Zodiac Men and Talking Books: two new online exhibitions

This guest post is by Sara Manlowe and Eleanor Watson, MA students from the Universities of Bristol and York respectively.

Earlier this year, Sara and Eleanor participated in a placement on the Curious Cures in Cambridge Libraries project at Cambridge University Library. Their brief was to design an online exhibition of manuscripts, drawing on examples from the project, in order to share these materials with a broader audience. At the end of their placements, they presented their finished exhibitions to a gathering of project and UL staff.

Their online exhibitions are now online and available for everyone to view. They provide excellent introductions to a wide range of medieval medical manuscripts, their production, contents and use — and Sara and Eleanor have written the following by way of an introduction to their work.

To view Sara’s exhibition, click here: The Zodiac Figure in Medieval Medicine

To view Eleanor’s exhibition, click here: If these books could talk

Sara Manlowe

I came to the Cambridge University Library’s Curious Cures project from my Master’s degree at the University of Bristol. My aim was to use the digitised medical manuscripts to create a virtual exhibition that would be engaging to scholars and non-scholars alike, to get audiences interested in the Curious Cures project by helping them to discover the manuscripts it is covering, and to give them the contextual knowledge they need to study and understand them.

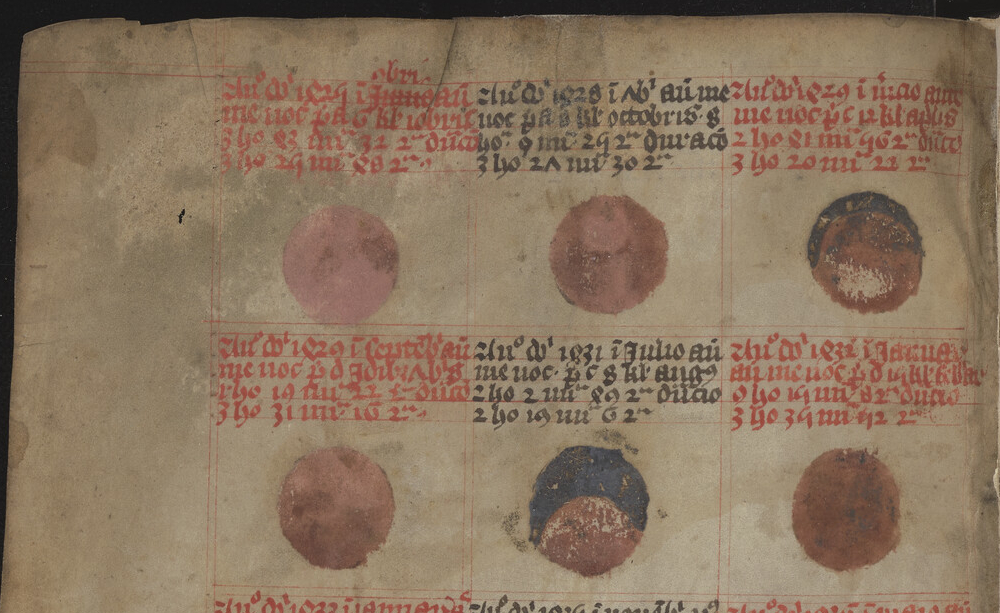

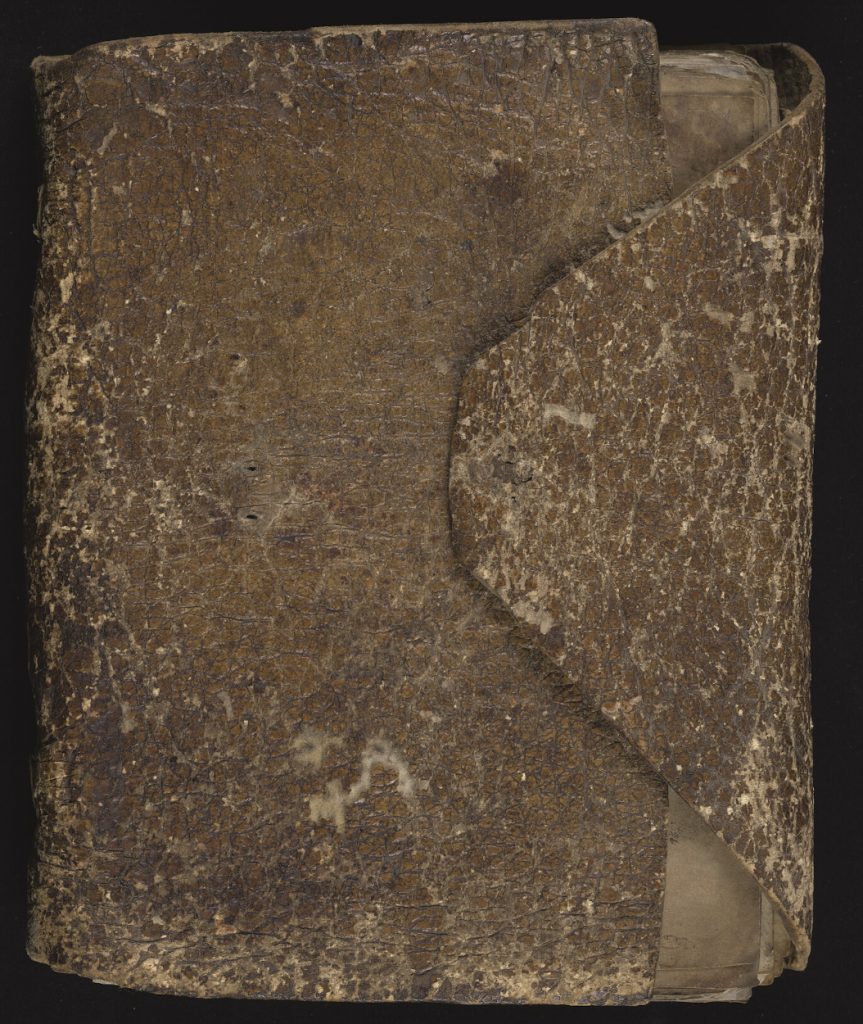

Cambridge, University Library, MS Add. 3303(3)

