Voices from SANAC

In partnership with the University of Cape Town and the Five Hundred Year Archive (FHYA) research initiative, Cambridge University Library has recently digitised Sir Godfrey Lagden’s five-volume presentation copy of the South African Native Affairs Commission (SANAC) 1905 report and minutes of evidence. High resolution images are available through Cambridge University Digital Library (CUDL) via the Southern African Collections project page. In addition, fully searchable PDFs are now available as an archival curation through FHYA’s digital platform, EMANDULO. Using this platform, users can add comments or further information and transcriptions or translations by creating a profile through the site and uploading relevant material.

In all, the commission considered evidence from 256 witnesses, not including those treated as groups. Around 65% of the witnesses were drawn from the Cape Colony and Natal. Many of the witnesses were well-known figures of their day, including William Carter, the second Bishop of Pretoria, Jules Ellenberger, later Resident Commissioner of Bechuanaland (Botswana) and William Beaumont, Supreme Court Judge in Natal. Equally, the commissioners considered evidence across a reasonably broad cross-section of southern African society. Thus, many interlocutors were described as farmers, traders, teachers, journalists and missionaries, as well as local community leaders referred to as ‘native chiefs’ or ‘native headsmen’ in the nomenclature of the early 20th century.

In this post we draw out some of the interlocutors, particularly highlighting African voices, to suggest some entry points to the SANAC volumes.

1. Martin Lutuli (d. 1921)

‘I think myself that it is time we had a voice in the Parliament’ (Vol. 3, p. 861)

Described as a ‘native farmer’, Lutuli [or Luthuli] was examined on 28th May 1904 at Durban. His testimony touched on his occupation of wagon making and farming activities on a piece of land near Tugela in what is now known as KwaZulu-Natal. In the 1880s he acted as secretary to the Zulu chief, Dinuzulu. The commissioners’ main interest, however, was in the Natal Native Congress, which Lutuli had founded with a group of others in 1900-1 to promote African interests, particularly political representation. In 1912 the congress affiliated with the South African Native National Congress, which became the African National Congress (the ANC), widely recognised as the oldest liberation movement in Africa. Lutuli’s nephew, Albert Luthuli, served as president of the ANC between 1952 and 1967.

2. John Tengo Jabavu (1859-1921)

‘Still do you not think that if a Native is educated higher than the standard he requires for the performance of his work, it would to a certain extent unfit him and discount his usefulness? – Not more than it unfits the European. Any educated man could turn his abilities to anything, and he would do so’ (Vol. 2, p. 726)

