The Autograph of al-Khaṭīb al-Tibrīzī (d. 502/1109): A Very Early Source for the Poetry of al-Maʿarrī.

This post is by the inaugural Oschinsky Research Associate, Dr James White. James is working with a core group of forty Arabic and Persian manuscripts which date from the thirteenth century through to the sixteenth century, held in the University Library and the Cambridge colleges and museums. The aim of his research is to map the intertextual connections (i.e. instances of text reuse) between these manuscripts, and show how communities of authors, scribes and readers active across North Africa, the Middle East and South Asia were connected through circulation prior to the nineteenth century.

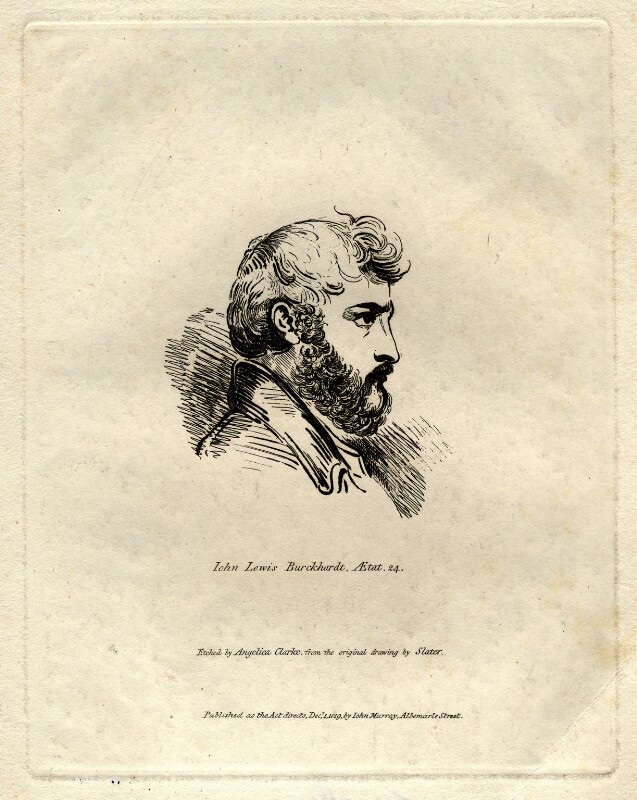

Among the many important Arabic manuscripts that are held in Cambridge University Library, those prefixed ‘Qq.’, forming the collection of the Swiss adventurer Johann Ludwig (anglicized to ‘John Lewis’) Burckhardt (1784-1817), deserve special mention. Burckhardt travelled extensively in the Levant, Egypt and the Arabian Peninsula between 1809 and his sudden, early death in 1817, developing a remarkable degree of fluency in Arabic and a profound knowledge of medieval and early modern Arabic texts.[i] He started purchasing Arabic manuscripts very quickly after arriving in Syria, and continued his collecting activities after moving to Egypt, regularly shipping trunks full of the books which came into his possession back to England.[ii] His collection concentrates on adab texts (works of premodern literary culture), spanning fields such as historiography, poetry, literary criticism, biography, geography, genealogy, and rhetoric. There is a particular focus on philological works, such as commentaries which unpack and explain the language of classical Arabic poetry.

One of the most striking aspects of Burckhardt’s collection is the value of the manuscripts for the study of textual history. It is not simply that the texts that are contained in the volumes are rare or important, but that the particular copies which Burckhardt acquired are often significant witnesses, and it would seem that he deliberately sought out the old and the accurate. Many of the manuscripts are exceptional because they are early, including Qq. 285, a volume containing The Book of the Long-Lived (Kitāb al-muʿammarīn) and The Book of Advice (Kitāb al-waṣāyā), both by Abū Ḥātim al-Sijistānī (d. 255/869), which is dated 428/1036 and is CUL’s oldest Islamic codex on paper.[iii] Two beautifully calligraphed and vowelled copies of the Ḥamāsa, Abū Tammām’s (d. ca. 232/845) famous anthology of poetry (Qq. 113 and Qq. 296), date to the twelfth century, making them among the earliest known surviving manuscripts of this text. While undated, Qq. 212, a copy of al-Khaṭīb al-Tibrīzī’s (d. 502/1109) commentary on the Muʿallaqāt (the canonical poems of the pre-Islamic Arabic corpus), is very precise, and formed the basis of Charles Lyall’s 1894 edition of the poems.[iv]

