Thomas Richard Brown (1791-1875): poet, clergyman & collector

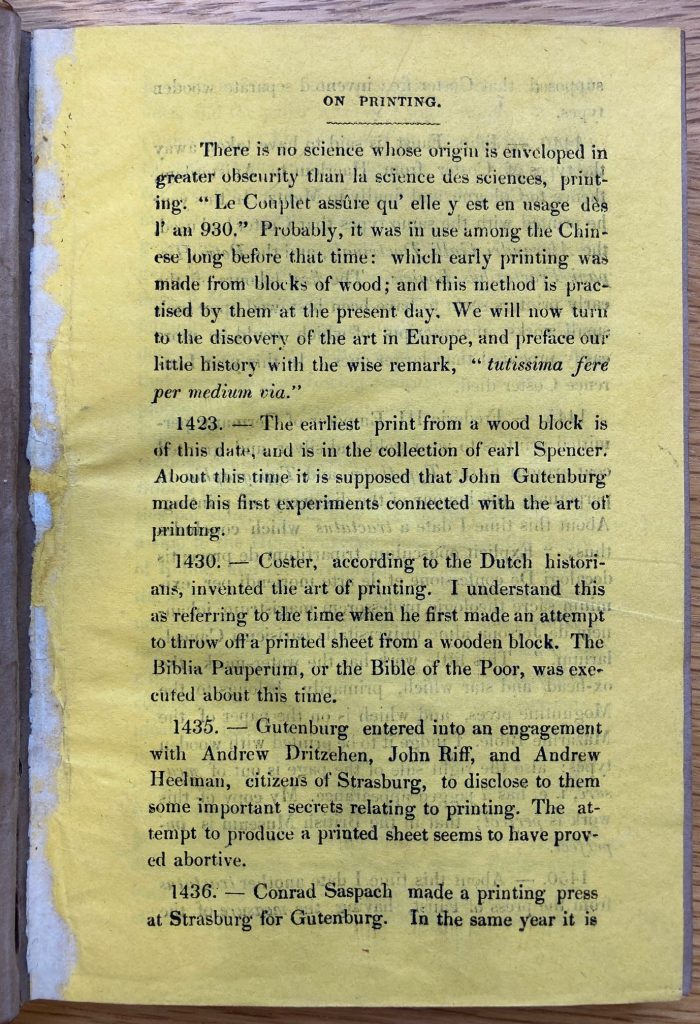

In October the Library hosted a conference to mark the centenary of the death of Francis Jenkinson, University Librarian 1889-1923, which included a display of books relating to his interests. One of these was the early Cologne printer Ulrich Zel and in two of Zel’s books (printed in Cologne in the 1460s) I spotted the small typographical book-label of one Rev. T. R. Brown at the Vicarage in Southwick (in Northamptonshire). It is not especially surprising to find a nineteenth-century clergyman collecting early printed books. But what makes Brown all the more interesting is that he appears to have operated his own printing press, with which he printed his own bookplates, several pages of notes on the history of printing (bound into one of his Zel books now at the University Library) and several other more substantial works on language and grammar. Through copies of these in the University Library and a few other sources, I have been able to bring together a fuller life story than that recorded in Venn’s Alumni Cantabrigienses.