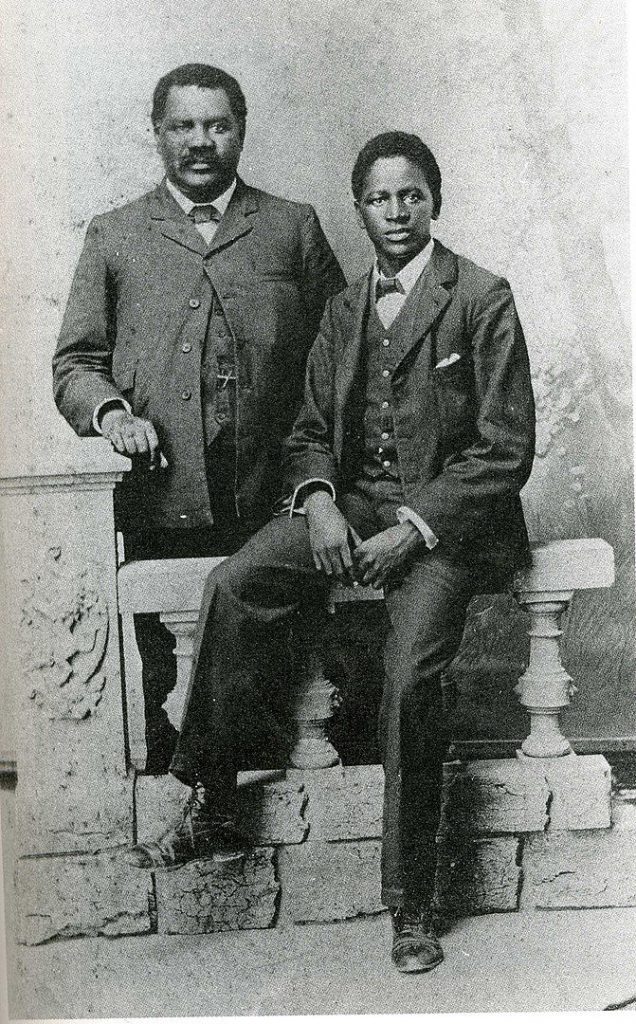

The Jabavu family were a prominent political and literary force in 20th century South Africa. John Tengo Jabavu was editor of the first newspaper written in isiXhosa, Isigidimi samaXhosa (The Xhosa Messenger), published at the Lovedale Press, and founded his own newspaper, Imvo Zabantsundu (Black Opinion) in 1884. His son, Davidson Don Tengo Jabavu (1885-1959), was the first African academic at the University of Fort Hare and his granddaughter, Helen Nontando ‘Noni’ Jabavu (1919-2008), had a long and successful literary career. Tengo Jabavu’s testimony to SANAC centred on the issue of land tenure and the Glen Grey legislation of 1894 which had compelled Xhosa men into employment by means of a labour tax.

A number of pamphlets authored by Davidson D.T. Jabavu have also been digitised and are available on the Southern African Collections project page.

John Tengo Jabavu, on the left, pictured with his son, Davidson Don Tengo Jabavu, c. 1903 ,from C. Higgs, ‘The Ghost of Equality’ (1997), p. 77. With an example of one of the digitised pamphlets.

3. Reverend Elijah Mdolomba (b. 1866)

‘I like the principle that a man should hold his own piece of land. We have seen in the history of the people of other nations that this is a good system’ (Vol. 2, p. 278)

Elijah Mdolomba was an ordained minister in the Wesleyan (Methodist) Church. He gave evidence to SANAC on behalf of a group representing the Ndabeni Location in the Cape Colony, now a suburb in the city of Cape Town, but originally an area of land set aside for African dock labourers. Mdolomba’s testimony again largely relates to the issue of land tenure and the various proposals for land ownership; some clergymen, like Mdolomba, while in favour of individual tenure, also supported the notion of ‘locations’, areas set aside for particular ethnic groups. In the period following SANAC, Mdolomba played an active role in the Cape African National Congress and served as Secretary-General of the ANC from 1930-6 under the presidency of Pixley Seme.

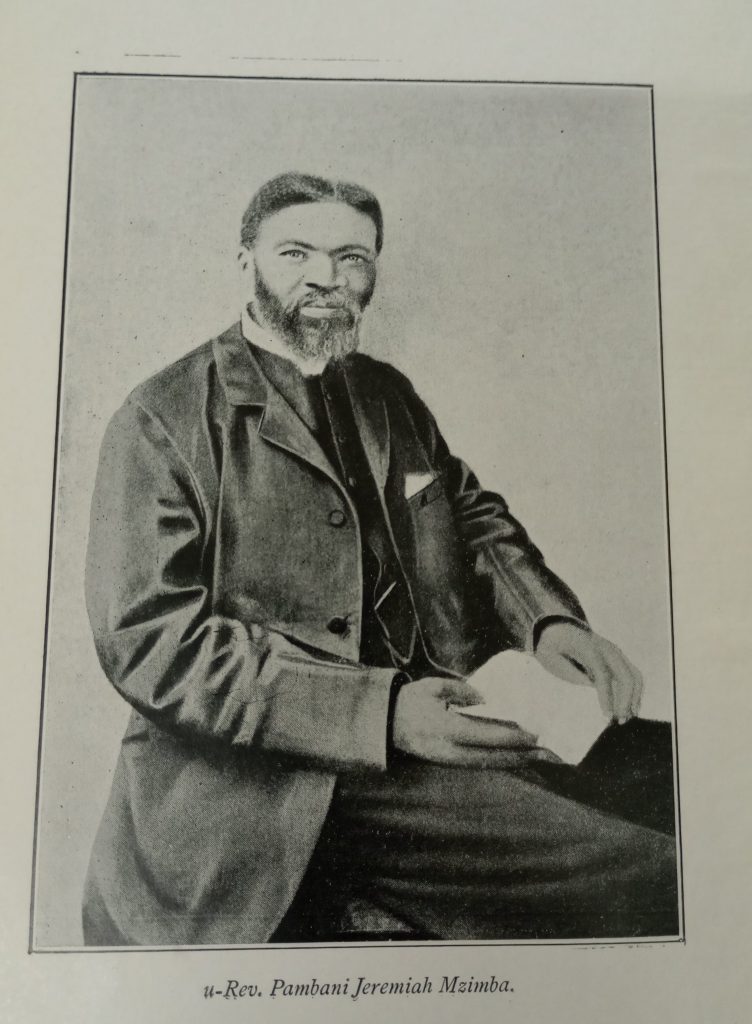

4. Reverend Pambani Jeremiah Mzimba (d. 1911)

‘My intention was simply to work independently, thinking that it might work better that way [on the decision to break away and establish the Presbyterian Church of Africa]’ (Vol. 2, p. 793)

Mzimba was educated at the Lovedale Institute in Alice in the Eastern Cape and was an ordained minister in the Free Church of Scotland, before founding the Presbyterian Church of Africa. Mzimba’s testimony centred on questions around the hierarchy and administration of the new church and, in particular, the stance the Presbyterian Church of Africa would take in regard to the position of the ‘native question’. It has been noted that many of the African interlocutors were missionary-educated. This fact is underscored by written evidence presented by Dr A.W. Roberts, a missionary of the Free Church of Scotland, in response to the question, ‘What becomes of those who pass through Lovedale?’ The annexure comprises a list of occupations of men educated at the Lovedale Institute up to 1896, including those ordained.