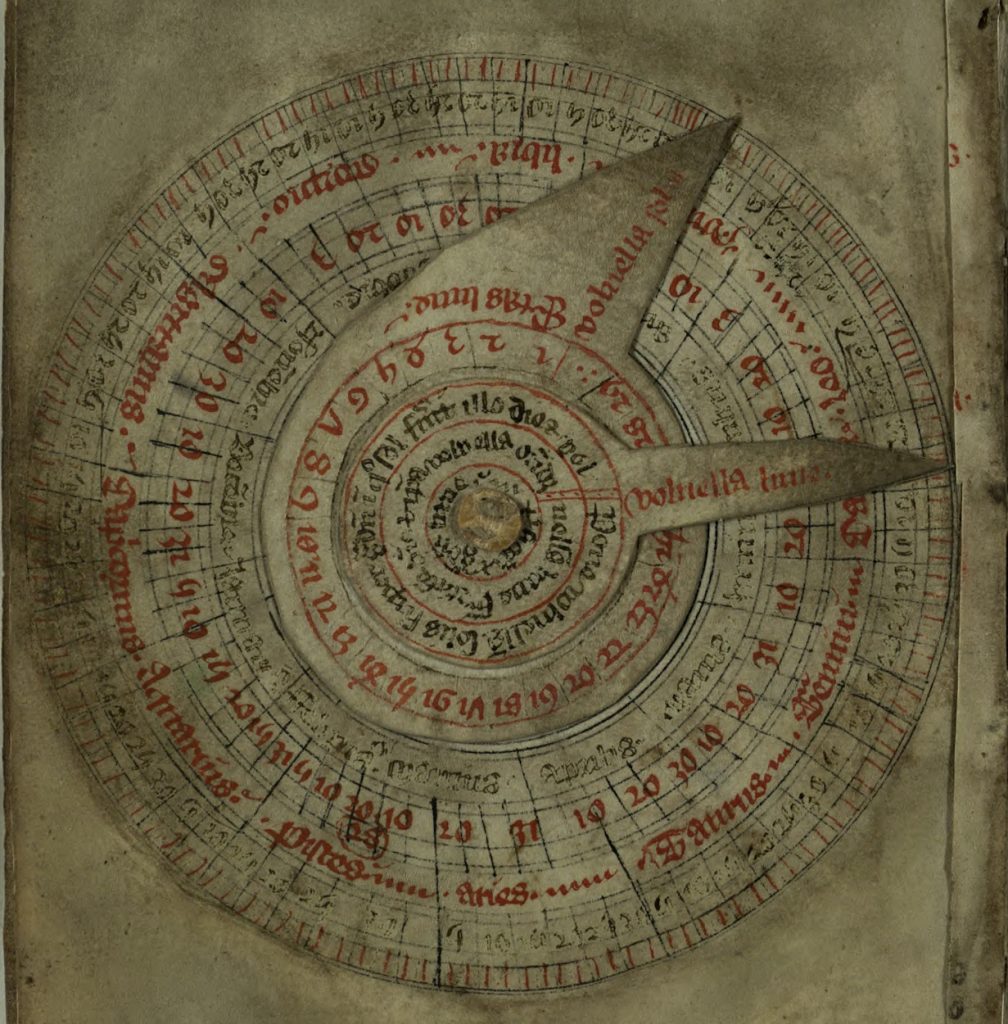

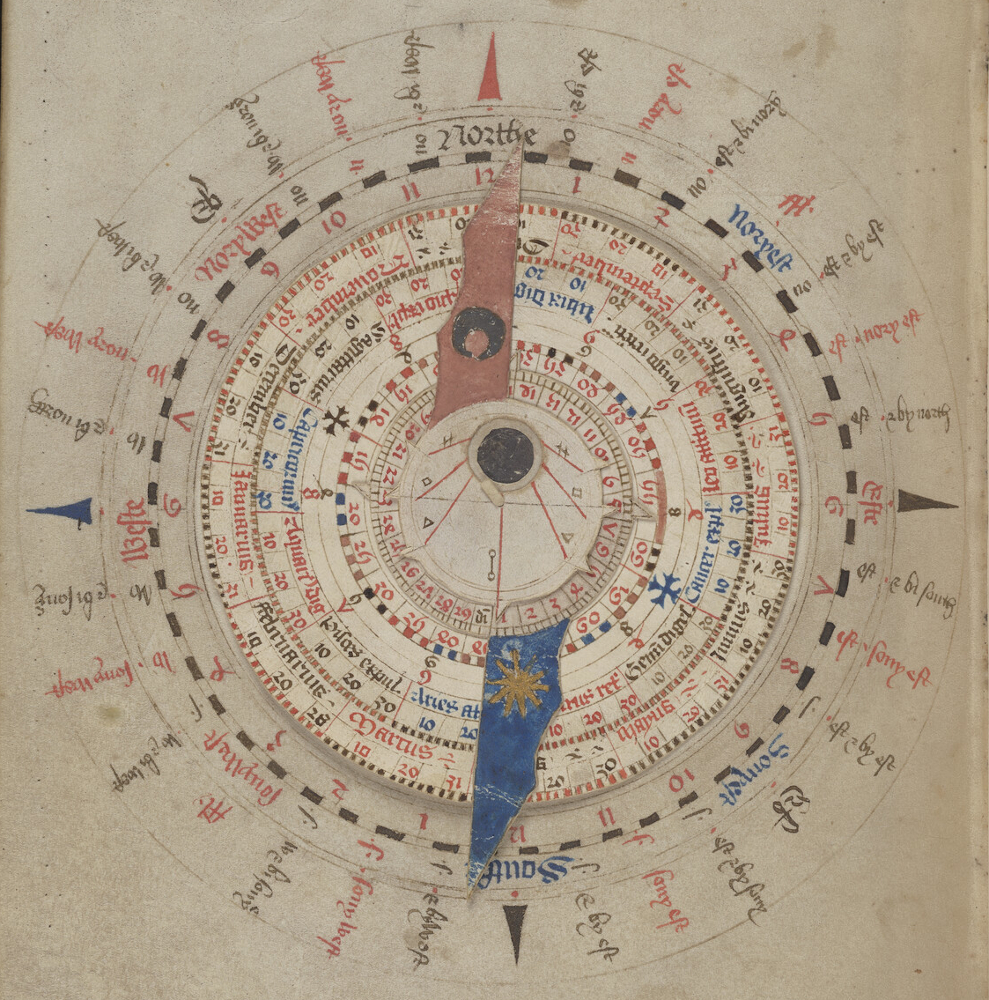

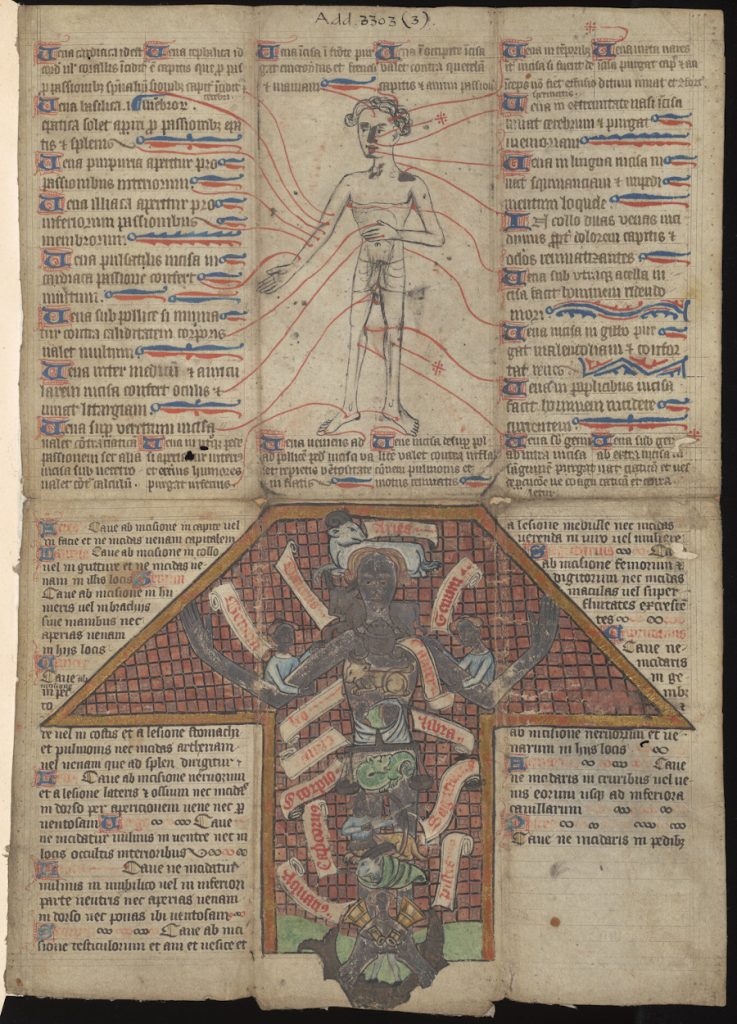

My exhibition is about a type of image known as the Zodiac Figure, through which I discuss the wider role that astrology played in medieval medicine. I arrived at this idea through — to my mind — some of the most visually striking imagery scattered across the Curious Cures manuscripts: astrological charts laid out in neat lines, red and black crescents of lunar eclipses, and stoic-looking Vein Men offering their limbs to the reader’s scrutiny.

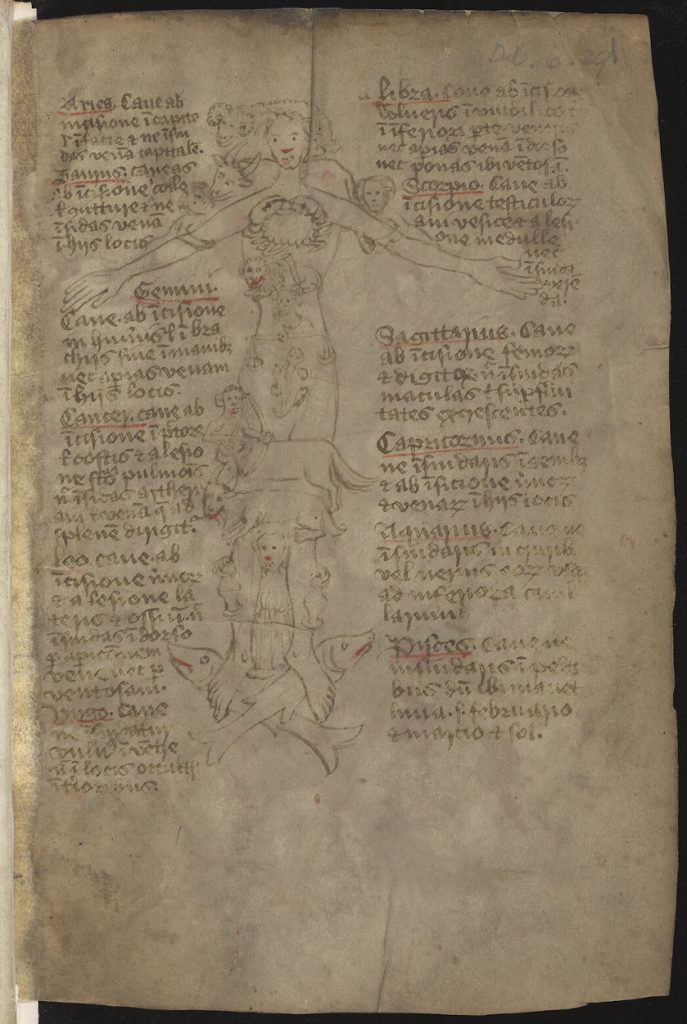

Cambridge, University Library, MS Dd.6.29, f. 126v

Astrology was a common theme in these images. I realized this was the perfect subject for an exhibition — astrology is practiced to this day, across the world — and I aimed to use a modern reader’s general knowledge of astrology as a way of making wider topics of medieval cosmology accessible. The idea of a relationship between celestial bodies and our own physical bodies would therefore be, if not always wholly credible, then at least comprehensible, and indicative of the mathematical and observational systems that were embedded in medieval astrological medical practice.