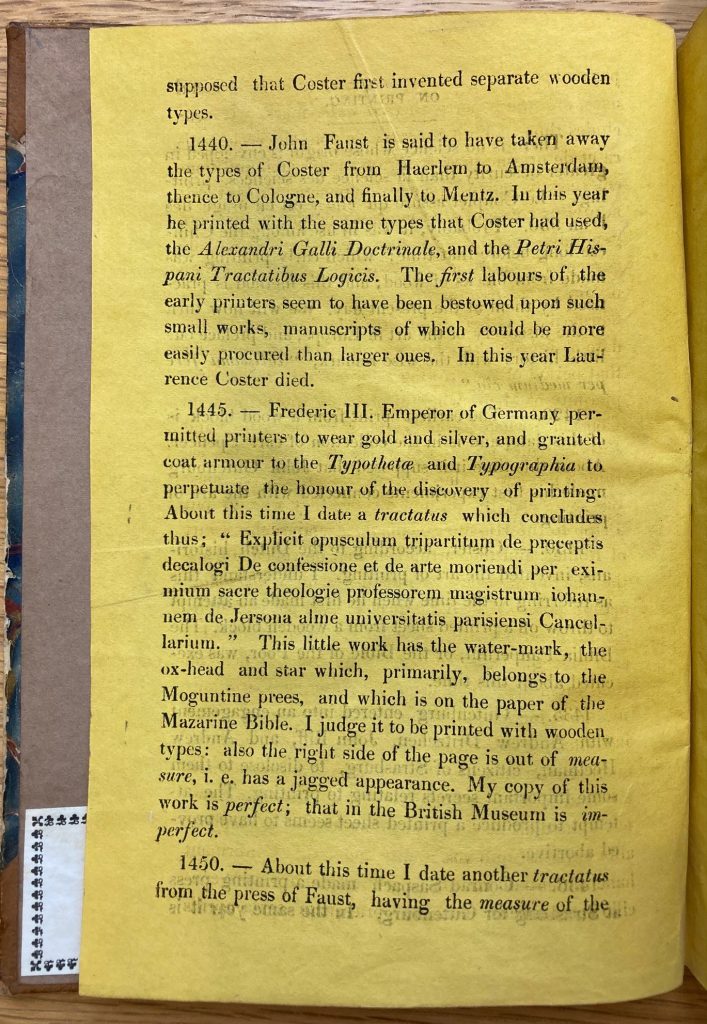

He was born in 1791 at Whatton (Nottinghamshire) and arrived in Cambridge at Easter 1810, matriculating at St John’s College Cambridge. He took his BA degree in 1815 and later that year was ordained, becoming curate at the church of St Michael & All Angels at Abington Piggotts (just north of Royston and about 15 miles south west of Cambridge). In 1834 he became Vicar of St Mary’s church in Southwick (between Corby & Peterborough, and about 40 miles north west of Cambridge). There he remained for forty years, until his death in September 1875. Brown’s library may have been substantial but few traces of it have come down to us. The six-page summary of the history of printing which he bound into one of his Zel books suggests that Brown was not just collecting without discernment and following the herd, but that he was engaged with ongoing discussions in the early nineteenth century around the story of the growth of printing in the west. He seems to have been especially interested in a subject which occupied much of Jenkinson’s time and provided the subject for his 1908 Sandars lecture: the order in which Ulrich Zel’s undated books were actually produced. Brown’s six-page history reproduces some standard elements of the history of printing, but weaves in information about his own collection.

Of an edition of the works of Jean Gerson he discusses the paper and its watermark (comparing it to paper used by Gutenberg) and notes that he thinks it was printed with wooden type, before recording triumphantly ‘My copy of this work is perfect; that in the British Museum is imperfect.’ He speaks also of Gutenberg’s Bible of c. 1455, apparently of the Mazarine copy in Paris, and notes that ‘the illuminated letters seem to be made by the same hand as my work of Jerson which I have dated 1445’ (presumably his perfect copy of Gerson discussed above), though he was of course mistaken about the date. He speaks of three more works by Zel in his possession – Cicero’s Amicitia, Paradoxa and Epitaphia – noting that ‘they are printed with the same type as the Officia, but are lined.’