5. Reverend Edward Tsewu (1856-1931)

‘The Government should as little as possible interfere with Church people, because they are sure to make a mistake and pull up a good tree and push it outside’ (Vol. 4, p.793)

The son of a deacon of the Lovedale congregation of the Free Church of Scotland, Edward Tsewu was born in Grahamstown in 1856 and was a Minister of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Together with Jeremiah Mzimba, Tsewu was embroiled in disputes over the direction and structure of the broader Presbyterian Church in South Africa. Tsewu was a significant leader in the struggle for land rights in South Africa in the early twentieth century, establishing the Transvaal Landowners’ Association. In his testimony to SANAC, Tsewu was adamant about his right to buy land and to register it in his own name, prompting a subsequent case before the Supreme Court.

6. Father Marc Barthélemy SJ (1857-1913)

‘Are you carrying on Mission work? – Personally, I have never been with the Natives; I have been always employed among the Colonists, and engaged in white work. I have no personal knowledge of the Natives, still, of course, I have been 18 years in South Africa, and I know indirectly, I think, a good deal about the Natives’ (Vol. 4, p. 192)

A French Jesuit priest, Fr Barthélemy, was a member of the Zambesi Mission, an endeavour by the Society of Jesus to evangelise in southern Africa. In 1896, he founded the boys’ school in Bulawayo, which went on to become St George’s College and later relocated to Salisbury (Harare), and was the first rector of the school. Although ostensibly a missionary, Fr Barthélemy’s experience was largely confined to interactions with the settler society in Bulawayo.

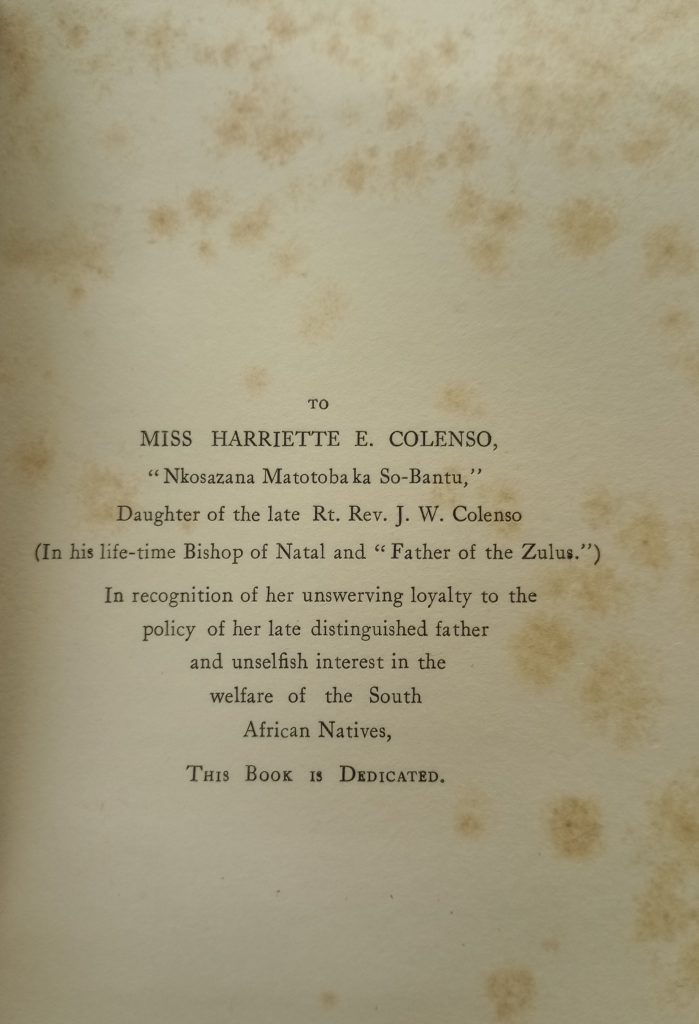

7. Harriette Emily Colenso (1847-1932)

‘I am not quite sure what you mean by tribal tenure, but my understanding of the communal tenure of land, according to their own ideas is, to quote their own saying, “Can land be bought?” – which is equivalent to saying it cannot be bought. It is a common thing which you cannot buy, any more than you can buy air. Everybody living must touch the land somehow’ (Vol. 3, p. 401)

