The legacy of Francis Jenkinson: a symposium

‘The care of books is a difficult business’, remarked Francis Jenkinson in his presidential address to the annual meeting of the Library Association in 1905 — and that business was but one of many responsibilities that Jenkinson shouldered during his long service as Cambridge University Librarian from 1889 until his death in 1923. Over this period, the Library’s holdings expanded considerably, with the arrival of some 200,000 medieval Jewish manuscript fragments from the Cairo Genizah, as well as important collections from China, Japan and South Asia, amongst others — an area of Jenkinson’s librarianship in need of further study. Important additions were also made to the Library’s collections of western medieval manuscripts and early printed books through purchases, gifts and legacies (in particular from Samuel Sandars), in which processes Jenkinson played an important role (not least as a donor himself). Jenkinson’s time in office also coincided with significant changes in the university landscape, in particular the growth in numbers of female students, and he was involved in contemporary debates about both their admission as readers at the University Library and their admission to degrees. His intellectual interests were also highly varied, with entomology and archaeology featuring alongside bibliographical study and analysis of early printing, the editing of Latin poetry and the collecting of ephemera relating to the Great War.

A symposium is being held at Cambridge University Library on 6th October 2023 in Jenkinson’s memory, in the centenary year of his death. After his passing, contemporaries and colleagues remembered him as ‘a positive and powerful force in Cambridge scholarship’, and ‘one who, primarily a scholar and researcher himself, unselfishly put all he knew at the disposal of any worthy seeker’ — but what is Jenkinson’s legacy today? Taking inspiration from a similar event held in 2017 in memory of Henry Bradshaw (University Librarian, 1867-1886), of whom Jenkinson was a disciple, this event seeks to bring together researchers, curators and library professionals whose work has touched upon Jenkinson’s scholarly, professional or personal life in some way, to provide opportunities for the discussion and critical assessment of his contribution, and for reflection upon how this might inform the future development and direction of libraries, their collections and their staff.

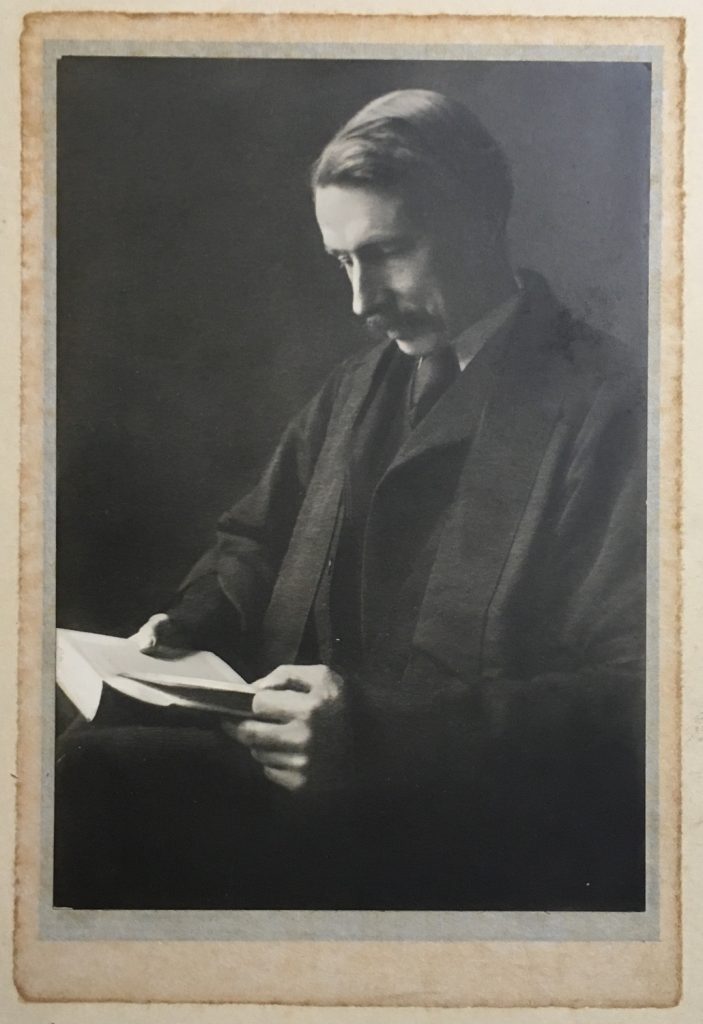

Eight speakers will be presenting on a range of topics, reflecting and arising from Jenkinson’s many scholarly achievements and interests (see below for a summary programme). There will also be a display of manuscripts and printed books relating to Jenkinson and the day’s proceedings. Refreshments and lunch will be provided. A drinks reception will be held at the end of the day on the landing outside the Librarian’s office, permitting attendees to view the portrait of Jenkinson by John Singer Sargent.

Registration is £40. Thanks to the generosity of the Bibliographical Society of London, ten places for postgraduate or undergraduate students are available at a reduced rate of £15.

To reserve your place, go to the University of Cambridge’s Online Booking System.

