A Scientific Life: New additions from the Darwin Archive to Cambridge Digital Library

Post by Elizabeth L. Smith (Digital Curator, Nineteenth-Century Science Collections)

This autumn marks the completion of a four year project digitising the Darwin Archive, the working and personal papers of the naturalist Charles Darwin. By the end, more than 69,000 images will be available on Cambridge Digital Library, representing 75% of the classes in the Archive now available as high resolution images online to browse or download, including manuscripts documenting his life and research that were not previously available online. Any letters sent to or from Darwin directly are supplemented by transcriptions produced by the Darwin Correspondence Project which completed its work at the end of 2022.

Charles Darwin (1809-1882) graduated from the University of Cambridge in 1831, when he was recommended by the Professor of Botany John Stevens Henslow for a voyage around the world on the HMS Beagle. Following the journey he moved out to the village of Down in Kent, where he spent the next forty years developing his theories of natural and sexual selection based on his own experimental evidence and information sent to him by a network of correspondence with people around the world. In addition to his well-known evolutionary theories, he came up with important discoveries about coral islands, insectivorous plants, and earthworms.

Darwin’s work spanned numerous areas of interest, across botany, geology, and human anatomy. In addition to the notes Darwin kept on these subjects in notebooks, which held his thoughts and more theoretical musings, Darwin kept portfolios of evidence that he compiled to work on particular subjects or prepare to write his many publications. Enclosed in letters, Darwin was sent photographs, plant specimens, butterfly wings, and even human beard hair. It is now possible to view these specimens in high resolution. One such specimen is a packet of dried Benghal dayflower, sent to Darwin from William Turner Thiselton-Dyer, Assistant Director at the Royal Botanic Garden at Kew (DAR 178: 104). Thiselton-Dyer, who wrote that he had received the specimen from the Saharanput Botanical Gardens in India, knew that Darwin was interested in plants whose seeds developed underground. The specimen and the exchange around it demonstrate one way Darwin made use of colonial networks for evidence in his studies. He also received insect specimens, such as four naturalised bees still stuck to a letter that was sent to him by a plant nurseryman who was living in Christchurch, New Zealand, to whom Darwin had written for information about the fertilisation of clover (DAR 177: 323).

