The Oldest Javanese Islamic Text at Cambridge University Library

This post is co-written by Dr Majid Daneshgar (Munby Fellow, CUL) & Prof. Edwin Wieringa (Professor of Indonesian Philology and Islamic Studies, University of Cologne, Germany).

The subject of this post, CUL MS Gg.5.22, a manuscript from the collection of Thomas Erpenius, is a Javanese text containing three parts, (1) mainly dealing with Muslim law (fiqh) discussing the principal religious duties, followed by short sections on (2) divination, and (3) the principles of faith in the form of a catechism. Soon after the death of Erpenius, a handlist of his personal library was published, but the compilers had to limit themselves to a most tentative description of this volume:

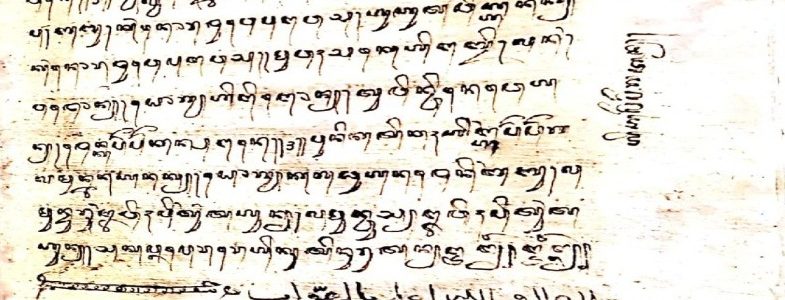

Liber Indicus alijs characteribus ignotis, & magnam partem aliquo modo referentibus omega Graecorum, cum longis caudis, rectā deorsum tendentibus, in Fol.[1]

A book of Indian background with unknown characters, and a large portion of it somehow reminds us of the letter omega (Ωω) in the Greek language, with long tails, extending straight down on the right. In folio (large) size.[2]