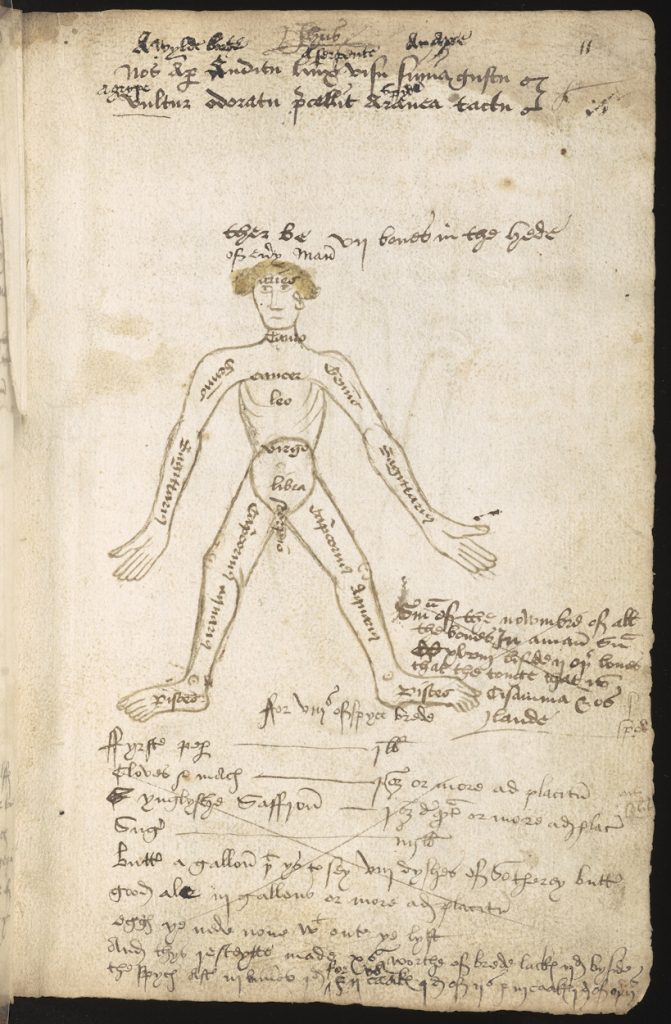

Cambridge, University Library, MS Ee.1.15, f. 11r

Cambridge, University Library, MS Dd.6.29, f. 1r

The Zodiac Figure was a fitting centerpiece: not only is it visually appealing, but it is also symbolic of the correspondence between the microcosm of the human body and the larger, celestial macrocosm — a concept that originated in antiquity and persisted in medieval thought. The images of the Zodiac Figure provided the ideal framework through which to discuss the astrological texts I had found, as well as the Galenic, humoral theory that informs the accompanying treatises. In addition, the Zodiac Figure’s twelve body parts provided me with a ready-made structure I could use to present twelve different medical recipes.

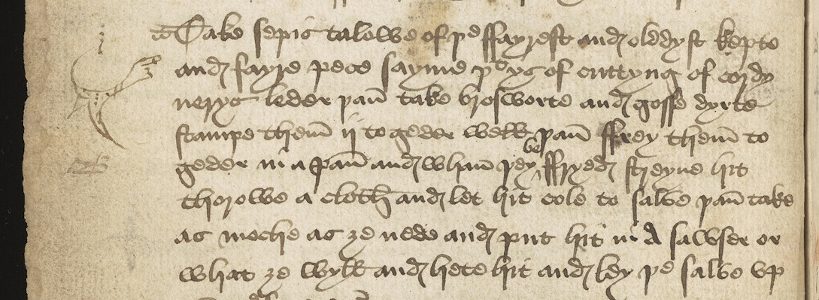

Since my intended audience was not necessarily academic, but rather people generally interested in astrology and history, most of the manuscripts I selected for the exhibition, and all of the recipes, are in Middle English. Readers can look from the transcribed, modernised recipe on one side, to the original, handwritten recipe on the other. This juxtaposition invites the viewer, armed with the knowledge of what they are seeing, to perform the task of the medievalist, and to attempt to read recipes written as early as the thirteenth century. I wanted viewers to leave the exhibition with the sense that they too could interact with a manuscript; I wanted them to experience that peculiar intimacy of being able to read a text that someone wrote by hand, hundreds of years ago.

Of course, there will always be people who click on something with ‘medieval medicine’ in the title out of the morbid desire to see something disgusting — and I did include a recipe that involves eating earth worms mashed with wine and sugar! But I hope, above all else, that readers leave my exhibition with the knowledge that while these practices may seem ignorant, or entirely random on their own, they are facets of a wider, compelling cosmology that followed its own particular logic, and which still has its echoes in today’s world.

To view Sara’s exhibition, click here: The Zodiac Figure in Medieval Medicine

Eleanor Watson

‘Oh, and don’t forget to wash your hands afterwards.’ As anxious as I had been to handle the medical manuscripts of the Curious Cures project in a safe and correct way, this final stage hadn’t occurred to me. The delicate nature of books of this age was evident, I knew that changes in light, temperature and humidity could all damage them, let alone my own potential human error. How, then, could handling the pieces of this collection possibly harm me?