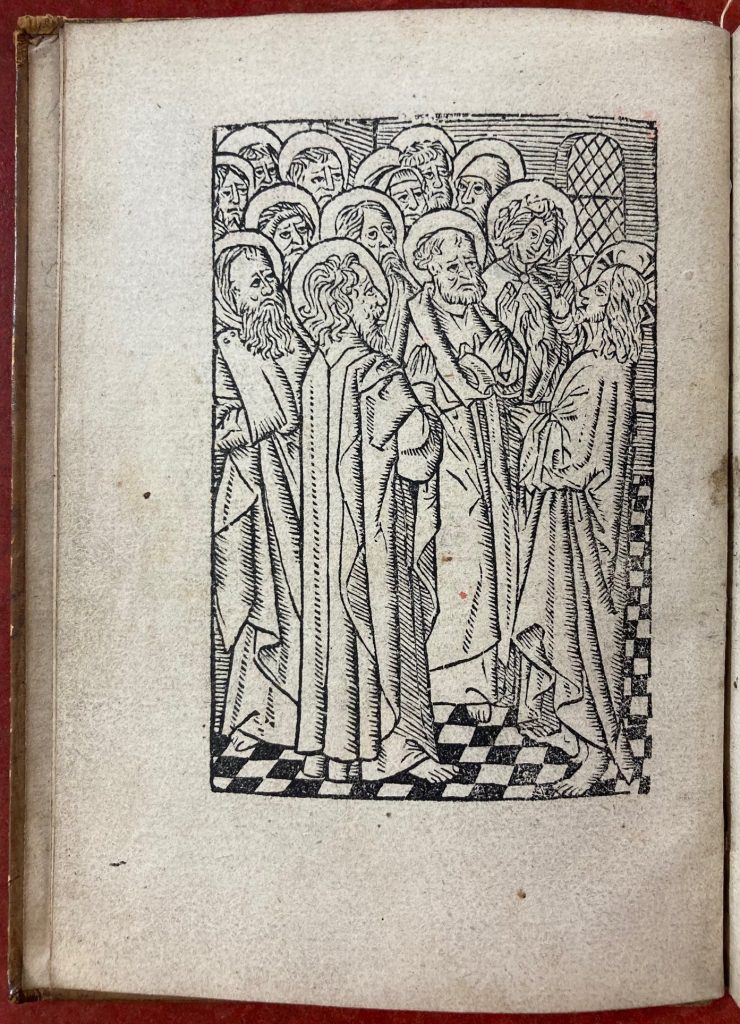

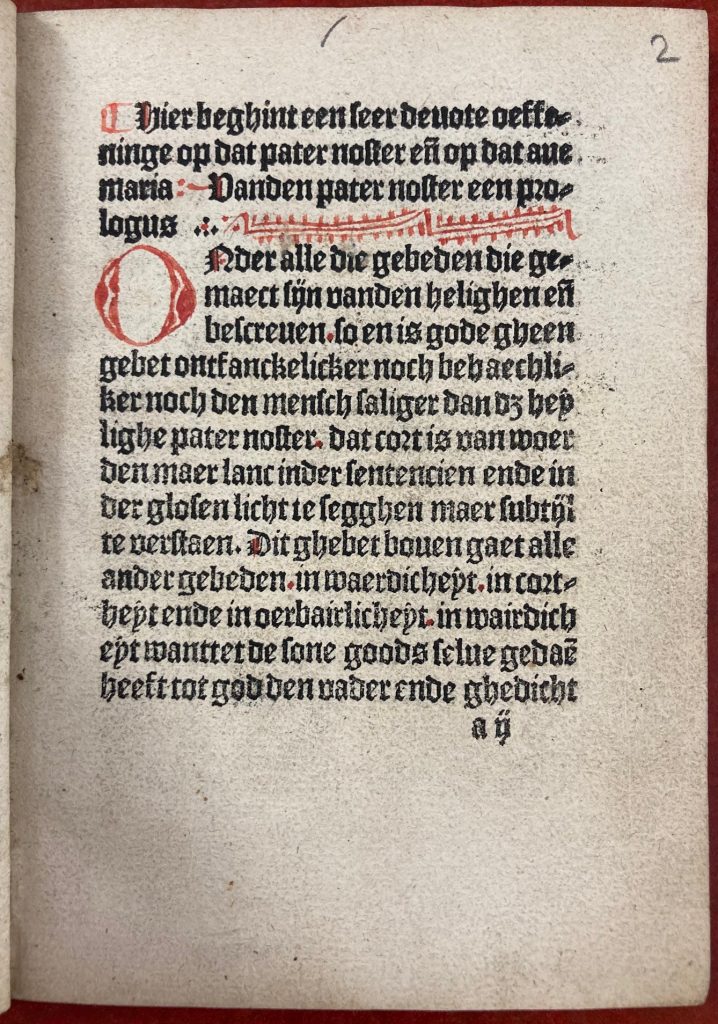

In addition to the two Zel incunabula now at Cambridge University Library (Cicero’s De officiis, c. 1465, later owned by Jenkinson, and a slim volume by Jean Gerson, c. 1466, separate I think from that mentioned above), I have found two other early books once in his possession which survive: a Haarlem-printed devotional book of the 1480s (also in the University Library, via our Victorian Librarian Henry Bradshaw: see images below) and a copy of the Constitutiones of Pope Clement V (Strassburg, Heinrich Eggestein, 1471), now in the British Library. No sale of Brown’s library is recorded in the usual places (including the List of catalogues of English book sales, 1676-1900, now in the British Museum, published in 1915) and his library may have been sold locally rather than in London. Certainly other books once in his possession, bearing his unassuming library labels, are likely to be lurking unknown in libraries, and I would be interested to hear of others, especially incunabula.