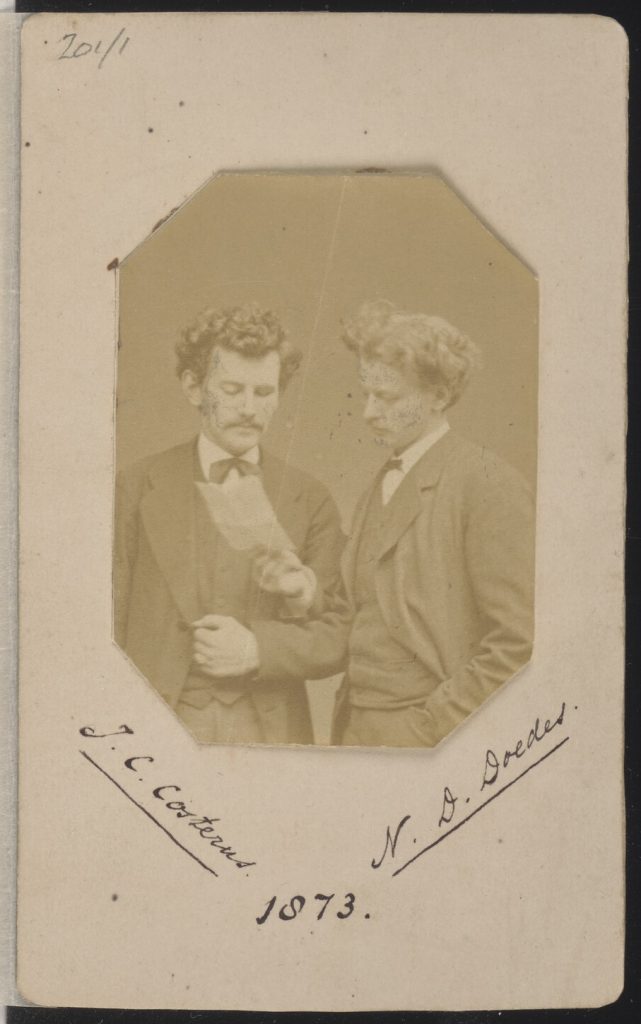

Darwin was also an enthusiast for the then-new technology of photography, and collected numerous photographs still available in the archive. His fascination with how humans express emotions caused him to collect numerous commercial photographs of children smiling, crying, and shouting, while his participation in scientific circles resulted in a collection of cartes de visite from many of his correspondents. One especially charming example was sent to him by some Dutch students who had written to him, then later sent him a portrait of themselves reading the letter Darwin had sent them in return (DAR 162: 201/1).

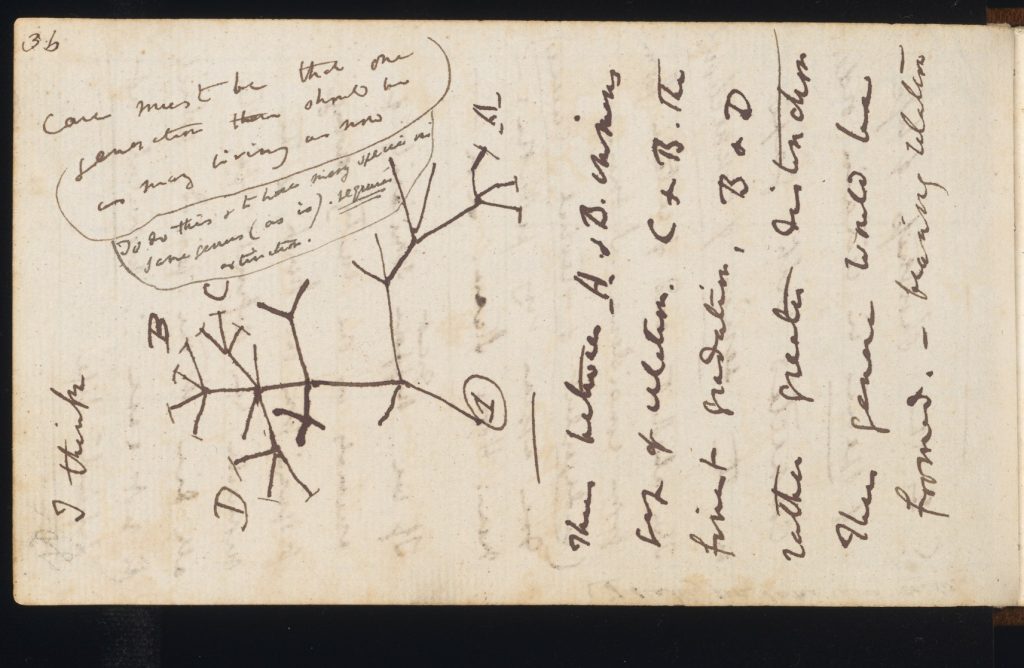

It is also possible to view the transmutation notebooks B and C (MS DAR 121 and 122), famously returned to Cambridge University Library in 2022. In addition to the well-known tree of life diagram, the notebooks show Darwin’s thinking between 1837 and 1838, as he worked through his observations on geographical distribution of species and affinities between extinct and currently existing animals in South America. They are part of a series of notebooks, allowing us to read Darwin’s developing thoughts on species development. Wonderfully though, we can read these thoughts in the context of the rest of his life – at the same time as he was coming up with the theories he would eventually publish in the Origin of Species, he was also preparing for his wedding to his cousin Emma Wedgwood, exchanging long letters as he prepared the house in London they would live in during the first years of their marriage (DAR 204: 151-157). The archive reflects the fullness of a long scientific life in a busy family home, both the domestic and the intellectual more than ever available to readers.