Translating Persian Tafsir in Aceh: The Oldest Malay “Story of Joseph” at Cambridge University Library

This post is written by Dr Majid Daneshgar who recently completed his Munby fellowship at Cambridge University Library and is now Associate Professor of Area Studies in the Center for Southeast Asian Studies at Kyoto University, Japan.

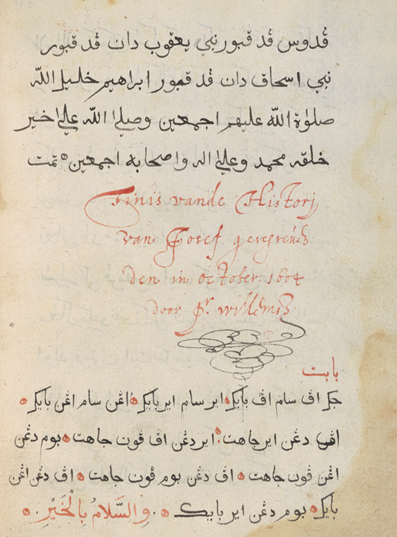

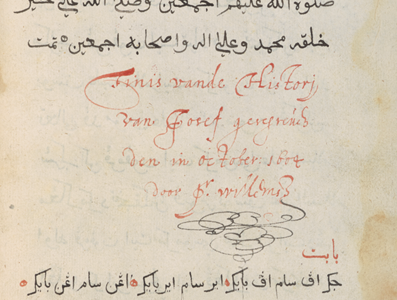

Among the rare Malay-Indonesian manuscripts belonging to Thomas Erpenius (d. 1624), now kept at Cambridge University Library, there is MS Dd.5.37, copied by the Dutch traveller and merchant, Pieter Willemsz van Elbinck (d. 1615) (also known as Peter Floris).[1] It measures 20.5 x 15.7cm and contains 62 folios. It was copied in Aceh, Sumatra in 1604 and includes three treatises, its main part being about the Prophet Yusuf (Joseph) (ff.1-60). The erroneous orthography shows that van Elbinck was still in the early stages of learning Malay Islamic literature.

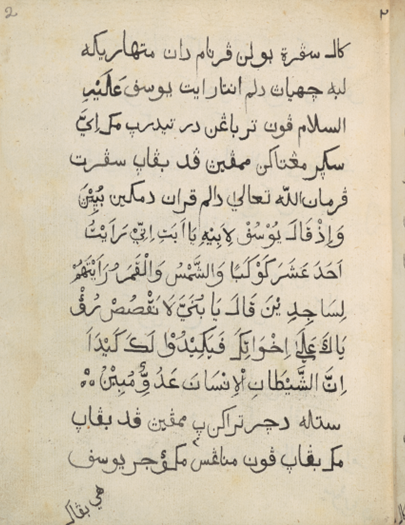

The most striking point about this long treatise is the content and format of the text, which has been considered as an example of “Hikayat” or “Malay Islamic Folk Stories” in former studies.[2] The initial Arabic phrase “هَذَا قِصَّةُ الیُوْسُفْ” (“This is the Story of Joseph”) (fl.1) also prompted earlier scholars to propose this idea. This treatise concerns the Qur’anic Chapter of Yusuf, Q12. The third verse of this chapter describes its genre as a “story”, as well.

It is not surprising that this manuscript was in the possession of Erpenius. He produced the first extant commentary on Q12 in Latin in 1617. He titled his commentary (and translation) “Historia Josephi Patriarchæ”,[3] which was also the title given to MS Dd.5.37 in 1625 before its arrival in Cambridge. Erpenius refers to the Arabic alphabet (“Alphabeti Arabici”) in his introduction and explains variant forms of orthography and spelling for the letters پ (pe) and گ (gaf) used by Tatars, Turks, Persians and Indians (including Malay).[4] Considering that Erpenius printed his Latin commentary in 1617, it may be assumed that he obtained MS Dd.5.37 (and other Malay materials) a few years before its publication date.

While examining Dd.5.37, I noticed that its formation is clearly in contrast to folk stories in which Qur’anic verses contribute marginally just to give more sense to the whole body of the narrative. To clarify the point, one may refer to old sources like the Hikayat Bayan Budiman (‘Tale of the Parrot’), Hikayat Muhammad Hanafiyyah (‘Tale of Muhammad Hanafiyyah’), Hikayat Iskandar Zulkarnain (‘Tale of Iskander Dhu l-Qarnayn’), in which there are a few Qur’anic verses. Even the Hikayat Bulan Berbelah (‘Tale of the Splitting of the Moon’) whose theme is based on Q54 (‘the Moon’) contains few verses in comparison to Dd.5.37. Other folk stories which were used for conversion purposes in Southeast Asia such among others as the Hikayat Musa Munajat (‘Tale of Musa’s Conversation with God’) and Hikayat Raja Jumjumah (‘Tale of King Jumjumah’) are more supplicatory than exegetical, through which readers would gain more information about mystical and theological invocations in Islam.[5]