Summary programme (subject to change):

9.15-9.55 – Registration

09.55-10.00 – Welcome

10.00-10.30 – Ann Kennedy-Smith, Burn after reading: exploring Francis Jenkinson’s and Ida Darwin’s letters at Cambridge University Library (1891–1901)

10.30-11.00 – Jill Whitelock, Fly-leaves: books, insects and Francis Jenkinson’s ‘natural history method’

11.00-11.30 – Tea break

11.30-12.00 – James Freeman, The disbinding of Codex Bezae: a tale of unintended consequences

12.00-12.30 – Caylin Smith, The care of digital books is a difficult business: contemporary collecting and the moving target of digital formats

12.30-13.15 – Display of Jenkinsoniana curated by Liam Sims (in the Rare Book Reading Room)

13.15-14.00 – Lunch

14.00-14.30 – Arnold Hunt, The attraction of opposites: Francis Jenkinson and Edward Gordon Duff

14.30-15.00 – Bill Stoneman, Francis Jenkinson and George Dunn of Woolley Hall, near Maidenhead

15.30-16.00 – Tea break

16.00-16.30 – Nick Posegay, Francis Jenkinson and the Cairo Genizah collection

16.30-17.00 – Marie Turner, Scraps of library history: Francis Jenkinson and the collection(s) of fragments of western medieval manuscripts

17.00-17.30 – Drinks reception and portrait viewing on Librarian’s landing

Abstracts:

Ann Kennedy-Smith, Burn after reading: exploring Francis Jenkinson’s and Ida Darwin’s letters at Cambridge University Library (1891-1901)

This paper considers Francis Jenkinson’s long friendship with Ida Darwin (née Farrer) which began after Ida’s marriage to Horace Darwin in 1880. Jenkinson gave her Greek lessons, and they discovered a shared passion for music and gardening; in 1887 she became close to his wife Marian (née Wetton). After Marian’s tragic death, Ida Darwin became his confidante. She was one of the few people who knew of his secret engagement to Mildred Wetton and his plans to give up his work as University Librarian and move abroad so that they could marry.

Francis Jenkinson’s letters to Ida Darwin are revealing in their frankness and conviction, and show the conflict he felt between his public duty as University Librarian and his private happiness. Their correspondence also offers insights into the wider debates concerning compulsory Greek and women’s degrees at the University of Cambridge in the 1890s.

Jill Whitelock, Fly-leaves: books, insects and Francis Jenkinson’s ‘natural history method’

Natural history was one of Francis Jenkinson’s passions – insects as well as books are woven throughout his life and career. In 1876, four days before his twenty-third birthday, he climbed the Wren Library in pursuit of a Camberwell Beauty. A month before he died, his Under Librarian Charles Sayle wrote to him in hospital, describing how a member of staff had brought a dead dragonfly into the Library: ‘I sent him off with Lucas’s book on Odonata(?)’. Jenkinson’s first University post was Curator of Insects at the Museum of Zoology (1878–79), twelve years before he became Librarian, and his collection of insects went to the Museum after his death. At home, he had a Fly Room, and he brought the same eye for detail and meticulous, systematic arrangement to his beloved pinned collection of Diptera that he brought to the Library’s books. In librarianship, he was Henry Bradshaw’s pupil, who as Librarian from 1867–86 had instigated the so-called ‘natural history method’ for the arrangement of the Library’s collection of incunabula, ordering books by country, town and printer to produce a ‘typographical museum’ that in some way resembled the taxonomic ordering of very different ‘type specimens’ in the natural history museums of the day. Bradshaw himself learned from his friend and entomologist George Robert Crotch (1842–1874), who briefly worked at the Library and whose outstanding collection of ladybirds is also at the Museum of Zoology. In this paper, I explore Jenkinson as entomologist and librarian, in the context of the connected collections and collectors of nineteenth and early twentieth-century Cambridge.

James Freeman, The disbinding of Codex Bezae: a tale of unintended consequences

What principles guide the care and curation of historic collections — and how have these developed since Francis Jenkinson’s time?

Codex Bezae — a late 4th / early 5th century fragmentary copy of the New Testament and Acts of the Apostles — is one of the great treasures of Cambridge University Library, and is named after Theodore Beza (1519-1605), the Swiss Calvinist theologian who donated this ‘antique novelty’ in 1581. Three centuries later, on 28 April 1897, the Library Syndics authorised Francis Jenkinson to have Codex Bezae disbound (apparently for the second time that century), in order that it could be photographed. ‘A facsimile was printed in 1899,’ wrote David Parker, concluding, ‘Such is the history of this manuscript.’

A box of papers kept with the manuscript suggests otherwise. Lying unaccessioned in the Library for more than a century and containing more than is suggested by its label — ‘Codex Bezae: Binder’s notes’ — its contents reveal a further chapter in the story of this important manuscript. They shed light on the decisions (or lack of them) that left Codex Bezae disbound for 68 years, documenting how the manuscript’s leaves were stored, handled and displayed (often for long periods). Together with other unpublished records, these papers illustrate Jenkinson’s often commendable but sometimes over-cautious approach to the care of the Library’s western medieval manuscripts. They also confirm the value inherent in documenting and preserving records of curatorial decision-making: both for the future curation and conservation of manuscripts, and to aid researchers’ proper understanding of the form in which they encounter them.