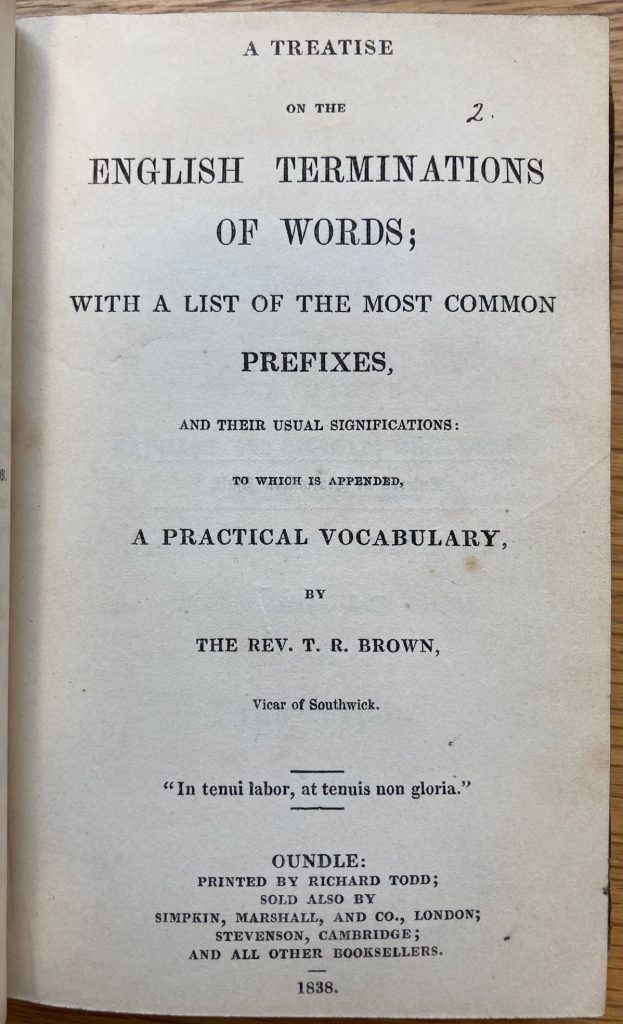

Brown’s legacy is far more visible in his works of grammar and etymology. His first seems to be a slim Treatise on the English terminations of words with a list of the most common prefixes, printed at Oundle (the nearest town to Southwick) in 1838. Its dedication, to two local ladies, says something of his social connections: ‘Dedicated to the Misses Katharine, and Henrietta Wheelwright, of Tansor, Northamptonshire; in token of the friendship & esteem entertained for them, by the author.’ Katharine Wheelwright (later Saunders), 1824-1901, went on to become a botanical illustrator, spending time abroad in Europe before moving to South Africa in the 1850s. She sent many natural specimens to Kew. Her father was the Rector of Tansor and therefore one of Brown’s nearest colleagues, Tansor being some four miles south east of Southwick.