In this vein, I would draw a distinction between the content of Dd.5.37 and other Malay folk stories. Dd.5.37 does not include all 111 verses of the Yusuf chapter, but it contains more than 20 verses in Arabic and several in Malay translation (without Arabic), which are key phrases in the text and are explained one by one. As Wieringa suggested, the story of Joseph in the Malay-Indonesian world in general, and in Dd.5.37 in particular, acts like a folk story and may have further theological purposes.[6] And this “theological purpose” may refer to its application in missionary activities (e.g., conversion) or in pedagogical circles (e.g., studying Islam). Yet, none of these practicalities should distract us from considering the original nature of the text. Thus, whether it was originally produced as a “commentary” or “folk story” should be as important as the text’s application as a “commentary” or “folk story”. Ignoring the original nature of the Malay text may end up distorting the status of Islam in ancient Southeast Asia. The case of Dd.5.37 is a significant example in highlighting the importance of distinguishing between “textual origin” and “textual usage”.

The structure of Dd.5.37 reveals that it is a select part of a commentary on the Qur’an (tafsir) covering Q12. It contains verses which are explained regularly. Thus it is not surprising that Erpenius owned Dd.5.37 before publishing his own interpretation of Q12.

Now, two questions should be answered about the origin and influence of Dd.5.37:

(a) who is the commentator?

(b) how important is this manuscript?

- The Origin of the Manuscript

Anyone familiar with Qur’anic exegetical literature from the Malay Archipelago will realise that the tone and word arrangement of Dd.5.37 is different from other classical 17th-century Malay commentaries. This suggests that it may well have been influenced by Persianate materials, like Qur’anic interpretations that are also stories with instructive lessons for readers.[7] There are several Persian Qur’anic exegetical works which resemble folk stories. Richard Winstedt suggested that “the work also appears to be from a Persian source: witness the use of the Persian form chawush for ‘courtier’”.[8] He referred to the work as “the Hikayat Yusuf or the Story of Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife”.[9]

I have examined hundreds of Persian and Arabic works to identify the origin of the text. Two short commentaries on the Qur’an (Q12) from the medieval Persianate world are the main prototypes of Dd.5.37.

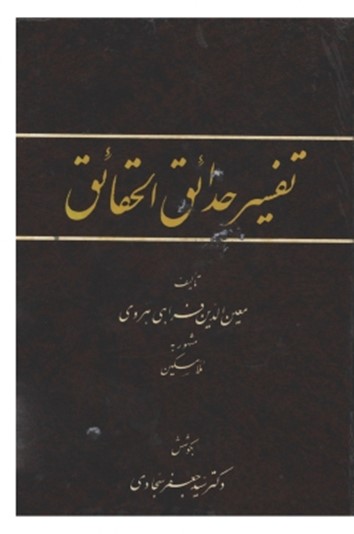

Our first Persian text that shapes the chief part of the Malay source is Tafsir-e Hada’iq al-Haqa’iq (Fig 3) by Mu‘in al-Din Farahi Heravi (d. circa 1501), from Herat in Afghanistan. As a mystic, he had authored further Qur’anic commentaries and Sufi treatises. His Tafsir-e Hada’iq al-Haqa’iq covers the story of Yusuf and Zulaykha based on Q12. Farahi Heravi relies on Arabic and Persian Biblical and Islamic literature mixed with his own reflections. He also alludes to the Persian poetry of ‘Abd al-Rahman Jami and some classical tafsirs. [10] The second tafsir with a smaller contribution is the Persian version of Bahr al-Mahabba fi Asrar al-Mawadda, widely ascribed to Imam Ahmad al-Ghazali (d. c. 520), who was a Sufi and traveller.[11] Recent studies have alternatively ascribed the work to al-Qushayri.[12]

Although a comprehensive analysis of the Persian-Malay texts will be the subject of my forthcoming study, I would like to draw attention to a few fragments to show some obvious similarities between Dd.5.37 and these Persian commentaries, mainly Farahi Heravi’s exegesis:

- The story of a person who prayed a lot to visit the Prophet Yusuf. He waited for Yusuf in the well that was already made by Shaddad b. ‘Ad. In the Persian version, the person’s name is “Hud” (هود), while in the Malay one it has been slightly changed to “Yahud” (یهود):

