A cracking medical manuscript under the microscope

This post comes as part of our series from the Curious Cures in Cambridge Libraries project. Rachel Sawicki, Project Conservator, and Sarah Gilbert, Project Cataloguer, share their insights into a manuscript that once belonged to Henry VII and his wife, Elizabeth of York, and which has required delicate interventive treatment in order to conserve its illuminations…

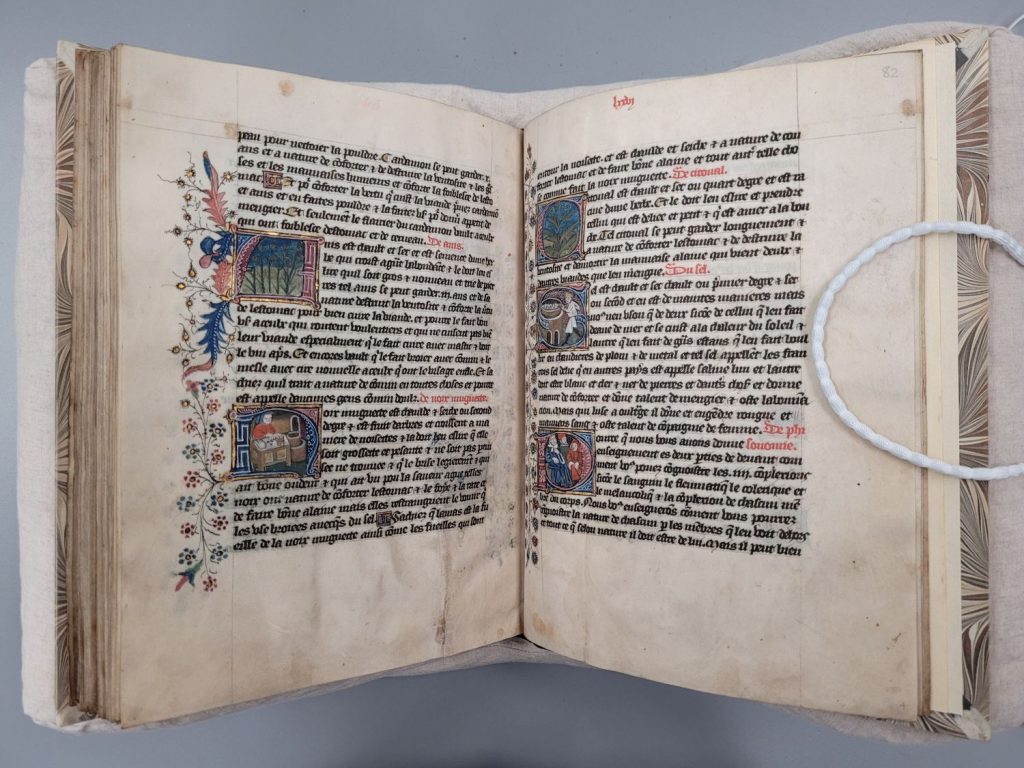

Everyone loves a cracking little medieval manuscript, except when the cracking refers to the media used in its text and illustrations. Among the 52 University Library manuscripts included in the Curious Cures project is MS Ii.5.11, a characterful (and character-filled) copy of a medieval guide to healthy living. It contains an abundance of naïve and charming vignettes throughout its superb parchment leaves. Painted – in M.R. James’s words – ‘in fair but not distinguished style’, these depict scenes of medieval life in all its glory and gruesomeness, making this manuscript a firm favourite of our Curious Cures project team. It is now available to view in full on the Cambridge Digital Library.

and (right) a ?zedoary plant, a man evaporating water to make salt, and three physicians conversing (MS Ii.5.11, ff. 81v-82r)

History

MS Ii.5.11 is a copy of the Régime du corps (‘A Regime for the body’), a medical work that was written in French in 1256 for Beatrice of Savoy, countess of Provence, by her physician, Aldobrandino of Siena. The Régime du corps is a guide to a healthy life and a good diet, rather than a medical textbook with a focus on diagnosing and treating illnesses. It is divided into short chapters, each with a different topic or focus that Aldobrandino selected and summarised from some of the most popular medical works of his time. The Régime du corps became very popular in the later middle ages: one of the first medical guides to be written in a vernacular language, it was quickly translated into other vernacular languages as it spread across western Europe.

This particular copy dates from the mid-15th century and was made in France, perhaps somewhere in or near Rouen. Although we do not know the name of the original owner, such a beautiful and luxuriously decorated book was probably destined for a reader among the upper echelons of society.

The manuscript did not remain in France for long, for within a few decades of its creation it passed into the collection of King Henry VII of England and his wife, Elizabeth of York. We do not know precisely how or when the manuscript came into their possession, but it was probably after 1486, when the two were married: after the table of contents, but before the beginning of the text, a bifolium was inserted and Henry and Elizabeth’s joint coat of arms was painted onto it (Henry’s are on the left half of the shield, Elizabeth’s on the right).

Conservation

When Curious Cures Project Conservators Rachel Sawicki and Marina Pelissari first assessed this manuscript, it was evident that it had always been a popular but well cared for little book. Signs of use, including handling dirt, had left some of the pages soiled, though generally the state of preservation is remarkable. The medieval binding is long gone, and the manuscript has been trimmed and rebound. The current binding is typical of those found on many UL manuscripts: it was made by Douglas Cockerell & Son in 1961 and features their characteristic marbled paper sides, a goatskin leather spine, and parchment corner tips on the boards.

Structurally the manuscript is stable, though the vividly painted miniatures, flourishes, and initials showed signs of flaking, cracking and loss. Manuscript inks and pigments deteriorate for a number of reasons: these can include improper preparation of the substrate, paint or binder; inherent vice within the chemistry of the colourant; mechanical stresses such as abrasion or flexing of the substrate; accidental damage; poor storage environments; high levels of usage; and the natural effects of ageing.

Using high powered stereo magnification, every miniature was checked for cracks and the presence of unstable pigments. A tiny 15x zero brush was used to gently test adhesion, and vulnerable paint layers were re-adhered by the delicate application of warm isinglass solution underneath the lifting flakes. Isinglass is derived from the swim bladder of sturgeon fish and has long been used by conservators due to its excellent working properties, strength and flexibility, unobtrusive optical properties, and stable long-term aging characteristics. It is a precious resource and is used in sustainable quantities in our studio.

The chance to examine this highly decorated manuscript in such fine detail has been a delight. The miniaturists used a joyful palette to achieve colours as bright as jewels, metals that shimmer across the page, and earthy muted tones that capture both the subtlety and splendour of the European medieval manuscript palette.

In addition to appreciating the colour palette, we also particularly enjoyed exploring how the miniaturists worked the media. The use of delicate paint layers to build up dimensionality in the figures’ faces is a lovely detail, as seen here in the rendering of the woman’s brow and nose bridge in this lovely vignette depicting a woman taking care of her face in order to maintain a ‘healthy glow’ (a ‘bonne couleur’ in the manuscript, see f. 43v).

Another personal favourite includes the working of metallic compounds in the background of this vignette of a person examining their teeth and gums (see f. 42v). Surface texture has been applied to help reflect and disperse light in this glittering scene.

You can now explore and enjoy the Regime du corps in its entirety on the Cambridge Digital Library.