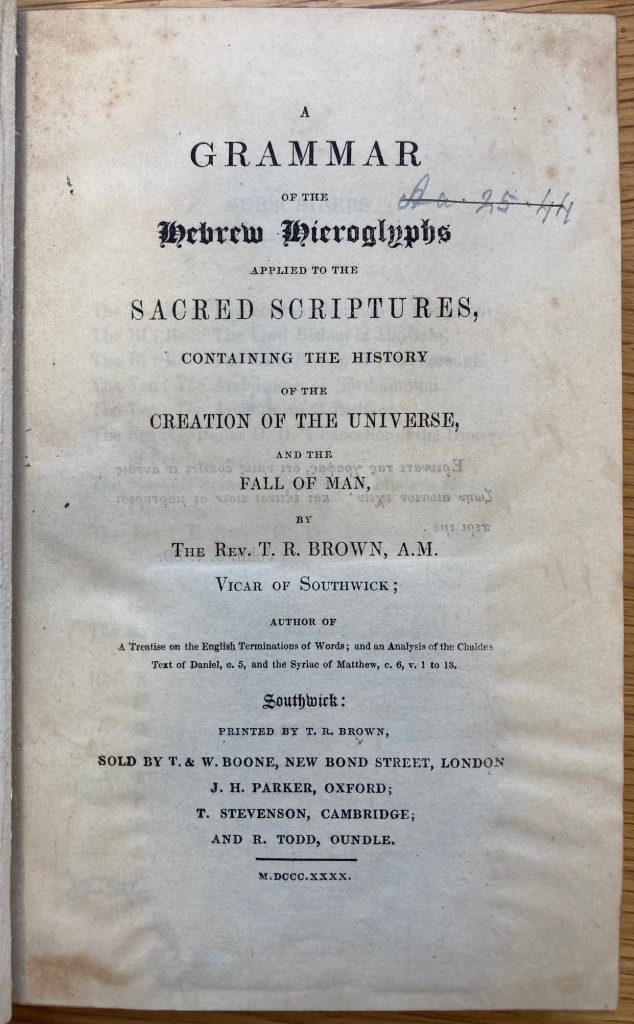

By 1840 Brown was printing his own books, producing A grammar of the Hebrew hieroglyphs applied to the sacred Scriptures in that year (236 pages). Brown had a number of prominent booksellers retail his book, including T. & W. Boone in New Bond Street (London), J. H. Parker in Oxford, T. Stevenson in Cambridge and R. Todd in Oundle. A short but impressive subscribers’ list reveals more of Smith’s social network, including the Archbishop of Canterbury (William Howley), the Bishops of Durham and Peterborough, and a number of local clergy (including the Rector of Tansor). In a brief introduction to his readers, Smith points out that ‘time will considerably improve my system’ and apologises for its general appearance: ‘the whole of the manual labour has been performed by myself; and that a considerable part of the mental composition is coeval with it.’ He was not, therefore, simply employing a printer but doing much of the manual work associated with printing himself.