- Malay version, Dd.5.37, ff.7v-8r

کال سورڠ اورڠ مهاسوچ عملڽ مها صالح دعاڽ مها مستجاب کڤد الله عزوجل نام سید ایت »یهود» درڤد قوم «نبی یهود» علیه السلام. مک ایّ مماچ صحیفه ابراهیم علیه السّلام دالم قِصَّةُ الیُوسُفْ دبچاڽ مک سید ایت ایت برهی هندق برتمو دڠن یوسف علیه السلام مک ایّ مماچ دعا این مکین بپیڽ «اللَّهُمَّ رَبِّی اَساَلُكَ أَنْ تومَخرِفِی حَیَاتِی»[13] مک دعا سید ایت دڤـر کننکن الله عزوجا مک سید مڠر سوار دمکین بپیڽ هی یهود ڤـرڮ اڠـکو کڤد تلاڮ یڠ دکورق سلاد ابن عاد دیم اڠـکو دلم تلاڮ ایت نسچای یوسف علیه السلام داتڠ کڤـدام مک سید ایت فرڮ کڤد تلاڮ ایت مک سید ایت دیم دلم تلاڮ ایت میمبر الله تعالی برمول مکانن سید ایت بوه لیم دان قندیل سوات ترڮا نتڠ سواة تیاد برتا(…) دان تیاد برسمب دان تیاد بر میپق کلکین یوسف علیه السلام ڤـون دبوڠکن سکال سودراڽ کدالم تلاڮ ایت مک ستله سمڤی یوسف علیه السلام

- Persian version, Hada’iq al-Haqa’iq, Sajjadi Edition, p. 167

و در آن زمان مردي بود که به هود نبی ایمان آورده و وي نیز مسمّی به هود بود و در صحف شیث پیغمبر توصیف یوسف مذکور بود، و به مطالعه این مرد مسمی یهود رسیده بود، از بسیاري اشتیاق بملاقات یوسف دعا کرد، که «اللّهمّ انّی أسألک ان تؤخرنی و لا تقبض روحی حتّی ارنی یوسف». حق تعالی دعای وي اجابت فرمود، و هاتفی مر او را گفت ترا در چاه شداد بن عاد متوطن باید شد، تا بوقت رسیدن یوسف که موعد ملاقات وی با تو در آن چاه خواهد بود. هود آن چاه موعود را صومعه خود گردانید، هر روزي یک انار از باغستان عالم غیب از برای وی می فرستادند، و قندیلی از نور ملکوت برای وی برافروخته بودند، (…)

- The episode of Malik bin Za‘ar who saved Yusuf from the well which is found in Malay and Persian versions

- Malay Version, Dd.5.37, fol.13

مک مالک ابن دعر بر سڠڮره ممبوات ارتیڽ ڤد انتاڽ برجالن لبنو ادَامْشَقْ لاک کبنو کَنْعَانْ مک ستله داتڠ کبنو ایت مک مالك ابن دعر سکال ڠله کبوم سکال ڠله کلاڠت منت کنقکانق ایت مکی منڠر سوار دمکین بپیڽ هی مالک ابن دعر لاڮ لیم تاهن لاڮ انتارم دان انتار انقکانق ایت مک ستله ڮنّڤ لیم تاهم مک برجالن (…)

- Persian version, Hada’iq al-Haqa’iq, Sajjadi Edition, 190 (also Bahr al-Mahabba, Sajedi’s Translation, pp. 34-35)

پس مالک چون از معبّر این بشارت استماع نمود، در تهیه اسباب سفر درآمده عزیمت شام کرد چون به زمین کنعان رسید، در آن مقام فی الجمله توقف نموده، روي به آسمان آورد که قبله دعا است و گفت: وقت است اگر آنچه موعود است، بانجاز انجامد، هاتفی آواز داد که وفا نمودن بموعود بعد از گذشتن پنجاه سال دیگر میسّر خواهد شد، مالک از آنجا روان شد و هر سال بر سبیل اختیار میکرد و به زمین کنعان گذر میکرد، بطمع آنکه شاید چهره مقصود از تتق غیب جمال نماید.

One may also find further similarities in other episodes about the price paid for Yusuf as a slave in the market, and that his value was compared with gems and wealthy materials:

| Persian (p.218) | Malay (fol.25) | Translation |

| مشک | کستوری | Musk |

| عنبر | عنبر | Amber |

| کافور | کافور | Camphor |

| زر | امس | Gold |

| ابریشم|دبیقی | ستری | Silk| Fine garments |

Regarding Potiphar’s wife, Zulaykha, and her background, the Persian descriptions resemble that of the Malay commentary. In both Persian works she is “the daughter of a king in the West, whose father was Timus. There is a six-month[14] distance between their hometown and Egypt.”[15] The Malay version says: ada seorang puteri bernama Zalaykha (Zulaykha) anak raja benua Timus adapun jauh negara-nya itu (…) kiri enam bulan perjalanan (“There was a princess whose name was Zulaykha, the daughter of the King Timus. Their city is six months away from [Egypt]”) (fol.22).

