Radclyffe Hall, author of the lesbian novel The Well of Loneliness (1928), which became the subject of moralistic legal battles after publication.

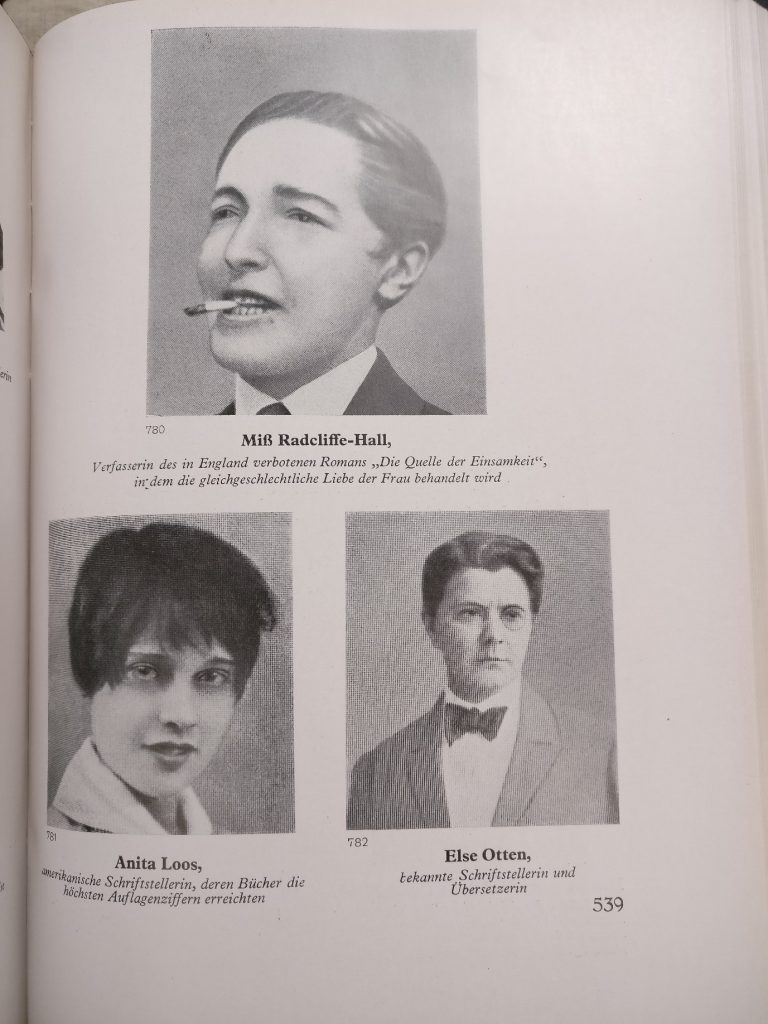

This English translation (image 7) was published in the year of Magnus Hirschfeld’s death. The introduction reproduces an eyewitness account of the destruction of Hirschfeld’s Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (institute of sexual science) by Nazi students and soldiers, and the subsequent burning of the books taken from the institute’s library.

From the preface: “Sexual Anomalies and Perversions (image 8), which is hereby offered to students, criminologists, educationists, and others to whom the subject may be of professional interest, is a summary of the life-work of the late Professor Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld, and is issued as a modest memorial to a great scientist and a warm-hearted, courageous man.” In the chapter shown we can see an attempt to disentangle different aspects of sex, gender and sexuality: “hermaphroditism” (intersex conditions affecting the primary sex characteristics), “androgyny” (intersex conditions affecting secondary sex characteristics), “transvestitism” (gender identity diverging from assigned sex) and “homosexuality” (same-gender sexual attraction). The chapter on transvestitism points out that the term “indicates only the most obvious aspect of this phenomenon [clothing], less so its inner, purely psychological kernel”. Clothes must be conceived “as a form of expression of our innermost personality”, i.e. as an aspect of gender expression.