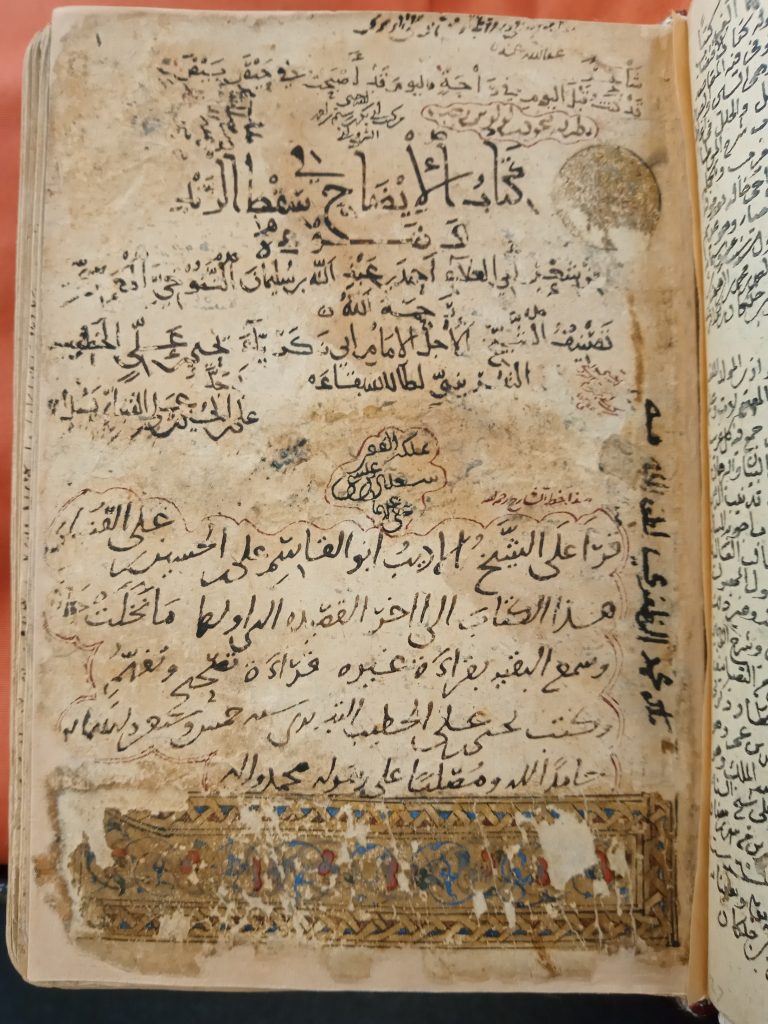

To this list should be added another manuscript whose importance has thus far been ignored. Qq. 115 is a copy of al-Khaṭīb al-Tibrīzī’s commentary on the youthful verse of his teacher, Abū l-ʿAlāʾ al-Maʿarrī (d. 449/1058), one of the greatest poets of Arabic who ever lived. E.G. Browne’s entry on this manuscript in his handlist of 1900 – the most recent catalogue of this part of the CUL Arabic collection – runs as follows:

The Īḍāḥ fī Siqṭiʾz-Zand, or Commentary on Abu’l-ʿAlā al-Maʿarrī’s poem called Siqṭu’z-Zand (q.v.) by Shaykh Abū Zakariyya Yaḥyā b. ʿAlī al-Khaṭīb al-Tabrīzī…[Ff. 252+6 or 7 at beginning, of 19.5 x 13.3 c. and 23 ll.; fair naskh, pointed; no colophon, but at the end several ijāzas dated A.H. 617, 622, 626].

The manuscript does indeed contain several ijāzas, or certificates of transmission, which were appended to it in 617/1220-21, 622/1225 and 626/1227-28. However, the text itself was not copied in the thirteenth century, but rather in the eleventh. Perhaps Browne simply did not have the time to inspect Qq. 115 and copied his description from Preston’s 1853 catalogue of the Burckhardt collection, which is similarly inaccurate.[v] Or perhaps he missed the title page. In any case, f. 1a forces a reconsideration of the manuscript’s dating.

The page is mostly copied in a fine and very old scribal naskh, naming the text as:

كتاب الإيضاح في سقط الزند

وضوءه

في شعر أبي العلاء أحمد بن عبد الله بن سليمان التنوخي المعري

رحمه الله

تصنيف الشيخ الأجل الإمام أبي زكرياء يحيي علي الخطيب

التبريزي أطال الله بقاءه

The Book that Illuminates the Spark of the Firestick

and its Light

On the poetry of Abū l-ʿAlāʾ Aḥmad b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Sulaymān al-Tanūkhī al-Maʿarrī

May God have mercy on him.

The composition of the illustrious shaykh, the imam Abū Zakariyyāʾ Yaḥyā al-Khaṭīb

al-Tibrīzī, may God prolong his life.