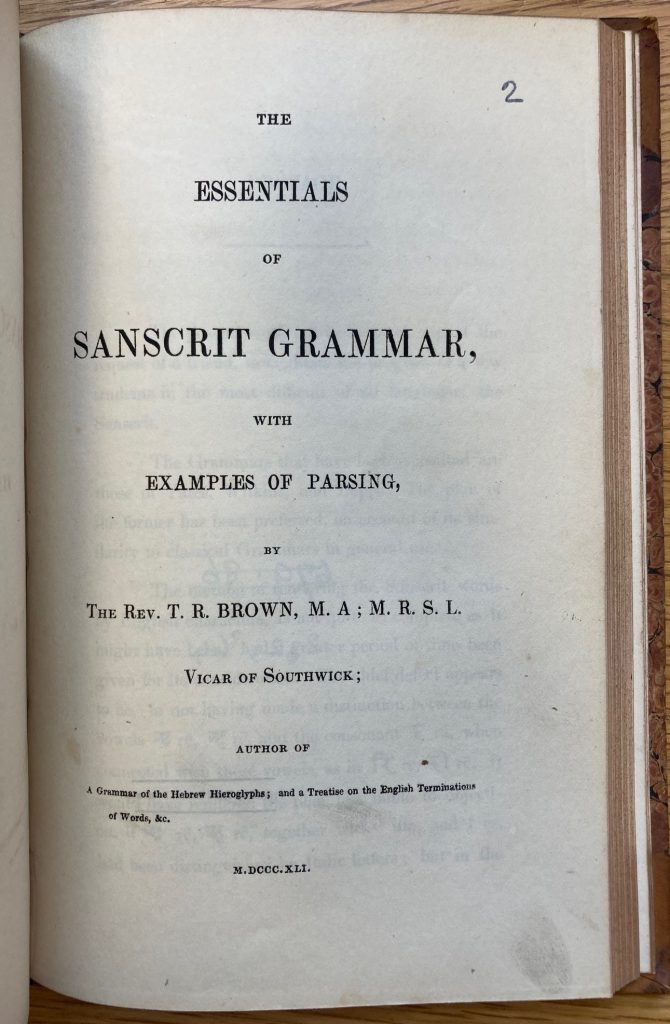

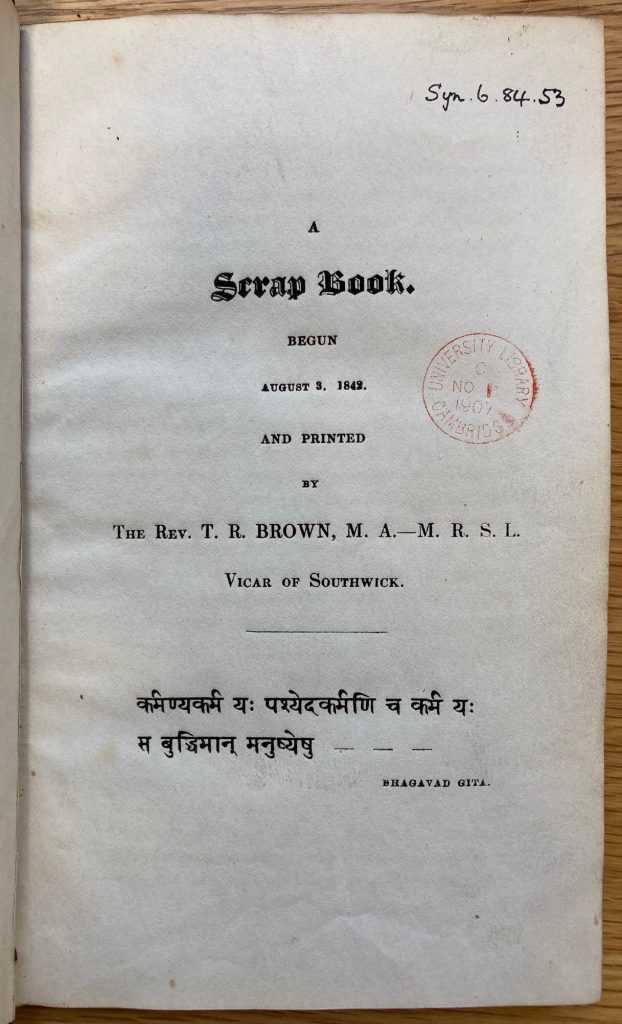

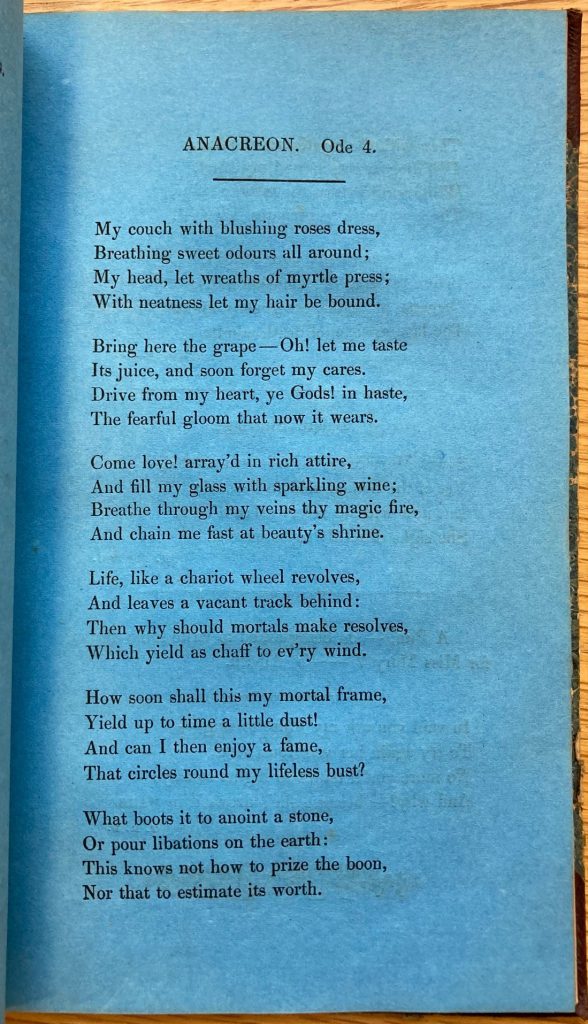

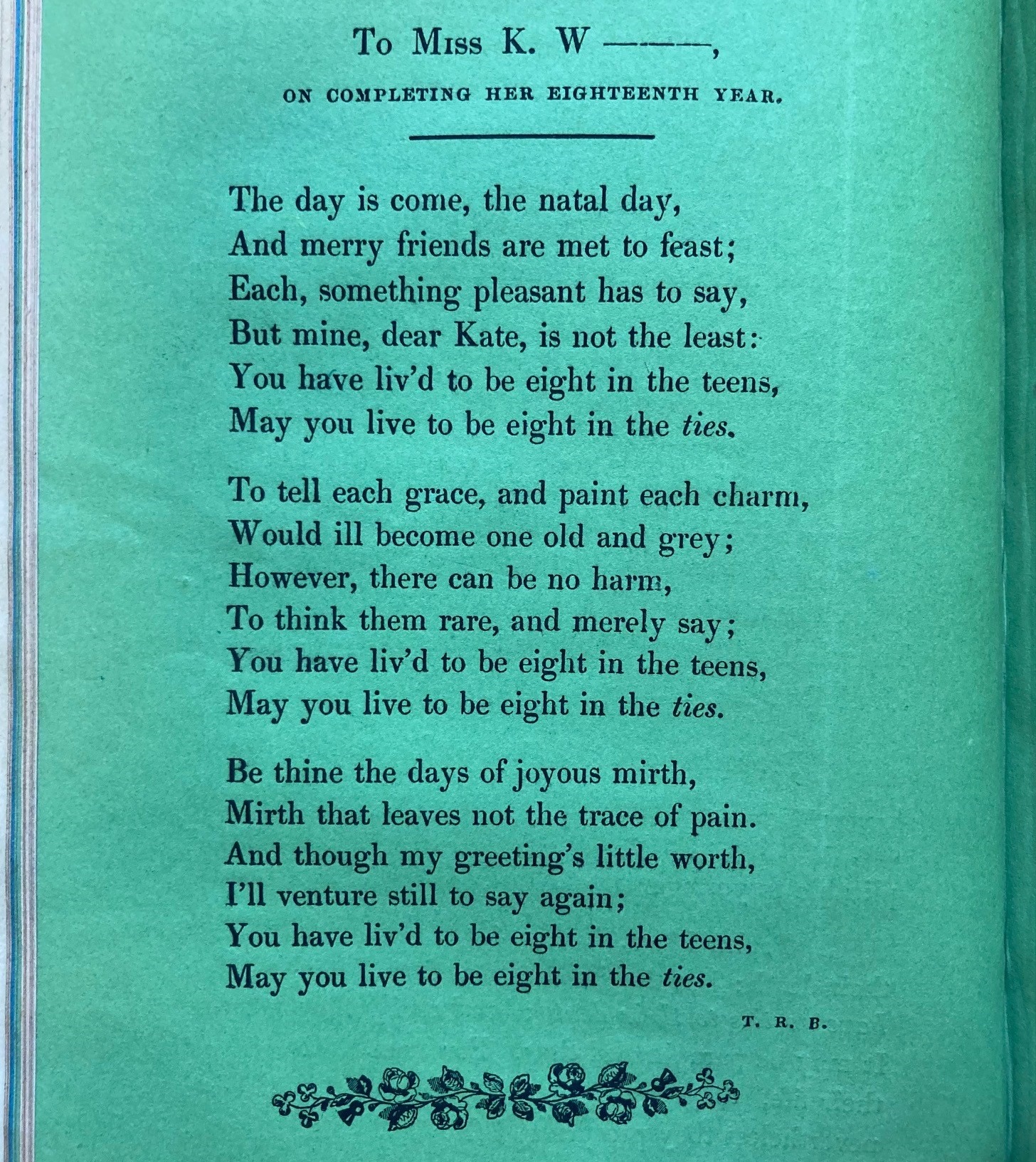

In 1841 appeared The essentials of Sanscrit grammar (140 pages long), but two more books, in various ways impressive achievements, are in many ways more interesting, apparently the last two to issue from Brown’s press. One was a two-volume Dictionary containing English words of difficult etymology (1843), totalling just over 500 pages, of which Brown produced just nine copies. Of this I have not seen a copy, but one is held at St John’s College, Cambridge, which bears no copy-specific marks of interest (with thanks to Dr Adam Crothers of St John’s College Library for having a look on my behalf). The last is a strange volume, entitled A scrap book: Begun August 3, 1842 and printed by the T. R. Brown (Southwick, 1847) This is a collection of poems, either by Brown or translated by him, alongside learned texts on various topics relating to ancient literature and languages. The book, of which only three copies were produced (ours being the only one which