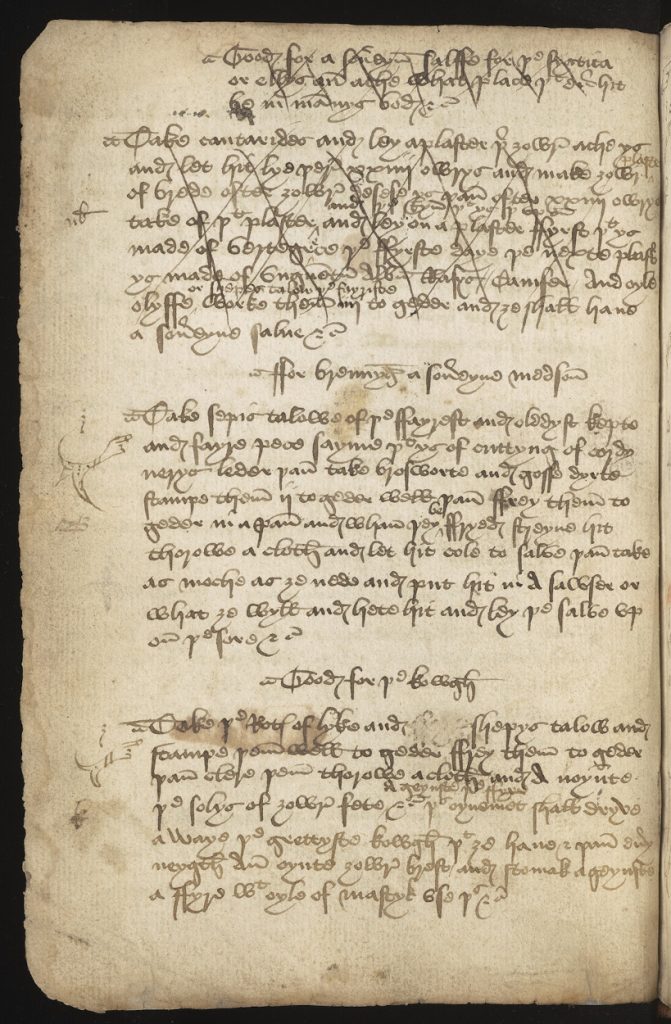

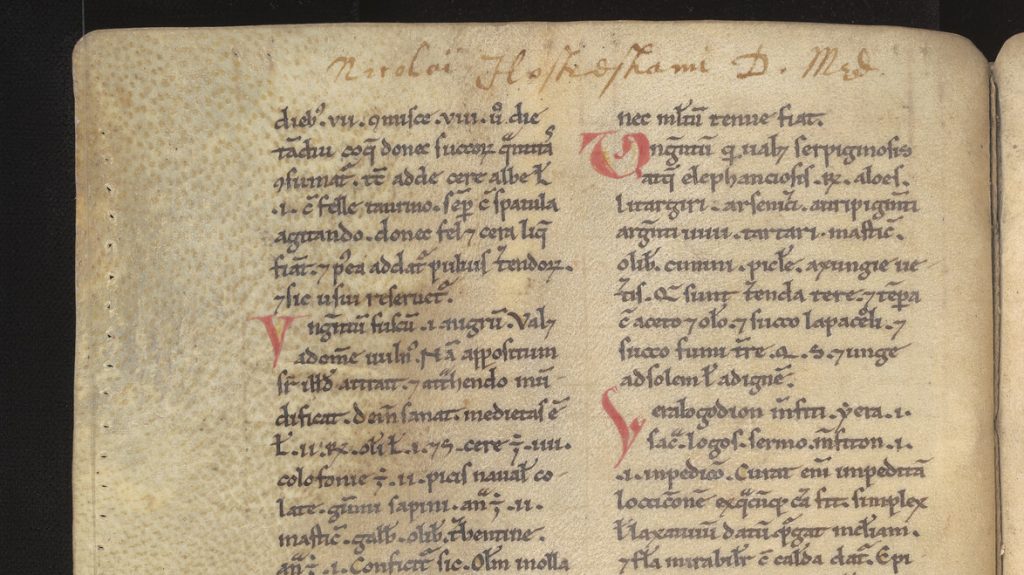

Cambridge, University Library, MS Ee.1.15, f. 17v

One glance at the various uncertain stains that blemish bloodletting instructions, tracts on urine analysis and recipes for treating the plague was all the answer I needed. Strewn across the pages of these recipes are compelling signs of their use: the scrawl of annotations, the striking through of some remedies, and detailed drawings of manicules, which all point to stories of trials and testing, failures and successes. Looking beyond the text at the shapes and textures, I was reminded of the many hands that had held these books, that had made them and used them. This sense of humanity struck me as an easily accessible way for the public to find a connection with the project and its manuscripts.