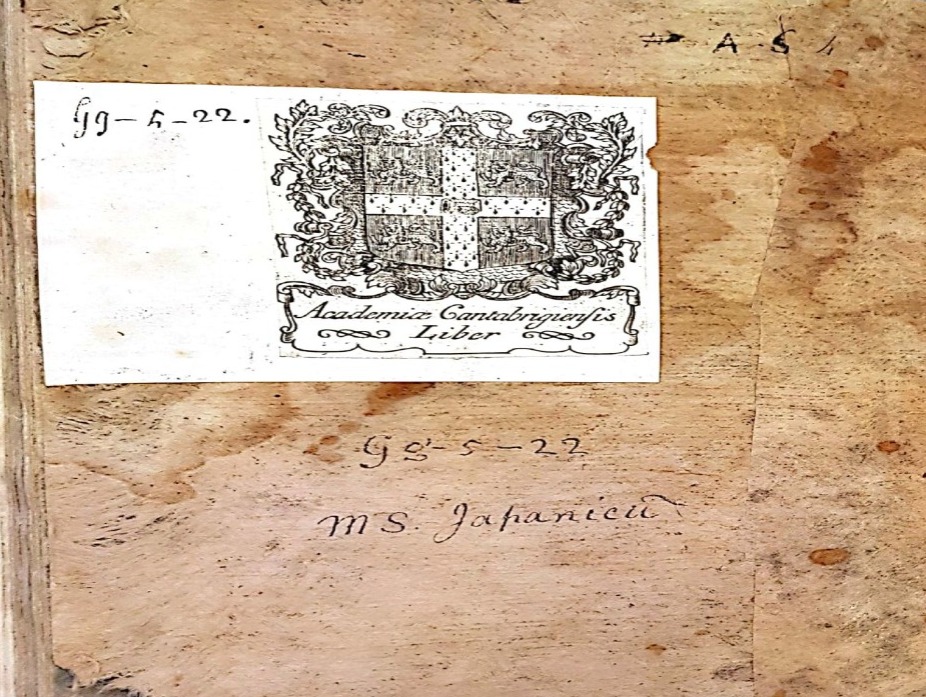

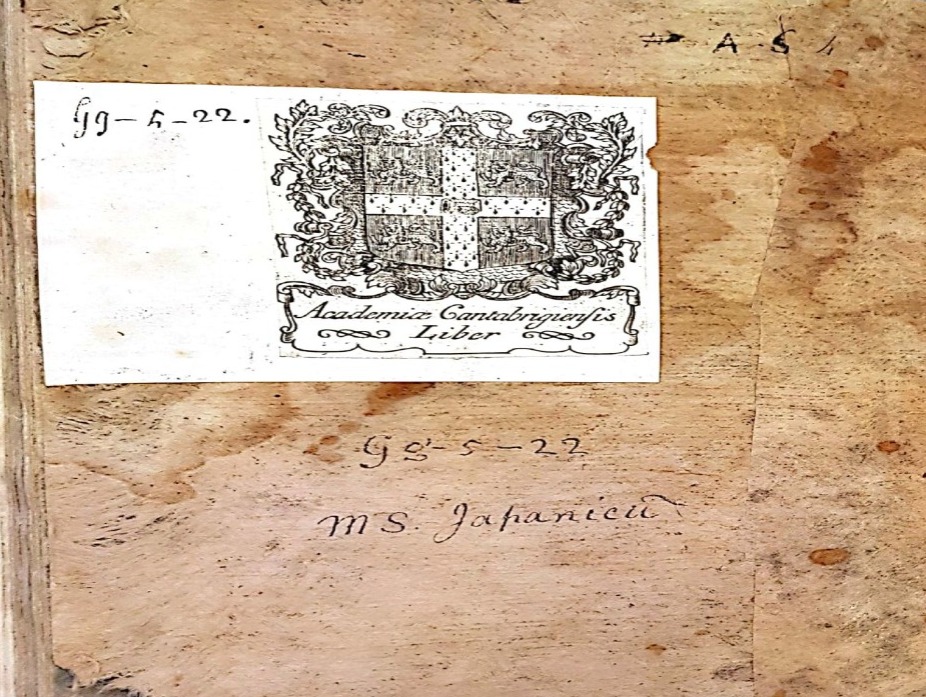

For a very long time, the language and contents of this book would remain a mystery to Europeans. Since Gg.5.22 was part of Erpenius’ Indian and East Asian items, including an incomplete Chinese book of medicine (Sel.3.273),[3] Jonathan Pinder, the first cataloguer of Erpenius’ collection at Cambridge University Library, in consultation with Abraham Wheelock (d. 1653) and possibly other English royal servants, described the manuscript as a “Japanese Book” (‘Liber Japonica’) with the classmark of A.β.4. As is clear from two Latin titles added to the manuscript after its arrival in England, knowledge of Asian languages was still quite poor in 17th– and early 18th-century Europe:

Front Matter: Liber Japonicus Charactin Japonica (‘A Japanese book with Japanese characters’) [added in England after 1625 when the collection was bought by George Villiers].

Back Matter: gg–5–22 ms. Japanicũ (‘Gg.5.22 Japanese manuscript’) [added after 1715, when the two-letter classmarks (like Gg.) were created] (Fig 1)