Contrasting with this neat scribal hand, a spidery, professorial one has noted further down the page:

قرأ علي الشيخ الأديب أبو القاسم علي بن الحسين بن علي القتباي

هذا الكتاب إلى آخر القصيدة التي أولها ما نخلت جارتنا

وسمعت البقية بقراءة غيره قراءة تصحيح وتفهم

وكتب يحيي بن علي الخطيب التبريزي سنة خمس وسبعين وأربعمأية

حامداً لله ومصلياً على رسوله محمد وآله

The shaykh and man of letters Abū l-Qāsim ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn b. ʿAlī al-Qutbāy read

this book aloud to me up to the end of the ode which begins ‘Our neighbour did not reserve [her love for me alone]’

and I listened to the rest of it in another person’s emendatory and explanatory recitation.

Yaḥyā b. ʿAlī al-Khaṭīb al-Tibrīzī wrote [this] in the year 475[/1082-83],

praising God, and praying for His Prophet Muḥammad and [His Prophet’s] family.

An additional folio, bound into the manuscript between f. 158 and f.159, is annotated in the hand of the scribe as a ‘gift’ (tuḥfa) from al-Khaṭīb al-Tibrīzī, and consists of a gloss in al-Tibrīzī’s hand on the meaning of the place name Jilliq. Collectively, this folio and the title page tell us that the manuscript was copied by a professional editor-scribe, al-Qutbāy, and that the text was approved by the commentator, al-Khaṭīb al-Tibrīzī, in 475/1082-83. This makes Qq. 115 one of the oldest Arabic codices on paper in the CUL collection, and a significant source for the textual history of al-Maʿarrī’s Siqṭ al-zand. As al-Khaṭīb al-Tibrīzī was al-Maʿarrī’s student, and had spent time with the poet, his edition of Siqṭ al-zand would have been regarded in its own time as an accurate reflection of al-Maʿarrī’s text.[vi] Over nine hundred years later, the manuscript still offers a tangible physical link to the great poet and his own words.