The Persian episode of Yusuf and Benjamin when the former gave the latter a “red ruby” whose value is “five hundred dinars” (in Hada’iq al-Haqa’iq) or “fifty thousand dinars” (in Bahr al-Mahabba) is identical in the Malay version: “daripada manikam yang merah harganya lima puluh ribu dinar (…)” (fol.49r).

Further Persian terms and phrases like “وقت صبح” (“in the early morning”) fol.9; “گندم” (“wheat”) fol.36; “چوشڽ” (“his courtiers”) fol. 51; and other episodes about “Bashir”, “Khabbaz and Saqi”, “Jamilah” and “Rubil” are clearly found in the Malay manuscript Dd.5.37.

The number of verses from Q12 and their interpretations which form the main body of the work, direct translations from the two Persian commentaries as well as the existence of Persian words and phrases confirm that Dd.5.37 is a commentary on the Qur’an based on Persian prototypes.

- The Significance of the Manuscript

As I demonstrated above, Dd.5.37, copied in Aceh in 1604, is the earliest known dated Malay commentary on the Qur’an. Although its narrative acts like a folk story, its content and formation is directly taken from Persian commentaries. The Persian prototypes are among common Sufi works in the Persianate world, which made inroads to the Malay-Indonesian world from the 15th century onwards. The commentary of Hada’iq al-Haqa’iq, as the main prototype of Dd.5.37, was produced in the Great Khorasan, where other influential sources like Akhlaq-e Mohseni by Va’iz Kashifi were composed. Interestingly, the first known Malay translation of Kashifi’s work was also written in 16th-century Indonesia. It is now also a part of Erpenius’ library (MS Gg.6.40iii).

Dd.5.37, as a very old commentary, should be seen along with another old Malay commentary (Ii.6.45), which also belonged to Erpenius.[16] Considering the above-mentioned hypothesis that Erpenius was in the possession of his Malay sources before 1617, as well as the unicorn watermark of Ii.6.45 commonly used at the turn of the 17th century, Ii.6.45 represents the other significant surviving early classical Malay commentary.

Thus both Dd.5.37, dated October 1604, as well as Ii.6.45, written before 1617, belonged to Erpenius, were produced during the ascendancy of Sufism in Southeast Asia and are fundamental sources for the study of early Islam in the Malay-Indonesian world.

A new edition of Dd.5.37 with an English translation will be published in the near future.

[1] My thanks go to Peter G. Riddell and Edwin P. Wieringa for their helpful comments. All errors are mine.

[2] See, Ph S. van Ronkel, “Account of six Malay manuscripts of the Cambridge University Library,” Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde van Nederlandsch-Indië,1ste Afl (1896): 1-53

[3] Thomas Erpenius, Historia Josephi Patriarchæ, ex Alcorano, Arabice (Leiden: ex Typographia Erpeniana Linguarum Orientalium, 1617).

[4] Ibid, B2-C2 [it should be noted that these codes (A, B, C, D, E, etc.) were added by Erpenius to his manuscripts to be used in his printed volumes]

[5] For more, see: Vladimir Braginsky, The Heritage of Traditional Malay Literature (Leiden: KITLV Press, 2004).

[6] Edwin P. Wieringa, “The story of Yusuf and Indonesia’s Islamisation: a work of literature plus.” In: Islamisation: Comparative Perspectives from History, edited by A. C. S. Peacock (Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2017): 444-471 (especially 447-449).

[7] One may refer to commentaries of Va’iz Kashifi from the 15th and 16th centuries.

[8] Richard O. Winstedt, A history of classical Malay Literature (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1969), 87.

[9] Ibid.

[10] See Mu’in al-Din Farahi Heravi, Tafsir-e Hada’iq al-Haqa’iq. edited by Seyed Ja‘far Sajjadi, 2nd edn (Tehran: Tehran University Press, 1384/2005), 10-26.

[11] For a recent edition and translation see, Shaykh Ahmad al-Ghazali, Bahr al-Mahabba fi Asrar al-Mawaddah, trans. Afshin Sajedi (Tehran, n.d.) [online version].

[12] See Ali Navidi, Ahsan al-Qissan (Tehran: Bonayd Afshar, 2020).

[13] اللّهمّ انّی أسألک ان تؤخرنی و لا تقبض روحی حتّی ارنی یوسف

[14] In Sajedi’s translation, it is mentioned as “شش شهر”, literally “six cities” (68). Whether he did not translate the Arabic term “shahr” (month) is not clear. For another translation see, Ahmad al-Ghazali, Raz-o Nias, translated by Mohammad Musavi Khvansari (Qom: Markaz-e Matbu‘ati dar al-Tabligh Eslami, 1351/1972), 47.

[15] Bahr al-Mahabbah, 66.

[16] For a detailed analysis of the manuscript, see: Peter G. Riddell, Malay Court Religion, Culture and Language: Interpreting the Qurʾān in 17th Century Aceh (Leiden: Brill, 2017).