A newly-discovered Malay manuscript in Erpenius’ library: An old booklet of supplication

While reconstructing the personal library of Thomas Erpenius (d. 1624) kept at Cambridge University Library (CUL) as part of my Munby fellowship, I have been able to find some lost manuscripts or identify some new works whose background and language were not specified nor explained in former studies. One of those manuscripts is CUL MS Dd.3.82, a small booklet of supplications and Qur’anic verses (e.g., Q21:89).

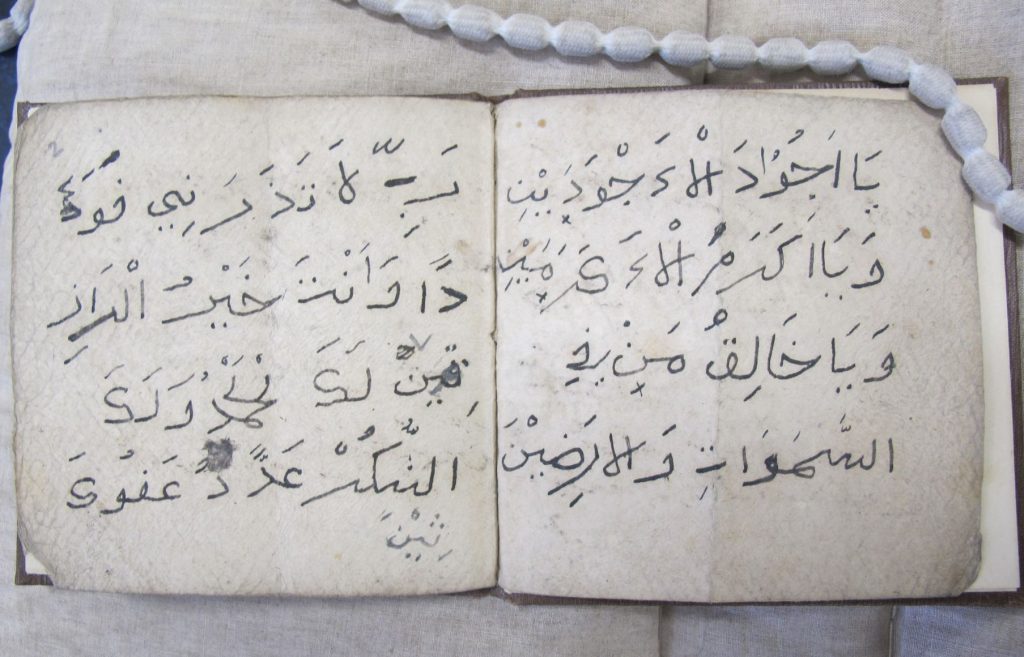

It consists of thirteen folios, measuring 10.3 x 10 cm. The initial Latin title given to the manuscript at CUL in the 17th century is Preces Arabicæ Mahumetanicæ (Muhammadan/Muslim Arabic Prayers). Edward G. Browne (d. 1926), the main cataloguer of the CUL’s oriental collections, listed this manuscript as an Arabic source and limited his description just to a few lines about its theme and size.[1] But a closer look at Dd.3.82 reveals that it was written by a local scholar from Indonesia. Philippus Samuel van Ronkel (d. 1954) and other experts of Malay-Indonesian manuscripts and literature who have examined the CUL collections remained silent about the origin and content of this manuscript.[2]

MS Dd.3.82 is partially copied on dluwang/daluang, a local Javanese paper (ff. 1–3r, 11v–13r) which is “hand-made from the beaten bark of the paper mulberry tree, Broussonetia papyrifera, called pohon saeh in Indonesia”.[3] Other parts are copied on European paper, also featuring traces of a watermark (ff. 3r–11r). Both pen and orthography of the manuscript demonstrate the Indonesian background of the manuscript.