seems to survive) was printed on a variety of coloured papers, including blue, purple and green. Our copy, acquired from the London bookseller Bull & Auvache in 1907, has been annotated by Smith, with some corrections and additions. The poems range broadly, from juvenile compositions, including one written ‘on a water party … at the request of a lady’, from Smith’s Cambridge days in 1815 (presumably the summer in which he took his degree):

From the fam’d Fort St. George how she scuds it away

While the silver tip’d waves on her sides lightly play

She’s mann’d by three sailors well noted for skill

Who can cleverly steer her wherever they will.

Several verses to the Misses Wheelwright are included, one to ‘Miss K. W. on completing her eighteenth year’:

And though my greeting’s little worth

I’ll venture still to say again

You have liv’d to be eight in the teens

May you live to be eight in the ties.’

And one to Henrietta (clearly known as ‘Hennie’), on completing her seventeenth year:

The lily now with bosom fair

Sheds its rich perfume on the air

But Hennie is the lily rare

Whose praises I will sing.

A four-line verse entitled ‘Before Marriage’ hints at a potential match between Brown and one ‘Mary’, though this seems not to have come to fruition:

Sweet Mary long, ‘tis true was toasted

Yet of the honour seldom boasted

But now without reserve she’ll own

She sighs devoutly to be Brown!

The poems are not, by any stretch of the imagination, masterpieces. But alongside his linguistic work and his interests in the earliest products of the western printing press, they show the range of Brown’s intellectual interests. The few books which can be traced from his library hint at an impressive collection, brought together with a curious mind but sadly long since dispersed.

Munich BSB somehow has Brown’s copy of Gerson, Opus tripartitum (Marienthal, 1474): https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/en/view/bsb11303579?page=2,3

Ah interesting – thank you Eric. I’d love to find some records of the sale of his library but as yet haven’t had any luck. [Liam Sims, Rare Books Specialist].

Would it be possible to see the other pages of the pamphlet ‘On printing’? Thanks

Absolutely. I’ll send them along in an email. Liam.