‘As a woman, I do not think our system is wholesome or good’ (Vol. 3, p. 405)

The eldest daughter of John Colenso, the first bishop of Natal, Harriette Colenso was a British Christian missionary, who continued her father’s work, negotiating on behalf of the Zulu people to the British government. She worked as secretary to her father during the trial of Langalibalele, wherein he was defending the accused. She had a longstanding relationship with Zulu king Dinuzulu kaCetshwayo, serving as both advisor and advocate for him. During her lifetime, she worked to further her father’s goals for Natal, specifically, the continuation of the Church of England in Natal, and defending the rights of the native population of Natal and Zululand. In childhood she was nicknamed ‘Udhlwedhlwe’, a Zulu word meaning ‘walking stick’, signifying Harriette’s role as support and guide to her father.

8. Theophilus Shepstone (1817-1893)

‘Our views are these, that we decidedly object to any titles to land. We consider that the land tenure should be the same as it was under the old Government, in other words that all land held for Natives should be held by the Government in trust, or rather by the Native Commissioner’ (Vol. 4, p. 525)

Theophilus Shepstone was an English-born statesman who played a prominent role in the shaping of British native policy in the colony of Natal during his time as Secretary for Native Affairs between 1845 and 1877. Shepstone generally favoured the separation of settlers from Africans and sought to govern the populations separately with population-specific laws. In 1861, he visited the Zulu Kingdom and obtained a public recognition from Mpande kaSenzangakhona of Cetshwayo kaMpande as his successor. He officiated at the controversial coronation of Cetshwayo as king in 1873. He was also responsible for the annexation of the Transvaal to Britain in 1877.

9. Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje (1876-1932)

‘What is your object in carrying on this paper? – Supplying information to my people. […] What is your object in doing that; do you want to enlighten them? – Yes; that is my wish, if I can’ (Vol. 4, p. 264)

Sol Plaatje was 27 years old when he appeared before SANAC in September 1904 at Mafeking [Mahikeng], then the capital of the Bechuanaland Protectorate (Botswana). Plaatje is recognised as the first black South African to write a novel in English, Mhudi, published in 1930 but first written in 1919. As a journalist, described as a ‘native editor’ in his SANAC testimony, Plaatje edited the Setswana-English weekly newspaper Kuranta ya Becoana (Bechuana Gazette) and was involved in the running of a number of other vernacular newspapers. He is also known for translating some of the major works of William Shakespeare into Tswana.

10. James Stuart (1868-1942)

‘I think that the European people are apt to misconstrue the way in which these people governed their own people. Things that they did which appear to us arbitrary and cruel, were not necessarily so. It was a system that they fully understood and many of these practices which we mark down as being contrary to civilised usages, were just in themselves; it was justice’ (Vol. 2, p. 952)

James Stuart was a colonial official and a prolific recorder of oral historical materials in Natal in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In 1888, he was appointed clerk to the resident magistrate in Eshowe in the recently annexed British colony of Zululand, became a magistrate in the colony in 1895, and subsequently served as acting magistrate in a number of centres in Natal. In 1901 he was appointed as assistant magistrate in Durban. In the Natal rebellion of 1906, Stuart served in the Natal Field Artillery and in the intelligence service of the colonial forces. In 1909 he was appointed Assistant Secretary for Native Affairs in the colony’s Native Affairs Department. After the formation of the Union of South Africa in 1910, he was transferred to Pretoria. He took early retirement in 1912, and returned to Natal. The following year he published A History of the Zulu Rebellion, 1906, which remained the standard work on the subject until the 1960s.

In the late 1890s Stuart began devoting much of his spare time to interviewing people – particularly elderly African men – with a knowledge of the history of African societies in Natal (into which Zululand was incorporated in 1897), and, to a lesser extent, in Swaziland. At the same time, he read widely into the history of Natal. His aim was to make himself the leading authority on what he called ‘Zulu’ history and custom, with the wider purpose of being able to inform the making of native policy in the colony, which he saw as based on ignorance and misunderstanding of the historical Zulu system of governance.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

To submit contributions to the Voices of SANAC, please contact: rcs@lib.cam.ac.uk.

Further information on this project, generously funded by Carnegie Corporation of New York, is available on the project page: Creating new connections: shared digital curation of the Royal Commonwealth Society (RCS) southern African collections at Cambridge University Library.

Sally Kent, RCS Curator, & Chloe Rushovich, Engagement and Communities Officer