Physical Features and Provenance

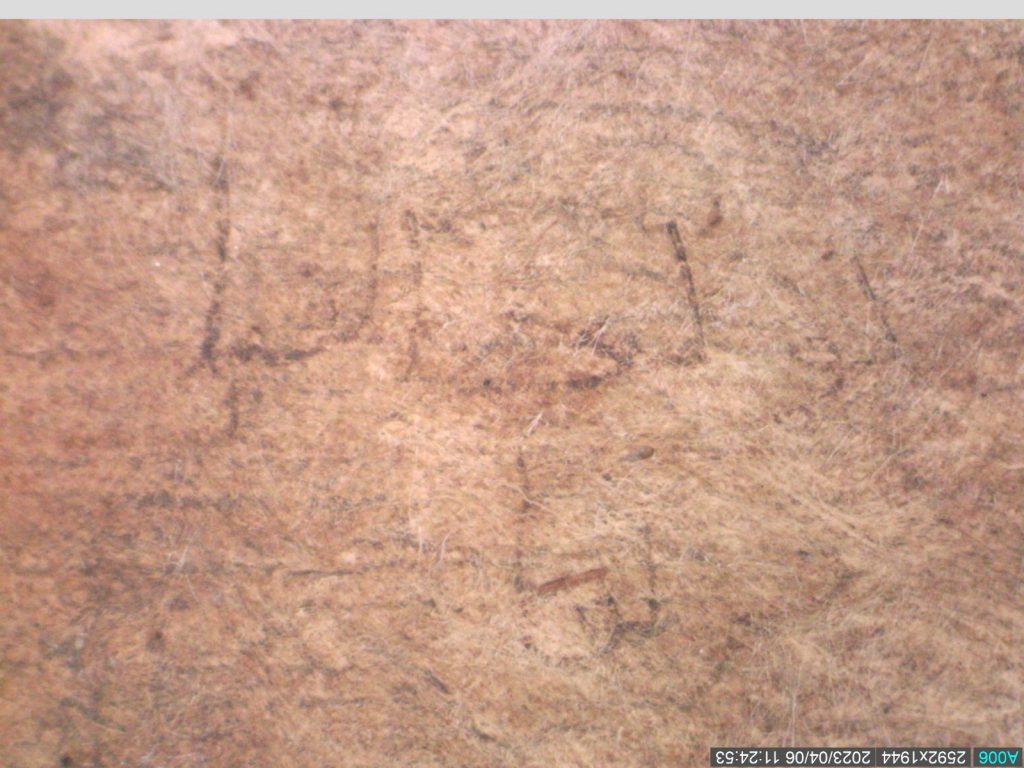

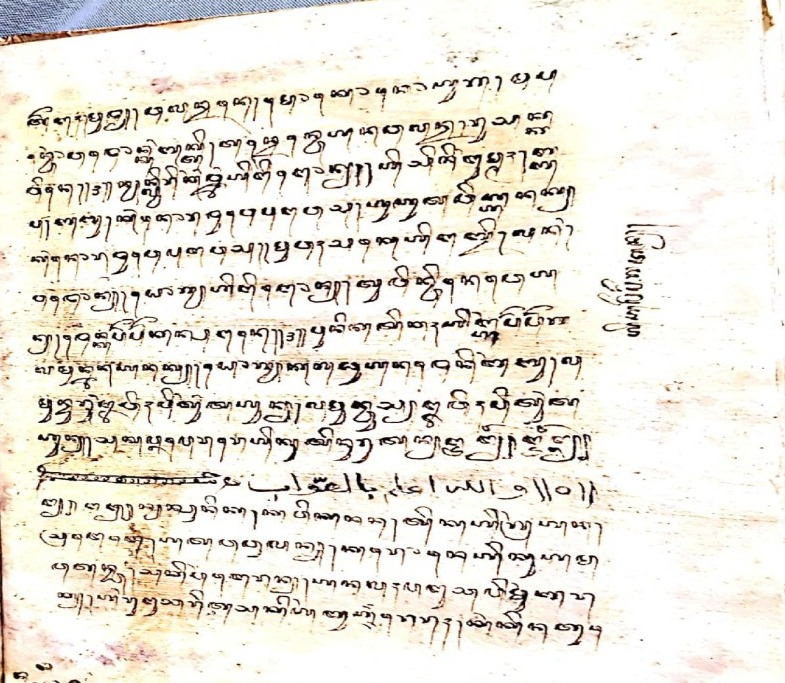

Gg.5.22 has been copied on Javanese paper called dluwang (or daluang), which is “hand-made from the beaten bark of the paper mulberry tree, Broussonetia papyrifera, called pohon saeh in Indonesia.”[4] The manuscript is loose and fragile. It has been divided into four parts by a European using Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3, 4), which can also be seen in other manuscripts of Erpenius. The first folio of the manuscript Gg.5.22 provides some valuable information: (a) traces of names and titles in Arabic scripts, but only legible under a microscope (Fig 2);[5] (b) traces of an illuminated frame; and (c) the capital letter “S” on top of a floral painting. The letter “S” may refer to the way “Erpenius consistently added ‘S’ to indicate Scaliger’s work [Kitab al-amthal].”[6] Assuming that the manuscript once previously belonged to Scaliger, the terminus ante quem could be established at 1609, the year of Scaliger’s death.

Content

Gg.5.22 is one of the oldest extant Javanese Islamic manuscripts, originating from the period of transition from Hindu-Buddhism to Islam. Although its provenance is unknown, it is most likely from Java’s north coast (pasisir) where it must have come into the hands of a European and it was subsequently brought to Europe. As is common for Islamic texts, the opening page of the first part (f. 2r) starts with the basmala which is rendered into Javanese as sakehing puji ing Allāh, Pangeraning alam kabeh… (All praise is due to Allah, the Lord of all worlds). The term used for God is the Javanese word Pangeran (Lord), which in Modern Javanese became a standard term for a prince but here still has its pre-Islamic Old Javanese meaning, i.e. “the person one waits upon, the lord or master.”[7] Basic rituals and legal instructions of the relatively new faith are discussed in the first text (ff. 2-36), mentioning three Arabic books (kitab) as sources (f. 2r), namely (1) kitab Muharar (known in Arabic as al-Muḥarrar or “The Carefully Edited Book”), (2) kitab Ilah (that is, Iḍāḥ fī l-Fiqh or “Elucidation of the Fiqh”), and kitab Sujjai, probably the compendium of Shāfiʻi fiqh which was named after its author (Abū) Shujā‘ (d. after 1196 CE), whose legal treatises were also copied and translated into Malay, and on dluwang paper.[8] Intriguingly, these three well-known works are mentioned in the major Cĕnthini as the most authoritative textbooks of Islamic law.[9] The latter work was compiled in the early 19th century although partly from much older materials.