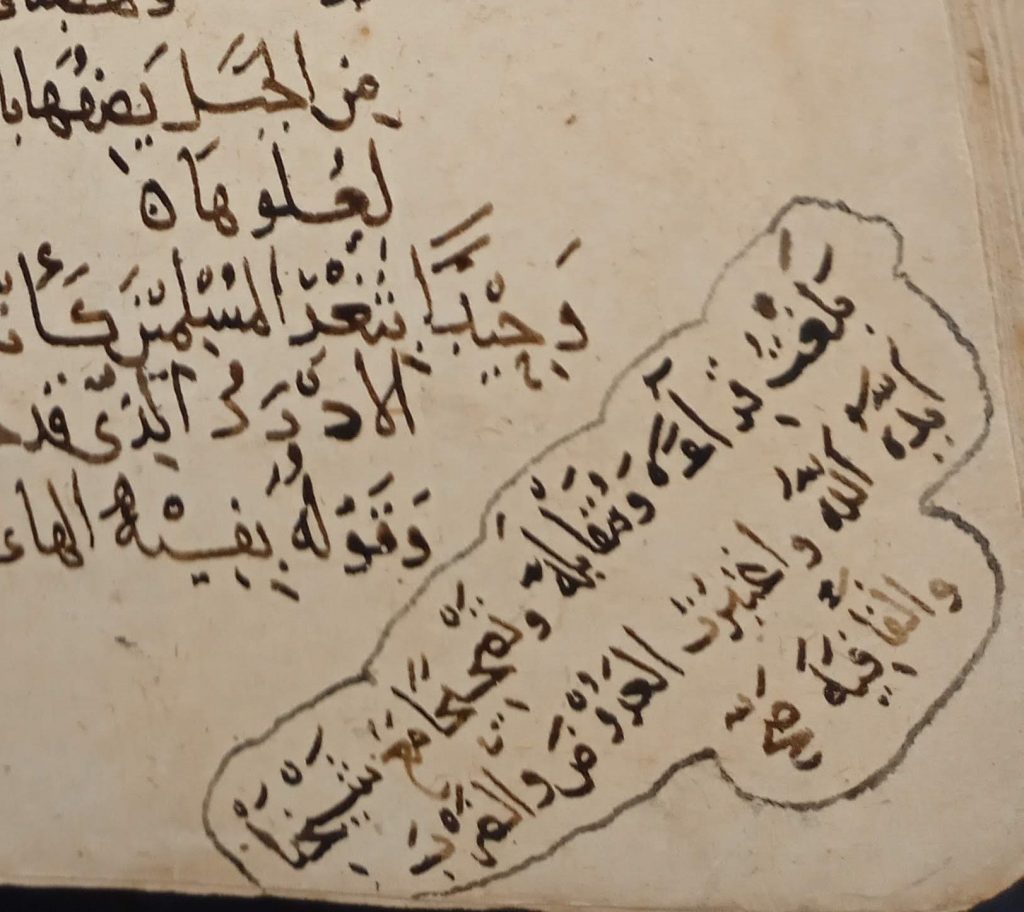

One further reason why Qq. 115 is so precious is that the manuscript is also a model of careful editing and collation. Discounting modern endpapers, the volume can be very neatly collated into twenty-four quinions and one sesternion. No catch words are used. Instead, the editor-scribe repeats the same formula on the b side of the last folio in every quire: ‘I managed to read, collate and edit this with our teacher, may God support him, and I checked the metre, the rhyme, and the last foot of each second hemistich against what had been transmitted’ (balaghtu qirāʾatan wa-muqābalatan wa-taṣḥīḥan maʿa shaykhinā ayyadahu allāhu wa-iʿtabartu l-ʿarūḍa wa-qāfiyata wa-l-ḍarb). This shows that the editor-scribe went to great lengths to ensure the accuracy and the authenticity of his edition, and that he developed processes for ensuring that this accuracy could be retained when the quires were assembled into a physical book. The collation notes also enabled the quires to be kept in check should the codex be rebound at a later date. Furthermore, the scribe placed notes next to many of the individual poems throughout the manuscript, marking them as having been checked with al-Tibrīzī. We can understand the production of the book as an ordered series of exchanges between the editor-scribe and the commentator, so that the codex could be disseminated as a surrogate for attending the study circle of al-Tibrīzī and hearing him lecture.

I hope that this discovery will encourage others to study Qq. 115. The most accurate printed edition of al-Īḍāḥ was brought out over twenty years ago by Fakhr al-Dīn Qabāwah, and depends on another autograph copy of the text, bearing al-Tibrīzī’s signature, which is now held in Istanbul.[vii] Comparing the Istanbul and Cambridge manuscripts may not only provide us with an even more accurate reading of Siqṭ al-zand, but also illuminate more about scholarly culture, book production, and the relationships between authors and scribes in the medieval world.

Finally, I must also point out that this discovery is one rooted in a continuum of scholarship which extends back over the centuries. After I had deciphered the title page of Qq. 115 and realised what I had found, I checked Preston’s catalogue of the Burckhardt collection to see how far back the misidentification went. The copy of Preston’s catalogue which I chose to order was the one formerly owned by the formidable Cambridge bibliographer Henry Bradshaw (d. 1886), who is not generally known as an Arabist.[viii] On finding Preston’s remarks on Qq. 115, I noticed that Bradshaw had laconically annotated the copy with the note “Tabrizi’s handwriting on Title dated 475”. A useful reminder that there is much undiscovered, and discovered then forgotten, to be found on the shelves of CUL.

[i] See Catherine Ansorge, “Study and travel: John Lewis Burckhardt’s Remarkable Journey Traced through Archives and Manuscripts in Cambridge University Library”, Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society 16.3 (2018), 455-86. Burckhardt’s linguistic abilities are exemplified in his book on Egyptian Arabic proverbs, Arabic Proverbs, Or, The Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians: Illustrated from Their Proverbial Sayings Current at Cairo, London: John Murray, 1830.

[ii] Ansorge, “Study and Travel”, 478.

[iii] Ansorge, “Study and Travel”, 480.

[iv] C.J. Lyall, A Commentary on Ten Ancient Arabic Poems: Namely, the Seven Muʿallaḳāt, and Poems by Al-Aʿsha, An-Nābighah, and ʿAbīd Ibn Al-Abras, Calcutta: Asiatic Society of Bengal, 1894.

[v] T. Preston, Catalogus Bibliothecæ Burckhardtianæ: Cum Appendice Librorum Aliorum Orientalium in Bibliotheca Academiæ Cantabrigiensis Asservatorum. Cambridge: The University Press, 1853. See also Carl Brockelmann, History of the Arabic Written Tradition, trans. Joep Lameer (Leiden: Brill, 2016), 1:257 and 1:288-9.

[vi] See R. Sellheim, “al-Tibrīzī”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, eds. P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs <http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_7535>

[vii] al-Tibrīzī, al-Īḍāḥ fī sharḥ Siqṭ al-Zand wa-Ḍawʾih, ed. Fakhr al-Dīn Qabāwah, first printing, Aleppo: Dār al-Qalam al-ʿArabī, 1999.

[viii] Adv.b.77.16.