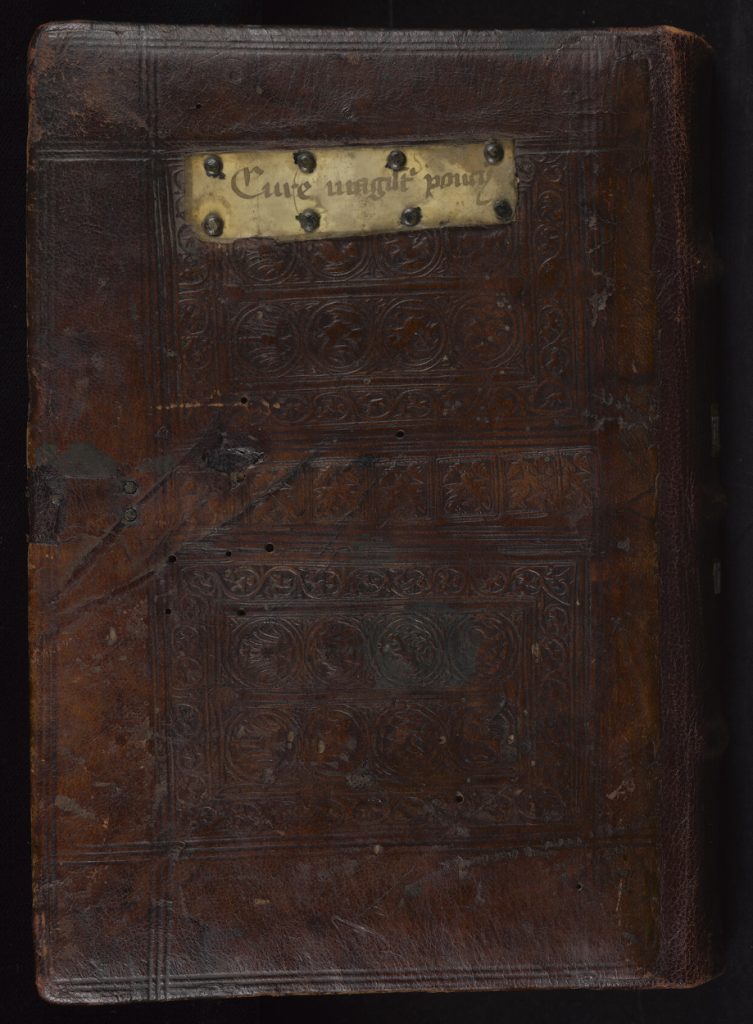

Cambridge, Gonville & Caius College, MS 190/223

Cambridge, Gonville & Caius College, MS 213/228

Cambridge, University Library, MS Add. 9309

Cambridge, Gonville & Caius, MS 379/599

Cambridge, University Library, MS Add. 6865

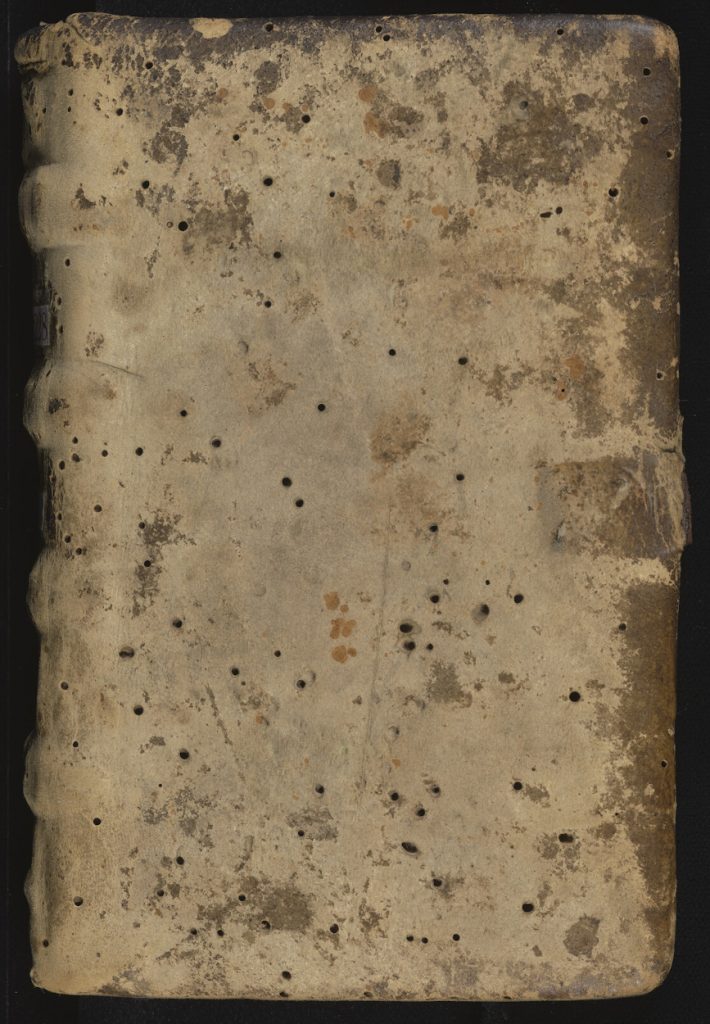

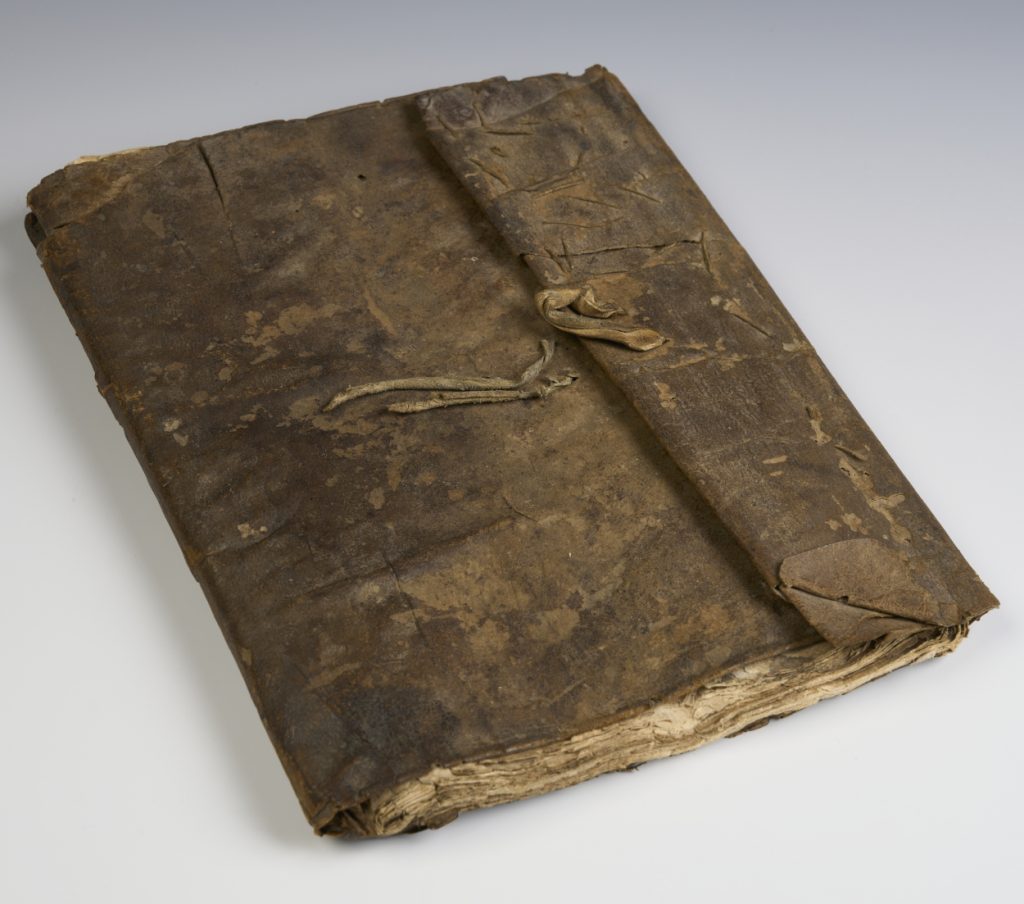

Whilst some of the project’s manuscripts spent their lives in libraries and would likely never have been glimpsed by a nervous patient, there are many that appear to have been close witnesses to medical practice. These tiny handbooks and informal notebooks stand alongside the more austere volumes that contained the kinds of medicine taught in medieval universities. When we look closely at them, we can see the flaking surface of medieval leather coverings, or the follicle patterns that betray the parchment’s animal origins. As onlookers to medieval medical practice, these books have a fascinating story to tell. Finding a way to share these tales — to give a public audience the knowledge to understand the signs of life in these inanimate objects — became my goal: and so, If These Books Could Talk was born!

Cambridge, University Library, MS Add. 6865, f. 78v

The exhibition guides the viewer through the structure of some of these manuscripts. I wanted first to encapsulate their construction, from the raw materials to the processes undertaken to turn them from bloody hides to the taut ivory-coloured leaves that hold this medical knowledge.

Representing these objects as tools as well as texts was of equal importance, so I showcased such features as the fascinating volvelles that can be found in several of the manuscripts. The parchment wheels of this diagnostic instrument would be turned to calculate astrological information necessary for medical treatment and determine the appropriate time to administer a medicine. Whose hand last turned this volvelle and to whom was the prognosis read to? Asking how these books were used in practice truly brought them alive.

On our last visit to the library, Sara and I presented our exhibitions to the team alongside a display of manuscripts organised by Clarck Drieshen and Sarah Gilbert, the Curious Cures project cataloguers. We were told how one of the manuscripts seemed to have a distinctive smell upon its release from archival captivity: had it not been opened for a very, very long time? Each of us brought our nose as close as possible to the gutter of the book, to see if the scent still remained. These books’ organic qualities are evident to all who handle them and are exactly what make them so beautiful. Perhaps, in the future, we will be able to understand the stories behind the stains we can still see in these volumes. Only two years ago, through groundbreaking biomolecular analysis, traces of bodily fluids were found on a medieval birthing girdle made of parchment, indicating that it had been worn and used during a woman’s labour. The possibilities of the Curious Cures project, and the discoveries that may follow from its completion, are plentiful and exciting.

For now, I encourage you to feast your eyes upon the detail of the images being produced by the project. Zoom in as far as the viewer will take you. From a safe digital distance, we can read these manuscripts and bring them back to life. However — be warned — the digital images are so detailed that, even though you’re looking through a screen, you may still have the urge to wash your hands.

To view Eleanor’s exhibition, click here: If these books could talk