The first part of Gg.5.22 contains several corrections and marginal notes, ending with the Arabic phrase ولله اعلم بالصّواب between Javanese punctuation marks (Fig 3).

Like the Malay manuscript Dd.5.37 in Erpenius’ library, the next part includes a short divinatory text. It is about solar and lunar eclipses (ff. 36-37), followed by short fragments of a catechism (ff. 37-41). The signs of the heaven concerning the sun and moon are interpreted as “signs of the Lord” (tandha saking Pangeran). Compared to the episode on the same subject in the major Cĕnthini, the information is rather succinct. For example, a lunar eclipse in the third month of the Islamic calendar (Rabingulawal or Rabīʻ al-awwal) portends that many people will experience starvation, while the major Cĕnthini predicts many deaths but also many rains and storms. Interest in the occult sciences is testified in many Javanese manuscripts, being part and parcel of Javanese primbon (handbooks or notebooks). For example, a 16th-century primbon edited by Drewes contains a short divinatory text on involuntary muscular twitches.[10] The final text in Gg.5.22 is called kitab usul agama, that is the book on uṣūl al-ḍīn, dealing with the essential beliefs in Islam that every Muslim needs to know. This primer is in a “question and answer” (soal kalawan jawab) format, which is a catechism in the form of “if you are asked…” (lamun sira tinakonan…), “your answer [is]…” (sauranira…).

[1] See, Gerardus Joannes Vossius, Oratio in orbitum Thom. Erpenii, oriental. linguarum in Acad. Leidensi professoris accedit funebria carmina: item catalogus librorum orient. in bibliotheca Erpeniana (Lagduni Batavorum: ex Officina Erpeniana, 1625).

[2] For further information about this description and the history of other manuscripts at Cambridge University Library, see John C. T. Oates, Cambridge University Library: A History: From the Beginnings to the Copyright Act of Queen Anne (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), I: 223. As far as we know, the first description of the manuscript as a Javanese text was made by Ricklefs and Voorhoeve in 1977; see M. Ricklefs, P. Voorhoeve and A. T. Gallop, Indonesian Manuscripts in Great Britain: A Catalogue of Manuscripts in Indonesian Languages in British Public Collections (Jakarta: Ecole française d’Extrême Orient, Perpustakaan Nasional Republik Indonesia [and] Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia, 2014), 55.

[3] Our thanks go to Yan He, Head of the Chinese Section at CUL, for her helpful advice.

[4] Annabel T. Gallop, “Malay Manuscripts on Javanese Paper”. BL Asian and African studies blog (2014) <https://blogs.bl.uk/asian-and-african/2014/07/malay-manuscripts-on-javanese-paper.html> Access date: 20.05.2023

[5] Our thanks to Shaun Thompson of CUL’s Conservation and Collection Care department for providing us with these photographs.

[6] Kasper van Ommen, “Josephus Justus Scaliger”, in Christian-Muslim Relations: A Bibliographical History, edited by David Thomas and John Chesworth, et al. (Leiden: Brill, 2016), viii:553-560.

[7] M.C. Ricklefs, Mystic synthesis in Java. A history of Islamization from the fourteenth to the early nineteenth centuries (Norwalk: EastBridge, 2006), 22.

[8] See Ms Or_15 at Marburg University Library, Germany.

[9] For an identification of these works and further bibliographical details, see Soebardi, “Santri-religious Elements as Reflected in the Book of Tjĕnṭini,” Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 127 (1971), 335-336.

[10] G.W.J. Drewes, Een Javaanse primbon uit de zestiende eeuw (Leiden: Brill, 1954), 94-95.

This is an important discovery. Are there plans for a Romanised edition or an Indonesian and/or English translation? These would be invaluable resources for scholars concerned with the early history of Islam in Southeast Asia.

Dear Mark,

From the authors of the blogpost:

“Thank you very much. A very worthwhile suggestion.”

Very interesting.

I was unaware that the UL held the collection of Erpenius. Would it be possible to have an overview blog post on the collection and its contents?

Dear Roger,

Many thanks for your interest. A new catalogue of the whole of the Erpenius collection is in preparation. In the meantime, if you have particular questions, please do contact us at mss@lib.cam.ac.uk.

Best wishes,

Suzanne Paul

Keeper of Rare Books and Early MSS, CUL