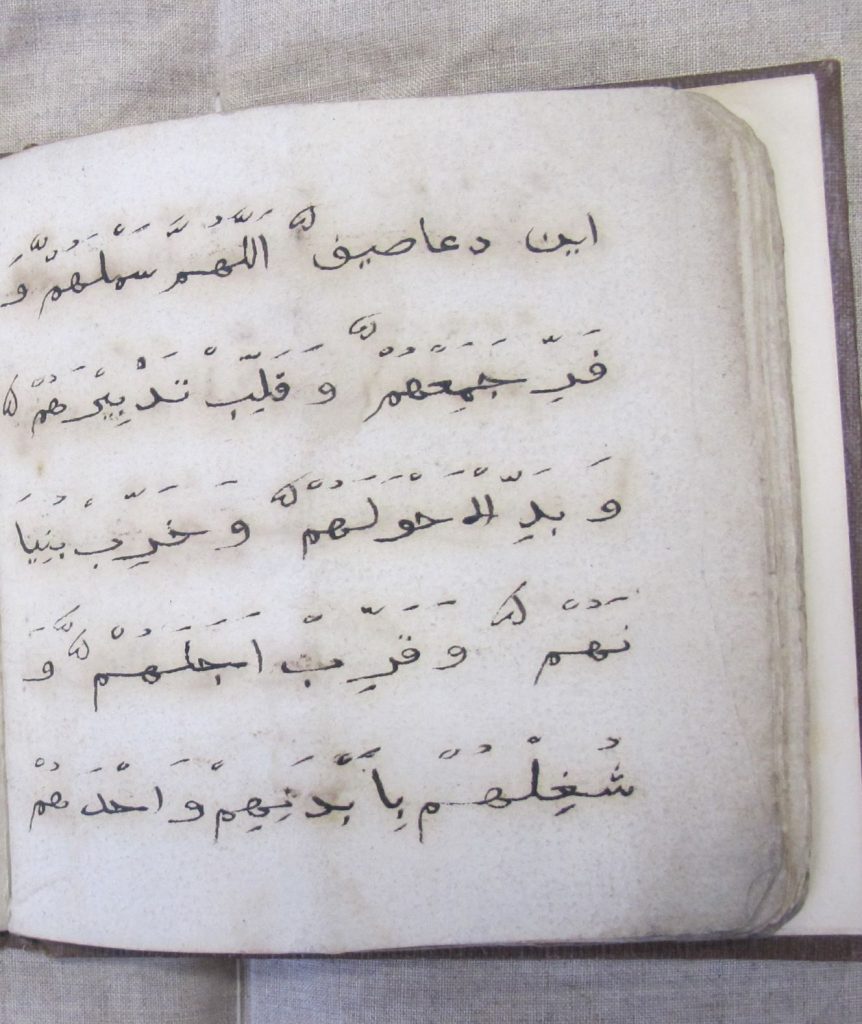

There is a supplication entitled«این دعا صیف» (ini doa Sayfi) from ff. 11r–13r, which is a corrupted form of «دعا سیفی» (Du‘ā-yi Sayfī).[4] This supplication used to be recited for protection from enemies and infidels for which it was also called the “Victory Supplication”.

Parts of this supplication are ascribed to the classical thinker, Shaykh ‘Abd al-Qadir al-Gilani (d. c. 1166 AD).[5] It is said that Muslims may eradicate darkness, injustice, and infidelity and protect themselves from natural disasters like earthquakes and thunder by reciting this supplication. It is known that Shi‘i communities paid a particular attention to this supplication and applied it in their literature and customs.[6] Following the Shi‘i [and Sufi] traditional sources, Dd.3.28 provides readers with a recitation formula regarding the frequency of its repetition. The numbers used for repetition of supplicatory phrases are written in Jawi (Malay).