Caylin Smith, The care of digital books is a difficult business: contemporary collecting and the moving target of digital formats

On the acquisition of books under the UK’s Copyright Act (later, the Legal Deposit Libraries Act 2003), Francis Jenkinson reflected: ‘When we have succeeded in acquiring our supply of copyright books, our work is not done. They form a nucleus to which, it seems to me, we are bound to spend every penny we can in adding other books, both old and new.’

The acquisition of books created in digital formats long outdates Jenkinson’s tenure as Cambridge University Librarian; he could not have foreseen both the possibilities and impact digital has had — and continues to have — on publishing and the creation of books. Nevertheless, his words still resonate with the present and challenges around contemporary collection development and management of books created in digital formats.

One example that throws established characteristics of a book into question are digital publications that are created using mobile and web technologies that offer creators innovative ways to explore narrative and non-narrative genres. A selection of UK-published web-based works have already been collected under the UK’s Non-print Legal Deposit Regulations using web archiving tools and can be accessed with the UK Web Archive.

This presentation expounds on the topic of how the care of books is not time-specific but instead is a challenge that spans the continual evolution of book publishing, as collecting institutions must care for the books they acquire, both old and new, now and over time.

Arnold Hunt, The attraction of opposites: Francis Jenkinson and Edward Gordon Duff

The friendship between Jenkinson and Duff was lifelong, beginning in 1887 when the two men first met, and only brought to an end by Jenkinson’s death in 1923. Their letters, now in Cambridge University Library, were described by H.F. Stewart in his biography of Jenkinson as ‘a correspondence of incomparable value scientifically, and proving to those who need proof, how rich in human interest the dry study of bibliography can be’. This paper will survey the correspondence and discuss what it reveals about the contrasting personalities of these two very dissimilar men.

Bill Stoneman, Francis Jenkinson and George Dunn of Woolley Hall, near Maidenhead

On the 29th of July 1923, the day before his official retirement as Cambridge University Librarian, Francis Jenkinson handed over the manuscript of his last published work, A List of the Incunabula collected by George Dunn arranged to illustrate the History of Printing. It was published posthumously as Supplement No. 3 to The Bibliographical Society’s Transactions later the same year. It includes a brief Introduction by Alfred W. Pollard and an anonymous obituary for Dunn written by Sydney Cockerell and reprinted from The Times of 11 March 1912 and an obituary for Jenkinson by H.F. Stewart and reprinted from the Cambridge Review from 26 October 1923.

One hundred years after its publication this work might seem to be a slightly odd and perhaps irrelevant memorial to the author and the collector. Was there really much interest or scholarly potential in the re-arrangement of a portion of a collection which had first appeared at auction a decade earlier? This paper explores the background to Jenkinson’s last publication, including the history of such publications, their function in later scholarly works and the role of such private collectors in modern public research libraries.

Nick Posegay, Francis Jenkinson and the Cairo Genizah collection

In early 1897, Solomon Schechter, the Cambridge Reader in Rabbinics, shipped several crates of medieval Egyptian manuscripts from Cairo to Cambridge. These manuscripts would become known as the ‘Cairo Genizah’, and they would soon go on to redefine the entire history of the Middle East after 1000 CE, but for the moment they were still a secret. The academically territorial Schechter knew this, so he entreated Francis Jenkinson at CUL (Cambridge University Library), ‘The MSS will probably belong soon to your library…but the boxes must not be opened before I have returned.’ Jenkinson agreed, and over the next five years he became the primary liaison between Schechter and CUL as they organised the new ‘Taylor-Schechter Collection’ of Hebrew and Arabic manuscripts. From their correspondence and diaries, we know that, despite a lack of linguistic expertise, Jenkinson advocated for and assisted in Genizah research while moderating some of Schechter’s more erratic, non-bibliophilic tendencies.

In 1902, Schechter left Cambridge and care of the Taylor-Schechter Collection fell to Ernest Worman, a part-time librarian who was a friend of Jenkinson and an assistant to Schechter. Worman spent 1906-1908 cataloguing the collection, but he died suddenly in 1909, leaving no-one besides Jenkinson who was still connected to Schechter’s work at CUL. The Syndics never appointed a replacement for Worman, and after Jenkinson’s own death in 1923, most CUL librarians seemed to accept that all the valuable Genizah manuscripts had already been identified. They closed the Genizah research room and exiled the unconserved collection to permanent storage on the seventh floor. A century later, Genizah research has been revived and Jenkinson’s legacy is as relevant as ever.

Marie Turner, Scraps of library history: Francis Jenkinson and the collection(s) of fragments of western medieval manuscripts

Abstract forthcoming.

Thank you very much for orgainizing this very relevant symposium!

Kind regards,

Simon F Dietlmeier