To clarify my point, the Malay title of ini doa Sayfi (this is the Supplication of Sayfī), and the repetition formula of empat/ampat pulu kali (viz., to be recited for forty times) are shown in bold:

این دعا صیف. اللّهُمَّ سَملَهُمّ وَفَرِّ جَمِعهُم وَقَلِّب تَدبيرَهُم وَبَدِّالاَحوَلَهُم. وَخَرِّب بُنِيَانَهُم. وَقَرِّب اَجَلَهُم. وَشغِلهُم بِاَبدَنِهِم وَاحدَهُم اَحدَّ عرامـڤـت ڤـوله کال مُقتَدِیرِ. امـڤـت ڤـوله کال يَا قَهَّارُ. امـڤـت ڤـوله کال يَا جَبَّارِ. امـڤـت ڤـوله کال اللّهُمَّ قُّرُهُم بِقَهَارِ يكَ وَجَبَرَهُم بِجَبَرِيكَ وَ سَبَّهُ زُّمُل جَمِیع وَیُودُ نّدَ بور. بَلِسَعتِ مَوّعِدُهُم وَسّاعَت اَدهَ وَّاَمرَ رَبَّنَا تَقَبَّل مِنَّا اِنَّكَ أنتَ سمِيعَ العليم. امـڤـت له كل اِلهی قتلَت وهلَكهُم تهلِلَ وَدَمرَهُم تَدمِيرَ. اِلَهِي لعَالِمين ياخير لَناسِيرين. لا اله الله محمد رسل الله. اِلَهي برکة القرآن … ڤـولا جوز.

Traces of local pronunciations like Syukur instead of Shukr (Praise of God) and Abu Bakar instead of Abu Bakr and uncommon recitation modes are detected, which open more windows and doors for scholars regarding the early reading of Islamic materials in pre-17th century Indonesia. In addition, the existence of a large number of grammatical and diacritical errors suggests that the manuscript was produced when Islam in Java was still in its infancy…when the concepts of “we” (Muslims) versus “them” (infidels) were still common.

A textual edition and translation of the manuscript is forthcoming.

[1] Edward G. Browne, A Hand-List of the Muhammadan Manuscripts, including All those Written in the Arabic Character, preserved in the Library of the University of Cambridge (Cambridge: at the University Press, 1900), p. 285.

[2] E.g., Ph S. Van Ronkel, “Account of six Malay manuscripts of the Cambridge University Library,” Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land-en Volkenkunde van Nederlandsch-Indië, 1ste Afl (1896), pp. 1-53. Merle Calvin Ricklefs, Petrus Voorhoeve, and Annabel Teh Gallop. Indonesian Manuscripts in Great Britain: A Catalogue of Manuscripts in Indonesian Languages in British Public Collections. New Edition with Addenda et Corrigenda (Jakarta: École française d’Extrême-Orient. Perpustakaan National Republik Indonesia. Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia, 2014).

[3] Annabel T. Gallop, “Malay Manuscripts on Javanese Paper”. BL Asian and African studies blog (2014) <https://blogs.bl.uk/asian-and-african/2014/07/malay-manuscripts-on-javanese-paper.html> Access date: 28.03.2023

[4] Although the content is different from the popular Du‘ā-yi Sayfī, widely known as Hirz al-Yamani in South Asian and Middle Eastern contexts. See: Majid Daneshgar, “A Sword that Becomes a Word: Supplication to ʿAlī b. Abī Tālib and Dhū’l-Faqār”, Mizan (2017) <https://mizanproject.org/a-sword-that-becomes-a-word-part-1/> Access date: 28.03.2023. And Majid Daneshgar, “A Sword that Becomes a Word: The Supplication to ʿAlī in a Malay Manuscript”, Mizan (2017) <https://mizanproject.org/a-sword-that-becomes-a-word-part-2/> Access date: 28.03.2023.

[5] Muhammad Baha’ al-Din, Majmu‘a Awrad wa-Ahzab al-Tariqa al-Naqshbandiyya, ed. Ahmad Ziya’ al-Din Afandi. With Asim Ibrahim al-Kayyali (Beirut: Dar al-Kutub al-‘Ilmiyyah, 2013), p. 276.

[6] Muhammad Baqir al-Majlisi, Miftah al-Jinan, ed. ‘Ala’ al-Din A‘lami (Beirut: Mu’assasa al-A‘lami li l-Matbu‘at, 1423), vol. I, p. 528.